More than just a “gut feeling”: antibiotic reduces depression behavior via changes in the composition of the intestinal flora and thereby inhibits an “inflammatory process” in the brain.

Depression is one of the most common mental illnesses. Nearly one in five will be affected at some point in their lives. At least 350 million people worldwide suffer from depression.

Our psyche is regulated by various influences: the immune system, the interaction of our hormones, but also the intestinal flora, the microbiome. The bacteria of the intestinal flora are not only important for digestion, but the composition of the microbiome even significantly determines our emotional well-being and seems to be altered in depressed patients. In a study published in the online journal Translational Psychiatry, neurobiologists led by Prof. Dr. Inga Neumann, Chair of Animal Physiology and Neurobiology at the University of Regensburg, in cooperation with the teams of Prof. Dr. Rainer Rupprecht, Chair of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy at the Regensburg District Hospital, Prof. Dr. Andre Gessner from the Institute of Clinical Microbiology and Hygiene at the University Hospital Regensburg, and Prof. Dr. Isabella Heuser, Charite Berlin, investigated the exact relationship between emotionality, depression and microbiome in laboratory rats. This demonstrated that in rats that are particularly anxious and also exhibit treatment-resistant depression behavior, the composition of the gut microbiome differs greatly from normal, non-anxious animals. If the anxious animals are treated with the antibiotic minocycline, not only the intestinal flora is strongly changed as expected. The animals also behave more actively and show less depression-like behavior.

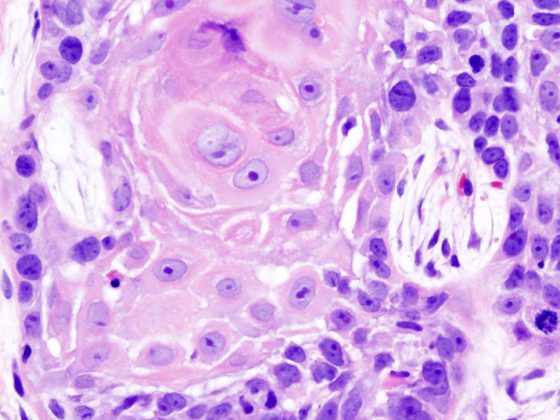

How can it be that an antibiotic affects animal behavior? In addition to its effect on gut bacteria, minocycline altered so-called glial cells in the brain, formerly known as the “glue” of the brain, which regulate numerous brain functions. Depression is associated with activation of microglia, which is also interpreted as an inflammatory process of the brain.

Prof. Neumann’s team has now succeeded in demonstrating that the composition of the microbiome changes after minocycline treatment: Some bacterial families become rarer, others become more frequent, especially those bacterial families that produce short-chain fatty acids These enter the bloodstream and can also influence the brain in this way. One of these substances – butyrate – can even prevent the activation of microglia in the brain, thus having an anti-inflammatory effect. Therefore, the antidepressant effect of minocycline is most likely due to this effect.

Source: DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-019-0556-9

GP PRACTICE 2019; 14(9): 44