The pioneer program was initiated by the Meiringen Private Clinic and is scheduled to run for several years. “Insanely Human” is part of Curriculum 21, and the workshops are oriented toward process-oriented work, enabling students and teachers to achieve a high level of authenticity, mutual understanding, and transparency. Learning modules and techniques were derived and adapted from empirical research.

After establishing the public cinema film series “insanely human” in 2014 as a community-based awareness program for understanding mental disorders, the Meiringen Private Clinic has scheduled another prevention project for 2015. The school project “madly human” serves to destigmatize mental illness and to raise public awareness in schools in the region. The basic idea is that mental stress or illness can affect anyone – including children. In the school project “insanely human”, school children, their parents and teachers are given the opportunity to deal with mental health, its maintenance and possible mental illness.

Aims of the project

- Promote awareness, openness, communication and transparency in the classroom setting.

- Sensitization of parents and teachers regarding possible psychological problems in school children and destigmatization

- Promoting cooperation between different systems

- Primary and secondary prevention of mental disorders

- Consulting, networking and assistance in case of need for action

Why at school in particular?

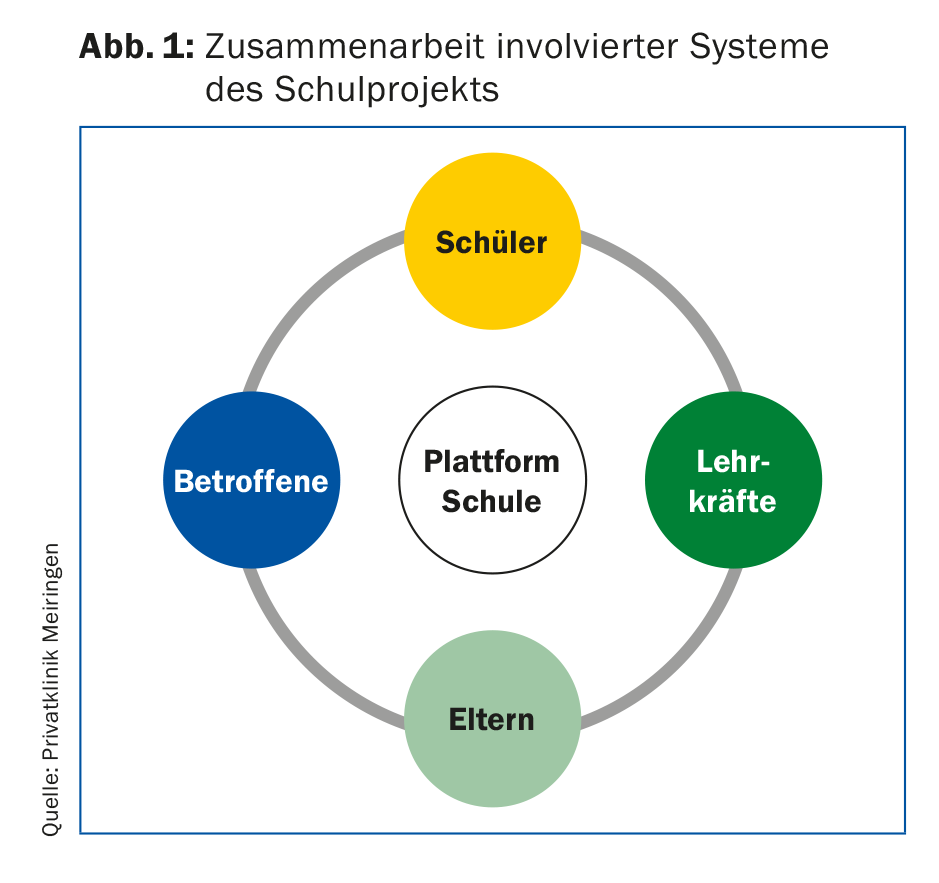

People with mental illness, parents, adolescents and children may be marginalized by others due to ignorance. With the school project “insanely human” we want to promote openness and tolerance and support affected students and teachers in solving interaction problems with other students. Mental health impairments can develop in childhood and adolescence, become entrenched throughout life, and continue to manifest in adulthood. Especially when it is not known how mental health problems manifest themselves, so they are not recognized and may not be treated at an early stage. The school building provides an ideal platform for involving many groups of people with little effort (Fig. 1).

Methodology

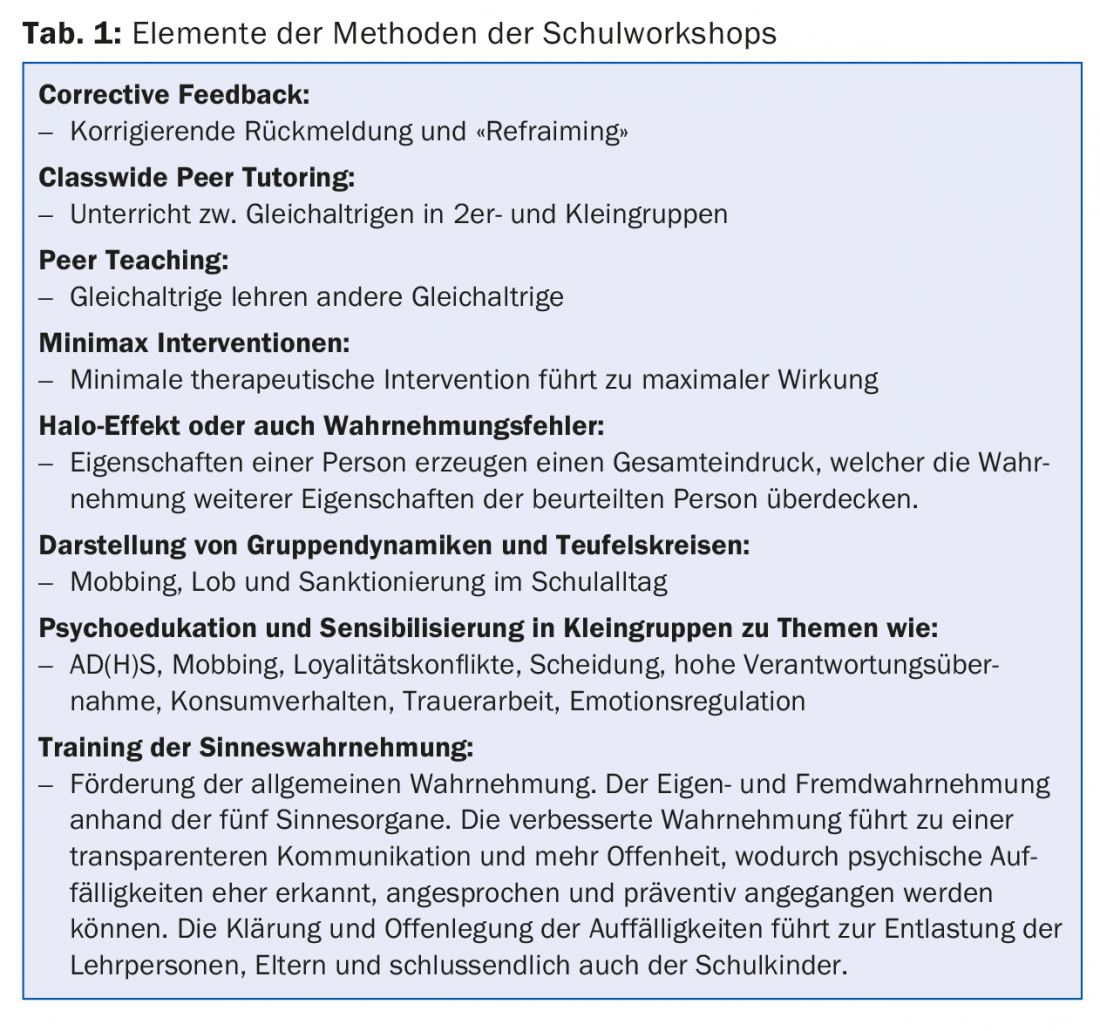

“Quality of life depends not least on how a person treats himself”. In line with Curriculum 21, the school project represents an important contribution to prevention work in schools. Curriculum 21 requires that schoolchildren learn to talk about themselves, to perceive themselves and others, to take co-responsibility for health and well-being, and to reflect on gender and roles. This is not primarily about educational work, but about teaching the appropriate tools. Workshops with students promote mindfulness, differentiated self-awareness, and improved perception of one’s own state of mind (Tab. 1).

Practical implementation

Together with the teachers, a half-day workshop of four lessons is held once a year for each of the nine school classes. Various topics of the human psyche are discussed. The students should be sensitized through different experiences and learn to be more attentive to themselves and their needs. The goal is a mindful approach to the feelings and sensations perceived in the workshops. This makes it possible to take feelings seriously in a different context, to communicate them and to ask for help if needed. For example, in the third grade workshop, students learn to distinguish pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral smells based on their sense of smell. They also learn what influence the sense of smell can have on memories and the emotional world. For example, the experience of grief regarding the loss of a pet (hamster) and the influence of smelling a similar odor (straw) during this time is discussed. This can be used to point out the importance of grief work and how to constructively cope with the various stages of grief. In the second grade, after mindfulness training with the sensory organ of the eye, school children are introduced to stereotypical thought patterns in a playful way, which can introduce the topic of racial discrimination in the classroom context if needed. In sixth grade, the inclusion of an anorexia patient (peer) illustrates and discusses stress in everyday school life, media pressure, slimming mania, bullying, and distorted perceptions.

Parents’ event

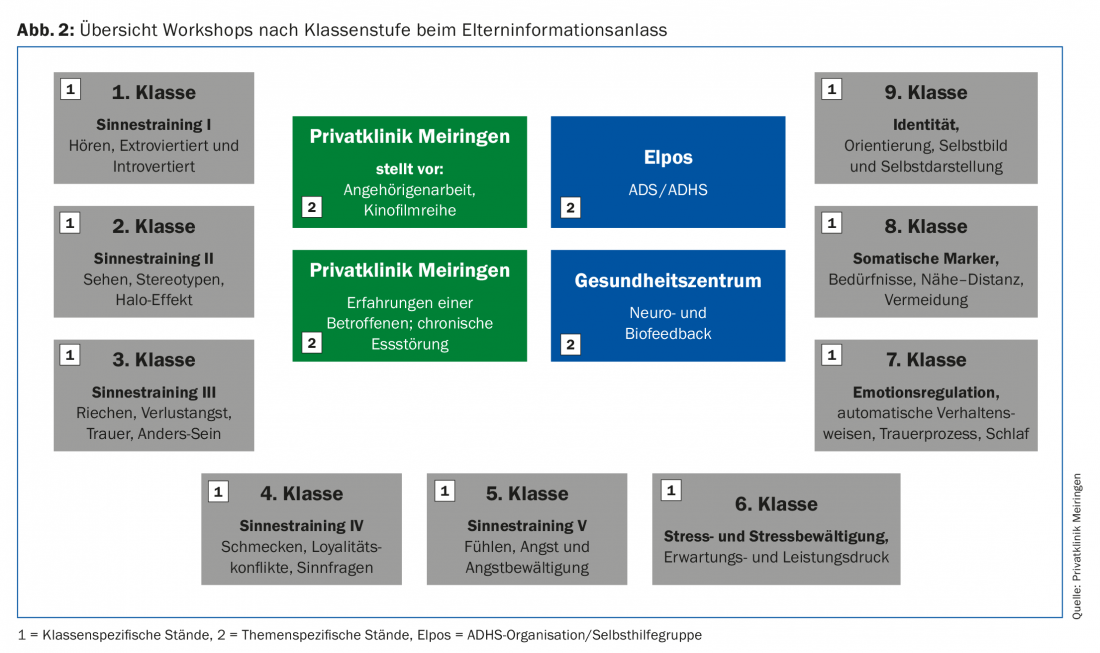

At the parents’ information evening, one week before the start of the project, parents are informed about the content of the workshops at information stands (Fig. 2) . The stands are staffed by specialists from the Meiringen Private Clinic as well as by external specialists. Parents should be brought into the experience and educated about the workshops so they know in advance what their children will experience the next week. The anorexia patient (peer) mentioned above also staffs a booth. This gives parents the opportunity to learn more about the clinical picture.

Resonance and relevance for primary and secondary prevention of mental disorders.

The response after the first pilot test in 2016 was very great. Principals provided feedback that several students contacted them after the project week to address personal, family, as well as school problem areas. One girl found the courage to show her self-injuries to the school administration and asked for help. Several parents reported their concern that their child might have an eating disorder and were more willing to accept help. Parents also reported back that their children would communicate with them more openly and transparently than before.

Feedback before the second run in 2017 showed that parents as well as teachers contacted us before the project week to announce current problem areas such as bullying, racial discrimination and possible conspicuousness. These could then be flexibly integrated into the corresponding workshops and conveyed and demonstrated to the students together with the teacher. A strikingly positive aspect of the project week was that in each class, when asked if the students could remember what they had done together last year, they were able to recall the core elements of the workshops.

Conclusion

- “Insanely Human” is a pilot project in selected communities, which has been carried out twice so far and is repeated annually. The response from teachers, parents and schoolchildren has been great.

- The focus is on direct student experience in the classroom setting, information transfer, and mental and physical health prevention.

- A second focus is the collaboration of teachers, parents, and support systems to identify and address student problems early.

Literature:

- Anhalt, K, Mc Neal, CB, Bahl, AB: The ADHD classroom kit: A whole-classroom approach for managing disruptive behavior. Psychology in the schools 1998; 35(1): 67-79.

- Dineen, JP, Clark, HB, Risley, TR: Peer tutoring among elementary students: Educational benefits to the tutor. J Appl Behav Anal 1977; 10(2): 231-238.

- Döpfner, M, Schürmann, S, Frölich, J: Therapy program for children with hyperkinetic and oppositional problem behavior THOP. 2002; Weinheim: Beltz PVU.

- DuPaul, et al: Peer tutoring for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Effects on classroom behavior and academic performance. J Appl Behav Anal 1998; 31(4): 579-592.

- DuPaul, GJ, Eckert, TL: The Effects of School-based interventions for students with attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis. School Psychology Review 1997; 26(1): 5-27.

- Greenwood, CR, Delquadri, J: (1995) Classwide peer tutoring and the prevention of school failure. Preventing School Failure 1995; 39(4): 21-25.

- Greenwoold, CR: Achievement, placement and services: Middle school benefits of classwide peer tutoring used at the elementary school. School Psychology Review 1993; 22(3): 497-516.

- Kalkowsky, P: Peer and Cross-Age Tutoring. School Improvement Research Series. Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory 2001; www.nwrel.org/scpd/sirs/9/c018.htm

- Rufer, M: Capture complex, act simple. Systemic psychotherapy as a practice of self-organization – a learning book. Göttingen 2012; Vandenhoexk & Ruprecht.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(9): 35-37

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2017; 15(5): 30-32.