Therapy concepts in the treatment of keloids should be determined individually. A combination of multiple therapy modalities is recommended. Visible treatment success should be seen after three to six months, otherwise the therapy must be adjusted. The best successes with conservative therapy are achieved with scars that are still “active”. As a rule, surgical interventions should be performed at the earliest one year after scar formation, only after conservative options have been exhausted, and always in combination with soft X-ray therapy.

Injuries and inflammations of the skin may be accompanied by scarring. Due to a cause that has not yet been conclusively clarified, pathological, excessive scarring occurs in some cases.

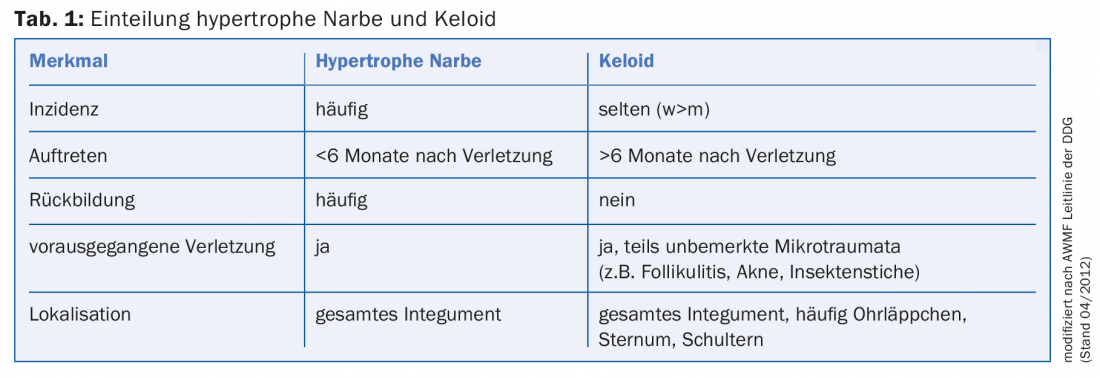

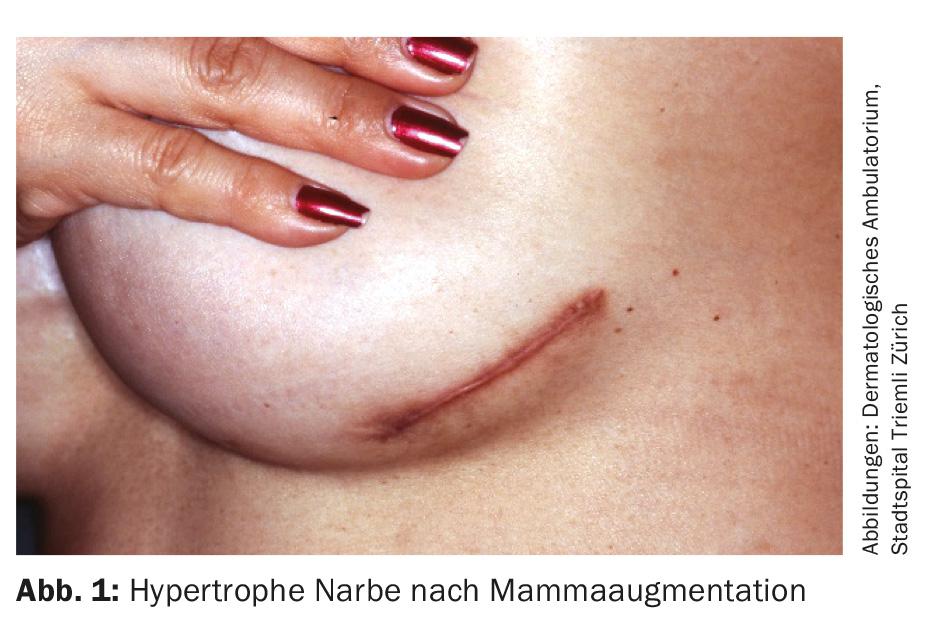

A distinction is made here between the hypertrophic scar (Fig. 1) and the keloid (Fig. 2) . While the hypertrophic scar is limited to the area of the original injury, the keloid grows beyond the original lesion. Additional diagnostic criteria are summarized in Table 1 .

Pathogenesis

The etiology is unclear. In the context of a prolonged inflammatory phase, the proliferation of fibroblasts and the concomitant increased synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins lead to an excessive formation of scar tissue.

Unlike hypertrophic scars, keloids are known to have a genetic predisposition. Both autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive modes of inheritance have been described. The incidence of keloids increases with increasing skin pigmentation (15-20-fold increased in Asians and black Africans) and decreases with age.

Symptoms

The aesthetic impairment is often in the foreground. Patients also frequently complain of sensitivity to touch, pain and excruciating itching. Functional limitation can be observed especially in the case of scars in the area of joints. Depending on the severity and localization, the scars can be psychologically very stressful for the patient.

Diagnostics

In most cases, this is a visual diagnosis. If clinical findings are unclear (e.g., increased vascular markings, indistinct borders, and ulceration) , basal cell carcinoma (Fig. 3), squamous cell carcinoma, or dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans should be considered as differential diagnoses. In this situation, a biopsy must be performed, and keloid formation may be additionally triggered by this.

Prevention

The risk of excessive scar formation can be reduced by tension-free wound closure taking into account the skin cleavage lines. Prolonged inflammatory conditions, for example due to contamination (e.g. foreign bodies) or wound infections, should be avoided. The use of absorbable, subcutaneous and intracutaneous suture material promotes the formation of hypertrophic scars. This should be taken into account especially for operations on the face. In any case, the patient must be educated about the need for adequate postoperative sun protection.

Therapy

Basically, hypertrophic scars and keloids are benign in nature, although the latter could also be called semimalignant due to their destructive growth into healthy skin. The therapy is primarily based on the needs (e.g. aesthetics), or complaints (e.g. itching, pain, contractions) of the patient. Therapy concepts should be determined individually, depending on the extent, localization, age and type of scar, as well as the patient’s skin type. Combination therapy is useful in most cases. Visible treatment success should be seen after three to six months, otherwise the therapy must be adjusted. Photo documentation is useful for assessment. Furthermore, different scales are available nowadays: Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS), Patient Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS) and Visual Analog Scale (VAS). Among other things, the height, consistency, pigmentation and symptomatology (itching/pain) of the scar are quantified.

Scar ointments: The use of scar ointments containing heparin and/or onion extract is a well-tolerated therapeutic option. It is postulated that both collagen production and inflammatory processes are inhibited by the ingredients contained. The therapy should be started shortly after thread traction and should be carried out over several months. The ointment must be massaged in several times a day for a few minutes, as the massage may be as important as the actual active ingredient.

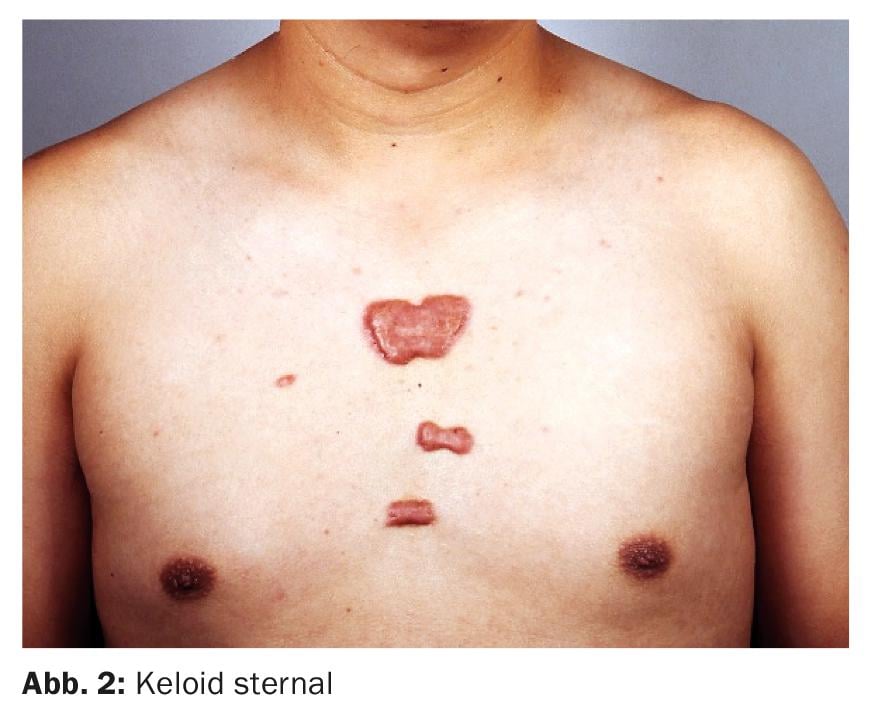

Silicone and compression bandages: The use of occlusive-acting silicone dressings is possible, especially for large-area lesions or after surgical excision. These should be worn 12-24 hours a day for one to two years. Alternatively, pressure treatment with compression bandages (10-40 mmHg) can be applied all day for 6-24 months. In the case of keloids in the area of the ear helix and lobules, clips or epithetic templates can be used (Fig. 4) . This should be started immediately after wound healing is complete. Compression therapy seems to be particularly effective in children. Both therapeutic approaches require a high level of compliance on the part of the patient.

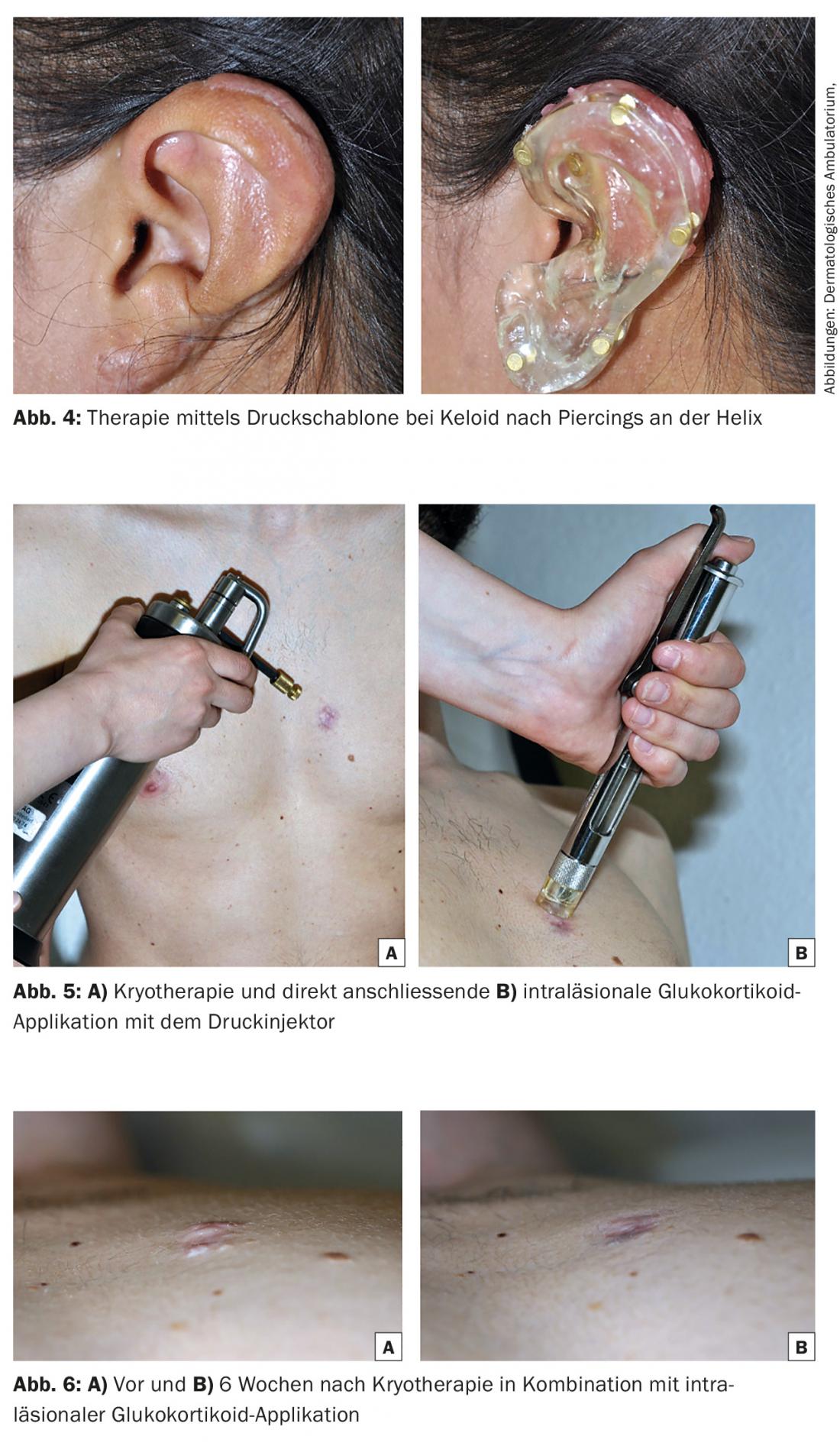

Intralesional glucocorticoid injection: for small and hypertrophic lesions, intralesional glucocorticoid injection with initially increasing dosage (e.g., triamcinolone acetonide [TAC] 10-40 mg/ml, diluted 1:2 to 1:4 with NaCl or lidocaine) every four to six weeks is an appropriate therapy. Especially after immediately preceding cryotherapy (complete freezing of the tissue), this method is very effective (Fig. 5 and 6A and B). The glucocorticoid can be introduced with a Luerlock syringe or a pressure injector. During administration, it should be noted that injections that are too superficial can lead to hypopigmentation and the formation of telangiectasia, while injections that are too deep into the subcutis can lead to atrophy. Information should be provided about possible blistering following icing. The response rate, especially for keloids, is 50-100%. The best results are achieved with scars that are still “active”, itchy, painful, reddened. If postoperative keloid formation is suspected, a glucocorticoid can be injected as a preventive measure immediately after surgery (initially 1×/week, in the course 1×/month). However, prior cryotherapy should then be avoided. Topical application of glucocorticoids has no effect.

5-Fluorouracil and bleomycin: In therapy-resistant keloids, intralesional injection of 5-fluorouracil (50 mg/ml every one to two weeks), in combination with glucocorticoids if necessary, may be considered. The application is off-label. Blood samples should be taken at regular intervals to rule out anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and infection. Bleomycin (1.5 IU/ml, 2 ml/cm2 skin) is available as an alternative effective product. This is inserted into the scar with a needle after application.

Imiquimod and interferon: In the current literature, topical application of imiquimod and intralesional application of interferon (in combination with glucocorticoids) are increasingly discussed. The effect of both therapies is based on interferon-mediated inhibition of collagen synthesis. Few studies prove the efficacy of these substances, and their use is not currently recommended, not least because of their high cost.

Surgical excision: If the conservative treatment options are not promising, surgical excision can be considered at the earliest one year after scar formation (possibly earlier in case of functional and esthetic limitations). This must always be combined with subsequent therapy, primarily soft X-ray radiation. In the case of hypertrophic scars, it is better to wait, as spontaneous regression is frequently observed. Especially in the case of keloids, the patient must be informed about the risk of postoperative recurrence, possibly even accompanied by a larger scar. In addition to scar excision, tension relief of the affected area by Z-/W- or appropriate flap plasty is another option for scar surgery.

Laser application: As an alternative to surgery, laser application has become increasingly popular in recent years. A distinction is made between ablative (CO2, Er:YAG lasers) and non-ablative (flash lamp-pumped pulsed dye laser [FPDL]) procedures. Ablative lasers are most suitable for leveling inactive, hypertrophic scars. In keloids, caution is advised, especially with monotherapy, due to the increased risk of recurrence. The FPD laser targets the vascular structures in the scar tissue, creating necrosis. This leads mainly to a reduction in erythema. Treatments should be repeated approximately every six weeks until desired results are obtained.

Soft X-ray radiation: After surgery or laser therapy, soft X-ray radiation is suitable as adjuvant therapy for recurrence prophylaxis. If possible, the first session should take place on the day of surgery. Ionizing radiation has an antiproliferative and anti-inflammatory effect, and with adequate radiation dose (total dose 9-12 Gy in 6-10 units every one to three days) wound healing is not delayed.

Further reading:

- Poetschke J, et al: Current Options for the Treatment of Pathological Scarring. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2016 May; 14(5): 467-477.

- Shah VV, et al.: 5-Fluorouracil in the Treatment of Keloids and Hypertrophic Scars: A Comprehensive Review of the

- Literature. Dermatol Ther Heidelberg 2016 Jun; 6(2): 169-183.

- Jones CD, et al: The Use of Chemotherapeutics for the Treatment of Keloid Scars. Dermatology Reports 2015 May 21; 7(2): 5880.

- Arno A, et al: Up-to-Date Approach to Manage Keloids and Hypertrophic Scars: A Useful Guide. Burns 2014 Nov; 40(7): 1255-1266.

- Rabello FB, et al: Update on hypertrophic scar treatment. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2014 Aug; 69(8): 565-573.

- Trisliana PA, et al: Recent Developments in the Use of Intralesional Injections Keloid Treatment. Arch Plast Surg 2014 Nov; 41(6): 620-629.

- Nast A, et al: German S2k guidelines for the therapy of pathological scars (hypertrophic scars and keloids). J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2012 Oct; 10(10): 747-762.

- Fearmonti R, et al: A Review of Scar Scales and Scar Measuring Devices. Eplasty 2010 Jun 21; 10:e43.

- Naeini FF, et al: Bleomycin tattooing as a promising therapeutic modality in large keloids and hypertrophic scars. Dermatol Surg 2006 Aug; 32(8): 1023-1029.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2016; 26(4): 12-16