Headaches in children are often underestimated, but occur frequently with a prevalence of 79%. Due to genetic predisposition and functional impairment already from (pre-)school age, migraine is the most important. Therefore, it should be diagnosed early and treated individually.

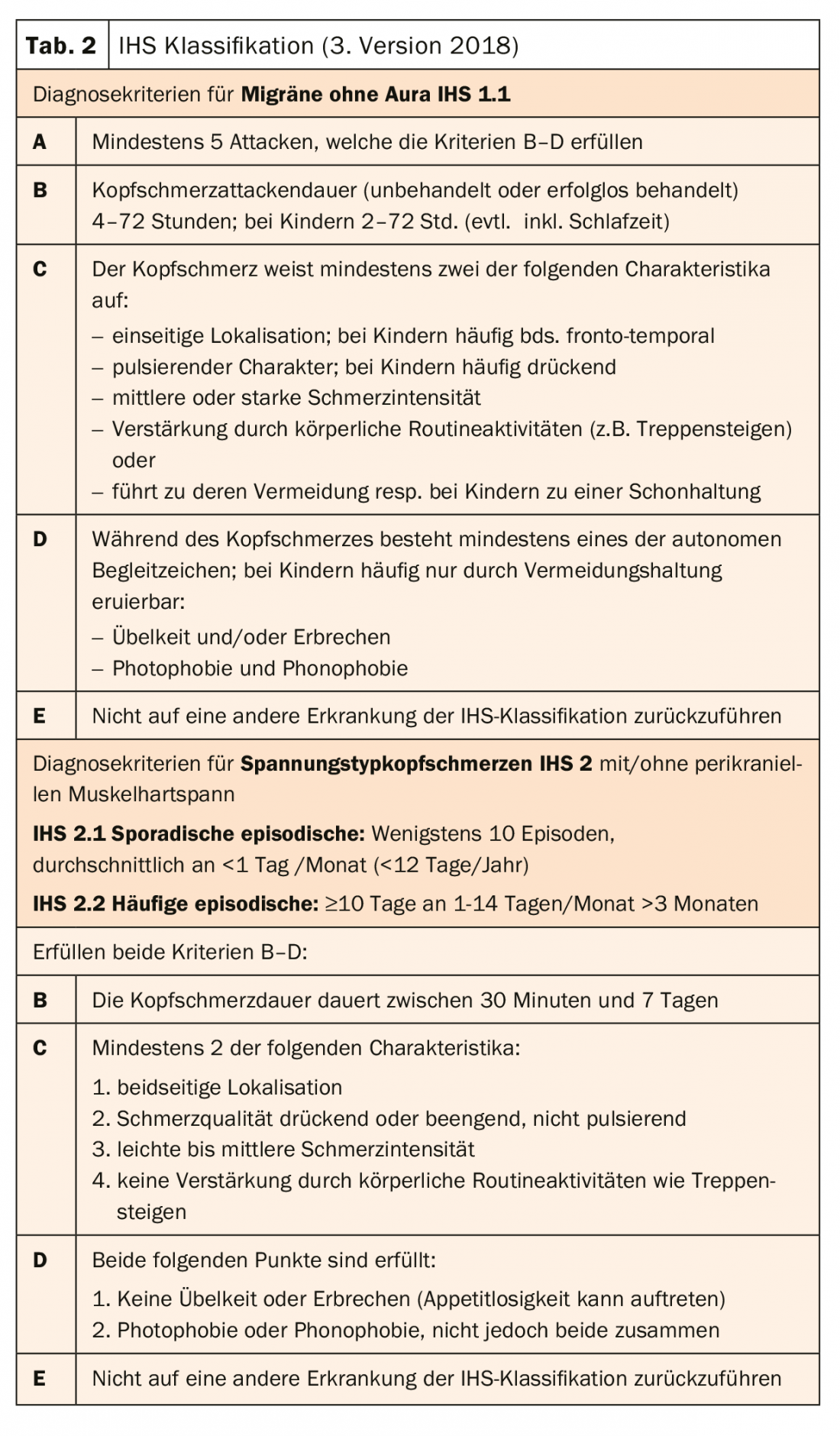

For parents, the primary concern is to delineate “secondary,” and thus potentially threatening, KS as a result of an underlying condition. However, these are much rarer compared to the primary ones. Alarm signs in the history and/or neurological examination such as the most common pathological findings congestive papillae, ocular motility disorders, focal signs, ataxia or meningeal signs increase the sensitivity of secondary KS, and must be actively explored and further clarified individually with imaging, lumbar puncture, etc. [4] (further “red flags” Tab. 1). Conversely, a normal neurologic examination excludes secondary KS with a high probability. Particular attention must be paid to per/acute severe, chronic progressive and KS in children <5 years [5].

In the absence of a sensitive biomarker, primary, “brain-intrinsic” headaches such as migraine and tension-type headache cannot yet be reliably proven, which in principle implies a diagnosis of exclusion. However, many studies show with good evidence that recurrent headache can be reliably diagnosed clinically using the International Headache Society (IHS) criteria, and a detailed neurological examination taking into account the dynamics from school age [4,6,7].

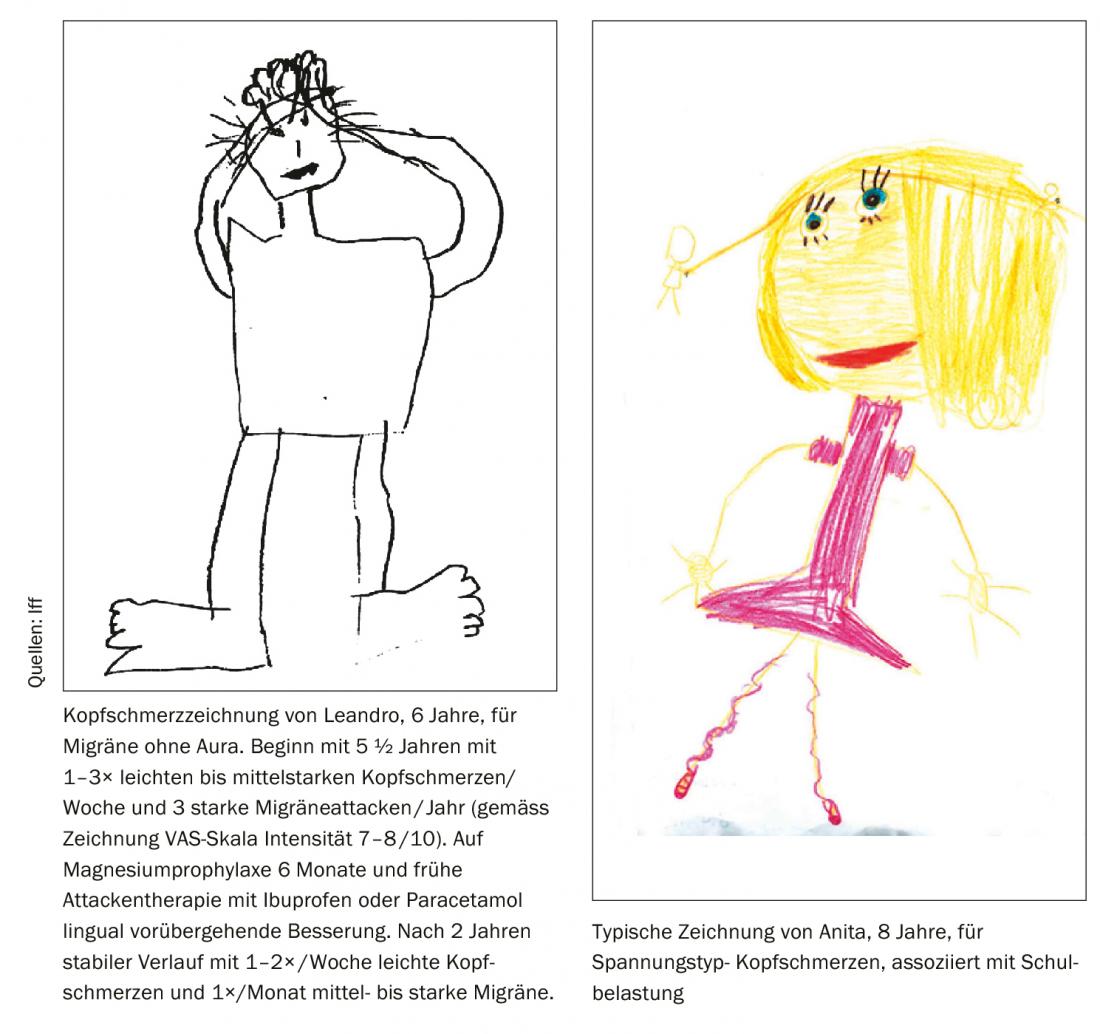

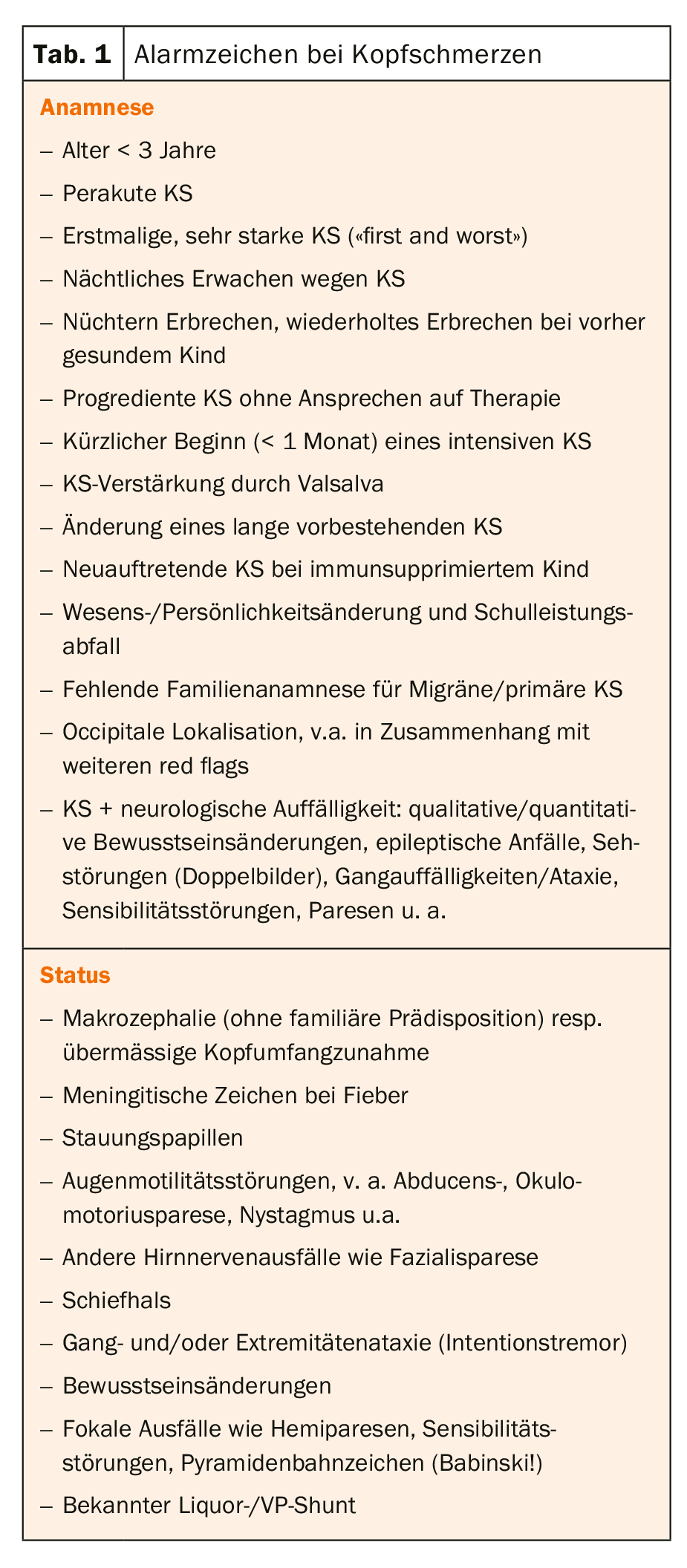

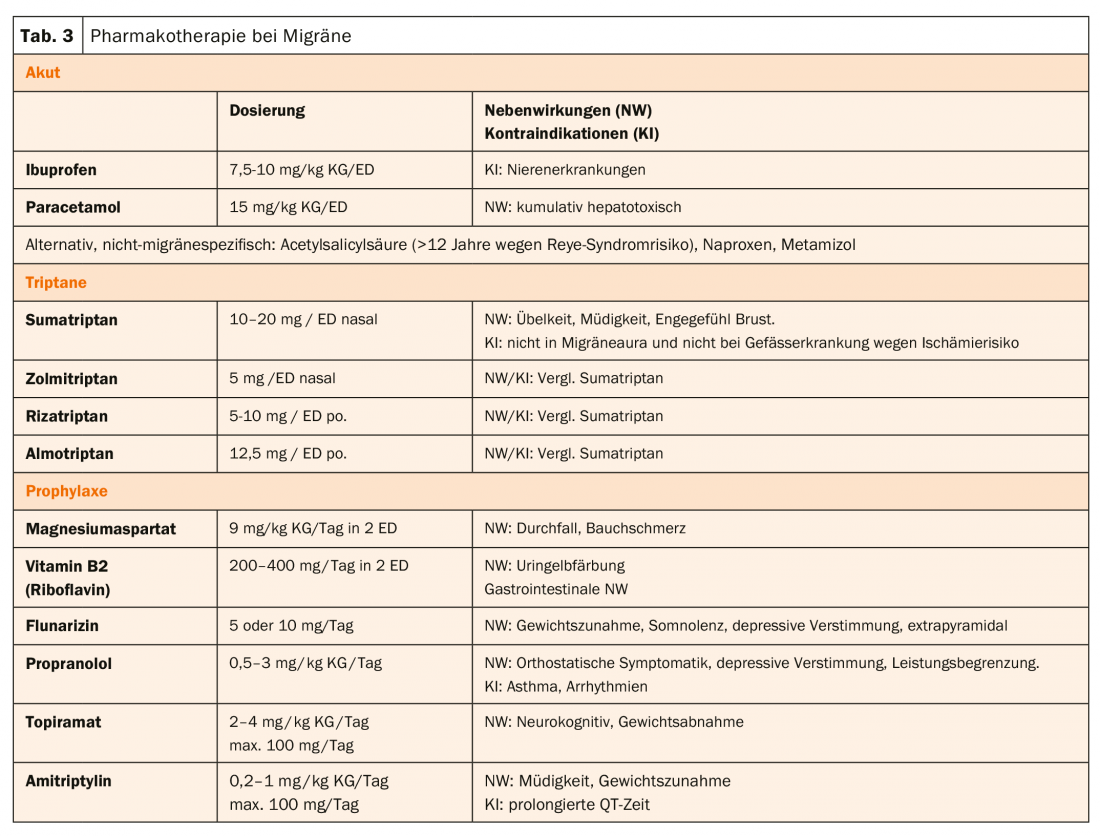

A migraine usually manifests itself less severely and for less time in childhood than in adults. Typically, children also perceive these more frontally than unilaterally, and not as pulsating but pressing pain. Characteristic migraine symptoms such as headache aggravation due to routine activity/shaking or photo-phonophobia/phonophobia are usually indirectly induced in childhood by shaving or other forms of headache. avoidance attitude was observed, which is why the IHS criteria were specifically adapted for childhood migraine [6] (Table 2).

Vertigo is not listed in it, although it is frequently perceived and underlying (vestibular) migraine is the most common cause [8]. Also, the important genetic predisposition with positive family history in 80-90% of first-degree relatives (N.B: most parents refer to their migraine as “normal headache”!) and the 4-fold increased relative risk for migraine with aura are not included in the IHS criteria. Hormonal changes additionally play a significant role in the female sex, in that migraine in girls begins on average at 10.6 years of age at the onset of pubertal development and/or develops with hormonal treatment and anticonception or pregnancies resp. menopause can change significantly. IHS criteria for tension-type headache are the same in children as in adults [6].

Treatment

General: Headache treatment in children/adolescents is oriented towards a reduction in quality of life and aims at a rapid return to normal daily function as well as frequency reduction of frequent migraine. It consists of acute and preventive pharmacological and non-pharmacological measures. Although “psychoeducation” of lifestyle measures (sufficient, individually determined amount of sleep regular drinking and meal rhythm as well as weekly, athletic endurance activity, avoidance of trigger factors) is at least as important as pharmacotherapy and already frequently results in a significant improvement of the headache situation, in the case of prolonged and more severe migraine attacks, it should be >½-¾ hrs of impossible sleep or insufficient improvement due to this, pharmacotherapy should not be dispensed with even from infancy. Efficacy must be greater than with placebo, which in children means greater than 50% improvement in pain within 1-1½ hr, evaluated with the VAS scale. Even if tension-type headache is less disabling than migraine, associated depressive or psychosomatic symptoms should be investigated and included in (causal!) treatment. Pharmacotherapeutic acute measures should also be used very cautiously in these, but in principle in the same dosage as in migraine [9]. Non-pharmacological measures such as cognitive behavioral therapy, biofeedback, relaxation exercises, and others should be included individually as part of a multimodal pain management for frequent headaches [3].

Pain medications generally should be used on no more than 10 to 15 days per month (NSAIDs 15 days, triptans 10 days) because of the risk of chronic medication overuse headache (MCS) with prolonged use [10], especially in adolescents. Therapy monitoring with a headache calendar is therefore essential (e.g., at www.headache.ch).

Acute pharmacotherapy is listed in Table 3: predominantly, the two general analgesics ibuprofen and acetaminophen are used in sufficiently high doses and early (even in school!) in the migraine attack course, although ibuprofen was more effective in individual studies, and is therefore therapy of first choice.

In case of non-significant effect by these analgesics, which is observed repeatedly in childhood migraine over the years usually from adolescence onwards, the migraine-specific triptans are used. In Switzerland, only sumatriptan 10 or 20 mg nasal is approved for use in patients 12 years of age and older. However, based on international studies, the three other triptans Riza-, Zolmi- and Almotriptan can be used from 12 years of age, and “off-label” in Switzerland, with evidence-based efficacy, including max. 2×/day. If a debilitating, prolonged migraine attack over 72 h (status migränosus) cannot be adequately treated with triptans on an outpatient basis, newer algorhythms exist with intensified pharmacotherapy with administration of sumatriptan s.c., i.v. metoclopramide (caveat: extrapyramidal NW) and magnesium sulfate, among others, on an emergency basis [10].

Preventive pharmacotherapy is indicated from a migraine frequency of 3-4×/month, when acute therapy is not effective, in cases of medication overuse headache, in cases of repeatedly prolonged attacks and risk of migraine progression (Tab. 3). The latest, American guidelines paraphrase this indication less precisely with “frequent headaches or/and migraine-related limitation” as well as MüKS [11].

Often, especially in children and adolescents, the dietary supplements magnesium or/and vitamin B2 help, but only from (1 to) 2-month use. Without significant improvement (≤50% attack frequency reduction) of frequent migraine, other medications such as flunarizine, beta blockers, amitryptiline, and topiramate should be considered if significant impairment is present. Just for the last two, the recent CHAMP (Childhood and Adolescence-Migraine Prevention) trial demonstrated evidence-based efficacy equal to placebo but with more drug-related side effects. Since this study did not involve severely affected patients (PedMIDAS score >50), amitryptiline and topiramate may still be used in individual cases [12].

In general, preventive pharmacotherapy should be discussed individually, taking into account the migraine-related limitation as well as the benefit/risk profile with information about the possible side effects.

If proven effective and tolerable, prophylaxis will be continued for a total of 6-12 months (or depending on individual limitation), as will continued adherence to the aforementioned lifestyle measures.

Migraine progression

Presumably, a large number of patients exist who control a rare migraine well with gentle posture and common pain medications and never consult their physician. However, as the frequency of migraine increases, the risk of chronic migraine increases in both adulthood (5-8%) and adolescence (1-2%). Therefore, even in childhood/adolescence, caution is advised at a frequency of ≥1×/week, and multimodal therapy should be considered, as this may lead to a significant reduction in the long term [3]. In addition to headache frequency, obesity, depression, and MüKS may also play a role as risk factors for migraine progression to chronic migraine (definition: >15 headache days with ≥8 migraine days/month) in adolescence. From my experience, this may also apply to inadequate attack therapy demonstrated in adulthood for children as well [13].

For adults with relevantly debilitating migraine without efficacy of usual preventive measures, migraine-specific prophylaxis with subcutaneously injected monoclonal CGRP (Calcitonin Gene Related Peptide) antibodies 1×/month has been available for three years. Currently, erenumab as a CGRP receptor antibody (Aimovig®) and galcanezumab as an antibody against the peptide itself (Emgality®) are approved in Switzerland under certain conditions, which were able to significantly reduce the migraine frequency of ≥8-9 migraine days/month by half in recent studies, with good tolerability. In childhood and especially adolescence, there are still no study data for this group of medications, and only recommendations from the American Headache Society for use in ≥8 migraine days/month with significant limitation (PedMIDAS score >30) and two so far unsuccessful pharmacological preventive measures in postpubescent and, in individual cases, prepubescent adolescents [14].

Literature:

- Ozge A, Sasmaz T, Cakmak SE, et al: Epidemiological-based childhood headache natural history study: After an interval of six years. Cephalalgia 30: 703-712; International Headache Society 2010.

- Dooley JM, Augustine HF, Brna PM, Digby AM: The prognosis of pediatric headaches–a 30-year follow-up study. Pediatr Neurol. 2014 Jul; 51(1): 85-87. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.02.022. Epub 2014 Mar 5.

- Charles JA, Peterlin BL, Rapoport AM, et al: Favorable outcome of early treatment of new onset child and adolescent migraine-implications for disease modification. J Headache Pain 2009; 10: 227-233.

- Lewis D, Ashwal S, Dahl G, et al: Practice Parameter: Evaluation of children and adolescents with recurrent headaches. Neurology 2002; 59: 490-498.

- Kelly M, Strelzik J, Langdon R, Di Sabella M: Pediatric headache: overview. Curr Opin Pediatr 2018, 30: 748-754

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018, 38(1): 1-211.

- Ebinger F: Headache. Pediatrics up2date 2011; 3: 271-289.

- Langhagen T, Landgraf MN, Huppert D, et al: Vestibular Migraine in Children and Adolescents. Curr Pain Headache Rep (2016) 20: 67.

- Anttila P: Tension-type headache in childhood and adolescence. Lancet Neurol 2006; 5: 268-274.

- Kacperski J, Kabbouche MA, O’Brien HL, Weberding JL: The optimal management of headaches in children and adolescents. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2016; 9: 53-68.

- Oskoui M, Pringsheim T, Billinghurst L, et al: Practice guideline update summary: Pharmacologic treatment for pediatric migraine prevention. Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology; 2019; 93: 1-10.

- Powers SW, et al: Trial of Amitriptyline, Topiramate, and Placebo for Pediatric Migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017 January 12; 376: 115-124.

- Buse DC, Greisman JD, Khosrow B, et al: Migraine Progression: A Systematic Review Headache 2018; 0: 2-33.

- Szperka CL, et al. Recommendations on the Use of Anti-CGRP Monoclonal Antibodies in Children and Adolescents. Headache 2018; 58:1658-1669.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(6): 24-27.