Psoriasis sufferers have an increased risk of affective disorders. Accordingly, they should be asked about depression, anxiety, and problematic coping with illness such as social avoidance behavior and alcohol abuse. Training courses on daily living, nutrition and skin care exist and have proven useful. Physicians and patients should be aware of the increased risk for cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus. Lifestyle and diet (low-calorie, preferably Mediterranean) should be adjusted. The importance of obesity and smoking as proven risk factors and also their sometimes negative effects on therapy should be explained to the patient. Appropriate lifestyle changes should be supported. Psoriatic patients should be asked about symptoms of gluten sensitivity and tested for gluten antibodies if positive. Complex and expensive therapies could be saved by a gluten-free diet.

The treatment of psoriasis is primarily guided by immunomodulatory topical and systemic therapeutics as well as phototherapy. Many people are not aware that psoriasis, as a multifactorial disease, can also be favorably influenced by lifestyle measures. Since not all sufferers respond the same way to the various measures, there is no specific psoriasis lifestyle or diet. Those affected must do much more to identify the influencing factors that are relevant to them and become aware of the possibilities for exerting their own influence. The factors of stress, psychological comorbidities, diet, obesity, and smoking are discussed below.

Psoriasis – current knowledge and treatment standards

Psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory skin disease with a prevalence of approximately 2-3% in the general population. The etiology is not fully understood, but a multifactorial genesis is assumed with genetic, environmental, and behavioral factors, which most likely also explains the variability in prevalences between different countries (USA 0.9%, Norway 8.5%) [1]. The course can fluctuate widely and be associated with a reduction in quality of life similar to that of cardiovascular disease and certain cancers [2].

In recent years, new potent but also cost-intensive immunosuppressants, the biologics, have become increasingly important in psoriasis treatment. This is associated with increasing treatment costs (25,000-35,000 CHF per year), especially considering the chronicity of this disease. It is therefore all the more important to pay attention to unrecognized etiologic factors that may favorably influence therapy or prevent exacerbations.

In order to therapeutically address the multifactorial genesis, a multimodal approach should be adopted. Genetic predisposition per se cannot be changed, of course – but in recent years it has become increasingly clear that lifestyle and diet affect gene activation via epigenetic mechanisms and influence inflammatory processes [3]. At the same time, the increased risk of comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus can be reduced as a result.

Psyche and stress

Skin diseases are associated with considerably increased comorbidity for mental illness.

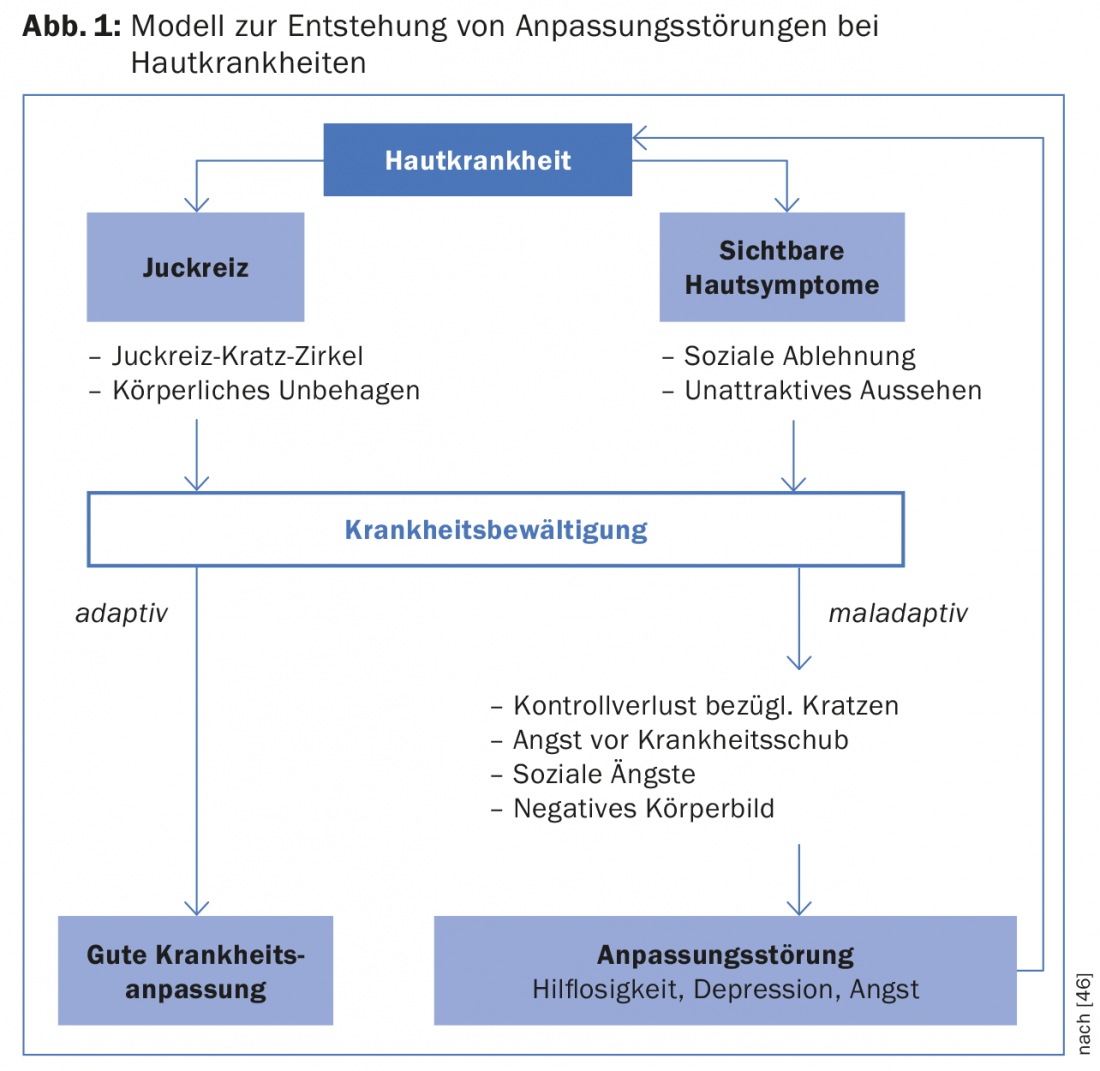

The extent of these associations was again highlighted in a European multicenter cross-sectional study published in 2014. In thirteen states, 3635 persons with skin disease and 1359 controls were surveyed regarding depression, anxiety disorder, and suicidal ideation. Psoriasis represented the largest group (17.4%). Overall, the disturbance patterns mentioned occurred almost twice as frequently in the skin patients (29%) as in the control group (16%). Depression occurred more than twice as often, and anxiety disorders or suicidal thoughts about one and a half times as often as in the control group. The psoriasis subgroup in particular showed high values for these three disorders (13.8%, 22.7%, and 17.3%, respectively) [4]. The psychological condition can be caused by the disease symptoms themselves, the experience of stigmatization, social fears or a negative body image (Fig. 1) . On the other hand, psychological stress, i.e. emotional stress (referred to in the following as “stress”), can also trigger psoriasis attacks or worsen the course of the disease.

Stress: Generally, emotional stress is observed as a trigger of various dermatological diseases such as atopic dermatitis, acne vulgaris and chronic urticaria. Studies also show a consistent association between stress and clinical expression in psoriasis [5]. In fact, a large proportion of psoriasis sufferers identify stress as the main cause of exacerbations, ahead of infections, trauma, medications, and diet [6]. However, disease severity and treatment outcome can also be negatively affected by stress [7,8]. Conversely, psychological interventions are often associated with clinical improvement [9,10]. However, in accordance with the multifactorial genesis, this does not apply to all psoriasis sufferers. A distinction is made here between so-called “stress responders” and “stress non-responders” [11].

Between 39% and 61% of psoriasis sufferers are “stress responders” [12]. The studies classified stress into three categories: major stressful life events, psychological or personality difficulties, and lack of social support.

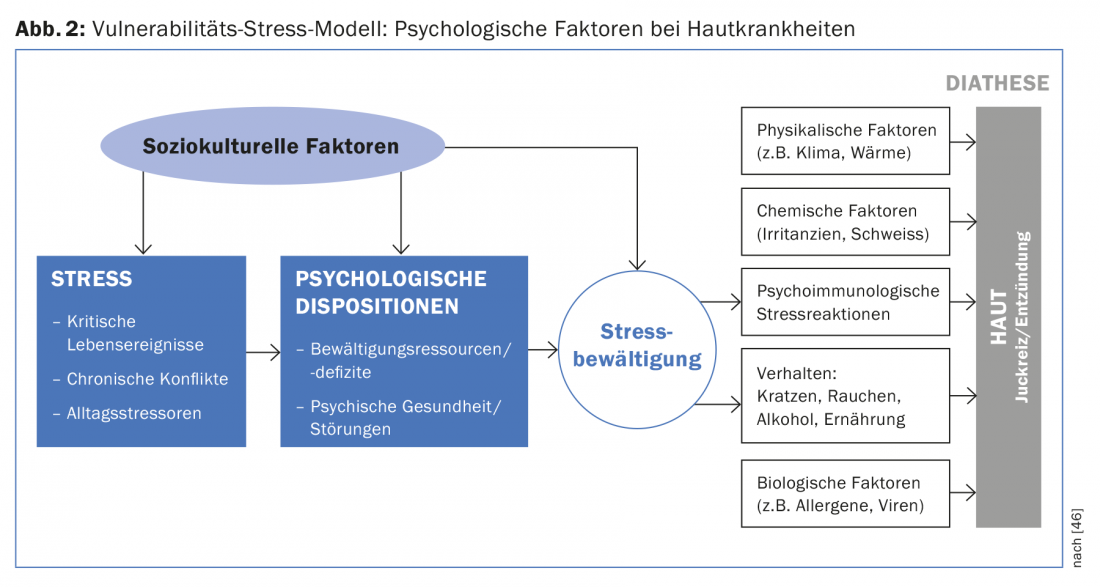

Stress is always a subjective experience and arises when a demand (from the environment or from oneself) or its assessment exceeds the available resources (e.g. social support, personality style, solution strategies). (Fig. 2). In a recent cross-sectional study, “stress responders” were found to have significantly elevated scores for depression and personality traits such as anxiety, distrust, and lack of assertiveness [13]. Thus, it appears to be a more psychologically vulnerable population. Few prospective studies on stress and psoriasis exist [7,14,15] and the exact relationships and mechanisms are not fully understood.

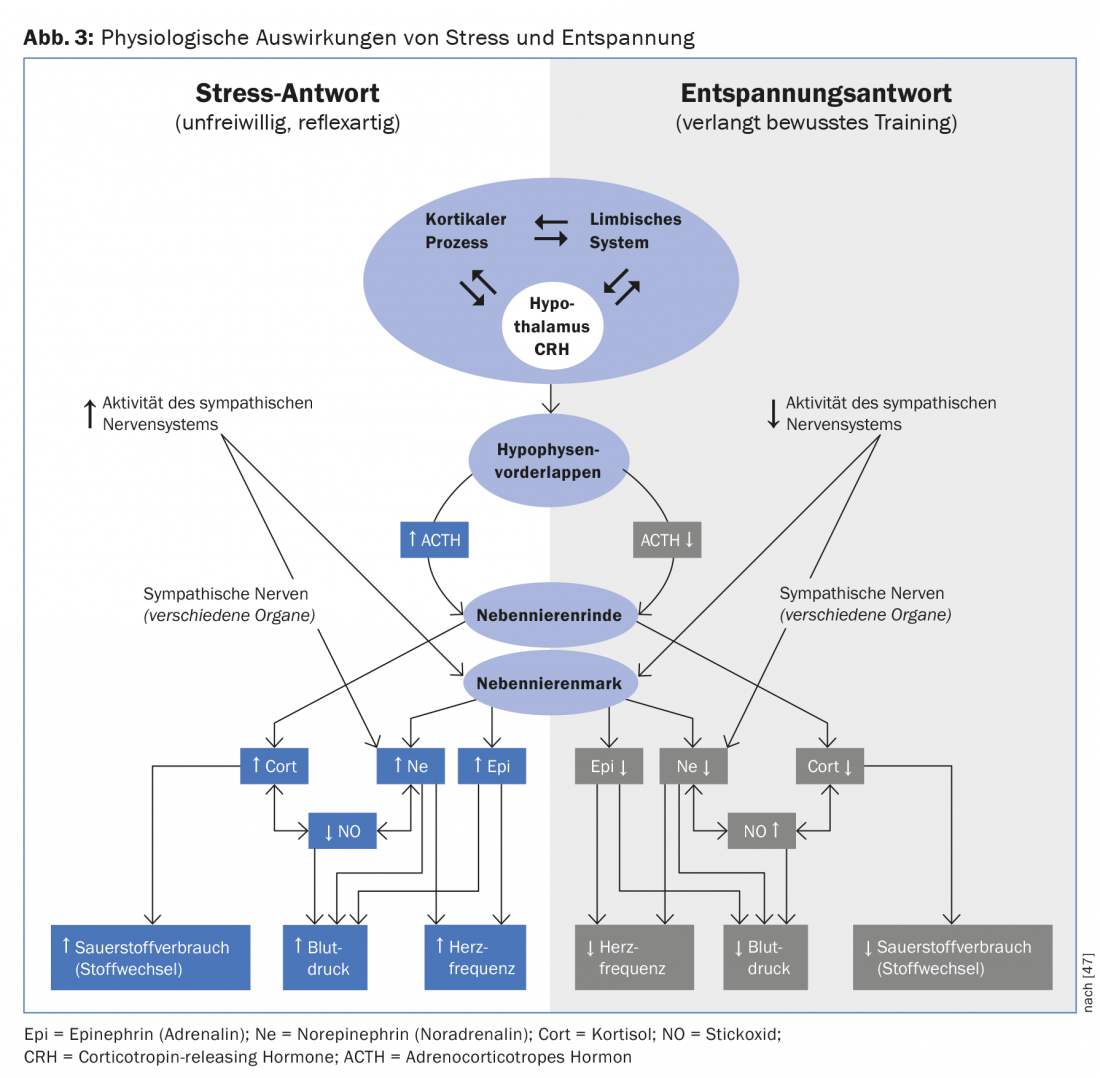

However, this subgroup exhibits different stress biomarkers, as evidenced by attenuated cortisol release after acute stress [16]. Several experimental studies have demonstrated an attenuated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response and an enhanced sympathetic catecholaminergic response to stress in psoriasis sufferers, corresponding to lower cortisol and higher catecholamine release during stress [16–19]. These changes attenuate the endogenous anti-inflammatory effect, which increases the release of proinflammatory cytokines, activates skin mast cells, and impairs skin barrier function [19]. Thus, a similar mechanism as in the flare-up of psoriasis after steroid withdrawal.

Therapy: In view of the high comorbidity of affective disorders, psychotherapeutic, educational and stress reduction measures are recommended. However, the evidence base for specific interventions is heterogeneous and larger randomized controlled trials are lacking. However, it is important to remember that psychological interventions are more difficult to standardize than pharmacological interventions because they are dependent on the user and on participant preference and compliance. Among the best-studied methods are cognitive behavioral therapy, Jakobson progressive muscle relaxation, and mindfulness meditation [12]. Central and independent of the method is the induction of a state of relaxation (“relaxation response”) to counteract the stress state. Antagonistic physiological-hormonal mechanisms have been described for this (Fig. 3). This mechanism can also be supported by endurance sports and sufficient sleep.

The gold standard is considered to be cognitive behavioral therapy in a multidisciplinary group setting over six weeks, which according to studies is associated with improvement in physical, psychological, and quality-of-life parameters [9]. This approach is all the more important because illness experience has been identified as the strongest predictor of stress and disability [20].

Influences of nutritional factors

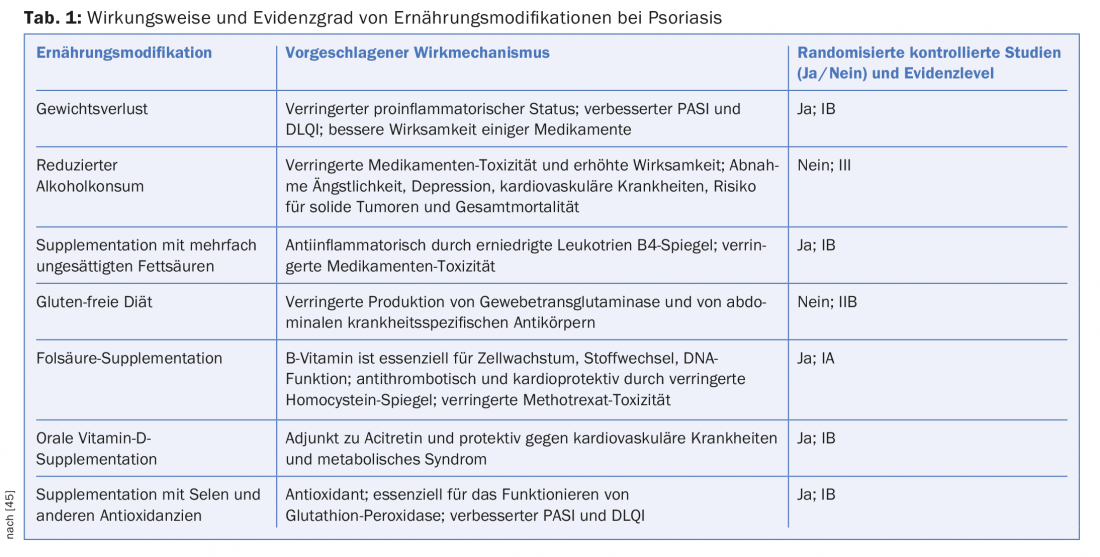

In recent years, it has become increasingly clear that numerous dietary components exert an inflammation-modulating effect on chronic low-grade inflammation [21]. Especially for the Mediterranean diet with its high proportion of fruits, vegetables, nuts and fish, this has been epidemiologically proven [22]. This effect is attributed to the numerous phytonutrients, fibers and omega-3 fatty acids. In contrast, refined carbohydrates and various fats tend to be pro-inflammatory [23]. Although these are low-threshold effects, over the years the effect accumulates not insignificantly. If the diet is strongly altered in favor of a low-carbohydrate so-called “ketogenic diet,” more potent effects on inflammation are possible, as has been shown for neurological diseases, cancer, and acne [24]. Likewise, this effect is supported by the intake of marine omega-3 fatty acids (fatty sea fish) [25]. However, there is little conclusive evidence for specific diets in psoriasis. This is probably due to individual variability and research methodological difficulties. Thus, individual dietary components such as gluten, fatty acids, vitamin D, and antioxidant supplements have been increasingly studied. It has been shown that a diet rich in fresh fruits and vegetables is associated with a lower risk of psoriasis [26]. Among supplements, omega-3 fatty acids were found to be most likely to benefit, although the data are inconclusive. An overview of the study situation is provided in Table 1.

Fatty acids: Polyunsaturated fatty acids, which include omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids, are significantly involved in inflammatory processes in addition to their hormonal and immunological functions. Elevated levels of arachidonic acid, an omega-6 fatty acid, are found in the skin of psoriatic plaques. Arachidonic acid is converted by the enzyme phospholipase A2 to leukotriene B4, a potent proinflammatory mediator. The same enzyme converts EPA, an omega-3 fatty acid, into leukotriene B5 and prostaglandin-E3, which have lower inflammatory activity. In this process, omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids compete for the same enzyme. Thus, the presence of the fatty acid substrate is critical for the more or less inflammatory metabolites. Increased levels of omega-3 fatty acids are thought to have an anti-inflammatory effect and improve psoriasis symptoms [27]. However, studies on omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in psoriasis have not shown any conclusive effects. This is not surprising since serum baseline values were not measured and different supplement doses and bioavailabilities existed. Accordingly, the strongest effects were shown by lipid infusion treatments.

Gluten: Psoriasis sufferers have a higher prevalence of other autoimmune diseases such as celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis. Studies suggest common genetic and inflammatory processes [28]. In a large American cohort study [29], psoriasis sufferers (n=25 341) had a 2.2-fold increased risk for the presence of celiac disease and a 2.4-fold increased risk for gluten sensitivity (pos. anti-gliadin antibodies, no enteropathy). Accordingly, a gluten-free diet was shown to significantly reduce psoriasis severity in individual case reports [30,31] and two clinical trials of AGA-positive patients [32,33]. This suggests an association between gluten sensitivity and psoriasis, especially since evidence of increased intestinal permeability has been found in psoriasis [34].

Weight loss: visceral obesity is associated with a proinflammatory state via secretion of cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 from adipocytes. In several studies, obesity was associated with increased psoriasis incidence and severity as well as attenuated therapeutic effect of certain drugs [35]. Furthermore, the cytokines IL-17 and IL-23, which are relevant to psoriasis, were elevated in obese women but not in lean women [36]. In a large English cohort study of 75 395 psoriasis patients, obesity was recognized as a risk factor for developing psoriatic arthritis [37]. Several prospective controlled studies of weight reduction using calorie-restricted diets in obesity have demonstrated an effect on psoriasis severity and arthritis that is additive to dermatologic treatment [35]. Interestingly, a reduction in circulating inflammatory cytokines was observed in obese individuals as a result of the calorie-restricted diet [38]. Also very illustrative are the effects of bariatric surgery, which produced considerable improvement in psoriatic activity in several case studies [39,40].

Psoriasis sufferers have an increased cardiovascular risk and also an increased risk of diabetes [41]. The cause is thought to be reduced insulin sensitivity due to systemic inflammation. Similarly, it is itself an independent cardiovascular risk factor [42]. It is therefore all the more important that psoriasis sufferers are aware of this risk and take care of their lifestyle accordingly.

Smoking and alcohol

An analysis of several large cohort studies (Nurses Health Study, Health Professionals’ Follow-up Study) confirmed smoking as an independent risk factor with gradually increased incidence risk depending on the number of pack-years and duration of cigarette use. The relative incidence risk for 5-24 cigarettes daily was even twice as high (RR 2.04) [43]. A prospective study in patients with palmoplantar pustulosis even demonstrated clinical improvement after smoking cessation compared with smoking persistence [44].

Overconsumption of alcohol is also common in psoriasis patients and correlates with disease severity and treatment response [45]. However, a causal relationship could not be confirmed. This behavior is just as conceivable as a reaction to the burden of disease.

Literature:

- Parisi R, et al: Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2013; 133(2): 377-385.

- Rapp SR, et al: Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 1999; 41(3): 401-407.

- Alegría-Torres JA, Baccarelli A, Bollati V: Epigenetics and lifestyle. Epigenomics 2011; 3(3): 267-277.

- Dalgard F, et al: The psychological burden of skin diseases: a cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2015; 135(4): 984-991.

- Heller M, Lee ES, Koo JY: Stress as an influencing factor in psoriasis. Skin Therapy Lett 2011; 16(5): 1-4.

- Rigopoulos D, et al: Characteristics of psoriasis in Greece: an epidemiological study of a population in a sunny Mediterranean climate. European Journal of Dermatology 2010; 20(2): 189-195.

- Verhoeven EWM, et al: Individual differences in the effect of daily stressors on psoriasis: a prospective study. British Journal of Dermatology 2009; 161(2): 295-299.

- Fortune DG, et al: Psychological distress impairs clearance of psoriasis in patients treated with photochemotherapy. Archives of Dermatology 2003; 139(6): 752-756.

- Fortune DG, et al: A cognitive-behavioural symptom management programme as an adjunct in psoriasis therapy. British Journal of Dermatology 2002; 146(3): 458-465.

- Fordham B, Griffiths CEM, Bundy C: A pilot study examining mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in psoriasis. Psychology, Health & Medicine 2015; 20(1): 121-127.

- Koo J: Psychodermatology: a practical manual for clinicians. Current problems in dermatology 1995; 7(6): 204-232.

- Fordham B, Griffiths CEM, Bundy C: Can stress reduction interventions improve psoriasis? A review. Psychology, health & medicine 2013; 18(5): 501-514.

- Remröd C, Sjöström K, Svensson Å: Subjective stress reactivity in psoriasis – a cross sectional study of associated psychological traits. BMC dermatology 2015; 15(1): 6.

- Gaston L, et al: Psoriasis and stress: a prospective study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 1987; 17(1): 82-86.

- Berg M, et al: Psoriasis and stress: a prospective study. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2008; 22(6): 670-674.

- Richards HL, et al: Response of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis to psychological stress in patients with psoriasis. British Journal of Dermatology 2005; 153(6): 1114-1120.

- Arnetz BB, et al: Stress and psoriasis: psychoendocrine and metabolic reactions in psoriatic patients during standardized stressor exposure. Psychosomatic medicine 1985; 47(6): 528-541.

- Buske-Kirschbaum A, et al.: Endocrine stress responses in TH1-mediated chronic inflammatory skin disease (psoriasis vulgaris) – do they parallel stress-induced endocrine changes in TH2-mediated inflammatory dermatoses (atopic dermatitis)? Psychoneuroendocrinology 2006; 31(4): 439-446.

- Evers AWM, et al: How stress gets under the skin: cortisol and stress reactivity in psoriasis. British Journal of Dermatology 2010; 163(5): 986-991.

- Fortune DG, et al: Psychological stress, distress and disability in patients with psoriasis: consensus and variation in the contribution of illness perceptions, coping and alexithymia. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 2002; 41(2): 157-174.

- Calder PC, et al: Dietary factors and low-grade inflammation in relation to overweight and obesity. British Journal of Nutrition 2011; 106(S3): S1-S78.

- Casas R, Sacanella E, Estruch R: The immune protective effect of the Mediterranean diet against chronic low-grade inflammatory diseases. Endocrine, metabolic & immune disorders drug targets 2014; 14(4): 245.

- Forsythe CE, et al: Comparison of low fat and low carbohydrate diets on circulating fatty acid composition and markers of inflammation. Lipids 2008; 43(1): 65-77.

- Paoli A, et al: Beyond weight loss: a review of the therapeutic uses of very-low-carbohydrate (ketogenic) diets. European journal of clinical nutrition 2013; 67(8): 789-796.

- Paoli A, et al: Effects of n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (ω-3) Supplementation on Some Cardiovascular Risk Factors with a Ketogenic Mediterranean Diet. Marine drugs 2015; 13(2): 996-1009.

- Naldi L, et al: Dietary factors and the risk of psoriasis. Results of an Italian case-control study. Br J Dermatol 1996; 134: 101-106.

- Ricketts JR, Rothe MJ, Grant-Kels JM: Nutrition and psoriasis. Clinics in dermatology 2010; 28(6): 615-626.

- Bhatia BK, et al: Diet and psoriasis, part II: celiac disease and role of a gluten-free diet. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2014; 71(2): 350-358.

- Wu JJ, et al: The association of psoriasis with autoimmune diseases. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2012; 67(5): 924-930.

- Addolorato G, et al: Rapid regression of psoriasis in a coeliac patient after gluten-free diet. Digestion 2003; 68(1): 9-12.

- Frikha F, Snoussi M, Bahloul Z: Osteomalacia associated with cutaneous psoriasis as the presenting feature of coeliac disease: A case report. Pan African Medical Journal 2012; 11: 58.

- Michaëlsson G, et al: Psoriasis patients with antibodies to gliadin can be improved by a gluten-free diet. British Journal of Dermatology 2000; 142(1): 44-51.

- Michaëlsson G, et al: Gluten-free diet in psoriasis patients with antibodies to gliadin results in decreased expression of tissue transglutaminase and fewer Ki67+ cells in the dermis. Acta dermato-venereologica 2002; 83(6): 425-429.

- Humbert P, et al: Intestinal permeability in patients with psoriasis. Journal of dermatological science 1991; 2(4): 324-326.

- Debbaneh M, et al: Diet and psoriasis, part I: impact of weight loss interventions. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2014; 71(1): 133-140.

- Sumarac-Dumanovic M, et al: Increased activity of interleukin-23/interleukin-17 proinflammatory axis in obese women. International Journal of Obesity 2009; 33(1): 151-156.

- Love TJ, et al: Obesity and the risk of psoriatic arthritis: a population-based study. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 2012; 71(8): 1273-1277.

- Hermsdorff HHM, et al: Discriminated benefits of a Mediterranean dietary pattern within a hypocaloric diet program on plasma RBP4 concentrations and other inflammatory markers in obese subjects. Endocrine 2009; 36(3): 445-451.

- Hossler EW, Maroon MS, Mowad CM: Gastric bypass surgery improves psoriasis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2011; 65(1): 198-200.

- Farias MM, et al: Psoriasis following bariatric surgery: clinical evolution and impact on quality of life on 10 patients. Obesity surgery 2012; 22(6): 877-880.

- Gyldenløve M, et al: Patients with psoriasis are insulin resistant. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2015; 72(4): 599-605.

- Coumbe AG, Pritzker MR, Duprez DA: Cardiovascular risk and psoriasis: beyond the traditional risk factors. The American journal of medicine 2014; 127(1): 12-18.

- Li W, et al: Smoking and risk of incident psoriasis among women and men in the United States: a combined analysis. American journal of epidemiology 2012; 175(5): 402-413.

- Michaëlsson G, Gustafsson K, Hagforsen E: The psoriasis variant palmoplantar pustulosis can be improved after cessation of smoking. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2006; 54(4): 737-738.

- Murzaku EC, Bronsnick T, Rao BK: Diet in dermatology: Part II. Melanoma, chronic urticaria, and psoriasis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2014; 71(6): 1053.e1-e16.

- Stangier U: Skin diseases and body dysmorphic disorder. Göttingen, Hogrefe, 2002.

- Dusek JA, Benson H: Mind-body medicine: a model of the comparative clinical impact of the acute stress and relaxation responses. Minnesota medicine 2009; 92(5): 47-50.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2015; 25(6): 26-32