Therapy with anti-PD-1, anti-PDL-1 and anti-CTLA-4 antibodies can also achieve long-term remissions in patients with previously incurable tumor diseases. Whether a carcinoma patient will respond to treatment with checkpoint inhibitors can be assessed by certain predictive factors. Since there is a strong activation of the immune system in the course of immunotherapy, autoimmune side effects may occur. Interdisciplinary collaboration between oncologists and primary care physicians is needed to provide the best possible care for carcinoma patients.

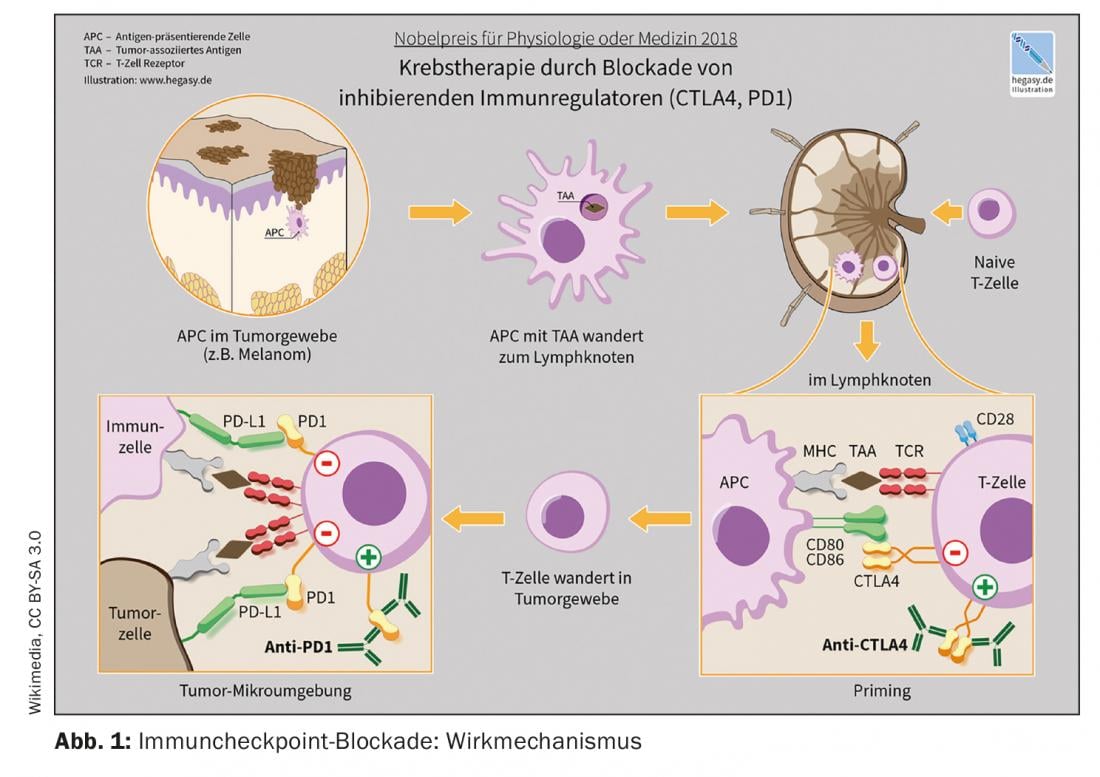

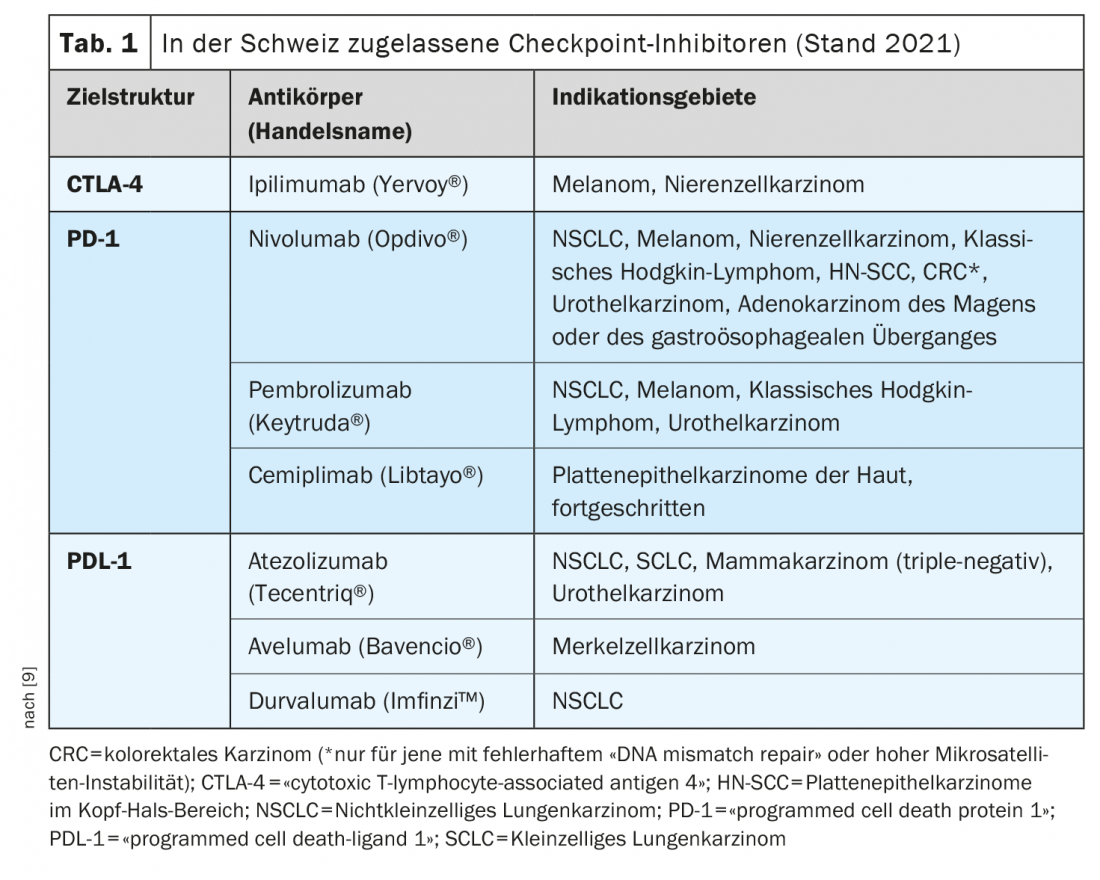

The market approval of the so-called checkpoint inhibitors is one of the most groundbreaking developments in immuno-oncology during the past years. The checkpoint inhibitors activate T cells in the fight against tumor cells. Several monoclonal antibodies targeting the immune checkpoints PD-1 (programmed death-1), PDL-1 (PD ligand 1), and CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4) are now available [1]. These treatment options are considered the new standard of care in an increasing number of tumor entities, either alone or in combination with chemotherapy, explains Raphaël Delaloye, MD, Tumor Center, University Hospital Basel [2]. Checkpoint inhibition is among the most commonly used strategies from the field of immunotherapy. Their efficacy is based on activating tumor defense by interrupting inhibitory interactions between antigen-presenting cells and T lymphocytes at the so-called checkpoints. “Immune checkpoint inhibitors can restore a balance between tumor cell and immune response,” the speaker elaborates [2]. With Ipilumumab (Yervoy®), the first anti-CTLA-4 antibody was approved in 2011, followed by the anti-PD-1 antibodies Nivolumab (Opdivo®) and Pembrolizumab (Keytruda®) in 2015. The combination of ipilimumab/nivolumab received Swissmedic approval in 2016 for melanoma treatment [2,3]. An example of the combined use of immune checkpoint inhibition and chemotherapy is the combination of pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1-Ak) plus carboplatin and paclitaxel or Nab-paclitaxel approved in Switzerland for first-line treatment of adults with metastatic squamous non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Is it possible to predict the response to therapy?

There are two major factors that explain why not all patients show the same response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. On the one hand, the relevance of the blocked mechanisms for tumor tolerance is decisive. Determination of PDL-1 expression in tumor samples has been shown to be a biomarker predictive of response to PD-1/PDL-1 inhibitors [4]. The speaker illustrated this with the following example: in the CheckMate 057 study, an association between the expression of PDL-1 with the clinical response to nivolumab in NSCLC as second-line therapy was shown [2,5]. Patients who had strong expression of PDL-1 were more likely to respond to anti-PDL-1 treatment, however, even those with less than 1% of PDL-1 showed a better response compared with chemotherapy (docetaxel) [2,5]. The second important factor for therapy response is the “microenvironment” of the tumor. The surrounding microenvironment of tumor cells plays an important role [2]. Depending on the presence of active immune cells in the tumor, it is referred to as inflamed (“hot”) or non-inflamed (“cold”) [6]. Inflammatory gene signatures are associated with better response to immunotherapies.

Management of side effects: What to watch out for?

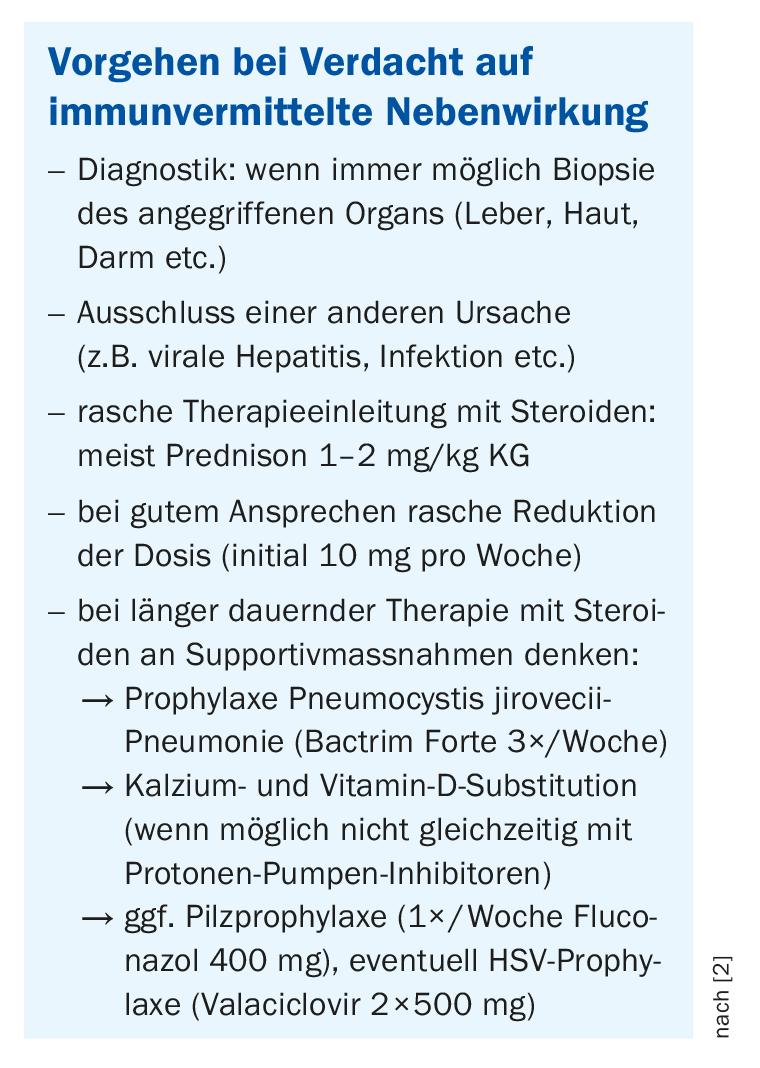

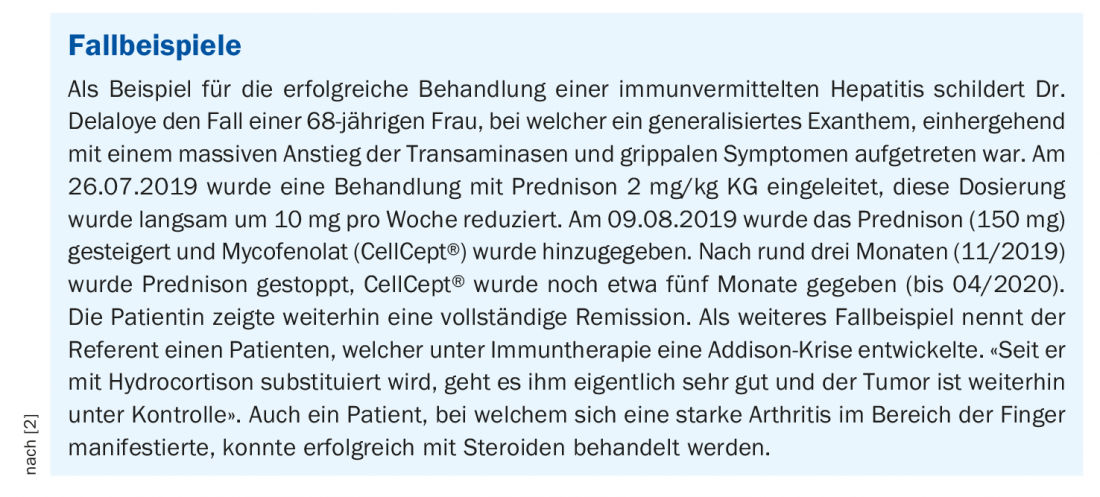

Immune checkpoint inhibitors can be used alone, combined with another immunotherapy (e.g., in melanoma), or in combination with chemotherapy (e.g., in NSCLC). The dose interval of checkpoint inhibition administered as an intravenous infusion is usually two or three weeks. “In general, this infusion does not require premedication, unlike chemotherapy,” Dr. Delaloye clarifies [2]. There is usually no acute toxicity such as nausea or allergic reaction, side effects usually occur with immunotherapy after a certain delay. The therapy-related strong activation of the immune system is accompanied by the danger that the immune cells also destroy the body’s own healthy tissue, whereby in principle every organ can be attacked. In some cases, these side effects can be life-threatening. Early detection is critical, and primary care physicians play a very important role, emphasizes Dr. Delaloye [2]. The most common side effects occur 6-8 weeks after the start of immunotherapy. Therefore, patients on immunotherapy should always be thought of as having an immune-mediated side effect when new symptoms occur. The most common are exanthema, diarrhea, colitis or gastritis. Less commonly, thyroid disease, renal insufficiency, hepatitis, or pneumonitis may occur. The lecturer recommends contacting the treating oncological specialists in case of corresponding suspicion and uses case studies to show how successful management of immune-mediated side effects can look (box) [2].

Cancer immunotherapy quo vadis – it remains exciting

Along with checkpoint inhibitors, T-cell therapies are among the most promising innovations in the field of immuno-oncology. Patients with advanced tumor diseases in particular can benefit from this. TCR (T cell receptor) gene therapy involves transplanting a mutation-specific T cell receptor into fresh T cells derived from patient blood. The T cells genetically modified in this way are not functionally restricted and can then, back in the body of the diseased person, fight the cancer [8]. CAR (chimeric antigen receptor) T-cell therapy is based on genetically engineered T cells with synthetic antigen-specific receptors. Tisagenlecleucel is an agent from the CAR-T cell group, which was approved in 2018 [7].

In addition, another major immuno-oncology topic is cancer vaccine research [7]. These are based on a similar principle to the checkpoint inhibitors, but should carry a lower risk of toxic side effects. For patients whose tumors lack neoantigens, scientists can draw on a large selection of largely tumor-specific germline antigen epitopes for vaccine development [7]. Moreover, research is focused on the further development of new technological platforms that generate highly complex biomarker profiles based on microscopic, genetic, molecular, and experimental analyses to better predict the success of therapeutic interventions [7].

Congress: Forum for Continuing Medical Education

Literature:

- Kähler KC, et al: for the Cutaneous Side Effects Committee of the Working Group on Dermatologic Oncology: JDDG 2020; 18(6): 582-609.

- Delaloye R: Immunotherapy and targeted therapies in oncology. Raphaël Delaloye, MD, Forum for Continuing Medical Education Jan. 27, 2022

- Drug Information, www.swissmedicinfo.ch (last accessed Mar. 30, 2022).

- Prelaj A, et al: Eur J Cancer 2019; 106: 144-159.

- Horn L, et al: J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: JCO2017743062-33.

- Hegde PS, Karanikas V, Evers S: Clin Cancer Res 2016; 22(8): 1865-1874.

- German Consortium forTranslational Cancer Research, https://dktk.dkfz.de (last accessed Mar. 30, 2022).

- Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine, www.mdc-berlin.de/de/news (last accessed Mar. 30, 2022).

- Riggenbach E, et al: Swiss Med Forum 2021; 21(0506): 78-82.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(4): 38-39