The 3rd Basel Dementia Forum focused on various aspects of dementia in an interactive format. This provided important information for primary care physicians as well as interesting insights into a wide variety of positions and difficulties that can arise in the environment of those with the disease.

The opening lecture was given by Prof. Dr. phil. Andreas U. Monsch of the University Center for Geriatric Medicine at Felix Platter Hospital in Basel. He brought the assembled physicians up to date on the latest in dementia diagnostics. There are many difficulties here, mainly because the disease is gradual and, for example, people with higher memory capacity may have a higher cognitive reserve, through which the disease can be compensated for longer than is the case with patients whose memory is less trained.

Prof. Monsch presented the new Manuel DSM-5, in which the diagnosis of dementia now appears under the bracket of “neurocognitive disorders”. Only a mild and severe form are distinguished here, regardless of what caused the disorder [1]. Basically, the structure has been changed considerably: “First we ask whether the patient has a neurocognitive disorder, then we ask about the cause of this disorder,” says Prof. Monsch.

“Whether the distinction between the mild and severe forms is a happy one remains to be seen, but it is very positive to note that six different cognitive domains are distinguished, which are important in the medical examination and provide a good guide for the examiner.” These are, in detail:

- The complex attention

- The executive functions

- The learning and the memory

- The language

- Visuoconstructive-perceptual skills and

- Social cognition.

Clarification and screening in the family practice

It is essential for the general practitioner to proceed in a two-stage assessment after the patient himself and/or the relatives report the brain disorders: Stage 1 includes a general practitioner’s examination with medical history and dementia screening; the second stage provides for referral to a memory clinic or specialist, where a definitive diagnosis is made and specific treatment suggestions are developed [2].

A new screening tool is “BrainCheck”, which was presented at this year’s AAIC (Alszeimer’s Association International Conference) [3]. “This is a very useful, uncomplicated and, above all, valid instrument that is extremely helpful in the daily routine of family doctors,” is Prof. Monsch’s positive verdict. Specifically, the BrainCheck includes three questions for the patient, the clock test with the patient, and a questionnaire for family members. The three questions to the patient will clarify whether his ability to remember new things has decreased recently; whether relatives/friends have made comments that his memory has deteriorated; and whether the patient is affected by memory or concentration difficulties in everyday life. The interview of the relatives includes seven questions of the IQCODE [4] and elicits an assessment of the relatives about the patient’s condition today compared to two years ago. “The results of the BrainCheck tool on sensitivity (97%), specificity (82%) and discriminatory power (89%) are also very convincing,” said Prof. Monsch. The concept offers another plus for the practice: BrainCheck is available as an APP via iTunes for CHF 11, or Vifor’s field service. This APP guides the physician easily and safely through the various screening steps and follows an algorithm that can reliably detect cognitive disorders correctly.

What’s new in Alzheimer’s therapeutics?

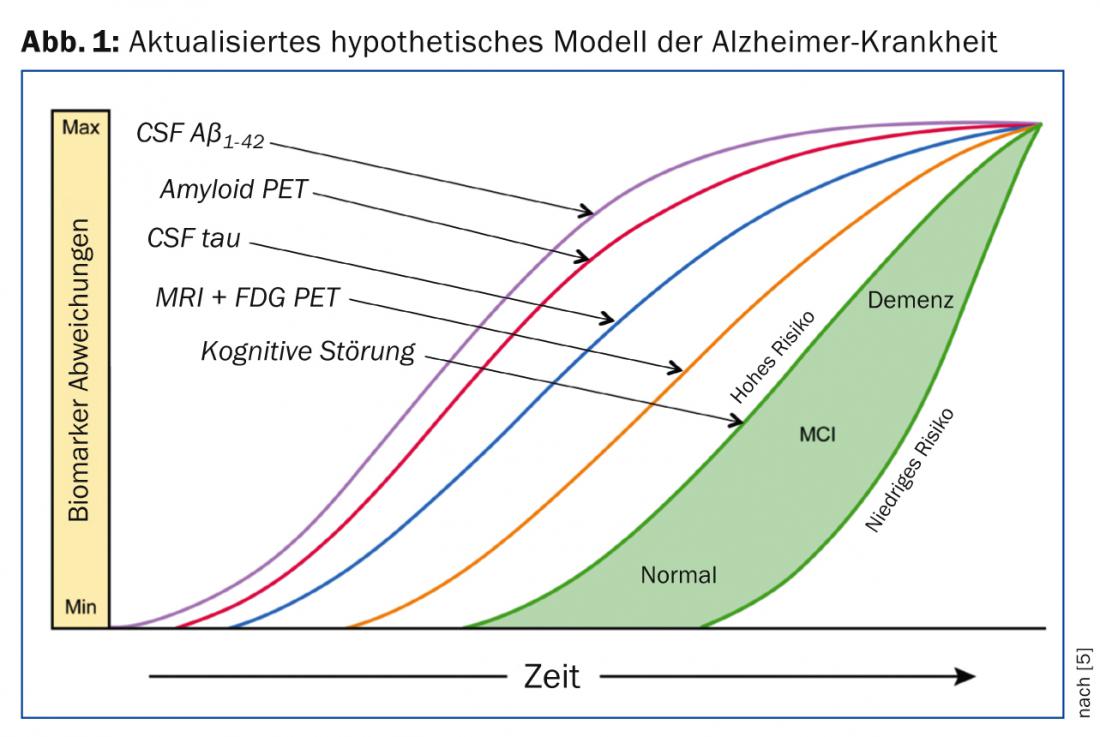

The lecture by Prof. Dr. med. Reto W. Kressig, Associate Professor of Geriatrics and Head Physician of the University Center for Geriatric Medicine at the Felix Platter Hospital in Basel, focused on innovations in dementia therapy. “The picture of the hypothetical development of Alzheimer’s disease is nice and clear (Fig. 1), but it is also just as hypothetical, since disease courses are very individual and difficult to predict,” is Prof. Kressig’s assessment.

Optimally, symptomatic treatment is adapted to the respective stage of the disease. Appropriate therapies are needed to achieve this, as several pivotal trials have been discontinued in recent years and substances such as tramiprosate, tarenflurbil, dimebon or IVIG have failed.

Prof. Kressig gave an overview of the state of the art in dementia therapy. From the vaccination studies, which initially seemed extremely hopeful, it has since been learned that while cognitive improvement has been achieved in animal studies, this effect has not yet been seen in humans with dementia. Another difficulty is that vaccination must occur before the onset of dementia symptoms. “However, vaccinating an entire population is definitely not recommended for reasons of side effects and cost,” Prof. Kressig assessed.

Substances specifically approved for the symptomatic treatment of dementia include cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) such as donepezil (Aricept® and Donezepil® in Switzerland), the rivastigmine Exelon® and the galantamine Reminyl® and galantamine Mepha®, as well as the NMDA antagonist memantine in the form of Axura® and Ebixa®. Two studies have demonstrated the clinical efficacy of both donepezil [6] and galantamine [7] in patients with very mild AD. For the higher dose of the Exelon® patch (15 vs. 10 cm2), additional improvement was also recently observed [8]. However, the possible gastrointestinal side effects must be kept in mind here.

Other therapeutic options, although not approved specifically for dementia, include antidepressants, antipsychotics, vitamins E and C, and gingko biloba, cerebrovascular agents, antioxidants, statins, and several more.

Optimal treatment – always together with relatives

When should treatment be started and when should it be stopped? These are issues that concern the practitioner in family practice. Prof. Kressig’s answer: Therapy should be started as early as possible. Analogous to the 2013 Boston AAIC recommendations, it is recommended to start with AChEIs and later add memantine. The corresponding contraindications, if any, must be observed: For AChEIs, these are severe, active gastrointestinal bleeding or peptic ulceration, arrhythmias or cardiac disease, seizure disorders, or syncope; for memantine, poor renal function: if the glomerular filtration rate is lower than 30, the dose should be halved. Further, a multimodal approach with pharmacologic treatment should occur as one of several parallel therapeutic approaches. “Treatment should only be stopped again when the patient is in the final stages of dementia or there is no indication for medication,” is Prof. Kressig’s response to treating physicians.

Regarding combination therapy of ChEI and memantine, although there are studies showing that patients on combination therapy were 3-7 times less likely to be admitted to a nursing home than patients treated with ChEI alone. No association was found between medication and time to death [9]. In 2012, the FOPH decided against recommending combination therapy because the evidence was insufficient. “The reason was the negative DOMINO study [10]. However, I suspect that the positive effects of combination therapy did not hold up statistically because of the high drop-out rate of 72%. This is because among the patients remaining in the study, combination therapy was still the best option,” was Prof. Kressig’s interpretation of the results. Furthermore, nutrition can also play a role. Here, Souvenaid showed improvements in memory performance in mild dementia, for example [11, 12].

Prof. Kressig concluded his lecture with the following assessment: “In the therapy and support of dementia patients, one must above all not underestimate the importance of the so-called “care-givers” such as family, patients and caregivers, since they have a large share in the well-being of the patient.” This was to be confirmed in the workshops that followed: The “brain theater” under the direction of Franziska von Arb performed various scenes from life with or as a dementia patient. The audience was able to witness the different perceptions and opinions of the protagonists. How is the worried, yet stressed daughter? Where do generous promises in the wills of ill persons to recently found life partners come from and how should they be dealt with? How can the physician’s proper approach and communication skills in various situations be improved to achieve the desired goal? All these questions were discussed in the interactive and lively interaction of the actors of the Brain Theater, the experts and the audience.

Source: 3rd Basel Dementia Forum, November 21, 2013, Basel.

Literature:

- American Psychiatric Association. SDM-5 2013.

- Stähelin HB, Monsch AU, Spiegel R: Int Psychogeriatr 1997; 9 Suppl. 1: 123-130.

- Ehrensperger MM, et al: Forthcoming.

- Ehrensperger MM, et al: Int Psychogeriatr 2010; 22(1): 91-100.

- Clifford R J, et al: Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 207-216.

- Seltzer B, et al: Arch Neurol. 2004 Dec; 61(12): 1852-1856.

- Orgogozo JM, et al: Curr Med Res Opin. 2004; 20: 1815-1820.

- Cummings J, et al: Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2012; 33: 341-353.

- Lopez OL, et al: J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009; 80(6): 600-607.

- Howard R, et al: N Engl J Med 2012; 366(10): 893-903.

- Scheltens P, et al: Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2010; 6: 1-10.

- Scheltens P, et al: J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2012; 31: 225-236.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(1): 48-50

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2014; 12(2): 36-39.