Treatment of multiple sclerosis is aimed at reducing relapses, lowering disease activity, and slowing the progression of the disease and increase in disability. Both course and long-term therapy with e.g. immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive drugs can be used for this purpose. But what is indicated and when?

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is not just MS – that is well known. In fact, there certainly seems to be a high proportion of patients with benign courses. A study published last year indicated that after a 30-year follow-up, 40% of those with RRMS were still fully ambulatory (EDSS <3.5) [1]. The study is based on follow-up data of individuals with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS). 80 out of 120 patients developed MS within the observation period. In about one third of the cases, the MS was secondary progressive (SPMS) and all of them had EDSS scores above 3.5 at the end. MS led to premature death in one-fifth of all people with the disease. Because no immunomodulatory therapies were available outside of trials at the time of enrollment, only 11 patients received disease-modifying treatment. This suggests that not all MS takes a malignant course and therefore mild treatment regimens or a wait-and-see strategy may be warranted. Furthermore, in a Swedish cohort study, it was observed that under highly active therapies, the risk of infection in MS patients is increased compared to the normal population [2]. This is due in part to an emerging immunoglobulin deficiency associated with infections that can occur with disease-modifying treatments.

Hit hard and early – the right strategy?

In contrast, a registry analysis concludes that early and intensive therapy can slow the progression of MS disease more than an escalation strategy [3]. For this purpose, an early start of highly active therapy or escalation to higher active treatment in the period up to two years after diagnosis was compared with a later start or escalation four to six years after diagnosis. It was found that the prognosis of MS patients with early onset was better by about one EDSS point after six to ten years of therapy. In addition, studies that have evaluated highly active agents against less active agents demonstrate that immunotherapy is associated with a significantly better outcome [4].

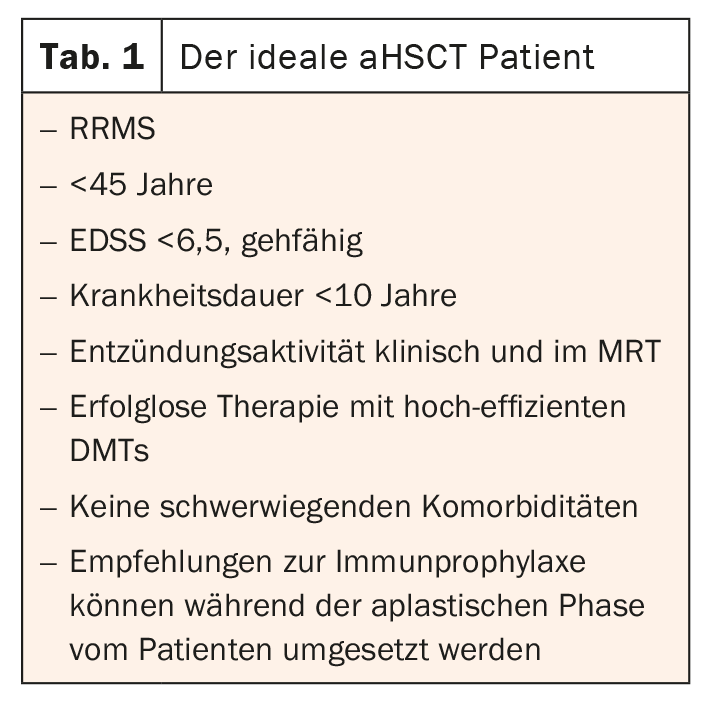

Autologous stem cell transplantation (aHSCT) is available as ultima ratio. However, not all patients are suitable for these. In this case, all other options should be exhausted in advance and the patient should be fully informed (Table 1) [5].

Evidence supports highly effective MS therapy

If the high NEDA rates and improvement in EDSS are taken as a basis, the evidence clearly supports the use of highly effective treatment options from the outset. In the meantime, a better understanding of the possible side effects has also been gained, so that these can be managed well. Nevertheless, the focus should be on comprehensive diagnostics and patients should be selected individually according to the benefit/risk profile.

Literature:

- Chung KK, et al: A 30-Year Clinical and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Observational Study of Multiple Sclerosis and Clinically Isolated Syndromes. Ann Neurol 2020; 87(1): 63-74.

- Luna G, et al: Infection Risks Among Patients With Multiple Sclerosis Treated With Fingolimod, Natalizumab, Rituximab, and Injectable Therapies. JAMA Neurol 2019; 77(2): 184-191.

- He A, et al: Timing of high-efficacy therapy for multiple sclerosis: a retrospective observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2020; 19(4): 307-316.

- Hauser SL, et al: Ofatumumab versus teriflunomide in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 546-557.

- Gavrillaki, et al: Autologous Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in Multiple Sclerosis: Changing Paradigms in the Era of Novel Agents. Stem Cells Int 2019; 5840286.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2021; 19(3): 28.