Chronic pain is the most common health problem reported by patients with paraplegia. Due to the occurrence of different types of pain and pain mechanisms within the bio-psycho-social model of disease, pain management in this patient group is particularly challenging.

Chronic pain is the most common health problem reported by patients with paraplegia. Due to the occurrence of different types of pain and pain mechanisms within the bio-psycho-social model of disease, pain management in this patient group is particularly challenging. This can succeed in an interdisciplinary team, as recent data show. In the following, the occurrence, significance and pathophysiology of chronic pain in paraplegia as well as diagnostic and therapeutic approaches are discussed.

Occurrence and importance

Among the five most frequently reported health problems in patients with paraplegia in Switzerland, pain ranks first [1], ahead of problems with bladder function, personal hygiene, bowel emptying, and walking, respectively. A review highlights the comprehensive impact of pain on various somatic, psychological, and social levels [2]. For example, chronic pain can persist and worsen over time, negatively impact rehabilitation participation and outcomes, lead to functional disability with loss of mobility, reduce quality of life, disrupt sleep, interfere with participation in activities of daily living, and make it difficult to return to work. The presence of neuropathic pain in the early phase of three to six months after injury makes the persistence of this pain likely after three to five years.

Recent Swiss data report a high prevalence of 74% of chronic pain in patients with paraplegia, as well as risk factors such as female gender, older age, financial hardship, and also secondary health problems [3]. The high prevalence data are also consistent with internationally known data with a pain prevalence in paraplegics of 84% [4]. Among these, in addition to musculoskeletal pain, which shows a prevalence of 59%, neuropathic pain also occupies a high place (neuropathic pain at injury level 41%, below injury level 34%). Among musculoskeletal pain, back pain is the most common at 43-55% [5] and shoulder pain at 35% [6]. The high prevalence of spasticity in paraplegia of 71% [7] is significant because of existing associations between spasticity and pain [8].

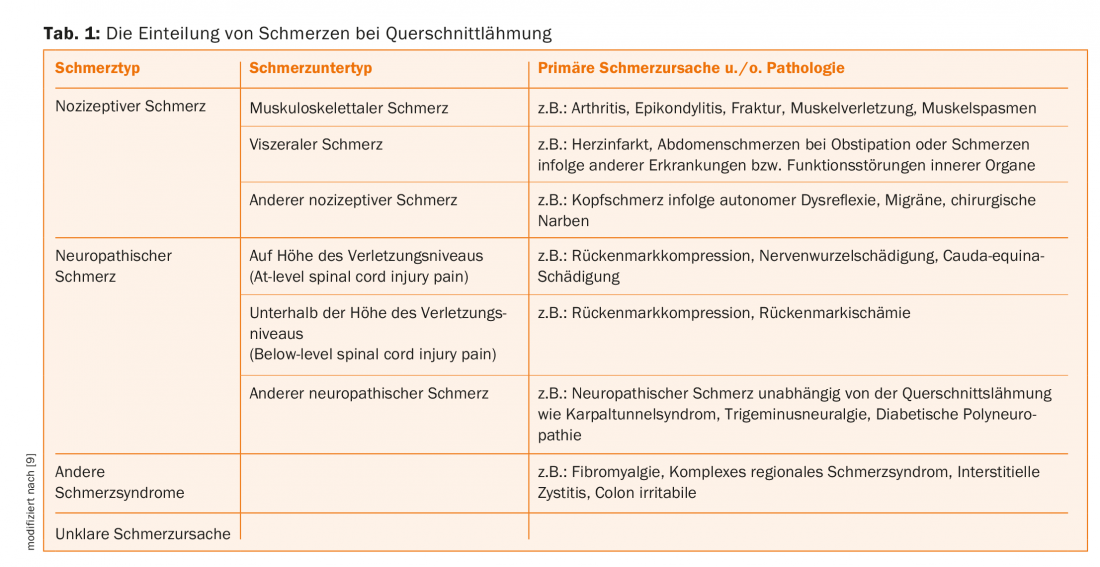

Classification of pain in paraplegia

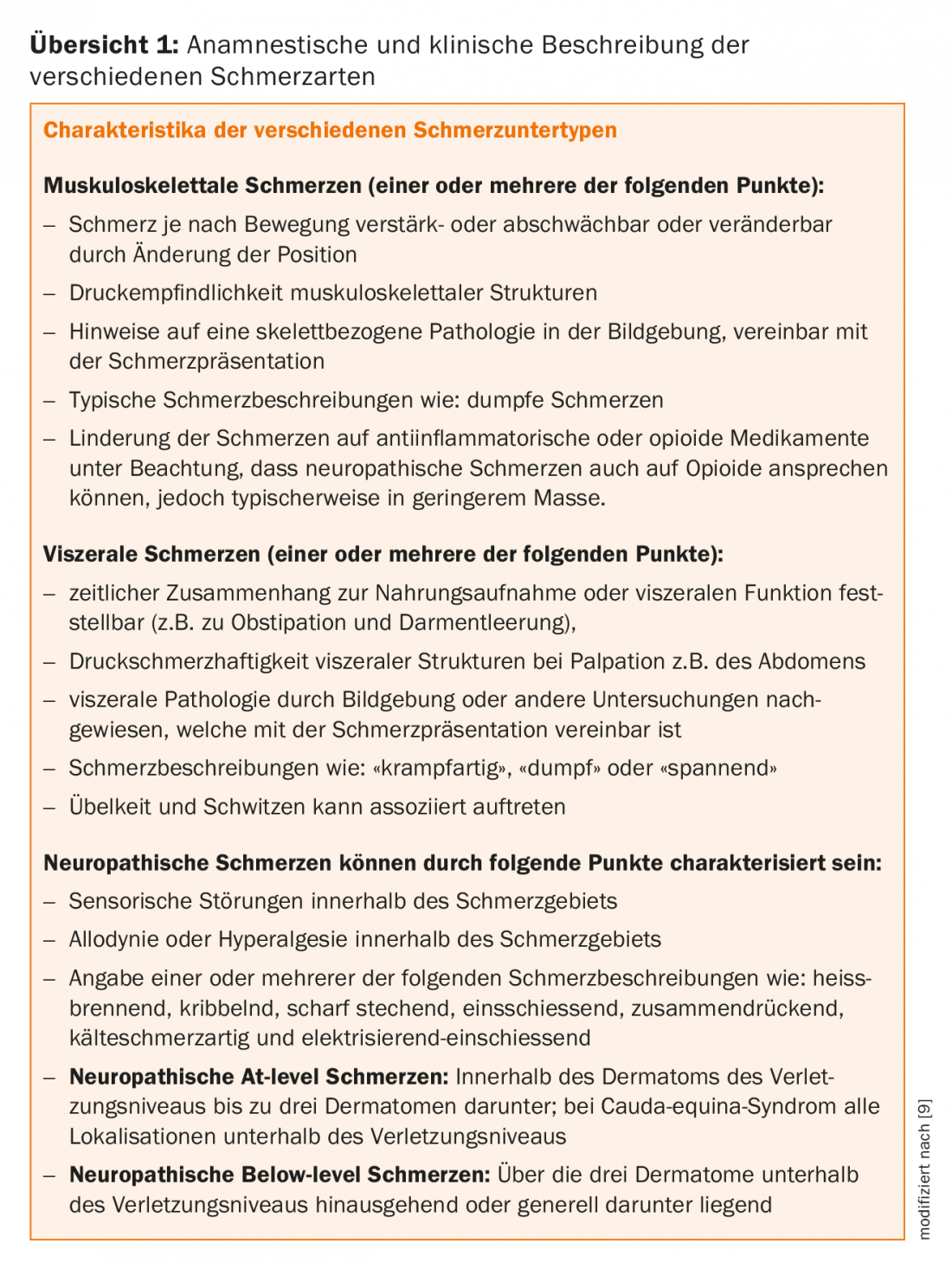

According to the classification of pain due to paraplegia updated in 2012 by the International Spinal Cord Society, we distinguish nociceptive, neuropathic, other defined pain syndromes, and unclassifiable pain [9]. (Tab. 1). Accordingly, nociceptive pain distinguishes musculoskeletal pain due to muscular, bony, or joint pathologies, visceral pain due to diseases and dysfunctions of internal organs, and other nociceptive pain such as headache due to autonomic dysreflexia. Pain due to spasticity is also categorized as nociceptive pain. In the group of neuropathic pain, on the one hand, neuropathic pain due to the nerve injury, which is directly related to the spinal cord lesion or the lesion of the cauda equina, is distinguished from neuropathic pain, on the other hand, which is present independently of the aforementioned lesions. The former are divided into neuropathic pain at the level of injury (At-level spinal cord injury pain) and neuropathic pain below the level of injury (Below-level spinal cord injury pain). Neuropathic pain independent of paraplegia, such as carpal tunnel syndrome, trigeminal neuralgia, diabetic polyneuropathy, and others, is referred to as “other neuropathic pain.” Defined pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome or colon irritabile are included in the so-called other pain syndromes. Finally, it is not always possible to classify the pain syndrome etiologically. In this case, the pain syndrome is referred to as “unattributable pain” [9,10]. The clinical characteristics used to distinguish the above pain types are shown in Overview 1.

Pain diagnostics in paraplegic patients

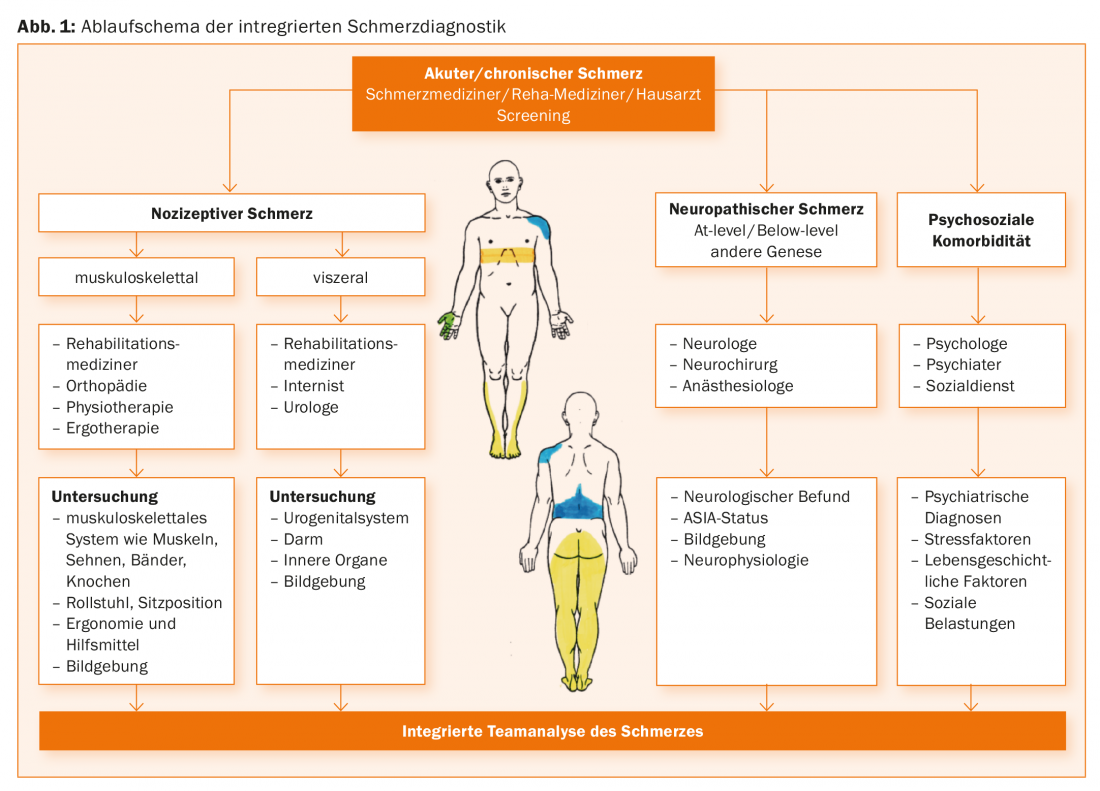

For a detailed account of the diagnostic steps, please refer to the literature [10]. As detailed below, interdisciplinary multimodal pain management also includes integrated pain diagnostics across teams [11]. A diagnostic algorithm is shown in Figure 1. Accordingly, anyone involved in the care of paraplegic patients, ideally a pain physician, should consider the presence of different types of pain based on the clinical characteristics presented in Overview 1 and, according to the suspected diagnoses of nociceptive or neuropathic pain, should involve the individual disciplines, step by step, depending on the clinical presentation. Clinically, the pain locations (pain drawing is useful), information on the pain character, pain intensity, diurnal course or dependence on physical activity and organ functions should be recorded. In the end, ideally, all the physicians and therapists involved should discuss the results of the examination together and make diagnoses that everyone on the team can essentially support.

Nociceptive pain, as defined by the International Association for Study of Pain (IASP) [12], results from activation of nociceptors due to actual or impending damage to non-neuronal tissue. Here, in contrast to neuropathic pain, there is normal function of the somatosensory system. Depending on the clinical picture, rehabilitation physicians, orthopedists, internists, urologists, physiotherapists and occupational therapists should be involved in the diagnosis in order to uncover the causes of the musculoskeletal system such as muscles, tendons, ligaments and bones. Likewise, an evaluation of the wheelchair and its ergonomics, including the seating position, is often necessary. Regarding the visceral system, the examination of the urogenital system, the intestinal system and the internal organs plays a role. In general, imaging techniques should also be included.

Neuropathic pain is defined by the IASP as pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory system [12]. A grading scheme is recommended for the diagnosis of neuropathic pain [13], which is available in an adapted form for the diagnosis of neuropathic pain due to paraplegia [14]. Here, the presence of paraplegia and pain at or below the level of injury is required anamnestically, evidence of a lesion of the spinal cord or cauda equina is required apparatively, and the exclusion of other causes of pain is required differentially. If only the anamnestic information such as history of paraplegia and pain at or below the level of injury is fulfilled, a possible neuropathic pain is present. In addition, if all of the following diagnostic criteria are met, such as demonstration of sensory positive or negative signs, apparative evidence of a lesion of the spinal cord or cauda equina, and exclusion of other causes of pain, a definite neuropathic pain is present. If only two of the three criteria mentioned are met, only probable neuropathic pain due to paraplegia can be diagnosed.

As mentioned above, the level of injury plays an important role in the classification of neuropathic pain in paraplegia. The neurological level of injury is defined here as the most caudal segment of the spinal cord with normal sensitivity to light touch and pointed sensation and normal motor function [15]. Accordingly, neuropathic pain at the level of injury (at-level spinal cord injury pain) is referred to when it occurs in the dermatome of the neurological level of injury, including the spinal cord. up to three of the underlying dermatomes. On the other hand, neuropathic pain below the level of injury (below-level spinal cord injury pain) is referred to when the pain extends more than three dermatomes below the level of injury or is generally below it. While neuropathic pain at the level of injury can be of both central neuropathic origin in spinal cord injury and peripheral neuropathic origin in, for example, traumatic nerve root damage at the level of injury, neuropathic pain below the level of injury is, by definition, always centrally generated neuropathic pain. Neuropathic pain in cauda equina syndrome represents a special form, since it corresponds to a peripheral neuropathic cause of pain due to nerve root damage of the cauda equina and is therefore classified by definition in the group of neuropathic pain at injury level, even if the pain extension is found beyond three segments below the neurological injury level [9]. The appearance of neuropathic pain later than one year after lesion or the change of the pain syndrome after a stable interval, then possibly also associated with a change of the neurological status, may be an expression of syringomyelia or other spinal pathology. In this case, imaging should be performed in any case, if suitable, by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). If necessary, it may be necessary to involve neurosurgeons in the diagnosis here. Syringomyelia is clustered at a mean of 15 years after trauma, predominantly in complete paraplegia and at the level of the cervical spine [16].

Neurophysiological and instrumental diagnostics

According to the previously mentioned diagnostic scheme, the diagnosis of spinal cord or cauda equina lesion is standardly made by MRI [17]. Here, in most cases, lesions can be detected in both patients with and without neuropathic pain due to paraplegia. In this case, clinical neurophysiology is of secondary importance in the diagnosis of neuropathic pain, since patients without neuropathic pain also show pathological findings. Electrophysiologic studies can complement the clinical examination and improve the diagnosis of paraplegia. These include somatosensory evoked potentials (SEP) as a test for posterior cord function, laser evoked potentials (LEP) and contact heat evoked potentials (CHEPS] as a test for anterior spinothalamic tract function, motor evoked potentials after transcranial magnetic stimulation as a test for the corticospinal tract, and sympathetic skin response as a test of the sympathetic pathways of the spinal cord [18].

As explained earlier, the diagnosis of neuropathic pain involves examination of the somatosensory system [13]. In the case of a questionably detectable lesion (e.g., due to metal artifacts on MRI) or an atypical lesion on MRI (lesion outside the sensory pathways), the use of special procedures available only in centers, such as LEP and quantitative sensory testing (QST), can support the diagnosis of neuropathic pain due to paraplegia [19]. Quantitative sensory testing creates a profile regarding sensory positive or negative phenomena [20]. Using QST, it has been shown that the development of neuropathic pain due to paraplegia is associated with the presence of increased sensitivity such as Pinprick hyperalgesia and allodynia [21,22], so QST may be able to identify patients at risk for neuropathic pain early.

Regarding the extensive mechanisms in the development of neuropathic pain due to paraplegia, we refer to [10].

Psychological factors play a central role in pain processing according to the bio-psycho-social model of disease [23] [24] . Accordingly, factors such as pain catastrophizing, pain-related anxiety, tension and avoidance of pain, and helplessness can lead to pain intensification and poorer pain coping. Factors that may reduce pain intensity and improve pain management include self-efficacy, pain management strategies, readiness to change, and pain acceptance. The involvement of the mentioned factors could also be confirmed for patients with chronic pain in paraplegia [3,25,26]. To evaluate the above psychological factors that may contribute to pain chronification or maintenance, a psychological evaluation should always be performed when the same are suspected. Evidence of relevant accompanying psychosocial factors may include depressive symptoms, appetite disturbances, low motivation or participation regarding daily activities, evidence of catastrophizing or bias regarding pain diagnosis, anxiety and panic symptoms, sleep disturbances, lack of family support, or evidence of alcohol, drug, or medication abuse or dependence [27].

Interdisciplinary multimodal therapy approach

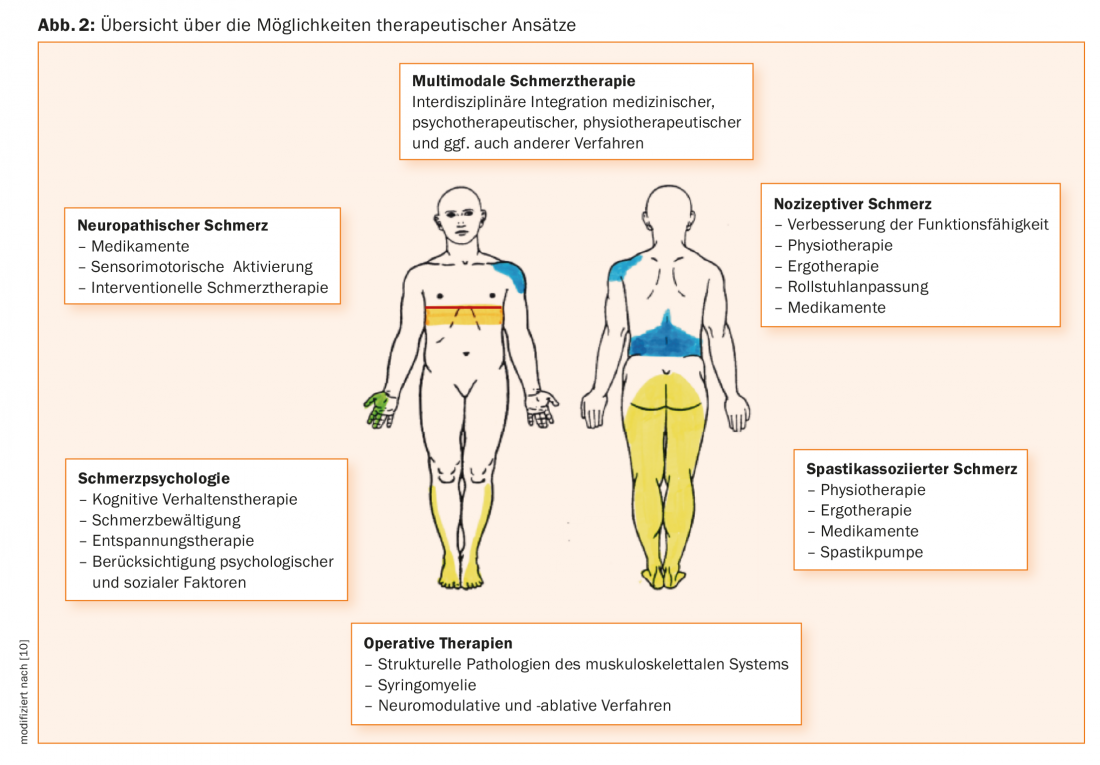

In accordance with the bio-psycho-social model of disease [23], an interdisciplinary multimodal therapeutic approach has become established in the treatment of chronic pain [11]. This involves a cross-team integrated approach including medical, physical therapy, psychological and other specialties. At the core of this approach are regular team meetings and structured interprofessional communication. This approach can take place in an individual patient setting, where all participating physicians and therapists treat the patient on the basis of individual appointments, or in the context of firmly established group programs. At best, a paraplegic with pain should be treated at a center with appropriate expertise. In contrast, an outpatient, well-coordinated team of individual therapists can also achieve good results with good communication.

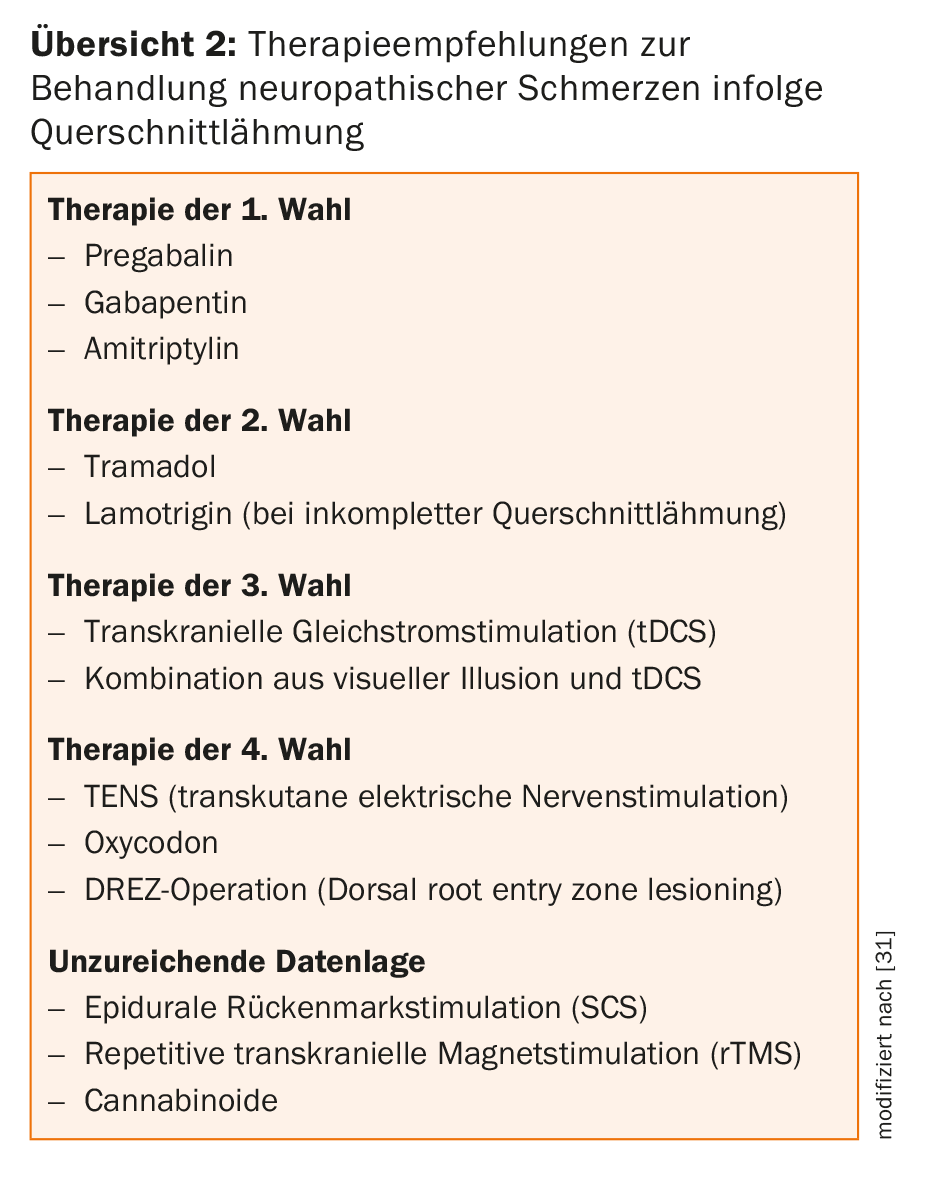

Because pain occurs early in patients with paraplegia and tends to persist, early treatment is recommended [28]. An interdisciplinary therapeutic approach is considered in a recent review [29]. Overview 2 gives an overview of current therapy options, which should be applied in an interdisciplinary team.

Medical therapy

Antinociceptive drug therapy: drug therapy for nociceptive pain includes nonopioid analgesics (e.g., acetaminophen, metamizole, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAR]) and also opioids. According to a therapy guideline for patients with chronic back pain without paraplegia, however, such drugs are only a supportive therapy option and should be reviewed with regard to effect and side effect every four weeks or with regard to therapy continuation every three months [30]. When pain and spasticity interact, efforts should also be made to optimize spasticity therapy. For visceral pain related to bowel function, optimization of bowel movements using laxatives would be considered.

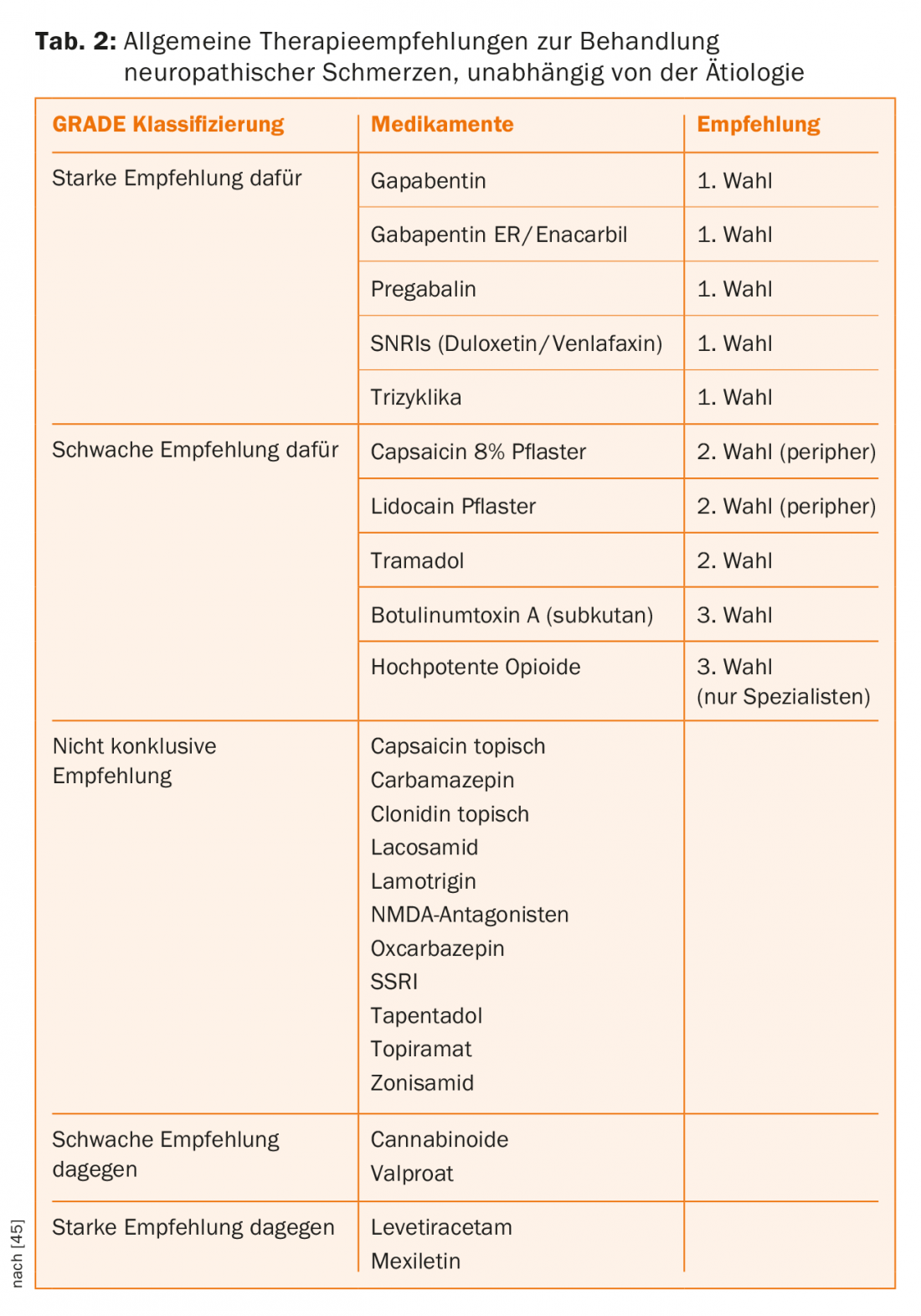

Antineuropathic drug therapy: drug therapy for neuropathic pain due to paraplegia is summarized in a recent guideline [31]. Here, pregabalin, gabapentin, and amitriptyline are recommended as first-line medications, and tramadol and lamotrigine are recommended as second-line medications, the latter only in cases of incomplete paraplegia. Opioids are considered to be the fourth-line therapy (Table 2). If no success can be achieved with these drug options, it is permissible to fall back on the general therapy recommendations of the IASP (Table 2).

Interventional/neurosurgical pain management: regarding neuropathic pain due to paraplegia, the evidence for procedures such as epidural spinal cord stimulation (SCS), deep brain stimulation (DBS), motor cortex stimulation (MCS), dorsal root entry zone lesioning (DREZ) surgery, and myelotomy is limited and therefore these options cannot be generally recommended. In each individual case, experienced centers are required for an evaluation with regard to such procedures [31] (see also Overview 2).

Physiotherapy/Ergotherapy: Physiotherapeutic approaches are predominantly used in the therapy of nociceptive pain. The goals of physical therapy, depending on the clinical picture, may be the development of postural control, motion control or achievable trunk control, treatment of muscular imbalances, and transfer adaptations. For example, therapy concepts according to Bobath or Vojta can be applied here. In particular, manual techniques and soft tissue treatments can have a positive effect. Closely related to the physiotherapeutic approaches is optimal wheelchair adaptation. The aim of this is the ergonomic adjustment of the wheelchair and the environment to suit the individual circumstances and requirements of the paraplegic. Optimizing the seat position leads to improved seat stability and thus to reduced incorrect loading in the shoulder, neck and back areas.

Psychological: In psychological pain management, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a commonly used method for psychosocial problems [32]. CT shows positive effects in patients with chronic pain syndromes including back pain on pain and behavioral variables [33]. In addition, positive influences of CT on psychological health could be demonstrated in persons with paraplegia [34]. Other procedures may include, for example, relaxation techniques, hypnosis, mindfulness-based methods, and positive psychology exercises [35–37], some of which have been studied in pain management in paraplegia.

Interdisciplinary multimodal therapy programs: The superiority of multidisciplinary therapies over single-disciplinary treatments has long been recognized [38]. Such therapeutic approaches can lead to improvements in pain and mood, return to work, and reduced health care costs. In particular, the effectiveness of interdisciplinary therapy programs based on cognitive behavioral therapy has been demonstrated [39]. Evidence is now available for interdisciplinary multimodal pain management programs for patients with chronic neuropathic pain due to paraplegia, demonstrating improvements in anxiety and depression, sleep quality, pain intensity, pain-related disability, participation, and pain coping [40–43].

Using our own interdisciplinary multimodal pain management program in pedestrians with chronic back pain [44], which included only one week but a high treatment intensity of 34 hours, we were able to demonstrate sustained positive effects on pain impairment, quality of life, pain-related disability, depression, and pain acceptance for up to one year. We have now established such a weekly program for paraplegics with chronic pain, which is currently being evaluated. The focal points of this program essentially correspond to those of the above-mentioned studies on paraplegia, such as medical education on paraplegia- or pain-specific issues, physiotherapy of nociceptive pain and spasticity, medical training therapy, mindfulness, occupational therapy with regard to sitting position, wheelchair adaptation and ergonomics, as well as psychological content such as the basics of pain psychology, pain acceptance, stress management, relaxation therapy and others (Fig. 3).

Take-Home Messages

- Due to the occurrence of different types of pain and pain mechanisms within the bio-psycho-social model of disease, pain management in patients with paraplegia is particularly challenging.

- According to the bio-psycho-social model of disease, an interdisciplinary multimodal therapeutic approach is recommended in the treatment of chronic pain.

- The superiority of multidisciplinary therapies over single-disciplinary treatments has long been recognized. In particular, the effectiveness of interdisciplinary therapy programs based on cognitive behavioral therapy has been demonstrated.

Literature:

- Rubinelli S, Glassel A, Brach M: From the person’s perspective: Perceived problems in functioning among individuals with spinal cord injury in Switzerland. J Rehabil Med. 2016; 48(2):235-243.

- Siddall PJ: Management of neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury: now and in the future. Spinal cord. 2009; 47(5): 352-359. Epub 2008/11/13.

- Muller R, Landmann G, Bechir M, et al: Chronic pain, depression and quality of life in individuals with spinal cord injury: mediating role of participation. J Rehabil Med 2017; 49(6): 489-496. epub 2017/06/10.

- Siddall PJ, McClelland JM, et al: A longitudinal study of the prevalence and characteristics of pain in the first 5 years following spinal cord injury. Pain 2003; 103(3): 249-57. epub 2003/06/07.

- Michailidou C, Marston L, De Souza LH, Sutherland I: A systematic review of the prevalence of musculoskeletal pain, back and low back pain in people with spinal cord injury. Disability and rehabilitation. 2014; 36(9): 705-715. Epub 2013/07/12.

- Bossuyt FM, Arnet U, et al: Shoulder pain in the Swiss spinal cord injury community: prevalence and associated factors. Disability and rehabilitation 2018; 40(7): 798-805. epub 2017/01/14.

- Andresen SR, Biering-Sorensen F, et al: Pain, spasticity and quality of life in individuals with traumatic spinal cord injury in Denmark. Spinal cord 2016; 54(11): 973-979. epub 2016/11/05.

- Finnerup NB: Neuropathic pain and spasticity: intricate consequences of spinal cord injury. Spinal cord 2017; 11(10): 70. epub 2017/07/12.

- Bryce TN, Biering-Sorensen F, et al: International spinal cord injury pain classification: part I. Background and description. March 6-7, 2009. spinal cord 2012; 50(6): 413-417. epub 2011/12/21.

- Landmann G, Chang EC, et al: [Pain in patients with paraplegia]. Pain 2017; 31(5): 527-545. Epub 2017/09/25.

- Kaiser U, Treede RD, Sabatowski R: Multimodal pain therapy in chronic noncancer pain-gold standard or need for further clarification? Pain 2017; 158(10): 1853-1859.

- Loeser JD, Treede RD: The Kyoto protocol of IASP Basic Pain Terminology. Pain 2008; 137(3): 473-477. Epub 2008/06/28.

- Finnerup NB, Haroutounian S, et al: Neuropathic pain: an updated grading system for research and clinical practice. Pai. 2016; 157(8):1599-1606.

- Finnerup NB: Pain in patients with spinal cord injury. Pain 2013; 154 Suppl 1(1): S71-76. Epub 2013/02/05.

- Kirshblum SC, Burns SP, et al: International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (revised 2011). The journal of spinal cord medicine 2011; 34(6): 535-546. Epub 2012/02/15.

- Krebs J, Koch HG, et al: The characteristics of posttraumatic syringomyelia. Spinal cord. 2015; 1(10): 218. epub 2015/12/02.

- Watts J, Box GA, et al: Magnetic resonance imaging of intramedullary spinal cord lesions: a pictorial review. Journal of medical imaging and radiation oncology 2014; 58(5): 569-581. epub 2014/07/06.

- Curt A, Ellaway PH: Clinical neurophysiology in the prognosis and monitoring of traumatic spinal cord injury. Handbook of clinical neurology 2012; 109: 63-75. Epub 2012/10/27.

- Landmann G, Berger MF, et al: Usefulness of laser-evoked potentials and quantitative sensory testing in the diagnosis of neuropathic spinal cord injury pain: a multiple case study. Spinal cord 2017; 55(6): 575-582. epub 2017/01/25.

- Rolke R, Magerl W, et al: Quantitative sensory testing: a comprehensive protocol for clinical trials. European journal of pain 2006; 10(1): 77-88. Epub 2005/11/18.

- Zeilig G, Enosh S et al: The nature and course of sensory changes following spinal cord injury: predictive properties and implications on the mechanism of central pain. Brain: a journal of neurology 2012; 135(Pt 2): 418-430. Epub 2011/11/19.

- Finnerup NB, Norrbrink C, et al: Phenotypes and predictors of pain following traumatic spinal cord injury: a prospective study. The journal of pain: official journal of the American Pain Society 2014; 15(1): 40-48. Epub 2013/11/26.

- Engel GL: The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977; 196(4286): 129-136. Epub 1977/04/08.

- Keefe FJ, Rumble ME, et al: Psychological aspects of persistent pain: current state of the science. The journal of pain: official journal of the American Pain Society 2004; 5(4): 195-211. Epub 2004/05/27.

- Jensen MP, Moore MR, et al: Psychosocial factors and adjustment to chronic pain in persons with physical disabilities: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011; 92(1): 146-160.

- Craig A, Tran Y, Middleton J: Psychological morbidity and spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal cord 2009; 47(2): 108-114. Epub 2008/09/10.

- Mehta S, Guy SD, Bryce TN, et al: The CanPain SCI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Rehabilitation Management of Neuropathic Pain after Spinal Cord: screening and diagnosis recommendations. Spinal cord 2016; 54 Suppl 1(1): S7-S13. Epub 2016/07/23.

- Finnerup NB, Jensen MP, et al: A prospective study of pain and psychological functioning following traumatic spinal cord injury. Spinal cord 2016; 54(10): 816-821. epub 2016/03/02.

- Loh E, Guy SD, et al: The CanPain SCI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Rehabilitation Management of Neuropathic Pain after Spinal Cord: introduction, methodology and recommendation overview. Spinal cord 2016; 54 Suppl 1(1): S1-6. epub 2016/07/23.

- Bundesärztekammer (BÄK) KBK, Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF): Nationale Versorgungsleitlinie Nicht-spezifischer Kreuzschmerz – Langfassung. www.versorgungsleitlinien.de, www.awmf.org

- Guy SD, Mehta S, Casalino A, et al: The CanPain SCI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Rehabilitation Management of Neuropathic Pain after Spinal Cord: Recommendations for treatment. Spinal cord 2016; 54 Suppl 1(1): S14-23. epub 2016/07/23.

- Butler AC, Chapman JE, et al: The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clinical psychology review. 2006; 26(1): 17-31. epub 2005/10/04.

- Ostelo RW, van Tulder MW, et al: Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2005; 25(1): CD002014. Epub 2005/01/28.

- Mehta S, Orenczuk S, et al: An evidence-based review of the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosocial issues post-spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation psychology 2011; 56(1): 15-25. epub 2011/03/16.

- Muller R, Gertz KJ, et al: Effects of a Tailored Positive Psychology Intervention on Well-Being and Pain in Individuals With Chronic Pain and a Physical Disability: A Feasibility Trial. The Clinical journal of pain 2016; 32(1): 32-44. epub 2015/02/28.

- Jensen MP, Barber J, et al: The effect of hypnotic suggestion on spinal cord injury pain. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation 2000; 14(1,2): 3-10.

- Kabat-Zinn J: Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Context: Past, Present, and Future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2003; 10(2): 144-156.

- Flor H, Fydrich T, Turk DC: Efficacy of multidisciplinary pain treatment centers: a meta-analytic review. Pain 1992; 49(2): 221-230. Epub 1992/05/01.

- Morley S, Eccleston C, Williams A: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain 1999; 80(1-2): 1-13.

- Norrbrink C, Lindberg T, et al: Effects of an exercise programme on musculoskeletal and neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury-results from a seated double-poling ergometer study. Spinal cord 2012; 50(6): 457-461. epub 2012/02/01.

- Heutink M, Post MW, et al: The CONECSI trial: results of a randomized controlled trial of a multidisciplinary cognitive behavioral program for coping with chronic neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. Pain 2012; 153(1): 120-128. epub 2011/11/22.

- Perry KN, Nicholas MK, Middleton JW: Comparison of a pain management program with usual care in a pain management center for people with spinal cord injury-related chronic pain. The Clinical journal of pain 2010; 26(3): 206-216. Epub 2010/02/23.

- Burns AS, Delparte JJ, et al: Evaluation of an interdisciplinary program for chronic pain after spinal cord injury. PM & R: the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation 2013; 5(10): 832-838. Epub 2013/05/21.

- Reck T, Dumat W, Krebs J, Lyutov A: [Outpatient multimodal pain therapy: Results of a 1-week intensive outpatient multimodal group program for patients with chronic unspecific back pain – retrospective evaluation after 3 and 12 months]. Pain 2017; 31(5): 508-515. Epub 2017/03/05. Outpatient multimodal pain management: results of a 1-week intensive outpatient multimodal group program for patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain – retrospective evaluation after 3 and 12 months.

- Finnerup NB, Attal N, et al: Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2015; 14(2): 162-173. epub 2015/01/13.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2018; 16(3): 16-24.