Accurate diagnosis lays the foundation in the presence of double valve pathology aortic valve stenosis / mitral valve stenosis. Since the two pathologies influence each other, a multimodality approach including invasive, imaging, and functional assessment is a prerequisite but remains a challenge even in experienced hands. An individual therapy strategy is formulated based on anatomical conditions, age and comorbidities, as well as the desired therapeutic goal. The full range of surgical, percutaneous, and combined interventions should be considered. The complex diagnostic investigations and the performance of various operations and percutaneous interventions suggest the involvement of a broad-based heart team.

Symptomatic aortic valve stenosis is the most common representative of degenerative valvular heart disease. Accordingly, the treatment options are innovative and diverse, encompassing a wide range of curative therapies from surgical aortic valve replacement to catheter-based valve replacement (TAVI). Today, the perioperative lethality risk for isolated surgical aortic valve replacement is reported to be less than 3.5% and the 30-day mortality risk for high-risk patients treated with TAVI valve is reported to be less than 15% [1,2]. In a surgical double valve procedure, the perioperative risk increases to %–13% [3,4]. If aortic valve stenosis is accompanied by mitral valve regurgitation (MI), this may significantly influence the strategic approach to therapy of aortic valve stenosis. The prevalence of aortic valve stenosis accompanied by at least moderate MI has been reported to be as high as 33% [2]. The wide variation in prevalence can be explained by the partly different definition of a relevant MI in the literature. The fact remains, however, that in a relevant proportion of patients with aortic valve stenosis, the question of a concomitant MI requiring treatment arises. The numerous surgical and interventional therapeutic procedures now available allow therapy to be tailored to the individual risk and anatomic characteristics of the patient, thus helping to minimize peri-interventional risk.

Treatment strategy for severe AS and concomitant MI.

The key points defining therapy in complex combined aortic and mitral valve vitiation are thorough diagnosis of the mechanisms and assessment of the spontaneous course of MI after correction of aortic valve stenosis. Thus, when determining the optimal treatment strategy, it is worthwhile to conduct a precise investigation of the MI that identifies the underlying causes and places them in the context of the resulting pathophysiology. Based on the knowledge gained, the most appropriate therapy for the patient can be selected from the various therapeutic options.

Cause of mitral valve regurgitation

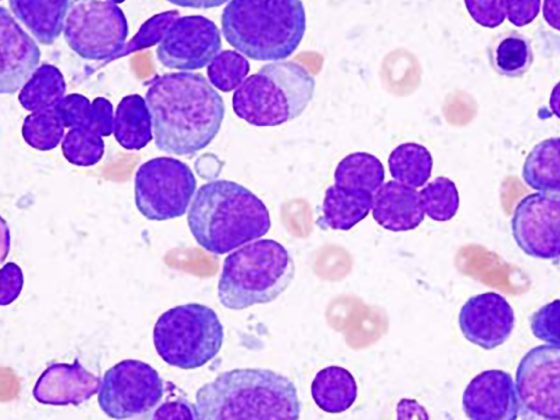

Generally, a distinction is made between an organic MI and a functional MI. Whereas in organic MI the structural valve apparatus (leaflet valves, chordae, papillary muscles, annulus) generates the leak, in functional MI the valve apparatus as such is intact and the mitral valve leaks as a result of a structural geometry change of the left ventricle. Typical representatives of organic MI are tendon filament ruptures or elongations and myxomatous or atherosclerotic changes, with myxomatous changes being the most common. Functional mitral valve insufficiencies have in common that due to the altered ventricular geometry the actually intact valve apparatus no longer ensures a clean coaptation of the leaflets. MI does not necessarily have to be based on a global disturbance of ventricular geometry, as regional disturbances can already lead to a relevant MI. It is not uncommon for this to be due to an ischemic cause. Often, MI also results from a combination of different functional and organic causes, which ultimately adversely affect ventricular geometry and coaptation area, leading to leakage.

Diagnostics

The workup for bivalvular disease involves multiple diagnostic modalities. These include right-to-left cardiac catheterization, transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography, and, in individual cases, stress echocardiography to evaluate MI under stress. Measurements of exercise capacity, such as ergometry or a 6-minute walk test, can also be used to unmask symptoms, concomitant ischemia, or indirectly measure deep stroke volume. The difficulty in the analysis of valvular pathology is that both pathologies influence each other. Severe aortic valve stenosis can lead to relevant MI simply because of the high afterload and resulting pressure overload in the left ventricle. However, severe MI may also result in markedly reduced forward stroke volume, and thus reduce the transvalvular gradient across the aortic valve, which may lead to misclassification of the severity of aortic valve stenosis. In such a case, to better assess the true severity of aortic valve stenosis, dobutrex stress echocardiography may be helpful. Complicating this is not infrequently reduced left ventricular function, which may further confound the degree of valve pathology. Thus, the correct assessment of the cause and severity of the valve pathology is often not based on a single measurement, but is often the result of a multitude of complementary examinations, which ultimately lead to a physiologically comprehensible logical interpretation of the results.

Therapy options

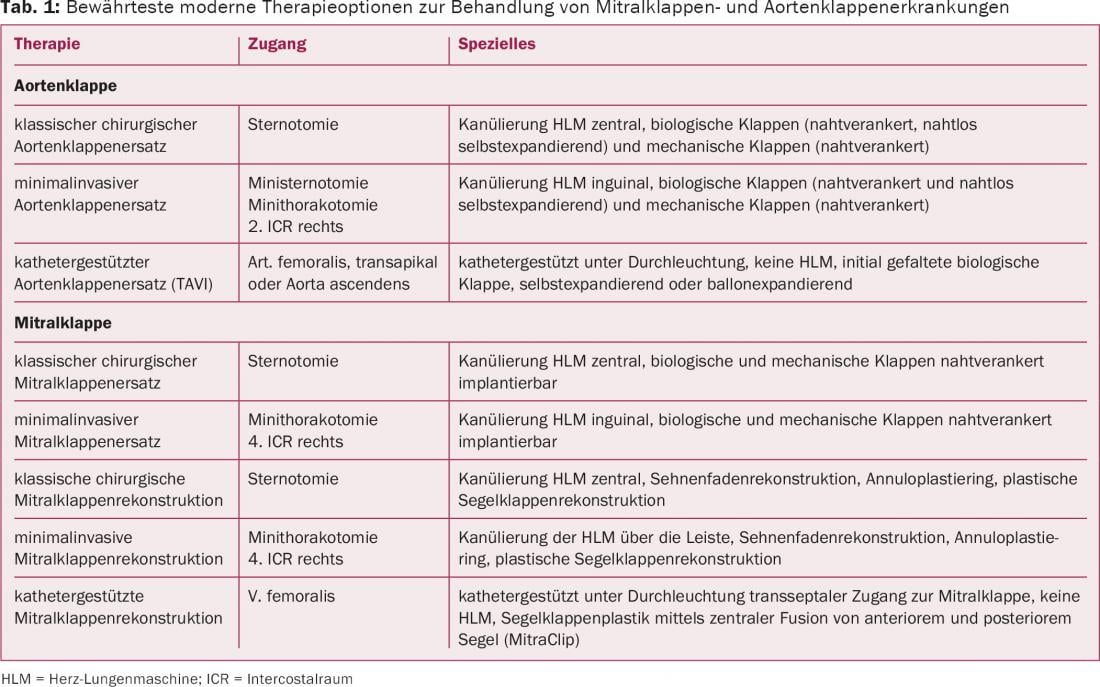

In recent years, the therapeutic options for the treatment of valvular pathology have undergone a strong development in both the surgical and interventional sectors. Table 1 provides an overview of the treatment options commonly used today.

Discussion

Regarding the treatment of concomitant mitral regurgitation in severe aortic valve stenosis, the following findings are valid: With regard to mortality and long-term survival, only cautious statements seem possible at present. What is clear, however, is that persistent moderate-grade MI promotes the development of relevant heart failure in the medium to long term [5–8]. Data are accumulating that functional mitral regurgitation in particular benefits from isolated aortic valve intervention [2,5,6,9–11]. To better assess the postoperative course of functional MI, concomitant unfavorable predictive clinical parameters such as impaired left ventricular pump function, pulmonary hypertension, concomitant atrial fibrillation, left atrial dilatation >5 cm, a preoperative transaortic peak gradient <60 mmHg, and concomitant aortic valve regurgitation with an end-systolic diameter <45 mm can be added [8,9].

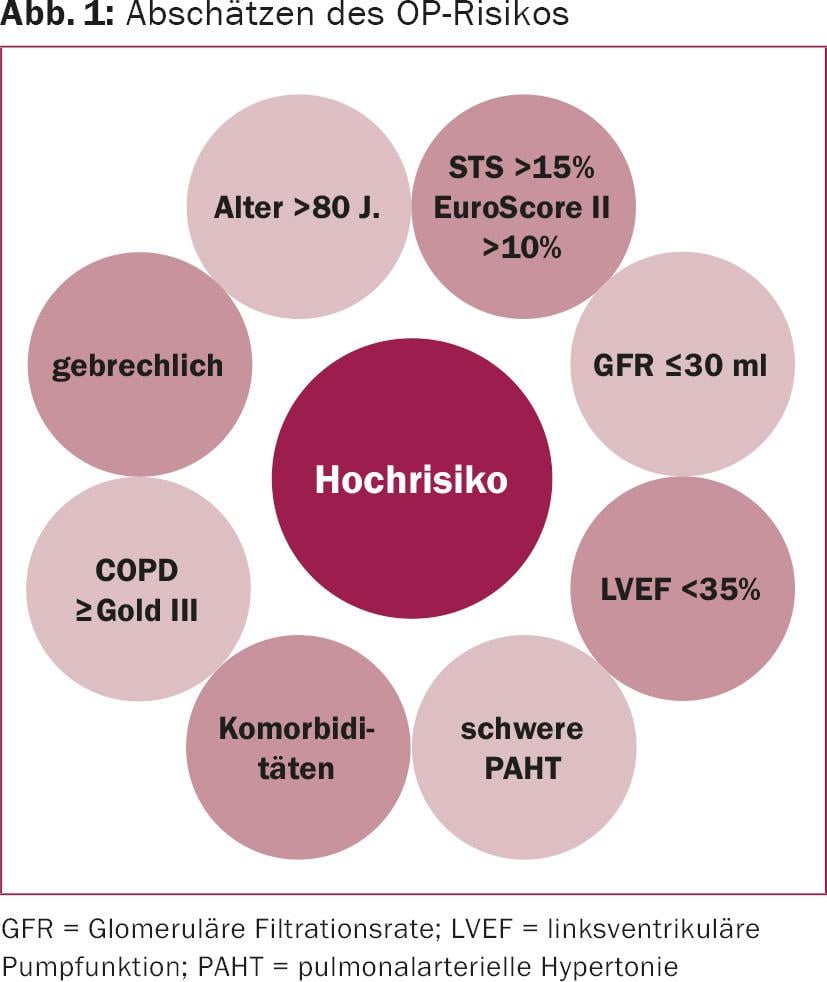

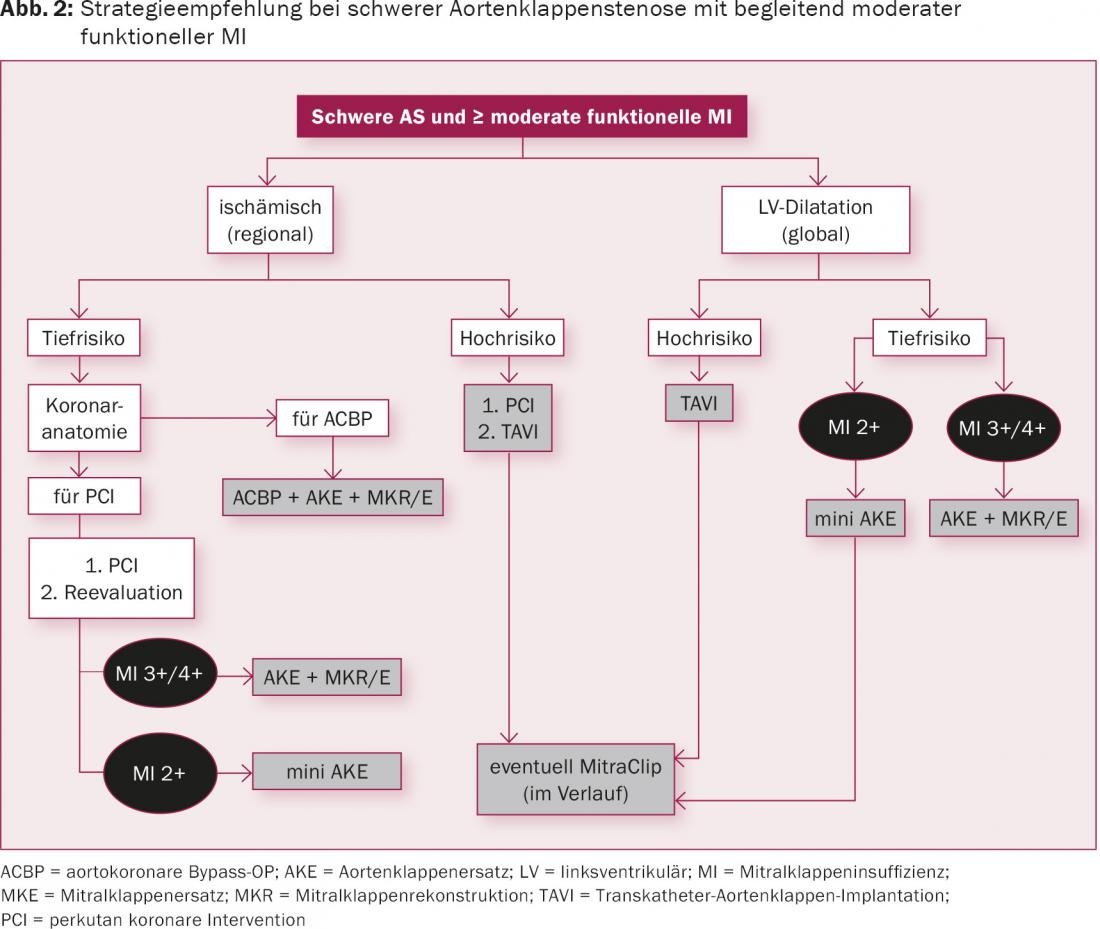

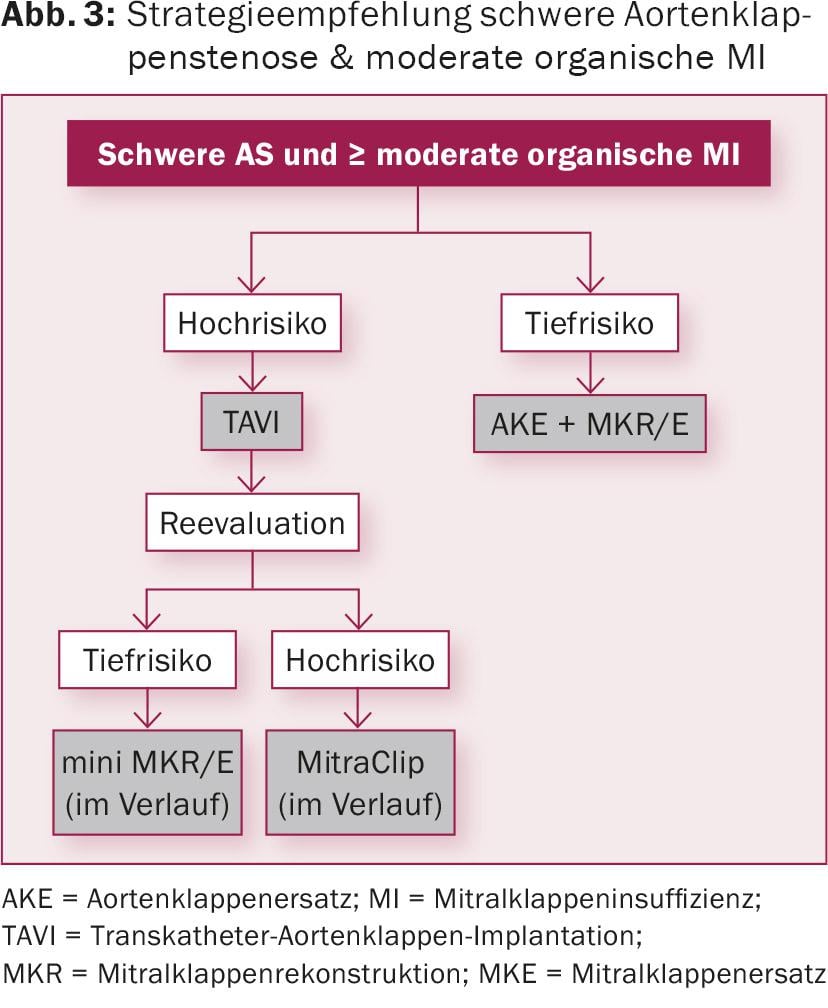

However, because of the complexity that may underlie MI, as well as the individual periinterventional concomitant risks, a blanket therapeutic proposal for severe aortic valve stenosis with concomitant moderate-grade MI falls short. This is reflected in both the ECS/EACTS and ACC/AHA guidelines, which essentially recommend treatment according to valvular disease and ventricular function [1,12].The studies suggest that functional MI in particular benefits from isolated aortic valve intervention. Here, left ventricular pressure drop and associated remodeling of ventricular geometry appear to favor MI most strongly. However, it should be kept in mind that posttherapeutic improvement of MI can be expected only in those patients in whom functional MI is a direct consequence of aortic valve stenosis and remodeling is still possible. A circumstance that is no longer necessarily present in patients in whom chronic afterload increase has already led to severe weakening of the left ventricle. In organically caused mitral regurgitation, remodeling after isolated aortic valve replacement also seems to have a beneficial effect. However, due to the valve structural defects, this effect is not equally pronounced. In our view, a systematic and interdisciplinary approach that takes into account the individual risks as well as the specific anatomical characteristics of MI is crucial for the successful treatment of concomitant MI (Fig. 1-3) .

Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate the strategy concept for organic and functional mitral regurgitation, respectively. It is obvious that accurate diagnosis lays the foundation for successful treatment. Since the two pathologies influence each other, a multimodality approach including invasive, imaging, and functional assessment is a prerequisite. Right-to-left cardiac catheterization, transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography, and, if necessary, stress echocardiography are helpful in this regard. The latter may be particularly helpful in isolated stress-induced MI. In addition, CT angiography of the aortic root and peripheral arteries can be performed in preparation for interventional therapy. Diagnostic analysis and resulting therapy should be performed by an interdisciplinary heart team (consisting of interventional and noninterventional cardiologists, cardioanesthesiologists, and cardiac surgeons). The interdisciplinary nature of the therapy proposal not only opens up a broad spectrum of treatment options, but also allows an approach tailored to individual needs and risks. From the various treatment options listed in table 1, the therapeutic concept that makes the most sense for the patient can finally be determined. For example, surgical management of a treatment-emergent MI in the setting of an initially weakened left ventricle may only become possible after recovery through afterload reduction using a gentler TAVI procedure.

In conclusion, concomitant functional mitral valve regurgitation in particular may improve after isolated aortic valve replacement. Concomitantly organic mitral valve regurgitation benefits from a double valve strategy in the long term. Concomitant severe mitral regurgitation, whether organic or functional, should be referred for double valve therapy. If the periinterventional risk is correspondingly high, a delayed hybrid procedure (first first valve interventional, then second valve surgical minimally invasive) may be helpful. The interdisciplinary nature of a Heart Team not only opens up a broad spectrum of different treatment options, but also allows therapy to be tailored to individual needs and risks.

Literature:

- Vahanian A, et al: Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease: The Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2007; 28: 230-268.

- Nombela-Franco L, et al: Significant mitral regurgitation left untreated at the time of aortic valve replacement: a comprehensive review of a frequent entity in the transcatheter aortic valve replacement era. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63: 2643-2658.

- Litmathe J, et al: Predictive risk factors in double-valve replacement (AVR and MVR) compared to isolated aortic valve replacement. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006; 54: 459-463.

- Harling L, et al: Aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis in patients with concomitant mitral regurgitation: should the mitral valve be dealt with? Eur Cardiothorac Surg 2011; 40: 1087-1096.

- Barreiro CJ, et al: Aortic valve replacement and concomitant mitral valve regurgitation in the elderly: impact on survival and functional outcome. Circulation 2005; 112: 1443-1447.

- Takeda K, et al: Impact of untreated mild-to-moderate mitral regurgitation at the time of isolated aortic valve replacement on late adverse outcomes. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2010; 37: 1033-1038.

- Coutinho GF, et al: Management of moderate secondary mitral regurgitation at the time of aortic valve surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2013; 44: 32-40.

- Ruel M, et al: Natural history and predictors of outcome in patients with concomitant functional mitral regurgitation at the time of aortic valve replacement. Circulation 2006; 114: 1541-1546.

- Toggweiler S, et al: Transcatheter aortic valve replacement: outcomes of patients with moderate or severe mitral regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 59: 2068-2074.

- Wyler S, et al: What happens to functional mitral regurgitation after aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis? Heart Surg Forum 2013; 16: E238-E242.

- Nombela-Franco L, et al: Clinical impact and evolution of mitral regurgitation following transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a meta-analysis. Heart 2015; 101: 1395-1405.

- Nishimura RA, et al: 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014; 148: e1-e132.

CARDIOVASC 2016; 15(1): 22-27