Ethical conflicts in determining treatment may arise when there are differing views about achievable and reasonable goals of therapy. The first step of an ethically well-founded treatment is to realistically assess the fundamentally achievable therapeutic goals. The second is to involve the patient in the basic considerations of medical scientific evidence in order to define the therapeutic goal that is desirable for the individual patient. Before treatment is initiated, advance care planning should be performed for future decision-making situations in which the patient lacks capacity.

A 77-year-old female patient is admitted to the intensive care unit at night with pneumonia after one cycle of intensive chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. During morning rounds, the attending in charge asks, “How can it be that a patient of this age is given such intensive chemotherapy? And how far should we go here?”

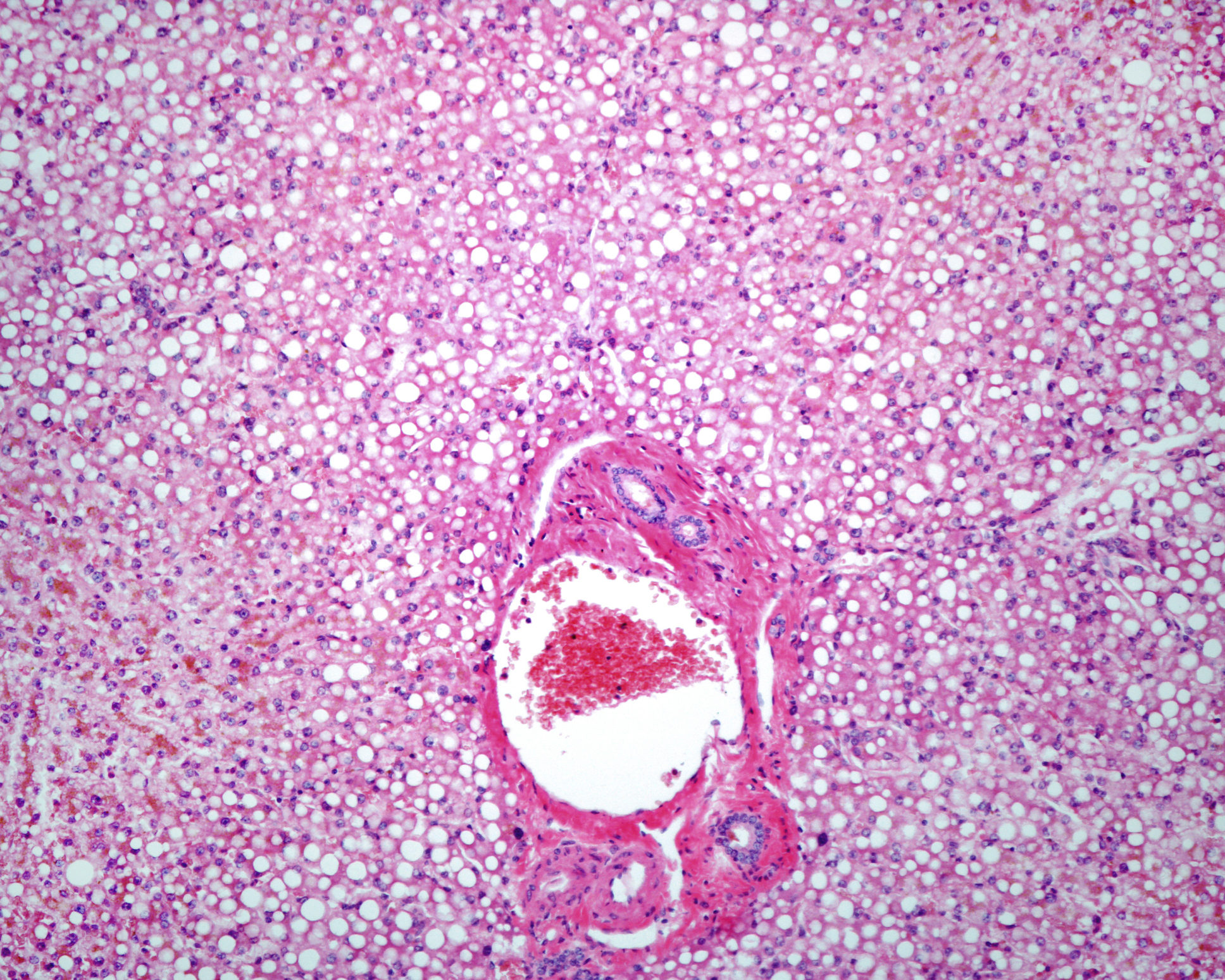

Ethics cannot be separated from medicine. Ethics are at the core of the legitimacy of all health professions. Central ethical questions arise in every treatment of patients: What can, what may, what should I do? Not infrequently, we are dealing with dilemmas, not “win-win” situations: each option not only has different advantages and disadvantages that should be known and communicated and weighted differently for good reasons, but also violates an important principle or goal of medical treatment. You virtually can’t get out of such situations without getting your hands dirty. Contemporary clinical ethics is concerned with, among other things, raising awareness of these issues and supporting patients and treatment teams in such situations. The goal is to find well-reasoned solutions that transparently incorporate the best evidence as well as experience and values (Fig. 1).

At this point, the question of which ethical aspects play a role in the treatment of acute leukemias in advanced age is explored. In this context, the currently much-discussed concept of “Advance Care Planning” is also briefly discussed. It also plays an important role in these disease situations to arrive at a comprehensively well-reasoned treatment plan that reflects the patient’s will.

Different therapy goals

In the central documents describing the nature of medicine, four goals are equally relevant and desirable:

- Avoidance of premature death

- Disease prevention

- Taking care of sick people (Care)

- Relief of suffering [1].

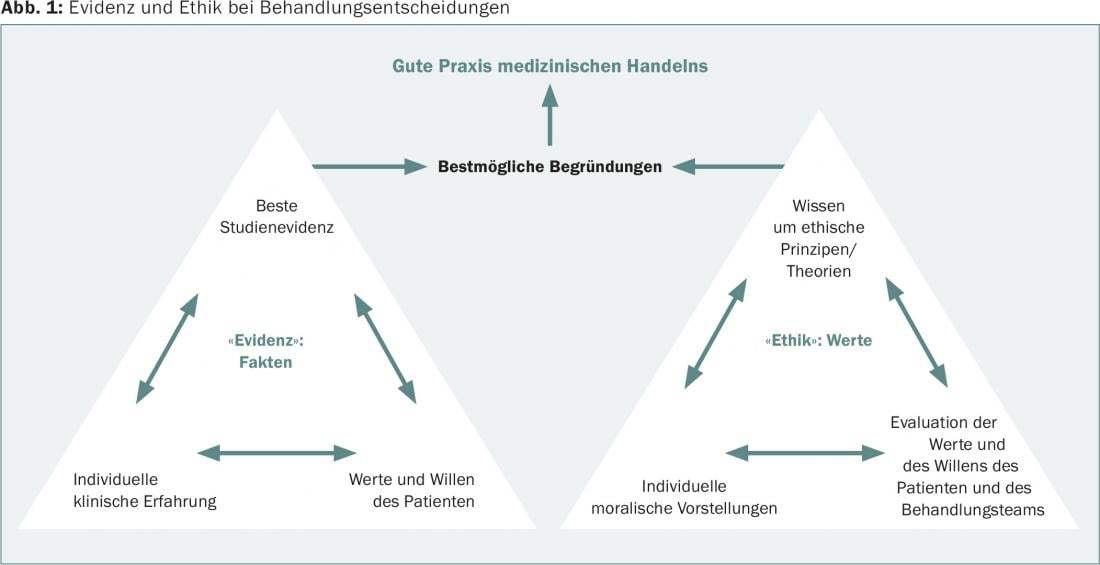

These goals can be further differentiated (tab. 1) . Very often, these goals are passed through one after the other in the course of a disease. However, it is always also about quality of life and often also about quality of death. Ethical conflicts often arise in determining treatment within the treatment team or even between the treatment team and the patient because of differing views on achievable and reasonable treatment goals. It is also not uncommon to think that prolongation of life is always the desirable goal for patients, that failure to achieve this goal means failure of treatment, and that, moreover, alleviation of suffering and prolongation of life are fundamentally mutually exclusive. In most cases, conflicts arise at the transition from the therapeutic goals of “prolonging life with a given disease” to “enhancing/maintaining quality of life” in the stable palliative phase and from primary “symptom control/suffering control” to “enabling a good death” in the unstable palliative phase (“diagnosing dying”). This also applies to the treatment of elderly patients in general and in particular to elderly patients with acute leukemia.

Which goals are achievable?

The first step of an ethically well-founded treatment must be to realistically assess the fundamentally achievable therapeutic goals. Physicians are not required to offer or provide treatment that is not medically appropriate at the patient’s request. However, the question of what constitutes medically futile treatment, for example, where the boundary lies with justifiable life-prolonging treatment, is not trivial and is defined very differently for the same patient groups worldwide [2]. Good clinical ethical practice requires making transparent the professional evaluations and values that are already incorporated into the supposedly objective indication. Hereupon it must be examined whether implemented or proposed measures are also suitable to achieve this goal.

For example, if patients with a tumor are still in a stable palliative situation, it often makes sense to continue blood thinning for atrial fibrillation that has already been started in order to reduce the long-term risk of cerebral strokes and, depending on the tumor, also the tumor-related risk of thrombosis. However, it is not uncommon for patients in the unstable palliative phase, with a clear focus on best possible symptom control, to receive blood thinning for atrial fibrillation that was started ten years ago until shortly before death. It must therefore be continuously examined whether a measure aimed at prolonging life is in principle still suitable for achieving this goal, and whether the associated burdens meet the goal – which becomes increasingly relevant in the course of the disease – of maintaining the best possible quality of life. Similarly, it should be examined whether therapies that are primarily aimed at symptom control achieve this goal as well or better than measures that also serve to prolong life.

Assessment of prognosis, risk and benefit

For elderly patients, an equally differentiated evaluation of the situation must be performed. It is now undisputed that it is not age alone but comorbidities and functional status that determine the prognosis and risk-benefit ratio of medical interventions. For example, the large US registry data on in-hospital resuscitation show that the curve of survival and good-quality survival related to age is U-shaped: patients who are resuscitated at age 18 years have, on average, an equally large or better survival than those who are resuscitated at age 18 years. small chance of 10% like 80-year-old patients to survive resuscitation at all and in a good outcome. This is because young patients who require resuscitation are usually already very ill – and 80-year-olds who are resuscitated despite their advanced age are usually spry beforehand [3,4].

The same differentiation must be made for disease stages in oncological diseases. Patients who require resuscitation in aplasia have only a 0-1% chance of surviving resuscitation; worldwide consensus is that this is futile (“futile”). It would therefore be ethically well justified – but associated with high communication challenges – to discuss not resuscitating in the very rare case of cardiac arrest under aplasia, despite intensive chemotherapy clearly aimed at prolonging life or even cure. Patients with solid tumors have a better chance of survival than patients with hematologic diseases. The outcome of resuscitation for cancer is not determined by metastasis but by the Karnofsky index. If this is still above 50, the chance of surviving resuscitation is almost the normal average (15% in all patients after resuscitation); if the Karnofsky index is below 50, the chance drops to below 5% [5].

“Informed consent” or “shared decision making”.

The second step of an ethically well-founded treatment is to involve the patient – as far as possible and desired by the patient – in the basic considerations of medical-scientific evidence and experience described above, in order to define the therapeutic goal that is desirable for the individual patient. Not everyone over 80 years of age has a poor quality of life, and not everyone under 60 years of age wants to be resuscitated with good knowledge of the risks and benefits of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

In this respect, the minimal “informed consent” standard differs fundamentally from the “shared decision making” standard widely advocated today as the gold standard of decision making with patients. In the case of “informed consent”, the physician (or the tumor board) carries out the risk-benefit evaluations alone and communicates a treatment recommendation or even a decision to the patient without actually making the considerations made transparent, and the patient can only agree or reject this option. Shared decision making involves the patient in these risk-benefit considerations, often supported by evidence-based decision support and specific communication skills [6–8]. Such decision aids, which are subject to high quality standards, have now been developed for several 100 disease situations, for example, for weighing whether or not to resuscitate, for many screening and diagnostic procedures (e.g., PSA test, mammography screening), and also for therapeutic options (e.g., anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation, treatment procedures for breast or colorectal cancer, chemotherapies for hematologic diseases) [8].

Treatment decisions in elderly patients with acute leukemias.

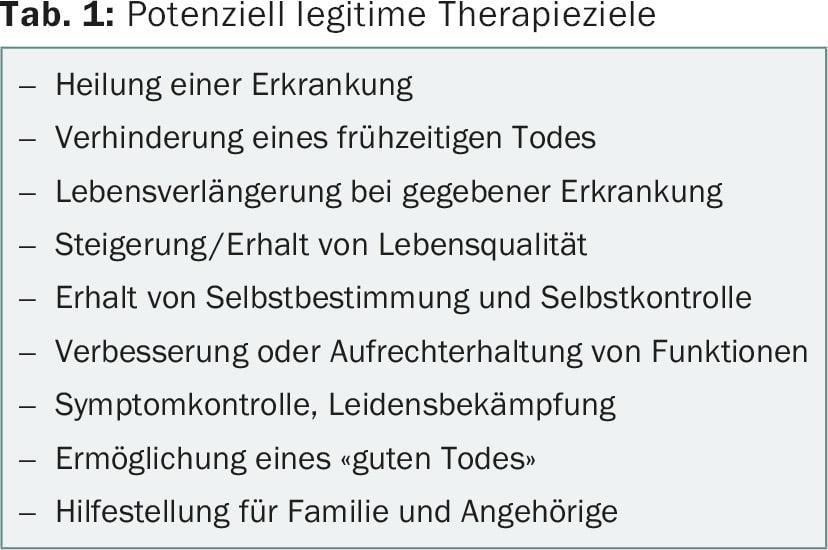

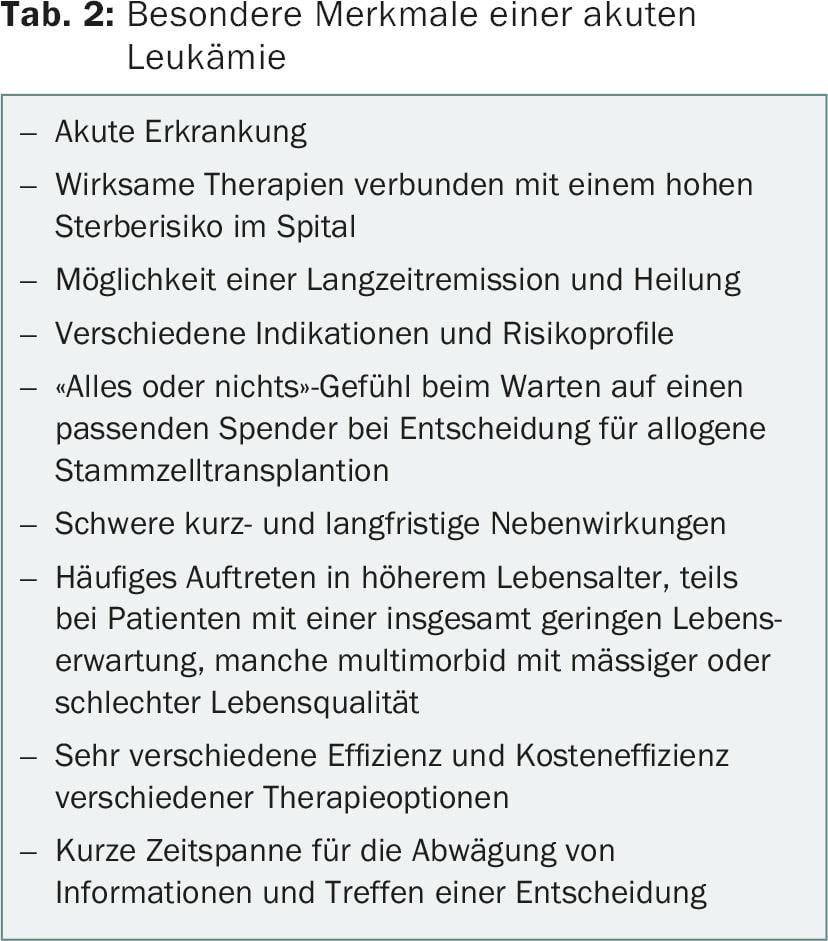

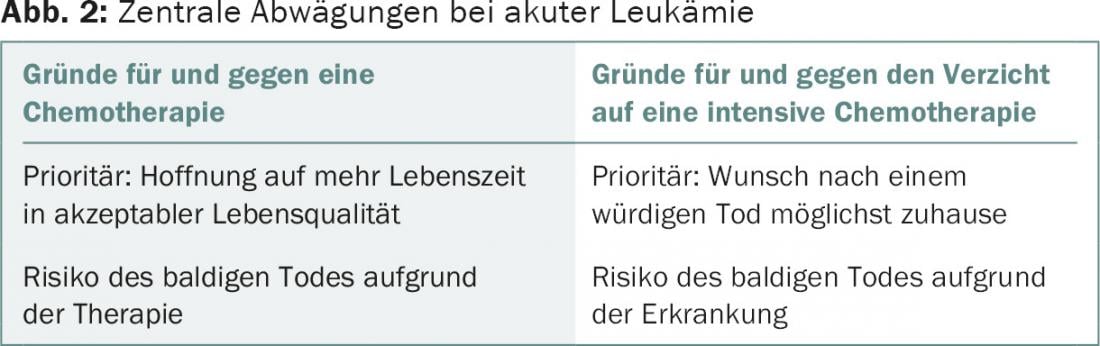

To date, to the author’s knowledge, there are no evidence-based decision aids for acute leukemias in elderly patients. However, the essential aspects from a clinical-ethical perspective initially correspond to the basic considerations described. Evidence and expert opinion on the benefits of intensive chemotherapy in acute leukemia in elderly patients differ, especially for the key therapeutic goals of quality of life and prolongation of life. Some authors see a benefit, others doubt this [9,10]. The landmark study by Temel et al. basically showed that early integration of palliative care can significantly prolong life [11,12]. However, according to the analyses of the Swedish registry, elderly patients also benefit from intensive chemotherapy (versus primarily palliative therapies) in terms of quality of life [9]. Overall, disease-specific features must be considered (Table 2), which require key trade-offs (Fig. 2).

In an elderly patient with acute leukemia, it is essential in treatment planning that the primary desirable treatment goal for the patient is elicited (based on achievable treatment goals, specific risk profile, and overall clinical situation, especially comorbidities and functional status). Not infrequently, after careful consideration and involvement of the patient, it turns out that the priority goal is a death at home that is accompanied as well as possible, since the patient ultimately feels that life has been lived. In such a situation, it makes sense to forgo intensive chemotherapy because the risk of dying in the hospital is quite high. If quality of life is considered high and the chance to live longer is prioritized, intensive chemotherapy – adapted to the individual risk profile – should be considered.

Advance Care Planning

In either case, plan well ahead for what will happen if health deteriorates. If the patient decides on the therapeutic goal of primary best palliation, it must be well evaluated where this can take place. If the patient wants to die at home, a complex palliative care plan with intensive involvement of outpatient services is needed. In the case of the decision for the goal of life extension, planning must also be made for situations in which this “Plan A” does not materialize. Before treatment is initiated, it is imperative that resuscitation under aplasia and the individual limitations of life-prolonging treatment, among other issues, be intensively discussed.

This advance care planning is defined as a planning and implementation process for health-related decision-making situations in the future in which patients are not capable of making judgments. Central reference persons and representatives of the entire treatment chain are involved in the process: family doctor, nursing staff in outpatient care, paramedics, emergency physicians, specialists in inpatient care. The patient should be supported in formulating an advance directive that makes medical sense and is tailored to him or her, and in drawing up emergency plans adapted to his or her values. This concept, which is becoming increasingly established in oncology worldwide [13–15], and which is also integrated into the evidence-based S3 Palliative Care Guideline, is also being evaluated at the University Hospital Zurich in cooperation with the Clinics of Hematology and Oncology as part of a study funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation [16].

Advance Care Planning completes a clinically and ethically well-founded treatment plan for the therapy of acute leukemias in elderly patients. Advance care planning would contribute to the fact that in the case described at the beginning, the senior physician in charge would also know with greater certainty whether the treatment of the pneumonia in the 77-year-old patient would be in her best interest or whether a change to a comfort care situation should be made.

Literature:

- Cassel EJ: N Engl J Med 1982; 306: 639-645.

- Bagheri A, (ed.): Medical futility: A cross-national study. Imperial College Press: London, 2014.

- Larkin GL, et al: Resuscitation 2010; 81: 302-311.

- Levy PD, et al: Circ Heart Fail 2009; 2: 572-581.

- Myrianthefs P, et al: J of BUON 2010; 15: 25-28.

- Stiggelbout AM, et al: BMJ 2012; 344: e256.

- Krones T: Patient and treatment/care team relationships and shared decision making. In Marckmann G (ed.): Praxishandbuch Ethik in der Medizin. Medizinisch-Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, Berlin (in press).

- Stacey D, et al: Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 1: CD001431.

- Juliusson G: Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2011; 11 Suppl 1: S54-59.

- Kantarjian H, et al: Blood 2010; 116: 4422-4429.

- Temel JS, et al: N Engl J Med 2010; 363(8): 733-742.

- Davis MP, et al: Ann Palliat Med 2015; 4(3): 99-121.

- Marckmann G, In der Schmitten J: Zschr Med Ethics 2014; 59: 213-227.

- Butler M, et al: Ann Intern Med 2014; 161: 408-418.

- S3 Guideline, Palliative Care for Patients with Noncurable Cancer. May 2015 AWMF Registry Number: 128/001OL.

- MAPS Trial: www.nfp67.ch/D/projekte/entscheidungen-motive-haltungen/planung-des-lebensendes/Seiten/default.aspx.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2015; 14(5): 14-17.