Studies of athletes with ambitions show that many do not pay the necessary attention to recovery after training. It is therefore not surprising that some performance curves do not point upwards as desired (and expected by the athlete) despite diligent training. And yet it would be relatively easy to achieve.

It is not uncommon – in the case of amateur athletes who discovered their sporting ambitions late in life, it is even the norm – to hear of weekly training workloads of between 60 and 80 km in running or over 300 km on the bike in five to six stages per week.

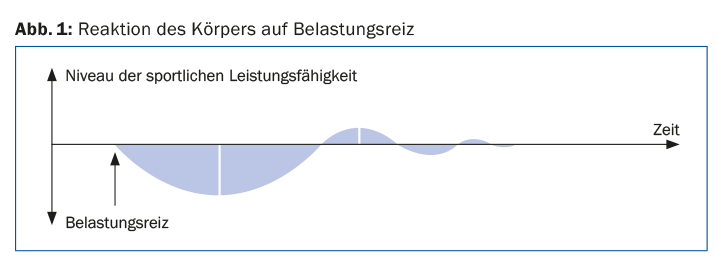

In sports, there is a lot of talk about training because people firmly believe that they can increase their performance “almost infinitely” with it. It is undisputed that training is an essential moment in the preparation of the athlete, however, it is often insufficiently understood that after any training, as well as after any other load, the performance of the body does not increase, but decreases for a certain time due to the work required. Figure 1 – a classic of German-language training theory – shows this clearly and at the same time explains how the resulting performance improvement can also be understood as a kind of “protective reaction” of the body against further training stimuli. Thus, before the desired increase in performance occurs, there is a decrease in performance, which is an expression of the peripheral and central fatigue that occurs after each performance and the consumption of “substance.” To create a movement, muscles are needed. These muscles must contract, which requires the use of the central nervous system as well as the muscle. The functioning of the nervous system and the musculature is only possible if various substances such as energy suppliers, hormones, vitamins, mineral salts and trace elements are integrated in complex chemical reactions to build up sugars and fats (and partly also proteins) for the purpose of energy production. All these substances, which are not present in unlimited quantities in the body, are lost during training and are therefore not immediately available for further stress. This explains what at first sight appears to be an astonishing drop in performance, and at the same time the pressing need for replacement and rest.

Duration of the power drop

What is the duration of the phase below the line (i.e. the phase below the value of the output power)? How to shorten them? These questions are not easy to answer because the measurement criteria are very diverse, depend on a wide variety of factors and are individual. A pulse that has returned to its initial value or a normalized blood glucose level does not necessarily mean a completely recovered state, since the organism as a biologically (very) complex system is composed of countless sub-functions that cannot be characterized with one or two measured values. In addition, there are large individual variations, not every athlete reacts in the same way. And the type of stress, its duration and repetitions (including the time intervals between stresses) also play an essential role.

Recovery measures

It seems natural to help the body back to baseline. This is the purpose of the recovery-promoting measures, which are dialectically closely linked to the stress itself, even if this is often forgotten, again in popular sports more than in competitive sports.

Recovery can involve a wide variety of measures, and the most common methods, which have been scientifically validated to a certain extent, will be presented in the following. Active measures can be: Running out, stretching, etc. Passive measures include:

- Relaxation measures: Sleep, psychoregulation (e.g., autogenic training, yoga), etc.

- Nutrition in the broadest sense of the word, i.e. replacement of the lost substrates such as fluids, electrolytes, carbohydrates and others

- Physical methods such as massages, baths, sauna, etc.

Example from professional sports

So you are spoiled for choice. It is essential not to neglect recovery and to include it as an integral part of the training program. The following example shows a recovery strategy as it is carried out in professional sports (soccer) after a match: Immediately after the final whistle, people start to compensate for the loss of fluids (approx. 2-3% of body weight; this must therefore be known) as completely as possible with drinks (with high Na concentrations). The drinks – solid food is usually not desired after an effort – should also contain carbohydrates and proteins in significant doses to promote glycogen resynthesis, which takes two to three days. During this favorable “window” replenishment takes place most rapidly. Dairy drinks are often offered to boost muscle protein synthesis, as well as juices (peach, berry or tomato) with high antioxidant activity. This is followed by a ten to twenty minute full body bath in cold water (12-15°C). Within one hour after the end of the game, a meal of high glycemic index carbohydrates and proteins is consumed. Later, compression stockings are put on to prevent venous congestion, then you go to sleep.

Connoisseurs of the subject (and also of the football scene) will be surprised that running out as an active recovery measure, as is so often observed, has not found a place in this protocol despite its scientifically proven effect. The reason: running out is particularly effective during stress with strong lactate accumulation, which is not necessarily the case in football. In addition, one has to go through the logistical and practical problems of such a regeneration process.

out into account: There is little time available to make the most of the favorable metabolic windows in nutrition.

Scientific data situation is good, mediation poor

Many of these recovery processes are quite well studied and documented in the scientific literature. Sleep can be cited as a prime example. This natural process has also been thoroughly studied in sports and especially as a regenerative measure, from the release of growth hormone (central to recovery) to effects of sleep on the coordinative-technical components of athletic performance such as mood and cognitive parameters (visual vigilance, complex reactivity, etc.) to the very interesting connections with nutrition, which is so important.

The same can be said of cold water immersion, whole body cryostimulation, or even electrostimulation – scientific data is available on these as well. Not to forget psychological measures for stress management and regeneration.

Unfortunately, this knowledge is poorly taught and therefore little known and consequently little systematically applied, except by top teams and athletes at top competitions. Another reason comes into play: a regeneration program, even if exactly as important as its counterpart, the training, can be complex and expensive. If the financial aspect is an obstacle, which is conceivable in the case of the young amateur athlete, it should not be forgotten that a bath in the bathtub with special bath additives is an absolutely useful and also simple method; there are even voices that attribute a much higher regenerative value to a bath in warm water than, for example, to massage. Even with this last measure, some (financial) relief can certainly be created by self-massage, a method that is not difficult to learn. Also, the correct diet does not require too much effort.

But we don’t have time!

Another excuse for neglecting recovery-enhancing measures is almost everyone’s chronic lack of time. However, everyone should be aware that if the “time” factor is not respected, all the measures taken to help the body recover for the next performance will prove useless. If a person is burdened by his occupation outside sport, by an extended training program, by family or other stressful situations, he will not succeed in renewing his strength from day to day even with intensive regeneration.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(3): 3-4