For some years now, medical research has been increasingly concerned with herbal medicines with analgesic and antiphlogistic potential. And certainly the disillusionment with COX-2 inhibitors has contributed to the fact that today extracts of willow bark and devil’s claw are increasingly used again.

Willow bark

Willow, Salix, is the oldest medicinal plant in Western medicine, along with opium, with an analgesic and antiphlogistic effect. Acetylsalicylic acid, or Aspirin®, was derived from one of its ingredients, the glycoside salicin or salicylic acid, the aglycone of salicin.

The efficacy of standardized extracts of willow bark has been documented for the following complaints:

- Cox and gonarthrosis [1, 2]

- Acute back pain [3]

- Exacerbations of chronic back pain [4].

March and Kemperer attribute the effect to inhibition of TNF-alpha, IL-6 as well as PGE2 [5]. These authors, as well as Khayyal et al. [6] indicate that willow bark extract is more effective than an equivalent amount of salicin or an adequate amount of acetylsalicylic acid alone. Khayyal et al. concluded that other ingredients of the willow bark extract are also involved in the effect.

Rosehip

While willow bark extracts could be registered as a drug in Switzerland on the basis of these results, one of them even with approval for basic insurance, preparations from rosehip (Rosa canina) never received drug registration. Although some in vivo [7] and clinical studies [8–10] have been published demonstrating efficacy of rosehip preparations in osteoarthritis. However, the rosehip could not establish itself as a medicinal plant.

Devil’s claw

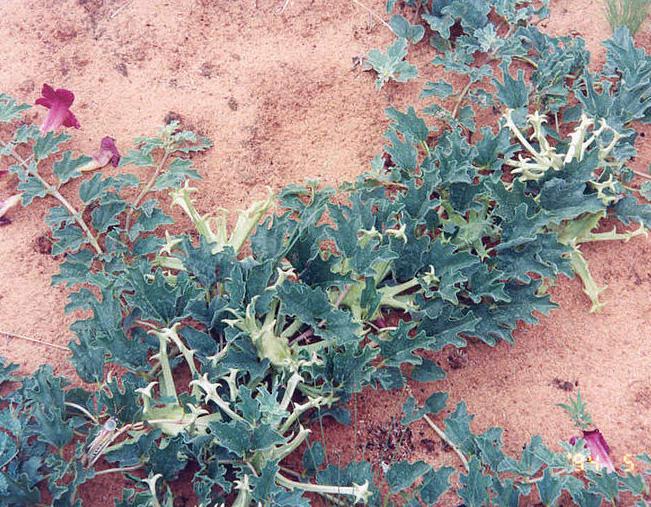

Recently, research attention has focused on devil’s claw, Harpagophytum procumbens, a medicinal plant from southern Africa that has been used by indigenous people for centuries to treat pain and gastrointestinal complaints. The plant gets its name from the woody fruits and arm-like outgrowths.

Pharmacological studies showed suppression of TNF-Kappa-B [11, 12] or TNF-Alpha [13] and thus inhibition of NO and COX-2.

Devil’s claw for osteoarthritis

Various clinical studies demonstrate the efficacy of Harpagophytum preparations in osteoarthritis. Hydro-alcoholic extracts with a daily dosage of 50-100 mg of harpagoside [14] were found to be the most effective.

Chantre et al. demonstrated in a comparative study published in 2000 [15] that in patients with osteoarthritis of the hips and knee, a devil’s claw preparation was as effective as diacerein after four months of treatment.

Warnock et al. In 2007, [16] demonstrated that 60% of subjects with osteoarthritis were able to either completely discontinue or reduce concomitant analgesics after treatment with a devil’s claw preparation.

In 2007, a meta-analysis appeared [17], which confirmed the analgesic and antiphlogistic efficacy, especially in arthritic complaints, of standardized devil’s claw preparations.

Devil’s claw (Harpagophytum procumbens) from southern Africa

Harpagophytum safety

A review published in 2008 [18] examined the safety of Harpagophytum procumbens using 28 clinical trials. None of these studies showed a greater incidence of adverse effects in the devil’s claw groups than in the corresponding placebo groups. Also, devil’s claw preparations do not exhibit the typical side effects of synthetic NSAIDs.

Facts

Rosehip (Rosa canina)

- Uncertain effect on musculoskeletal complaints. Not a registered preparation.

Willow (Salix species)

- Documented effect in various inflammatory complaints.

- A registered preparation in the basic insurance (Assalix®).

Devil’s Claw (Harpagophytum procumbens)

- Well documented effect in inflammatory complaints. Various registered preparations, two of which are covered by basic insurance (Harpagomed®, Harpagophyt® Mepha).

Conclusion

Standardized preparations from willow bark and devil’s claw are in many cases valid alternatives to synthetic analgesics and anti-inflammatories or effective supplements for musculoskeletal complaints, especially osteoarthritis. They are characterized by good efficacy and safety.

Literature:

- Schmid B: Treatment of Cox’s and gonarthrosis with a dry extract of Salix purpurea × daphnoides, placebo-controlled double-blind study of kinetics, efficacy, and tolerability of willow bark. Eberhard Karls University 1998.

- Schmid B, et al: Efficacy and tolerability of a standardized willow bark extract in osteoarthritis patients: Randomized, placebo-controlled double-blind study. Z Rheumatologie 2000; 59: 314-320.

- Chrubasik S, et al: Potential economic impact of using a proprietary willow bark extract in outpatient treatment of low back pain: an open non-randomised study. Phytomedicine 2001; 8: 241-251.

- Chrubasik S, et al: Treatment of low back pain exacerbations with willow bark extract: A randomized double-blind study, Am J Med 2000; 109: 9-14.

- March RW, Kemper F: Willow bark extract – effects and efficacy. State of knowledge on pharmacology, toxicology and clinic, Wien Med Wschr 2002; 152: 354-359.

- Khayyal MT, et al: Mechanisms involved in the anti-inflammatory effect of a standardized willow bark extract. Drug Research 2005(11); 55; 677-687.

- Lattanzio F, et al: In vivo anti-inflammatory effect of Rosa canina L. extract. J Ethnopharmacol 2011(1); 137: 880-885.

- Rein E, et al: A herbal remedy, Hyben Vital (stand. Powder of a subspecies of Rosa canina fruits), reduces pain and improves general wellbeing in patients with osteoarthritis – a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial. Phytomedicine 2004; 11: 383-289.

- Warholm O, et al: The effects of a standardized herbal remedy made from a subtype of Rosa Canina in patients with osteoarthritis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Current Therapeutic Research, 2003; 64 (1).

- Winther K, Kharazmi A: A powder prepared from seeds and shells of a subtype of rose-hip Rosa canina reduces pain in patients with osteoarthritis of the hand – a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study. P353, presented at the 9th World Congress OARSI, Chicago, 2004.

- Huang TH, et al: Harpagoside supresses lipopolysaccharide-induced iNOS and COX-2 expression through inhinbition of NF-kappa B activation. J Ethnopharmacol 2006; 104: 149-155.

- Kaszkin M, et al: Downregulation of INOS expression in rat mesangial cells by special extracts of Harpagophytum procumbens derives from harpagoside-dependent and independent effects. Phytomedicine 2004; 11: 585-595.

- Fiebich BL, et al: Molecular targets of the anti-inflammatory Harpagophytum procumbens /devil’s claw): inhibition of TNFα and CoX-2 gene expression by preventing activation of AP-1.

- Warnock M, et al: Effectiveness and safety of devil’s claw tablets in patients with general rheumatic disorders. Phytother Res 2007; 21: 1128-1233.

- Chantre P, et al: Efficacy and tolerance of Harpagophytum procumbens versus diacerhein in treatment of osteoarthritis. Phytomedicine 2000; 7: 177-183.

- Warnock M, et al: Effectiveness and safety of devil’s claw tablets in patients with general rheumatic disorders. Phytother Res 2007; 21: 1228-1233.

- Grant L, et al: A review of the biological and potential therapeutic actions of harpagophytum procumbens. Phytother Res 2007; 21: 128-150.

- Vlachojannis J, et al: Systematic review on the safety of Harpagophytum preparations for osteoarthritic and low back pain. Phytother Res 2008; 22: 149-152.