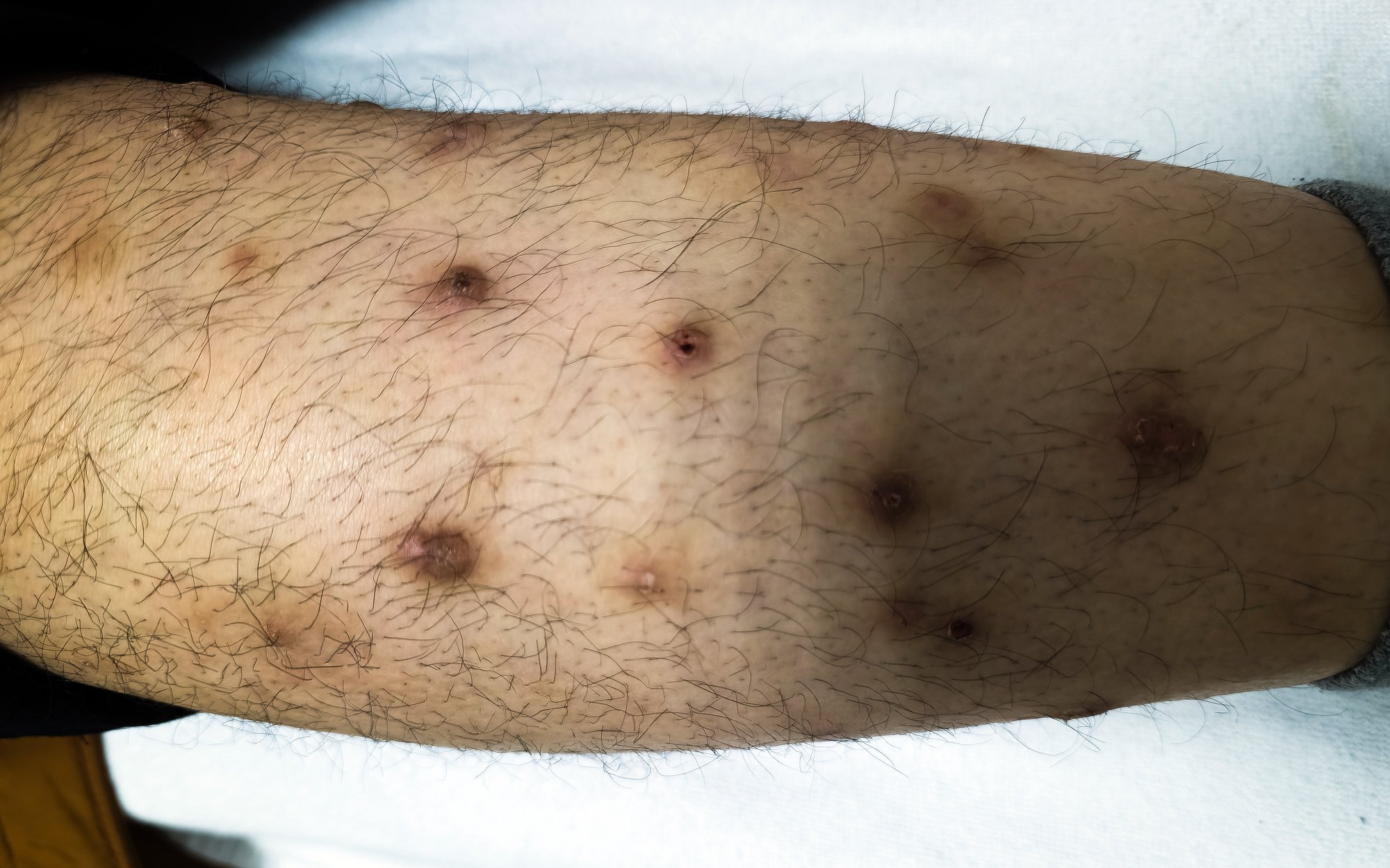

Findings from interdisciplinary pain research are also relevant to everyday dermatological practice. As with other indications, effects and side effects should be carefully weighed in this context (e.g., risk of dependence).

Pain conditions relevant in the dermatological setting are mostly nociceptive (triggered by mechanical, thermal and/or chemical noxae) or neuropathic (e.g. in the context of postzoster neuralgia and pyoderma gangraenosum), although a combination is also possible (“mixed pain”) [1,2]. At this year’s AAD Annual Meeting, Prentiss Lawson, MD, Assistant Professor at the University of Alabama (Birmingham/USA), provided information on practice-relevant findings from interdisciplinary pain research.

If opioids are prescribed for longer than 1-2 weeks and the practice is not equipped to assess/ treat pain conditions and behavioral issues related to substance use, the presenter recommends referral to a pain specialist. The same applies to the following cases [2]:

- if pain persists beyond a usual period of time

- In patients with a known history of addiction or an increased risk of overuse of analgesics.

- in the presence of an increased risk of severe postoperative pain

- for opoid tolerance

Screening for postoperative pain recommended

Risk factors for acute postoperative pain can be assessed by screening for the following criteria, according to Prof. Lawson, MD: Depression, anxiety, excessive subjective threat of pain, age <31, history of hyperalgesia and/or fibromyalgia, chronic use of opioids or anxiolytics, multiple procedures on the same day [2–4]. The speaker recommends guideline-based management based on appropriate guidelines and refers to those of the professional societies APS (American Pain Society) and ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists). Among other things, it formulates the following treatment recommendations: Use of two or more drugs with different mechanisms of action for analgesia in combination with non-pharmacological methods. Acetaminophen (acetaminophen) and/or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be used as a component of multimodal analgesia if there are no contraindications [2,5].

Therapy of acute and / or chronic pain at a glance

Acute pain: The speaker mentions tapentadol as a representative of the MOR-NRI substance class (“μ-opioid receptor agonists/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors”) and tramadol [2,6] as a representative of opioids (box) . For use as a non-opioid-based medication for acute pain, the following substances, for example, should be used, according to Prof. Lawson, MD: Nonsteorid anti-inflammatory agents (NSAID), α2-agonists, NMDA receptor antagonists, membrane stabilizers, muscle relaxants, topical agents.

Acute and chronic pain: For the combined treatment of acute and chronic pain, the speaker refers to a multimodal, multidisciplinary concept in which components from the following areas can be used: Non-pharmacological treatments, regional anesthesia, physical or occupational therapy methods, massage, cold/heat treatment, TENS, psychological pain therapy, psychiatric treatment of comorbid affective disorders/anxiety symptoms, methods of integrative and alternative medicine.

Chronic pain: Regarding the use of opioids, the speaker refers to current data from efficacy studies (study period of twelve weeks). Accordingly, opioids lead to a 30% increased reduction in pain intensity compared to placebo [2,7,8]. The long-term analgesic effects of opioids depend on dosage and possible development of tolerance [2,7,8]. In this regard, the risk of opioid dependence should also be considered.

The speaker referred to the 2016 “CDC Guideline for prescribing Opioids for chronic pain” [2,9] for the use of opioids in chronic pain management. This sets out recommendations in the following three areas:

- Start or continue use of opioids for chronic pain: weigh benefits and risks; combine with other therapies (pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic); discuss treatment goals with patient.

- Opioid treatment selection, dosing, duration of use, and follow-up and discontinuation: Lowest effective dosage; when initiating new opioid therapy, favor immediate-release over delayed-release agents; weigh benefits and risks, especially at dosages equivalent to ≥50 mg morphine/day (MME/day); avoid dosages ≥90 MME/day or titrate up cautiously; evaluate benefits and risks within 1-4 weeks of initiation of therapy; for longer-term use, evaluate every 3 months or more frequently; consider adjunctive therapy methods.

- Weigh and assess risks of adverse side effects: evaluate periodically before restart and during follow-up; consider naloxone if there is an increased risk of substance dependence disorder (e.g., history of addiction problems; opioid dosage ≥50 MME/day; concomitant use of benzodiazepines; urine test before restart and during follow-up).

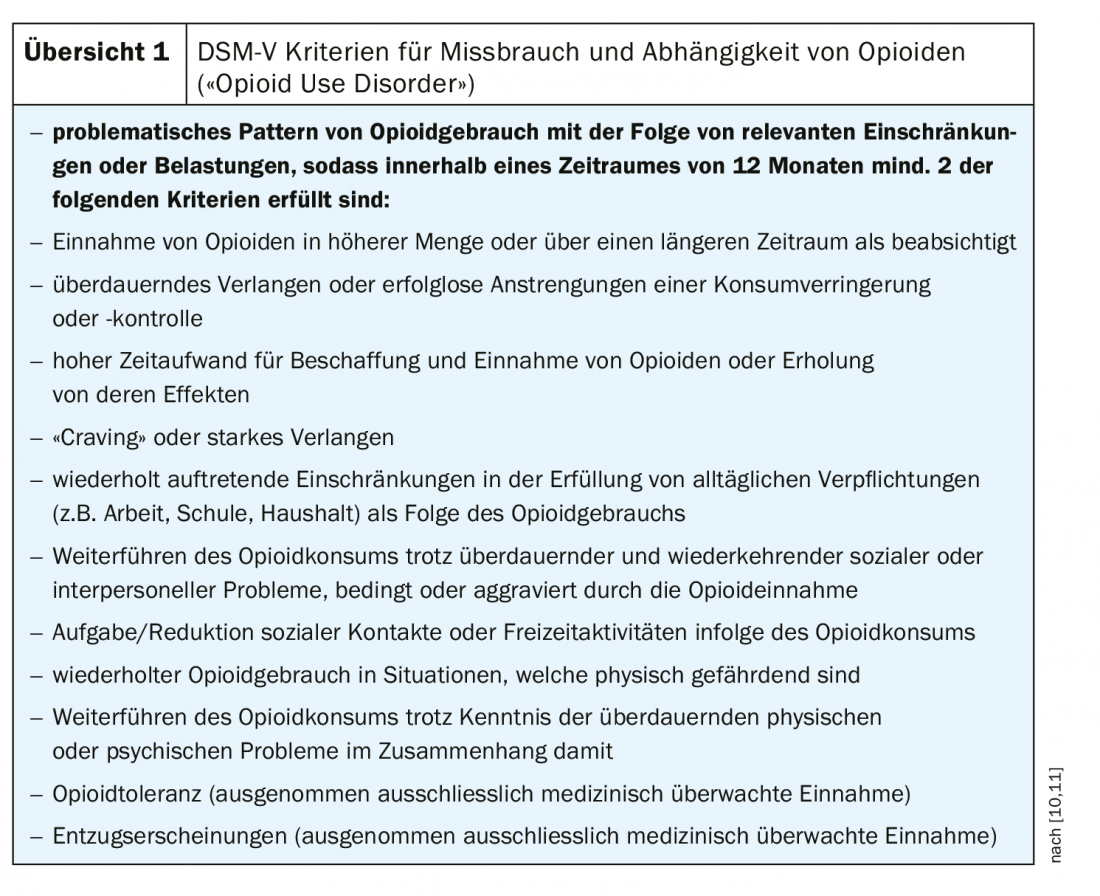

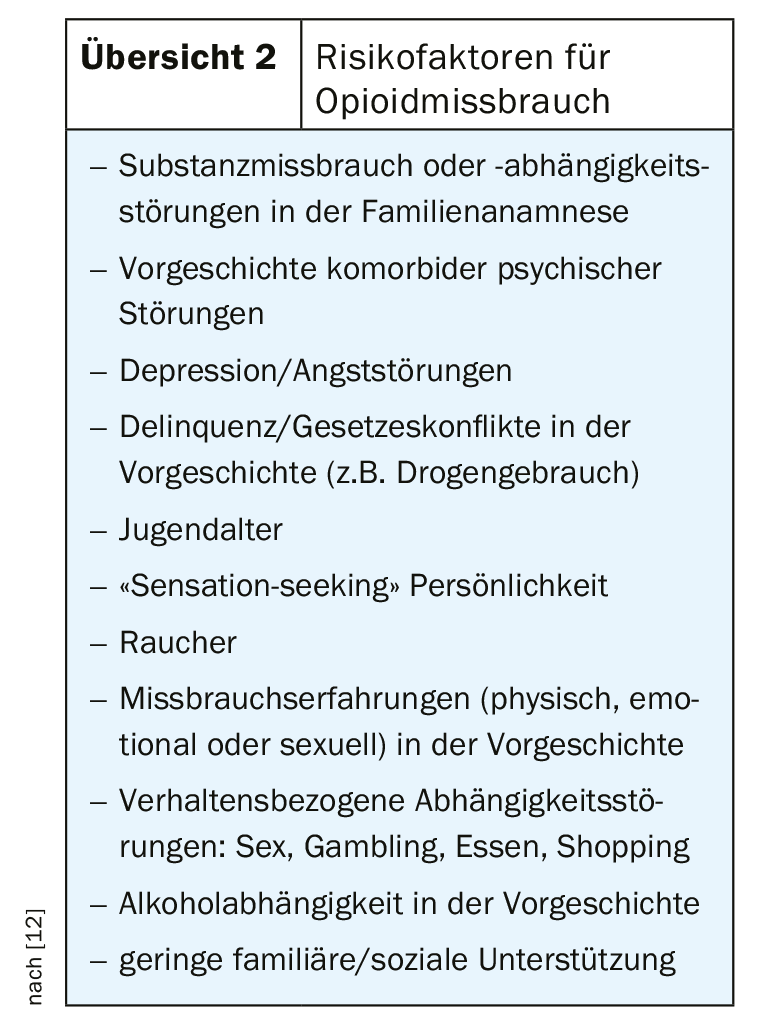

With regard to the management of the risk of opioid dependence (“opioid use disorder”), there are criteria in the DSM-V diagnostic manual [10], which relate, among other things, to dosage, duration of use and behavioral side effects (overview 1). Criteria for risk factors for developing opioid abuse can be seen in overview 2 .

Source: AAD Annual Meeting 2019, Washington (USA)

Literature:

- Beiteke U, Bigge S, Reichenberger C, Gralow I: Pain and pain therapy in dermatology. Journal of the German Dermatological Society 2015. CME article, available online (initial publication Sept. 26, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1111/ddg.10_12822, last accessed 03-06-2019.

- Lawson P: Slides: Universal Precautions/Risk Pain management for the dermatologist PERSPECTIVES FROM A PAIN SPECIALIST. Prentiss Lawson, Jr, MD. Assistant Professor. University of Alabama at Birmingham. Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine. AAD Annual Meeting, 2019, https://supportaad.org/scientificsessions/am2019/SessionDetails.aspx?id=12372

- Wardhan R, Chelly J: Recent advances in acute pain management: understanding the mechanisms of acute pain, the prescription of opioids, and the role of multimodal pain therapy. F1000Res. 2017 Nov 29; 6: 2065. doi:10.12688/f1000research.12286.1. eCollection 2017.

- Scott EL, et al: Beneficial Effects of Improvement in Depression, Pain Catastrophizing, and Anxiety on Pain Outcomes: A 12-Month Longitudinal Analysis. J Pain. 2016;17(2):215–22. 10.1016/j.jpain. 2015.

- Chou R, et al: Management of Postoperative Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016 Feb; 17(2): 131-157. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008. erratum in: J Pain. 2016 Apr:17(4): 508-510

- Vadivelu N, et al: Ketorolac, oxymorphone, tapentadol, and tramadol: A Comprehensive Review. Anesthsiol Clin. 2017 Jun;35(2):e1-e20.

- Sullivan MD, Howe CQ: Opioid therapy for chronic pain in the United States: promises and perils. Pain 2013; 154 (suppl 1): 94-100.

- Ballantyne J: Opioids for the Treatment of Chronic Pain: Mistakes Made, Lessons Learned, and Future Directions. Anesthesia and Analgesia 2017; 125: 1769-1778.

- CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain – United States, 2016. Recommendations and Reports, March 18, 2016; 65(1): 1-49.

- APA (American Psychiatric Association): Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. 2013. American Psychiatric Association Washington, DC.

- Covington EC, Bailey JA: In: Pain and Addictive Disorders: Challenge and Opportunity. H.T. Benzon et al. Practical Management of Pain: 5th ed. 2014. 669-682. Philadelphia: Mosby.

- Webster L: Risk Factors for Opioid Use Disorder and Overdose. Anesthesia and Analgesia 2017; 125: 1741-1748.

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2019; 29(2): 36-38