The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) is

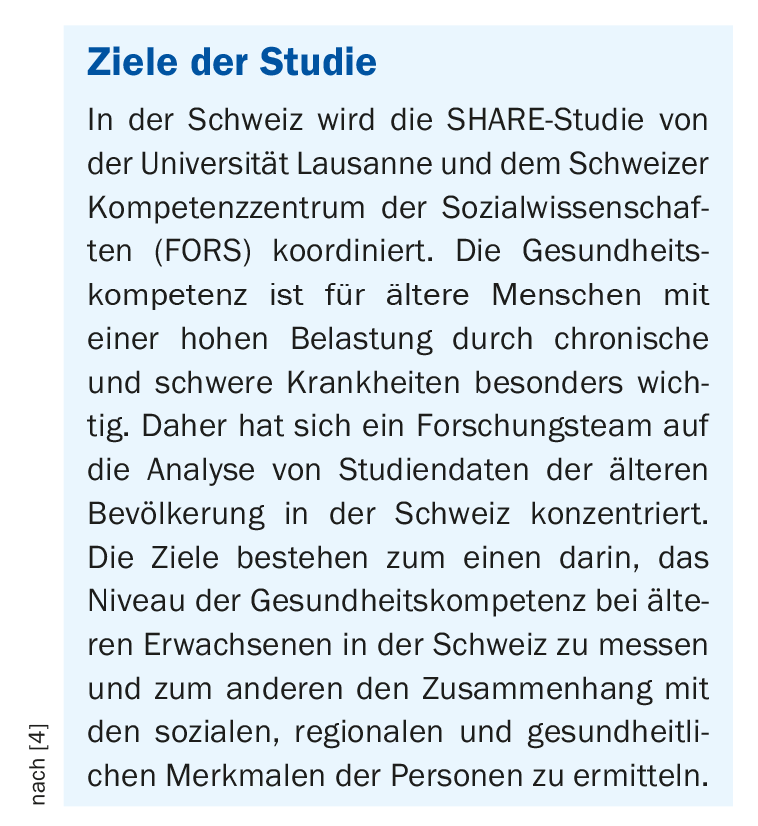

one of the largest European surveys conducted with people aged 50 and over. Twenty countries are involved in the study, including Switzerland. Researchers at the University of Lausanne analyzed the dataset in terms of health literacy in the 58-75+ age group, among other factors.

Health literacy is considered an important skill for maintaining health and coping with disease in modern information societies [1]. According to Santana et al. 2021 Health literacy is “the extent to which people are able to find, understand, and use information and services to make health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others” [2]. Health literacy influences the way people perceive their health problems, communicate with health professionals, and make medical decisions [3]. In health literacy, four steps of information processing can be distinguished: Finding, understanding, assessing, and applying information [6]. In addition to the four steps of information processing, the following three areas of health literacy can be distinguished: Disease management, disease prevention, and health promotion.

Health literacy skills are very important for older people

When it comes to health, the population faces numerous challenges [6]. Digital transformation is permeating not only the lives and health of every individual, but the entire healthcare system. This increasingly requires everyone to take an active role and responsibility for their own health and that of others. In addition, many are concerned about more self-determination and co-determination on this issue. In order to be able to perform the associated tasks and deal adequately with health information, every individual needs sufficient health literacy.

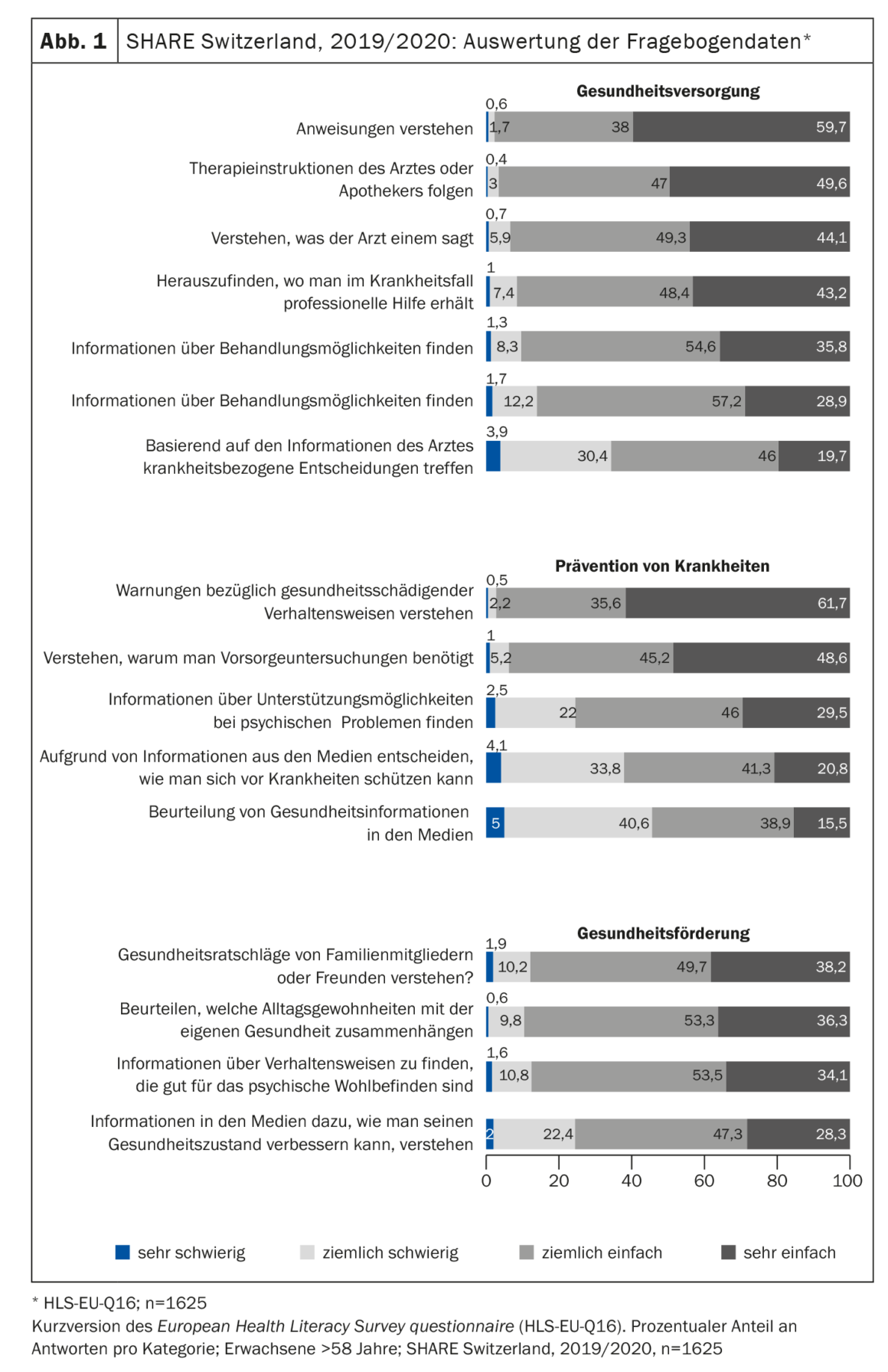

At an older age, people are more likely to be affected by chronic diseases and health restrictions in general, so that health literacy has a special relevance. The international Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) is a multidisciplinary longitudinal survey of people over 50 in Europe. The short version of the European Health Literacy Survey (HLS-EU-Q16) was used to assess health literacy [4,5]. This questionnaire measures a person’s subjectively assessed difficulty in coping with health-related information tasks and demands, in the areas of health care, prevention of diseases, and health promotion [6] (Fig. 1).

Survey wave SHARE 2019/2020 Switzerland

To analyze health literacy and its association with certain personal characteristics of older adults in Switzerland, data from 1625 participants in the SHARE 2019/2020 survey wave here were used. Three age groups (58-64 years, 65-74 years, 75+ years) were formed. The proportion of women in the sample was 50%, the mean age was 73.4 years (SD: 8.5), and the majority of respondents were between 58 and 64 years old. Nearly three-quarters of respondents had a partner, and 63% had a secondary school diploma. 70% of the study participants resided in German-speaking Switzerland and 59% in a rural area. Most respondents were healthy according to self-report, with only 16% reporting “poor” or only “fairly” good health.

The survey results at a glance

Figure 1 shows the weighted proportion of responses for each item surveyed on the HLS-EU-Q16, grouped by health domain [4].

Health Care: Overall, fewer than 35% of respondents rated any of the seven health care items as very or somewhat difficult. Only 2.3% (0.6% = “very difficult,” 1.7% = “quite difficult”) reported difficulty understanding doctors’ or pharmacists’ instructions about taking a prescribed medication, 3.4% reported difficulty following doctors’ or pharmacists’ instructions, 6.6% understanding what doctors say, 8,4%, finding out where to get professional help when sick, 9.6%, finding information about treatments for illnesses that affect the person, 13.9%, using the doctor’s information to make decisions, and 34.3%, judging when it is necessary to get a second opinion from another doctor.

Prevention of Illness: Less than 46% of respondents reported difficulty with any of the five disease prevention items. The percentage of those who rated it “very difficult” or “quite difficult” to understand health warnings about behaviors such as smoking, physical inactivity, and excessive alcohol consumption was 2.7%. Difficulty understanding the need for screening was reported by 6.2%. With a share of 24.5%, a comparatively large number of study participants expressed difficulties in finding information on how to deal with mental health problems such as stress or depression. 37.9% find it difficult to deduce how to protect themselves from disease from information in the media, and 45.6% said they find it difficult to judge whether information about health risks in the media is reliable.

Health promotion: less than 25% found it “very difficult” or “quite difficult” to address different types of issues/aspects related to health promotion. A minority of 10.4% of respondents had difficulty assessing which everyday behaviors were related to their own health, 12.1% had difficulty understanding health advice from family members or friends, 12.4% had difficulty learning about activities beneficial to mental well-being, and 24.4% had difficulty understanding information about healthy lifestyles in the media.

Conclusions and outlook

Multivariable analyses showed that lower health literacy correlated with the following characteristics: male gender, low education level, difficulty making a living, poor self-rated health. Most older adults in Switzerland found it easy to navigate the health care system and use appropriate health-related information. The health-related aspects where respondents perceived more difficulties were: dealing with mental health problems, getting a second opinion from another doctor, protecting themselves from illness based on information in the media, assessing the reliability of information about health risks in the media, and understanding information about how to positively influence their health status.

The “gender gap” may be due to women’s traditional role as caregivers, which is still relevant today and contributes to women acquiring more health-related knowledge and skills [7]. The positive correlation between educational attainment and health literacy is not surprising in that education promotes the skills measured in the health literacy scale [8]. For older adults, maintaining and developing adequate levels of health literacy depend mainly on whether or not they engage in lifelong learning activities such as formal education, reading practice, Internet use, and social or volunteer activities [4].

Previous research has shown that providing health information is often insufficient to improve health literacy [4]. Depending on the situation, assistance is needed on how to reduce stressful situations and strengthen protective factors. The fields of action for the promotion of health literacy of people in difficult life situations include, in addition to rapid support in emergency situations, providing orientation and perspectives, support in dealing with the authorities, help in establishing/maintaining supportive relationships, and promotion of media literacy [9].

Literature:

- Jordan S, Hoebel: Health literacy of adults in Germany. Federal Healthbl 2015; 58: 942-950.

- Santana S, et al: Updating Health Literacy for Healthy People 2030: Defining Its Importance for a New Decade in Public Health. J Public Health Manag Pract 2021; 27 Suppl 6: S258-264.

- Ladin K, et al: End-of-Life Care? I’m Not Going to Worry About That Yet. Health Literacy Gaps and End-of-Life Planning Among Elderly Dialysis Patients. Gerontologist 2018; 58(2): 290-299.

- Meier, et al: Health literacy among older adults in Switzerland: cross-sectional evidence from a nationally representative population-based observational study. Swiss Med Wkly 2022; 152: w30158.

- Sørensen K, et al: Measuring health literacy in populations: Illuminating the design and development process of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q) BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 948.

- De Gani SM, et al: Health Literacy Survey Switzerland 2019-2021, Final Report, Sep 14, 2021.

- Colombo F, et al: Help Wanted: Providing and Paying for Long-Term care [Internet]. OECD; 2011,

www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/help-wanted_9789264097759-en,(last accessed Jan. 15, 2023) - Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, Doyle G, Pelikan J, et al; (HLS-EU) Consortium Health Literacy Project European. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012; 12(1): 80.

- Wieber F, et al: Health literacy in challenging contexts. Final Report, ZHAW, 02/2022.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023; 18(1): 36-37

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2023; 21(1): 38-39.