Talking about the behavior of the heart under the effect of physical performance is tantamount to a (pleasant) return to the history of sports medicine, because the study of the “vital organ” was one of the first tasks of the then still young subject. The term “sports heart” was defined primarily by means of percussion, auscultation, and x-ray and is still used today, but with somewhat greater accuracy thanks to the use of new technologies. How does the heart react to sporting activities and which changes are training-related, which are pathological? This is what the following will be about.

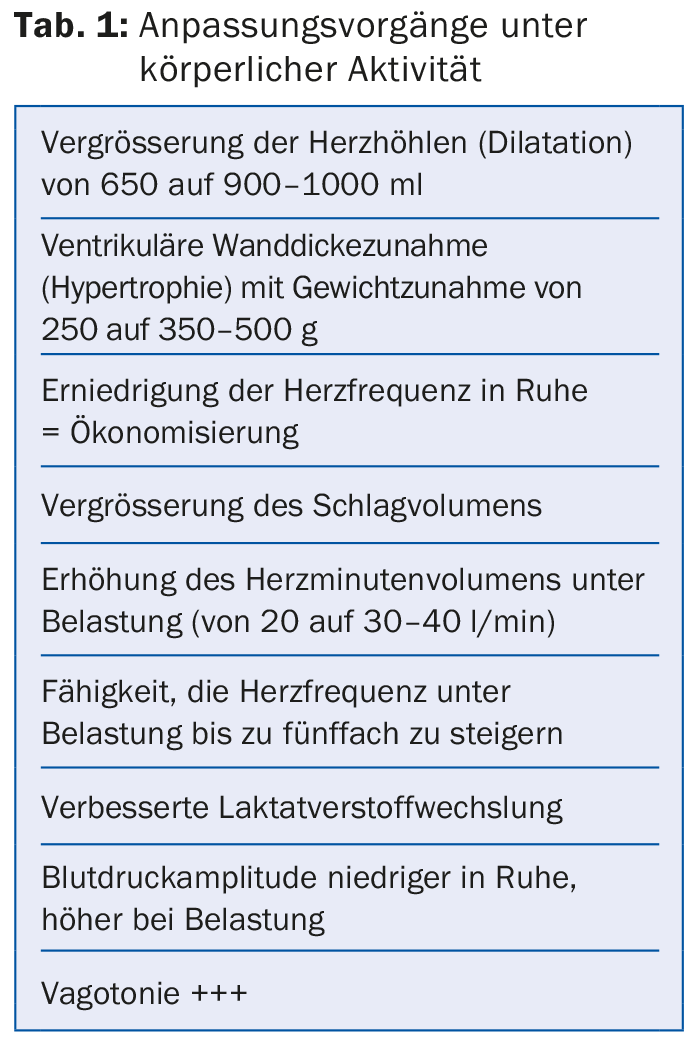

Basically, like most organic structures, the special striated muscle tissue myocardium responds to measured and repetitive stimuli. Table 1 shows the most important adaptation processes under physical activity at the level of the heart.

It goes without saying that the effects of training do not stop at the heart, but also cause, among other things, adaptations in the circulatory and neuro-vegetative systems, which in turn affect the heart. These structural and functional adaptations lead to exercise-induced physiological changes in the athlete’s resting ECG in up to 80% of recordings, which understandably can present some problems. This is because it is not easy, even for the trained, to distinguish these physiological from pathological ECG changes.

One could retort that the young and basically healthy athlete rather rarely needs an ECG workup – this is quite possible. But with the (sensible) advocacy of sports physicals worldwide, almost all SPU models recommend the resting ECG, which then brings to light just these frequent changes. Clean interpretation is essential at this stage to maintain the value of the examination, but more importantly, to prevent troubling and costly additional examinations wherever possible.

The pitfalls of modern technology

This problem of interpreting an apparently “non-normal” athlete’s ECG is compounded by the fact that in most cases the examined athlete is completely asymptomatic, which can create uncertainty for the physician. Last but not least, modern technology does not help much: on certain ECG recorders, an integrated computer program interprets the curves, which can lead to the most absurd findings with highly pathological descriptions (infarction, etc.). In this context, it goes without saying that in the presence of symptoms (syncope, dizziness, shortness of breath, chest tightness during exercise, palpitations or stuttering, performance kink, Marfan’s morphology, etc.) and/or with a positive personal and family history (sudden cardiac death in the family), suspicious ECG changes must be further clarified.

What do the guidelines say?

The scientific cardiology societies of Europe and America (or their sports medicine working groups) have seriously addressed this specifically sports medicine problem and issued clear guidelines in recent years. The publication of the Seattle Criteria in 2013 further clarified the question.

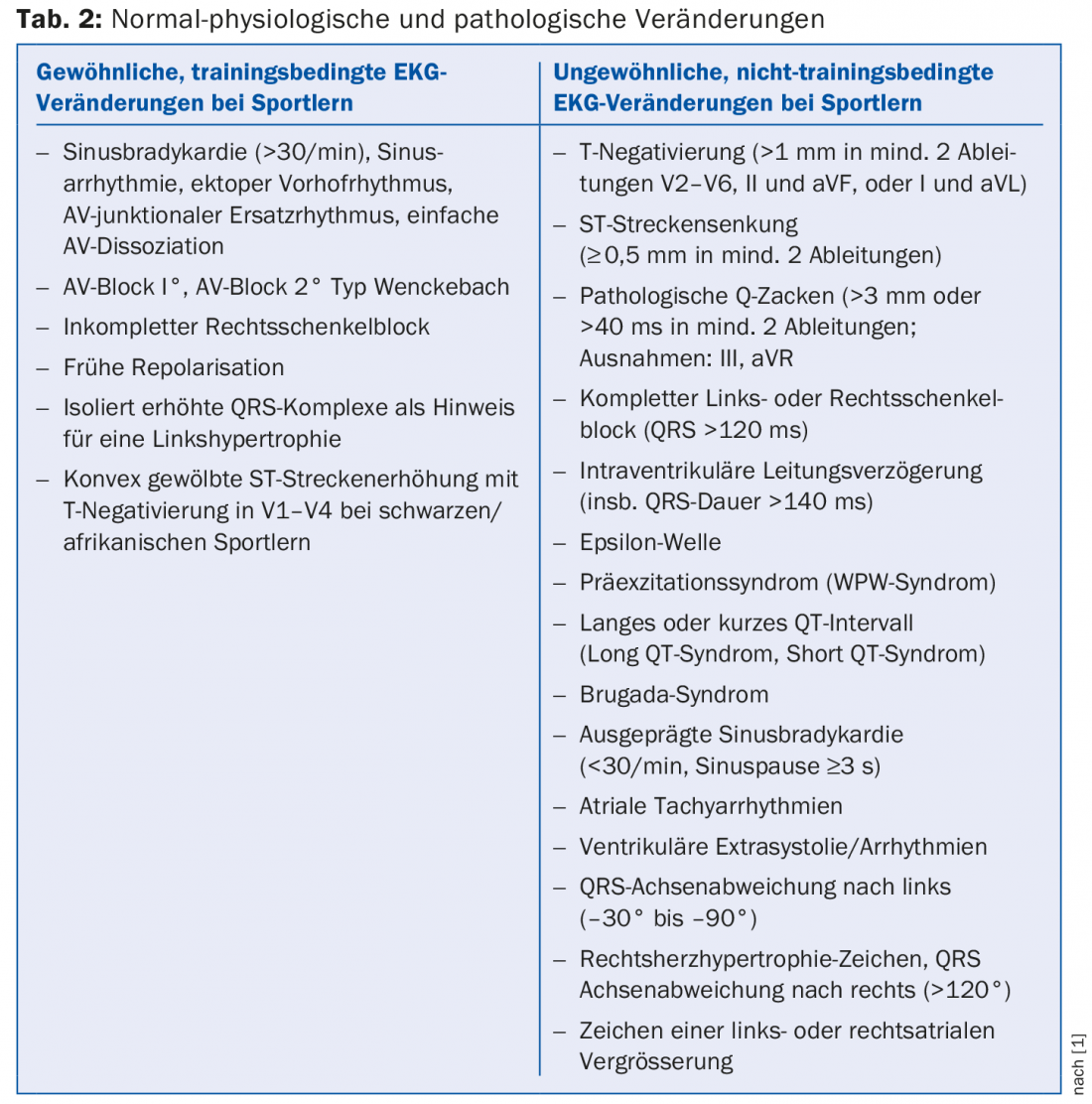

Today, according to professional society recommendations, athlete ECG changes are divided into “common, exercise-related” and “uncommon, non-exercise-related” changes and into cardiomyopathies and primary electrical heart disease according to the Seattle criteria, which entails higher specificity with preserved sensitivity compared with previous classifications. Table 2 shows this subdivision [1].

Reading this table, especially regarding the column on the right, will be rather scary for the non-specialist, and it is gratifying that, thanks to the research of a Swiss scientist, a major manufacturer of ECG equipment has now developed reading software that is also very suitable for sports ECGs. There are also online training opportunities for physicians to interpret the athlete ECG (see [2]).

The 12-lead ECG, as an adjunct to history and clinical examination, has clearly demonstrated its value in evaluating athletes in search of potentially lethal cardiac abnormalities that could lead to sudden death: ECG can diagnose up to 90% of cases in one of the major causes, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, up to 80% in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, and a high number in electrical disorders as well. Thus, the importance of a correct interpretation does not need to be underlined.

Literature:

- Drezner JA, et al: Electrocardiographic interpretation in athletes: the “Seattle Criteria”. Br J Sports Med 2013; 47: 122-124.

- http://learning.bmj.com/ECGathlete. Last accessed 7.5.2015

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(5): 6-7