They are more common than you think: around 10% of a general population suffer hypersensitivity reactions after drinking wine. Allergist Prof. Dr. med. Brunello Wüthrich explains different forms of wine intolerance as well as their etiological correlations and treatment options.

Shortly before my retirement from the University Hospital in June 2003, a couple came to see me in my consultation hours. They asked me if they were suffering from a “wine allergy”. The husband, Franz S., a 63-year-old merchant with no previous atopic disease, had suffered intermittently for several years from an itchy, rapidly transient generalized rash. Lately, he had noticed that after drinking red wine, headaches, itching and hives appeared. His wife, 60-year-old Martha, who had mild, non-allergic asthma, had been experiencing sneezing attacks, runny nose and asthma for years after drinking white wine (she disliked red wine) and especially after just one sip of sparkling wine. For both it was clear that there was a “wine allergy”. The extensive allergological clarification with inhalation allergens, molds (Botrytis cinerea), foods, and with prick tests for various types of wine was negative in both. Serum IgE levels were not elevated, and various allergen-specific IgE determinations were negative. Based on the history, I made a probable diagnosis of “histamine intolerance” in the husband and “sulfite intolerance with intrinsic asthma” in the wife. As a measure, I recommended Franz S. to take two tablets of a diamine oxidase preparation about half an hour before festive occasions with alcohol consumption. Martha S. should switch to “Schlumberger” sparkling wine, which contains only a minimal amount of sulfites (up to about 10 mg/l); in principle, sulfurization is permitted for quality sparkling wines and sparkling wines up to a sulfur dioxide content of 185 mg/l according to Regulation VO (EC) No. 1493/1999 (2005). Apparently, these recommendations were successful, because for years I have always received a bottle of “Brunello di Montalcino” as a gift before Christmas!

Wine allergies and intolerances

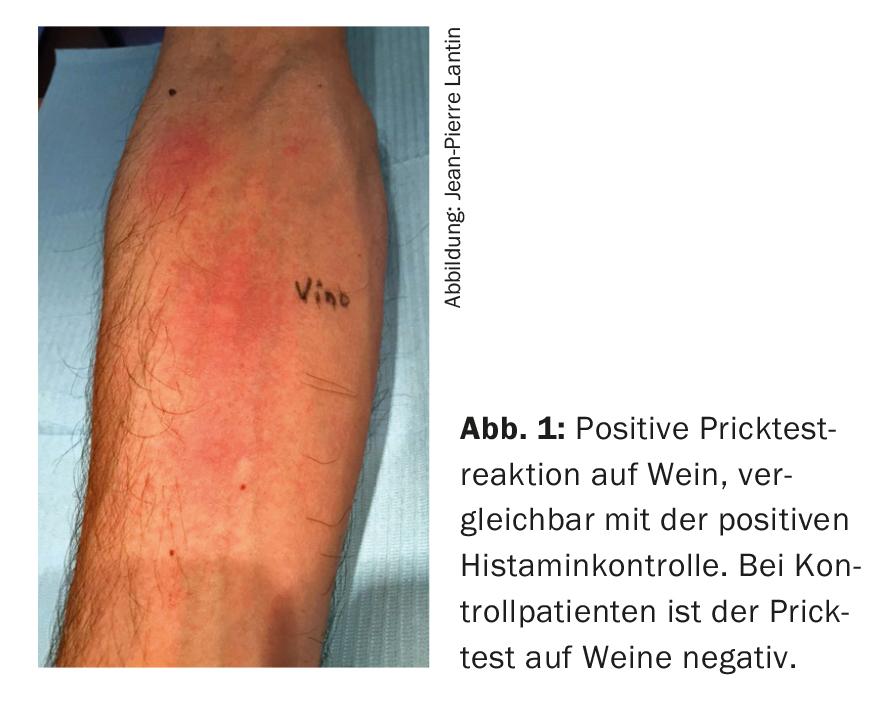

The frequency of hypersensitivity reactions after alcohol consumption (especially red wine) should not be underestimated: It is about 10% in a general population [1,2]. Pathogenetically, a distinction must be made between immunological, mainly IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions (wine allergies) and wine intolerances, in which no allergen-specific immune mechanisms are detectable [3]. If wine allergy is suspected, the prick test with the wine in question should be positive (Fig. 1). Potential allergens include proteins from the grape itself, particularly its major allergen, the lipid transfer protein Vit v 1, proteins and ingredients used in wine clarification (fish gelatin or isinglass, i.e., the swim bladder of the fish species Hausen), hen’s egg proteins, milk (casein) products, and gum arabic. Other allergens may include enzymes such as lysozyme, pectinase, glucanase, cellulase, glucosidase, urease and flavor enzymes. But also molds (here especially Botrytis cinerea, responsible for the noble rot of the wine), yeasts and proteins from insects that have contaminated the mash are possible. Type I allergic reactions have been described to non-organic ingredients such as ethanol, acetaldehyde and acetic acid as well as sulfites, although it was not possible to detect specific IgE in serum for these haptens [3].

In the following, only wine intolerance reactions, i.e. pseudoallergic reactions, are discussed. Boxes 1-2 provide a brief historical review of viticulture and the relationship between wine and health as propagated in ancient times.

Alcoholic fermentation and genetic hypersensitivity reactions.

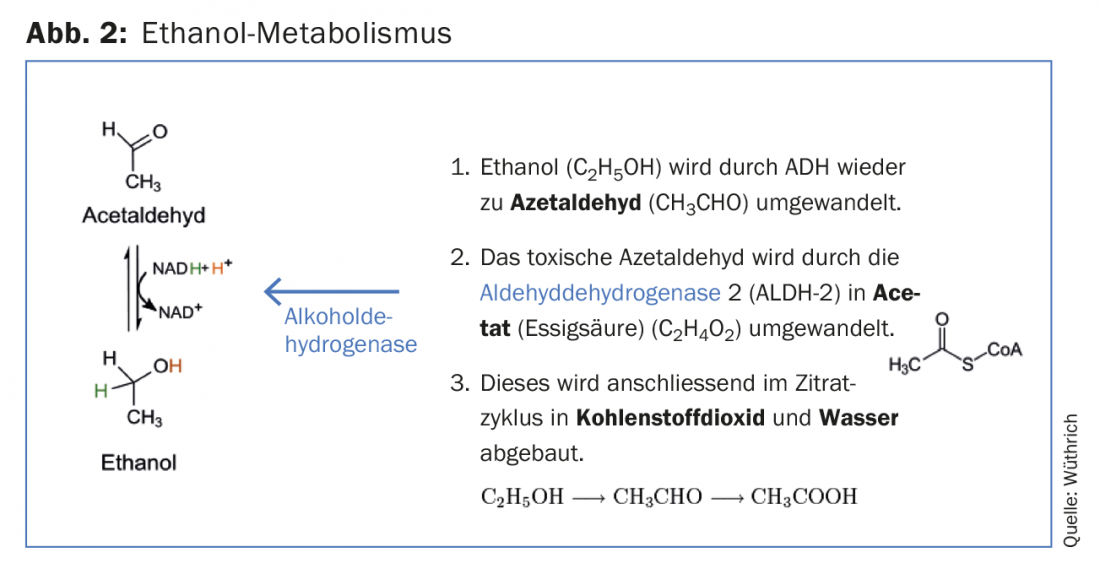

In the final step of alcoholic fermentation by yeast, acetaldehyde (ethanal) is converted to ethanol by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH). Alcohol breakdown in the liver occurs in three steps (Fig. 2).

Symptoms of poisoning after wine (flush syndrome) are due to enzymopathy. There is either a genetically determined high activity of the enzyme ADH, whereby a high amount of the toxic acetaldehyde is formed very quickly from ethanol, or a genetically determined deficit of the enzyme ALDH-2, whereby acetaldehyde cannot be detoxified sufficiently. 46% of Japanese and 56% of Chinese are affected by a polymorphism of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase 2. The mutant ALDH-2 can process acetaldehyde less effectively than the wild-type protein and is itself degraded more rapidly. This makes it easier for toxic acetaldehyde to accumulate in the body, leading to flush syndrome [3,4].

Wine intolerances

Ethanol, acetaldehyde and acetic acid, flavonoids (anthocyanidins and cathecins), sulfites, histamine and other biogenic amines are the main triggers of wine intolerance reactions (pseudoallergic reactions) [3].

Except for the genetic flush syndrome after ethanol, these anaphylactoid reactions, often in the form of urticaria, are nonallergic hypersensitivity reactions. Prick tests are negative. Diagnosis can only be made by oral provocation testing, preferably using the DBPCFC (double-blind placebo-controlled provocation) method [5].

Fusel oils: These are long-chain alcohols and other compounds, of which especially extract-rich wines contain more. They are broken down only slowly and have an anesthetic effect. They cause the “hangover”. Normally, wines contain only small amounts of it. But with unclean fermentation they can become a problem.

Tannin and flavonoids: Tannin consists of flavonoid phenols polymerized together, such as catechin, epicatechin, anthocyanins, etc. They are polymers whose monomeric units consist of phenolic flavans, mostly catechin (flavan-3-ol). Red wine contains phenolic flavonoids, which include anthocyanidins and catechins. They give the red wine its color. These flavonoids inhibit the enzyme catechol-O-methyltransferase and prolong catecholamine action. In addition, the enzyme phenolsulfone transferase (PST) is inhibited. This leads to the body being unable to detoxify certain phenols, which then enter the brain via the bloodstream and trigger migraines. Patients who consider red wine to be the trigger of their migraines actually have lower activities of the PST enzyme in their blood. Red wine tops the list of suspected foods in relation to wine intolerance. The fact that it is not the alcohol content, but components in the red wine, was verified in an English study by a blind test with 19 patients who stated that they were sensitive to red wine. Subjects received either 0.3 l of red wine or a vodka-lemonade mixture with the same alcohol content. The taste was masked by having to drink the iced drinks from a brown glass with a dark straw. Nine of the eleven red wine drinkers promptly reacted with a migraine attack, but none of the vodka drinkers. Five healthy comparison subjects tolerated the red wine without side effects [6,7]. The English researchers blame polyphenols for migraine attacks. Red wine sometimes contains more than 1 g/l (especially flavonoids such as catechins and anthocyanins), while white wine usually contains no more than 250 mg/l. This theory is supported by the observation that, in addition to red wine, chocolate in particular is cited as a trigger for migraine. Polyphenols account for as much as 12-18% of the dry matter of cocoa beans. Tannins, catechins and anthocyanins also play an important role here. However, other authors attribute migraine attacks to tyramine (reviewed in [8]) or to histamine in wine [9].

Sulphite tolerance

The sulfurization (SO2) of the wine – which was already practiced by the ancient Romans – prevents browning and the development of harmful microorganisms such as vinegar bacteria, wild yeasts and molds. Sulfites (EC No. 220-227) in wine must be declared since January 1, 2008 if the concentration is more than 10 mg/l SO2 (“contains sulfites” or “contains sulfur dioxide”). The EU maximum values for dry red wine are 160 mg/l, for sweet white wine 210 mg/l. Especially with white wine, allergy-like intolerance reactions are caused by the sulfite content [10]. Asthmatics, mostly of non-IgE-associated type and with unstable, poorly controlled asthma, are particularly sensitive. There is an irritation of the so-called irritant receptors of the respiratory tract by the sulfur dioxide formed in the stomach and thus bronchoconstriction. The patient Martha S. is a typical example.

Histamine intolerance

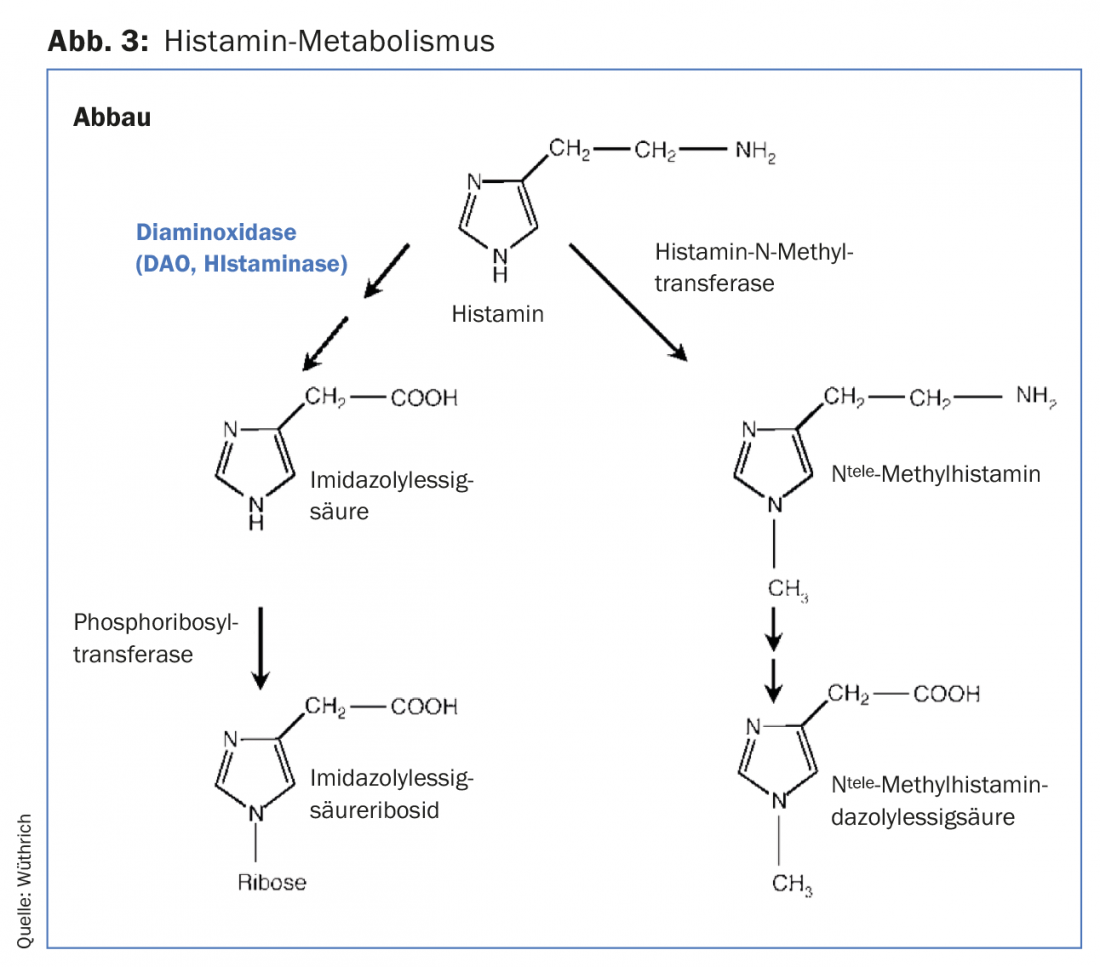

Biogenic amines such as histamine, tyramine, cadaverine, putrescine, spermine and spermidine are produced during wine, champagne and fruit juice production by malolactic fermentation, also known as biological acid degradation. Malolactic fermentation is a secondary fermentation; it follows the alcohol-producing primary fermentation. Oenococcus oeni is significant in winemaking, as are Lactobacillus spp, Pediococcus spp and yeasts. A higher concentration of histamine is due to poor cellar hygiene or uncontrolled malolactic fermentation. Secondarily, it is the grape varieties sensitive to powdery mildew that, as a self-protection, increase their content of biogenic amines or their degradation products (H2O2 and aldehydes) upregulate against pests. Histamine can be removed, but never completely, using bentonite. Also, the histamine content in the wines varies greatly. Rosé wines and white wines contain the least histamine. Champagne can sometimes have larger amounts of histamine [11]. The body is usually able to tolerate larger amounts of externally supplied histamine and other biogenic amines. Histamine is degraded in the gastrointestinal tract by the enzyme diamine oxidase (DAO) (Fig. 3). DAO is mainly found in the small intestine (terminal ileum), liver, kidneys and mast cells. It is continuously produced and released into the intestine. Therefore, in healthy humans, histamine can already be degraded to a large extent in the intestine, whereby DAO metabolizes not only histamine but also other biogenic amines (higher affinity). A whole range of complaints (sneezing attacks, gastrointestinal disorders, urticaria, sometimes migraine-like headaches) are observed in the histamine intolerance syndrome [11]. Patient Franz S. suffers from histamine intolerance.

Alcohol inhibits DAO activity and thus the degradation of histamine and other biogenic amines. It also increases the permeability of the intestinal walls so that histamine and other biogenic amines ingested with food or alcoholic beverage can enter the bloodstream and pass the brain barrier: The histamine binds to H3 receptors of the small brain vessels. As a result, vasodilation and headaches occur. This is also the reason why the combination of alcohol with histamine-rich foods (e.g. alcohol and cheese) in particular can lead to complaints in patients with histamine intolerance. Especially dangerous is the “buffet situation”, where abundant food and beverages are consumed, which contain high amounts of biogenic amines. In chronic symptomatology, in addition to exogenous and endogenous intake of biogenic amines, a genetic or acquired severe DAO deficit is decisive.

Summary and conclusions

Intolerance reactions after wine consumption (wine hypersensitivity) are quite common with an estimated prevalence of about 10%. The underlying pathomechanisms and etiological factors of wine hypersensitivity are manifold. After exclusion of enzymopathies (acetaldehyde dehydrogenase 2 deficiency), both allergic IgE-mediated reactions and nonimmunologic intolerance reactions occur. Most common are intolerance reactions to sulfites, especially after white wine consumption and in asthmatics, and to histamine and other biogenic amines, especially after red wine. In order to be able to recommend suitable prophylactic measures to the patient, the allergist should subject his patients to a careful assessment. It is important to provide consistent pharmacotherapy for existing asthma or rhinitis and to dispense emergency medication.

For festivities, a sparkling wine with low histamine and sulfite content (e.g. “Schlumberger”), and in case of histamine intolerance, a DAO substitution (Daosin®) can be recommended [3,12].

Literature:

- Linneberg A, et al: Prevalence of self-reported hypersensitivity symptoms following intake of alcoholic drinks. Clin Exp Allergy 2008; 38: 145-151.

- Vally H: Allergic and asthmatic reactions to alcoholic drinks: a significant problem in the community (Editorial). Clin Exp Allergy 2008; 38: 1-3.

- Wüthrich B: Wine allergies and intolerances. Allergology 2011; 34: 427-436.

- Harada S, et al: Aldehyde dehydrogenase deficiency as cause of facial flushing reaction to alcohol in Japanese. Lancet 1981; 2(8253): 982.

- Schwarzenbach-Stöckli S, Bircher AJ: Alcohol intolerance in hypersensitivity to acetaldehyde and acetic acid. Allergology 2007; 30(4): 139-141.

- Littlewood JT, et al: Red wine as a migraine trigger. In: Clifford Rose FC, ed: Advances in headache research: proceedings of the 6th International Migraine Symposium. London: J. Libbey 1987; 123-127.

- Littlewood JT, et al: Red wine as a cause of migraine. Lancet 1988; 1: 558-559.

- Panconesi A: Alcohol and migraine: trigger factor, consumption, mechanisms. A review. J Headache Pain 2008; 9: 19-27.

- Wantke F, et al.: Histamine in wine. Bronchoconstriction after a double-blind placebo-controlled red wine provocation test. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 1996; 110: 397-400.

- Vally, H, Thompson PJ: Role of sulfite additives in wine induced asthma: single dose and cumulative dose studies. Thorax 2001; 56: 763-769.

- Jarisch R, ed: Histamine intolerance – histamine and seasickness. 2nd rev. ed. and ed. ed. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme 2004.

- Komericki P, et al: Histamine intolerance and orally administered diamine oxidase: results of a multicenter study. JDDG 2009; 7 Suppl. 4: 203-204.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2018; 28(6): 36-39

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2018 Special Edition (Anniversary Issue), Prof. Brunello Wüthrich