Swallowing is a sensorimotor process with voluntary and reflexive components. In addition to neurological and muscular diseases, swallowing disorders can be caused by tumor or surgery-related changes in the head and neck area, esophagus or stomach. Imaging examinations make the structures and processes involved visible. Therapeutic steps can be derived from the results of the dysphagia diagnosis.

In the articles on dysphagia, numerous local changes in the upper digestive tract were described. A rather rare cause of the functional disorder is an alteration of the brain stem with possible affection of the cranial nerves responsible for the act of swallowing. Lesions of the descending corticobulbar pathways to the brain stem, for example a mass or inflammatory changes following a heart attack, can cause acute swallowing problems.

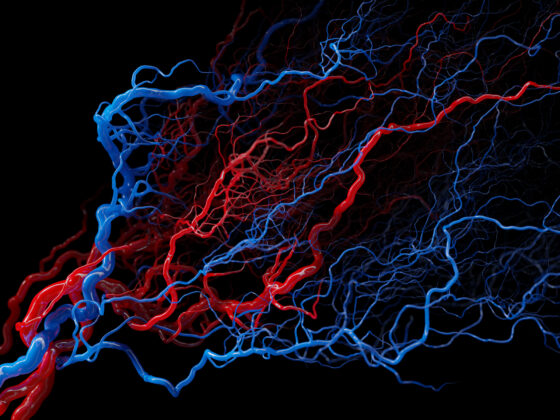

The act of swallowing is a complex process that requires the precise interaction of numerous muscles, controlled by various nerve centers and pathways. Successful swallowing requires closure of the nasopharynx and closure of the larynx by the epiglottis [1]. Normally we swallow between 600-2000 times a day. Outside of mealtimes, you swallow approx. 0.5-1.5 ml of saliva per swallow about once a minute when you are awake. For a small meal of 6 minutes we need approx. 32 sips. Hardly any saliva is produced and swallowed during deep sleep [2]. The nuclei of the five cranial nerves (trigeminal nerve, facial nerve, hypoglossal nerve, vagus nerve, glossopharyngeal nerve), which supply the 100 muscles of the organs involved in swallowing (cheeks, lips, jaw, tongue, soft palate, pharynx, larynx, hyoid bone, esophagus), are located in the area of the brain stem.

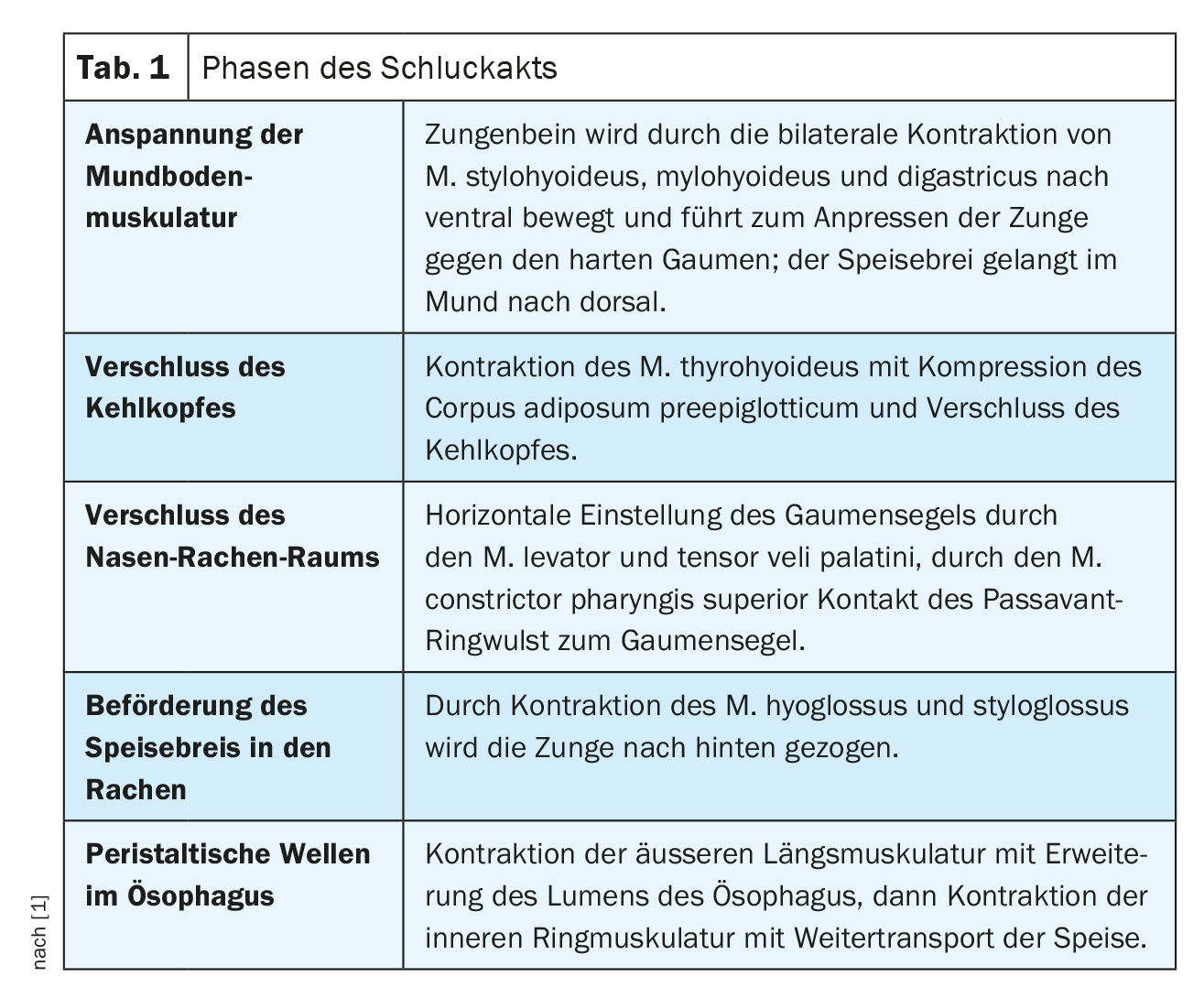

The swallowing process is shown in Table 1.

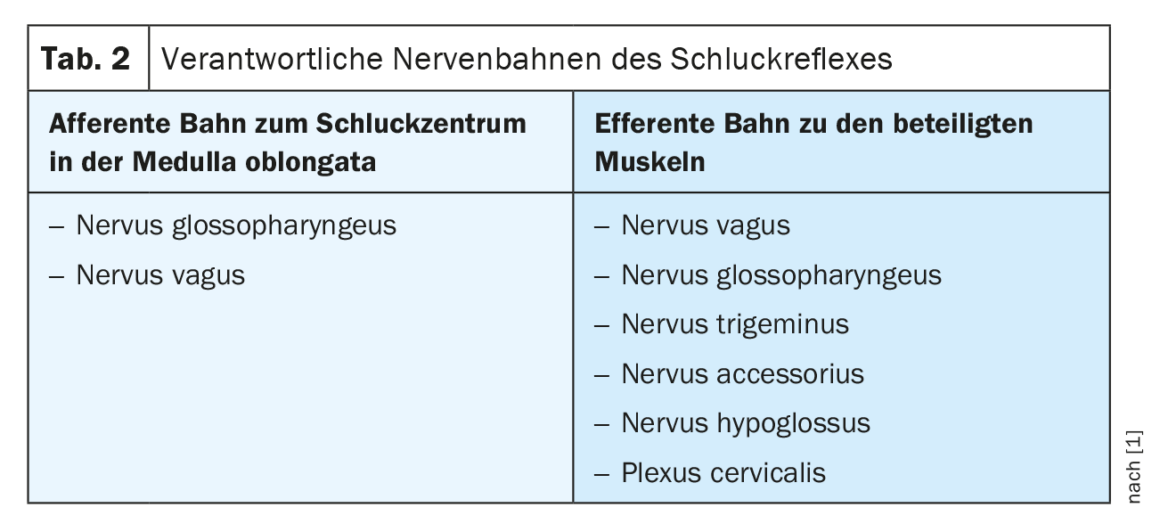

The swallowing reflex is triggered by the food coming into contact with the pharyngeal wall. The responsible afferent and efferent pathways are differentiated in Table 2.

Case study

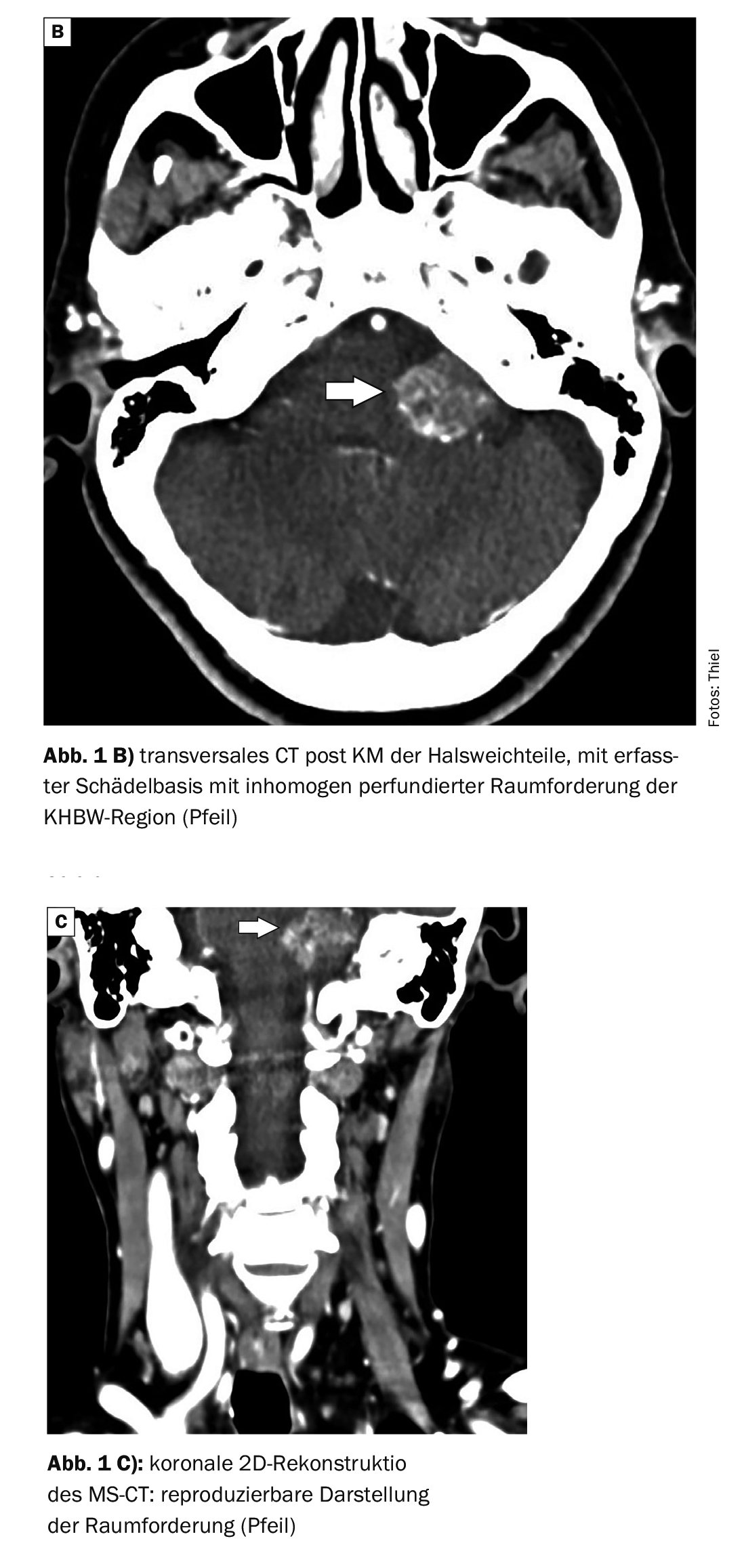

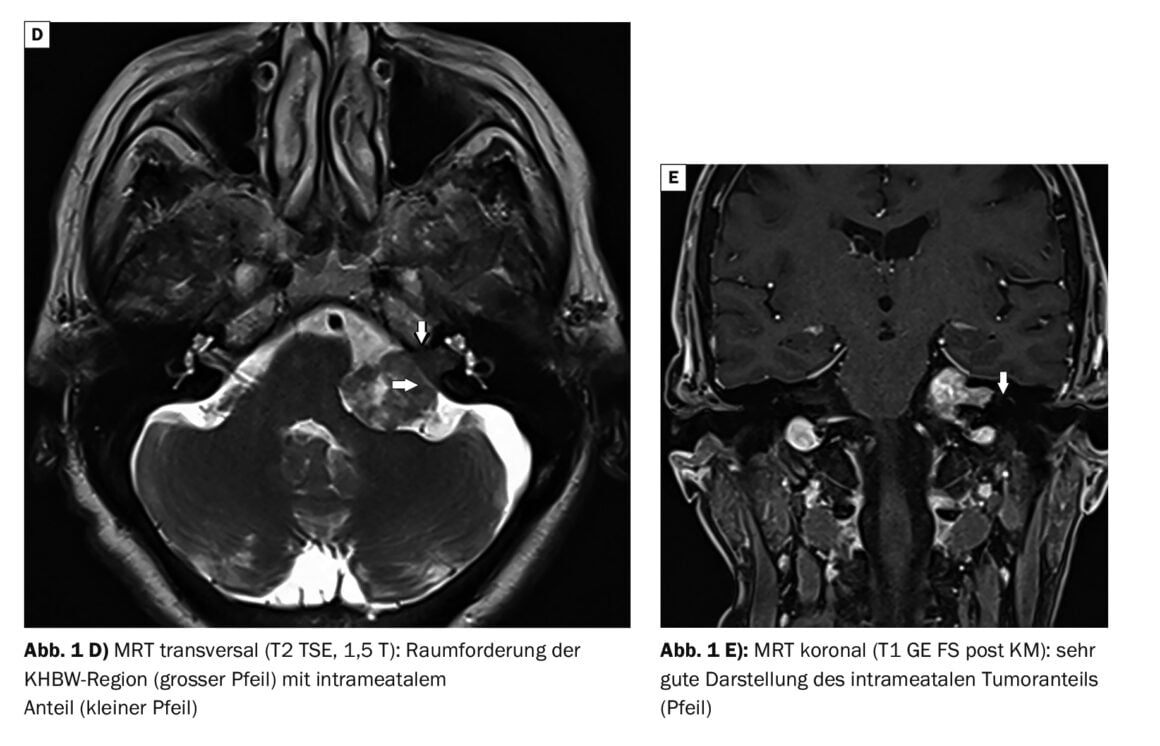

The case study documents the diagnostic imaging process in a 76-year-old female patient with coughing, globus sensation and dysphagia at the initial examination. The ENT examination had not revealed any pathological findings in the oral cavity and hypopharynx, and contrast imaging of the esophagus in the cervical spine area had not shown any relevant pathology (Fig. 1A). Approximately 3 months later, the patient was referred for a CT scan of the soft tissues of the neck (Fig. 1B and C) . These were again unremarkable. However, a pathological finding in the left cerebellopontine angle region (CACA region) was conspicuous. For further clarification, an MRI of the head was performed, which confirmed a large degenerated acoustic neuroma on the left with a voluminous extrameatal and smaller intrameatal part. This resulted in a considerable impression of the brain stem. The fact that there was no significant edema in the brain region suggested a slowly growing mass (Fig. 1D and E).

Acoustic neuroma (AKN) is a benign tumor of the peripheral nervous system [4]. They account for 8% of all intracranial tumors. With usually quite slow growth, the symptomatology appears very late. If the tumors remain small, symptoms of dizziness and hearing loss may not occur. If a slowly increasing hearing loss is noticeable, a hearing test may indicate the change. Typical is a deterioration of the high-frequency range (birdsong is less perceptible). However, a sudden onset of hearing loss is also possible. A very small, intracochlear schwannoma should then also be considered [6]. AKN can also be a possible cause of tinnitus, as well as cause spinning and swaying vertigo accompanied by nausea and/or nystagmus. In very rare cases, large neurinomas may cause cerebrospinal fluid circulation disturbance with pressure increase with headache, neck stiffness, nausea, vomiting, and visual disturbance. Subarachnoid hemorrhages caused by an AKN have been described [3]. In the present case, apart from a persistent swallowing disorder, there was only a slight hearing loss and occasional dizziness, which were previously interpreted as age-appropriate complaints.

Computer tomography examinations are no longer the imaging method of choice for diagnosing acoustic neuromas. The soft tissue contrast is lower than in magnetic resonance imaging. Small AKN can escape CT detection, especially in native diagnostics, while larger masses, as in this case study, can be detected in contrast scans.

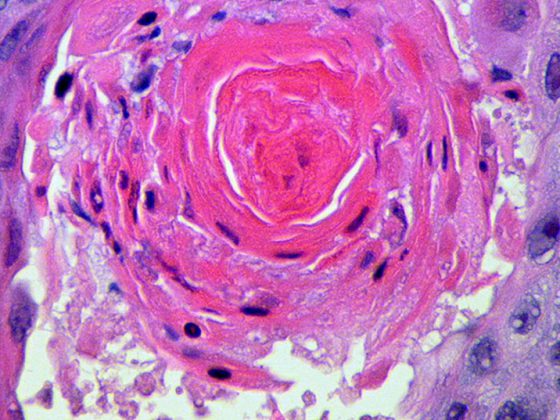

Magnetic resonance imaging is the gold standard of acoustic neuroma imaging. The intravenous application of contrast medium shows a clear increase in signal and often the 2 histological forms (Antoni type A and B) can be differentiated by the regressive changes of type 2 [5,6]. The overall extent with extra- and intrameatal portions is readily assessable. If AKN has only an extrameatal portion (about 20% of cases), differentiation from meningioma may be problematic.

The case study impressively demonstrates the difference in imaging. The MRI shows the exact intrameatal extent of the neurinoma and the regressive changes within the tumor due to the higher soft tissue contrast.

Take-Home-Messages

- Acoustic neuroma is the most common benign intracranial space neoplasm.

- Dysphagia as a symptom can have numerous causes in the upper digestive tract, but can also be the result of a central disorder.

- In addition to lesions of the corticobulbar tracts, space-occupying lesions of the cerebellar bridge-angle region with alteration of the brain stem may be present.

- In diagnostic imaging, MRI with intravenous contrast medium is the standard procedure for detecting these tumors.

Literature:

- “Swallowing act”, https://flexikon.doccheck.com/de/Schluckakt,(last accessed 22.11.2023)

- “Swallowing process”, www.winvitalis.de/ratgeber/ernaehrung-bei-dysphagie,(last accessed 22.11.2023)

- Miller ME, et al.: Intracochlear schwannoma presenting as diffuse cochlear enhancement: diagnostic challanges of rare cause of deafness. Ir J Med Sci 2012; 181(1): 131–134.

- Schwarz R: Akustikusneurinom. [online], www.netdoktor.de, (last accessed 22.11.2023)

- Thiel HJ: Akustikusneurinom. InFo Schmerz & Geriatrie 2021; 3(2): 34–35.

- Uhlenbrock D, Forsting M: MRT und MRA des Kopfes. 2nd, completely revised and expanded edition. Georg Thieme Verlag Stuttgart, New York 2007; pp. 89–91.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023; 18(12): 45–47