Young adults are rarely affected by adrenal incidentalomas; the average age is over 50. The majority are endocrinologically inactive adrenal adenomas, in about 10-15% of cases the incidentalomas are hormonally active and malignant tumors are found in about 2-5% of cases. A step-by-step approach is recommended for clarification.

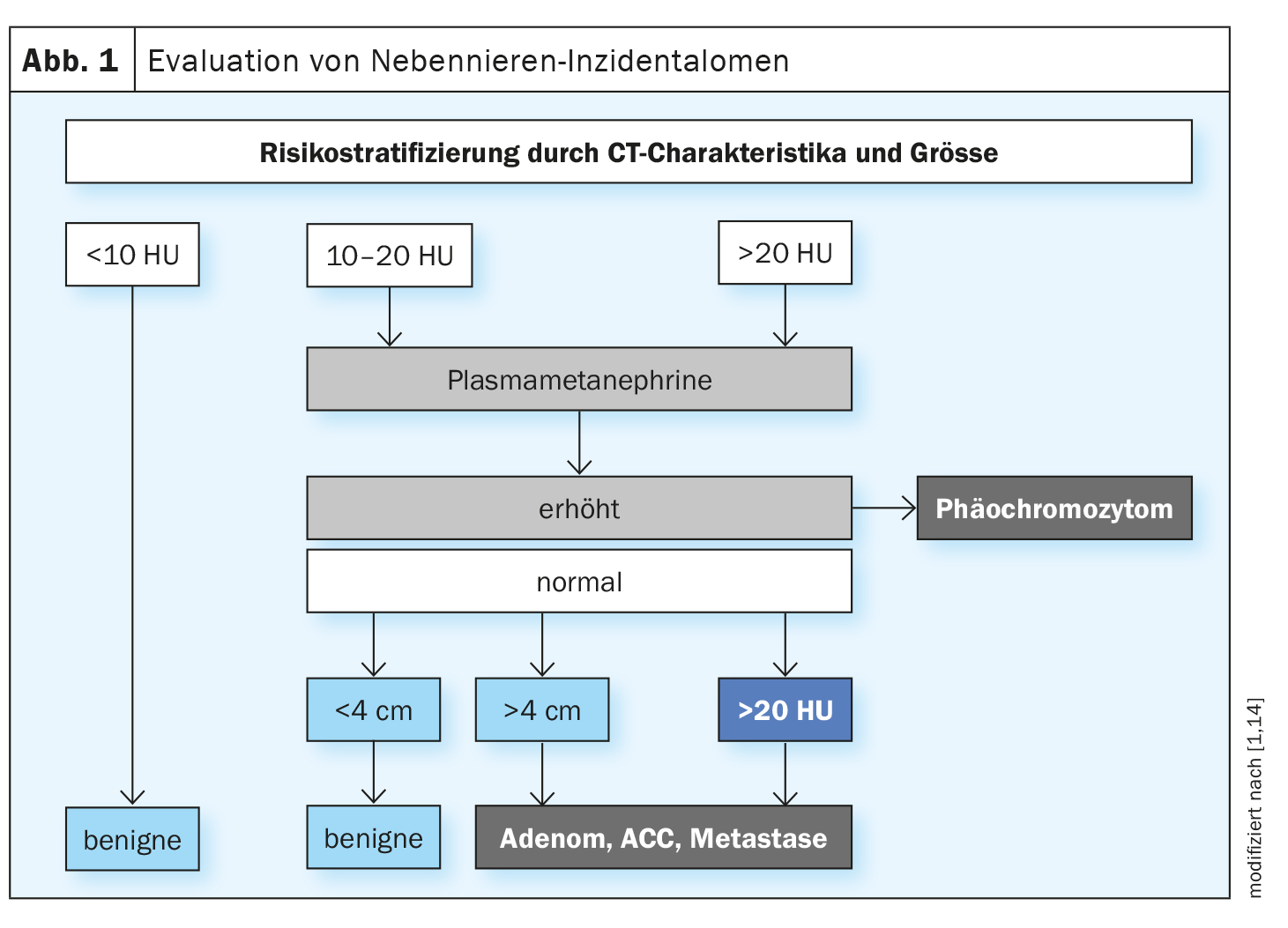

Referring to the current data situation and the practice guidelines of the European Society of Endocrinology, Prof. Dr. med. Michael Brändle, Chief Physician, General Internal Medicine/Hospital Medicine and Emergency Medicine at the Cantonal Hospital of St. Gallen, explained the recommended clarification algorithm (Fig. 1) [1,2]. An adrenal incidentaloma is an adrenal mass of at least 1 cm in size detected by imaging if it is an incidental finding in the context of diagnostic imaging that was not performed due to a suspected adrenal disease or staging examination for a known malignant tumor. The focus is on the question of whether the findings are pathological or not.

In this context, the following two points need to be clarified first and foremost [1,2]:

- Does the incidentaloma produce hormones in excess?

- Is there a malignancy? (classic example: adrenocortical carcinoma).

Epidemiological data show that, in parallel with the increase in imaging examinations, more and more small, benign lesions are being detected in older patients. Adrenal incidentalomas are extremely rare in people under the age of 30; the average age is 54 [3,4]. The incidence of large and malignant tumors remained the same during the study period 1995-2015 [5]. 71.2-82.4% of adrenal incidentalomas are benign and hormonally inactive (adenomas) [6].

Endocrine active incidentaloma?

The speaker recommended first taking a medical history and performing a physical examination, as this would simplify the interpretation of the laboratory findings [1]. Endocrine active adrenal tumors can be one of the following clinical pictures (Table 1) :

- Hypercortisolism (Cushing’s syndrome)

- Pheochromocytoma

- Hyperaldosteronism (Conn’s syndrome)

- Sex hormone excess (extremely rare)

The first step is to clarify whether a pheochromocytoma could be present. Pheochromocytomas are often clinically silent or oligosymptomatic. Possible non-specific symptoms are headache (60-90%), sweating (55-75%), pallor, flushing, restlessness, weight loss, fatigue and leukocytosis [13]. The symptoms are based on an increased concentration and thus increased effect of the released catecholamines. “You should always look for a pheochromocytoma – even in normotensive patients,” emphasized Prof. Brändle. A pheochromocytoma is rather unlikely in small lesions with an adenoma-typical signal. The guidelines recommend the measurement of free metanephrines in plasma or fractionated metanephrines in the urine collection to rule out a pheochromocytoma [2,7]. There are certain pitfalls in the determination of metanephrines, said the speaker, explaining that the results can be false-positive in patients who are being treated with paracetamol or tricyclic antidepressants.

The next point of clarification concerns hyperaldosteronism. However, “case detection” is proposed for this purpose, i.e. only looking for it in certain subgroups of patients [8]. These include patients with arterial hypertension or unexplained hypokalemia. Determination of the aldosterone/renin ratio is suggested as a screening test, although various medications (e.g. hypertensives) can lead to a distortion, so that a change in therapy may be necessary beforehand. Drugs that can influence the aldosterone/renin ratio:

- false positive results: Beta-blockers

- false negative results: ACE inhibitors, diuretics, AT1 antagonists, mineraloceptor antagonists

Calcium blockers, alpha-blockers and vasodilators have little influence on the results. It is recommended that medications that can lead to a distortion of the test result be discontinued 1-4 weeks before testing [9].

| Follow-up check required? |

| Benign, non-secretory incidentalomas: Follow-up only for new aspects |

| Imaging of intermediate suspicious findings (if an adrenalectomy has not yet been performed): Check-up after 6-12 months; surgery is indicated if the size increases >20% per 5 mm |

| Mild autonomous cortisol secretion: Regularly check comorbidities |

The next step is to clarify whether hypercortisolism is present. A manifest cortisol excess can be seen in the patients, as they exhibit characteristics of a typical Cushing’s habitus, reported Prof. Brändle [1]. Cushing’s syndrome is a metabolic disorder caused by an excess of glucocorticoids such as cortisol. There are exogenous (e.g. long-term therapy with glucocorticoids) and endogenous causes [13]. Treatment depends on the cause of Cushing’s syndrome; adenomas of the pituitary gland or adrenal glands can be surgically removed. A suspected Cushing’s syndrome can be verified or falsified with the 1 mg dexamethasone test [2]. The guideline recommendations are that a dexamethasone inhibition test should be performed on all patients [2]. Serum cortisol levels ≤50 nmol/l (≤1.8 μg/dl) are considered the cut-off for ruling out autonomous cortisol excretion. If the values are in the range 51-138 nmol/l, repeated testing should be considered depending on the presence of comorbidities. Values >138 nmol/l are classified as autonomous cortisol secretion. In the presence of comorbidities such as diabetes or hypertension, consideration should be given to whether patients might benefit from surgery (adrenalectomy). A meta-analysis shows that adrenalectomy can lead to an improvement in pre-existing hypertension and diabetes, while no significant change was found with regard to dyspilipdemia and obesity [10]. Bancos et al. included 26 studies in their analysis with data from 584 patients with subclinical Cushing’s syndrome and 457 patients with asymptomatic adrenal tumors [10].

As a result, adrenalectomized patients with subclinical Cushing’s syndrome showed statistically demonstrable improvements in hypertension (RR 11; 95% CI: 4.3-27.8) and diabetes mellitus (RR 3.9; 95% CI: 1.5-9.9) compared to conventional care [10]. Hypertension improved in 21 of 54 adrenalectomized patients with asymptomatic adrenal tumors.

Dignity: benign or malignant?

The risk of malignancy increases with increasing tumor size: for incidentalomas >6 cm the risk of malignancy is 25%, for 4-6 cm it is 6% and for <4 cm it is only 2% [11,12]. Native computed tomography (CT) without contrast is the best validated method for assessing dignity. According to the current guidelines of the European Society of Endocrinology, the adrenal mass can be classified as benign if the Hounsfield Units (HU) are ≤10. If the size of the incidentaloma is <4 cm, no further imaging is necessary in most cases, according to the speaker.

Surgery should be considered for benign, non-secretory incidentalomas (<4 cm, ≤10 HU) ist eine Nachuntersuchung nur bei neuen klinisch relevanten Aspekten erforderlich. Bei suspekten Befunden (10–20 HU) empfahl Prof. Brändle eine Verlaufskontrolle nach 6–12 Monaten; bei Grössenzunahme>20% per 5 mm). In patients with mild autonomous cortisol secretion, regular assessment of comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, etc.) is advisable [2,13].

Congress: Davos Medical Forum

Literature:

- “Adrenal Incidentaloma”, Prof. Dr. med. M. Brändle, 31st Medical Forum, Davos, 05.03.2024.

- Fassnacht M, et al: Management of adrenal incidentalomas: European Society of Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline in collaboration with the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors. Eur J Endocrinol 2016; 175(2): G1-G34.

- Sherlock M, et al: Adrenal incidentaloma. Endocr Rev 2020; 41(6): 775-820.

- Jing Y, et al: Prevalence and Characteristics of Adrenal Tumors in an Unselected Screening Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. Ann Intern Med 2022; 175(10): 1383-1391.

- Ebbehoj A, et al: Epidemiology of adrenal tumors in Olmsted County, Minnesota, USA: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2020; 8(11): 894-902.

- Hanna FWF, et al: Management of incidental adrenal tumors. BMJ 2018; 360: j5674.

- Lenders JWM, et al: Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2014; 99 (6): 1915-1942.

- Funder et al. The Management of Primary Aldosteronism: Case detection, diagnosis and treatment: and endocrine society clinical practice guideline. U Clin Endocrin Metab 2016; 101: 1889-1916.

- German Conn Register, www.conn-register.de,(last accessed 05.04.2024)

- Bancos I, et al: Therapy of Endocrine Disease: Improvement of cardiovascular risk factors after adrenalectomy in patients with adrenal tumors and subclinical Cushing’s syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol 2016; 175(6): R283-R295.

- Mantero F, et al: A survey on adrenal incidentaloma in Italy. Study Group on Adrenal Tumors of the Italian Society of Endocrinology. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000; 85(2):637-644.

- Kebebew E: Adrenal Incidentaloma. N Engl J Med 2021; 384(16): 1542-1551.

- Elhassan YS, et al: Natural History of Adrenal Incidentalomas With and Without Mild Autonomous Cortisol Excess: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2019; 171(2): 107-116.

- Bancos I, Prete A: Approach to the patient with adrenal incidentaloma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021; 106(11): 3331-3353.

- “Pheochromocytoma”, https://flexikon.doccheck.com,(last accessed 08.04.2024)

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2024; 19(4): 39-41 (published on 18.4.24, ahead of print)