Just a few years ago, pregnant women were advised to avoid exercise during gestation. Even today, uncertainty sometimes prevails: Can sport lead to injuries or even premature abortion of the fetus? Does it affect the health of mother and child? A brief look at the effect of exercise on pregnancy.

Most people agree that a (normal) pregnancy is not a disease. However, the fact that this process is an extremely complex one, involving profound changes in the mother’s physiology, is impressively illuminated statistically: In Switzerland, one in four pregnancies does not end in birth.

So, was the recommendation of a few years ago to be inactive during pregnancy and even bed rest if there were the slightest problems the right thing to do after all? Can sports even be an issue during pregnancy? As we will see, the answer is clearly “yes”. And this is not only because women’s sports have become socially established, but also because appropriate physical activity – as in many pathological situations (hypertension, diabetes, etc.) – can even have extremely positive health effects on mother and child. The opposite is true: it is the inactivity of the expectant mother that increases the risk of complications!

Power peak in the first trimester

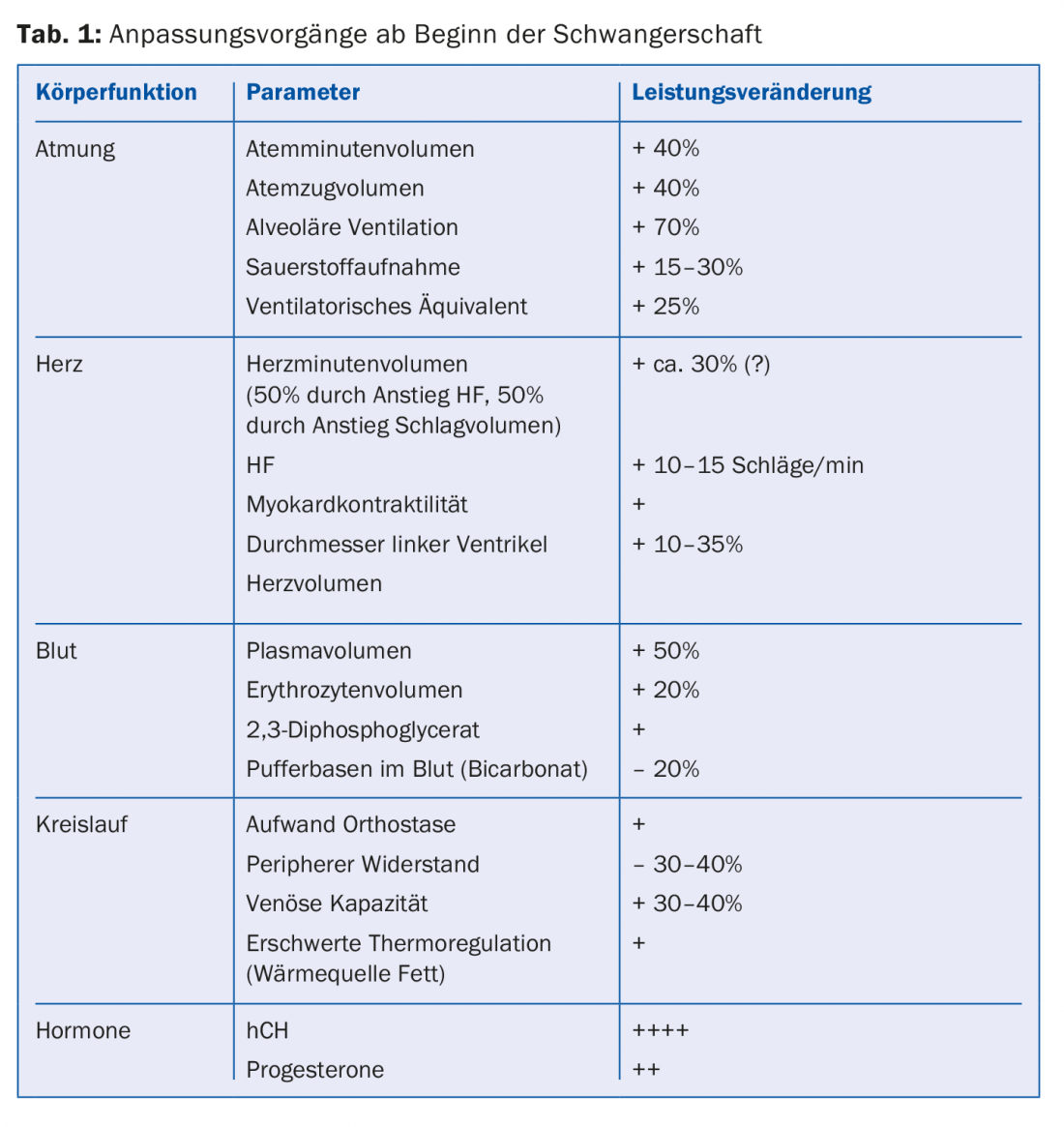

But let’s start at the beginning. It has always been the case that when a male spermatozoid enters a ruptured ovule in the female fallopian tube, both gametes give rise to an oocyte that will implant within a few days in the endometrium of the uterus, which has been prepared for this purpose by hormonal changes. A pregnancy has begun! But the future mother, most likely, does not know yet. The diagnosis of pregnancy is not always easy and clear in the first month, unless you resort to accurate laboratory tests. This means that the “affected” woman continues her usual activities as before and possibly also does her sports in the usual way. Actually, this is only logical – all the more so since the onset of pregnancy initiates quite interesting physiological adaptation processes right from the start (Table 1).

These changes are strongly reminiscent of the adaptations provoked during endurance training. Therefore, it is not surprising that some athletic women feel “like on clouds” in the early phase of their gestation and are able to perform at their best. Not only are these cardiovascular and metabolic adaptations beneficial to performance, but the hormonal constellation is also beneficial to performance in the early months of pregnancy, especially when deletive symptoms such as nausea and fatigue are not present.

Let’s take a closer look at human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). This representative of the glycoprotein hormone family is mainly produced in the placenta. Production begins about ten days after fertilization and increases sharply until the sixtieth day of gestation (doubling every other day). However, it is also found in non-pregnant women and men in weak doses. In men, hCG stimulates Leydig’s cells, where testosterone is produced. In females, hCG stimulates progesterone production, a hormone that appears to promote muscular extensibility and some joint laxity, but generally produces a rather lower level of muscular efficiency. This substance is on the doping list, but – understandably – is banned only for men. It is in this context that the presumably more anecdotal stories of the use of “transitional pregnancies” in young female athletes to improve their performance (termination of pregnancy just before the important competition) should be understood.

What about the risks?

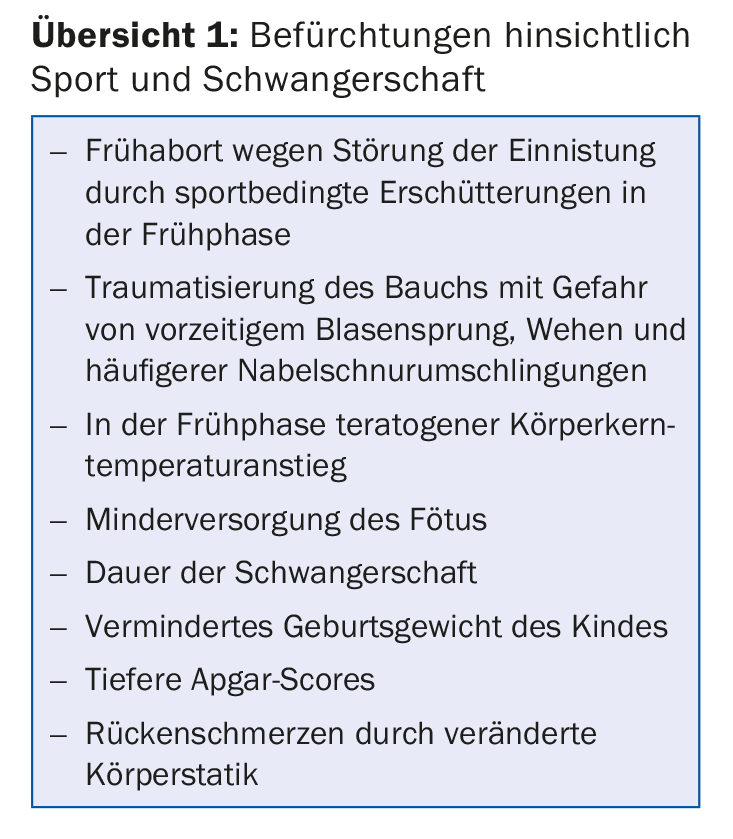

Concerns about negative effects of exercise on pregnancy abound, as Overview 1 shows.

Regarding premature abortion, which occurs in >10% of the normal population and in 80% in the first trimester: Is there actually an increased risk of losing the expectant child in this delicate first phase for an active woman compared to one who tends to be inactive? Studies suggest that physical activity in early pregnancy is generally associated with a slightly increased risk of miscarriage, especially with strength training and similarly intense exercise. However, it should be noted that the results should be taken with caution due to the study design. Their level of evidence is rated as low to moderate [1].

The issue of trauma must be assessed with common sense. Actually, the amniotic sac in utero is considered the best protected part of the body, but this does not mean that heavy blows (falls while skiing, impacts while playing soccer, etc.) cannot be harmful! Such activities are therefore rather inadvisable. A change in body statics due to the growing abdomen (and at most also due to the breasts) with resulting hyperlordosis and pelvic tilt as a compensatory mechanism is more likely to occur in later pregnancy. With weight gain and a general physical awkwardness, autoregulation with refraining from intense physical exertion usually occurs at this stage anyway.

During physical performance, such as during a marathon, the mother’s body temperature can rise significantly, which together with temperature control through sweating, coupled with intense skin blood flow, can trigger some problems: Transfer of temperature to the child (teratogenic in early pregnancy) and blood insufficiency of the uterus due to blood redistribution in favor of the working muscles and skin. Despite all this, meta-analyses [2] show that most of these mentioned fears are not scientifically provable and therefore not justified.

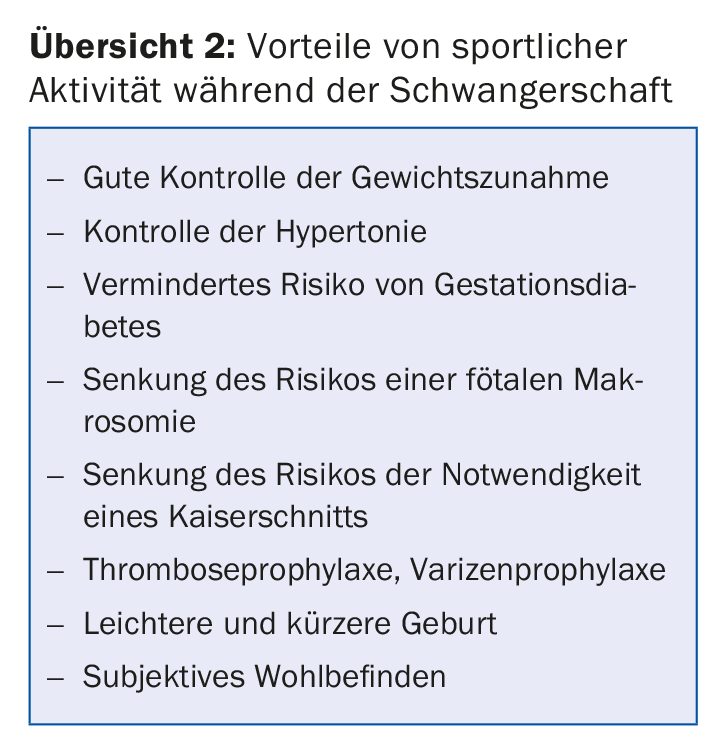

With regard to the positive aspects – summarized in overview 2 presented – there is enough literature [1], and thus it should be possible for the practitioner to convincingly advise a pregnant woman in the following sense: If a woman is healthy and has exercised regularly prior to her pregnancy, then physical training will usually bring more benefits than dangers to both her and the child. However, it is not advisable for a woman who has not practiced any sport to start an activity during gestation; pregnancy is not the right time to learn a new sport.

Conclusion

From a research and ethical point of view, the topic of “sport and pregnancy” is rather complex, but the available data show that sporting activity and pregnancy normally get along well. These optimistic conclusions are valid to some extent even for high-performance female athletes. And the message that exercise during pregnancy makes babies smart should be the “icing on the cake” on this issue: a Canadian study recently showed that healthy activity by the expectant mother also helps improve cognitive skills later in the child’s life.

Literature:

- Bø K, et al: Exercise and pregnancy in recreational and elite athletes: 2016 evidence summary from the IOC expert group meeting, Lausanne. Part 1: exercise in women planning pregnancy and those who are pregnant. Br J Sports Med 2016; 50: 571-589.

- Lokey EA, et al: Effects of physical exercise on pregnancy outcomes: a meta-analytic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1991; 23: 1234-1239.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(10): 7-8