Accurate diagnostics including classification of the level of suffering must be performed. One should recognize “special cases” that entail specific somatic treatment. Educate the patient about possible causes and origins (“counseling”). To date, no drug with evidence-based proof of efficacy is on the market. Treatment of decompensated cases is carried out in an interdisciplinary team.

Tinnitus is a medical term for a ringing in the ears that patients perceive as a hissing, whistling, or buzzing sound. It is one of the most common symptoms in otolaryngology. The sound may occur in one or both ears. Most often, these are auditory sensations subjectively felt by the patient without external acoustic or electrical stimulation. Tinnitus is a symptom and not a disease. But tinnitus can significantly affect the quality of life, and accompanying anxiety disorders, depression, and concentration and sleep disorders often occur.

Nowadays, approximately 10% of people suffer from tinnitus and 17% of the population has experienced tinnitus lasting more than five minutes [1]. An increase is expected for the future, because the prevalence is rising among the younger generation. Best known risk factors are age, hearing impairment, noise exposure, stress, and mental illness [2].

Tinnitus can be classified according to various criteria (Tab. 1). Most important is the distinction between acute and chronic tinnitus. Acute tinnitus is defined as symptoms that have been present for up to three months, while chronic tinnitus is defined as symptoms that have been present for more than three months. Furthermore, the differentiation between subjective and objective ear noise follows; it is crucial that in the latter case a noise can also be perceived by the examiner.

Pathophysiology

Tinnitus is the result of a dysfunction of the auditory system, which can originate from different structures and levels. It is accompanied by changes in the central auditory system, but also in non-auditory areas. Tinnitus often develops in conjunction with damage to structures in the inner ear, which usually manifests clinically as sensorineural hearing loss. Chronic tinnitus becomes independent over time as an expression of a central disorder and becomes independent of the initial causative inner ear disorder, so that even radical interventions such as the severing of the auditory nerve or the removal of the cochlea do not lead to a silencing of the tinnitus. Therefore, the current focus of research is on central mechanisms of development and processing. However, perception is only possible through activation in the auditory system and functional coupling to frontal and parietal areas. Kleinjung et al. report that at least 14 brain regions are involved in tinnitus [3].

In analogy to the chronic pain syndrome, tinnitus can be seen as a “phantom pain of the ear”. Chronic pain and tinnitus are both associated with specific functional changes within the central nervous system, ultimately as a consequence of neural plasticity of the central auditory pathway and central pain-processing structures.

Causes

Acute tinnitus often presents with a disease correlate such as acute inflammation (otitis media acuta, flu otitis), tubal middle ear catarrh, tympanic membrane perforation, or various traumas such as noise, blast, baro, or traumatic brain injury. Typically, acute tinnitus also occurs in the context of a hearing loss. However, acute tinnitus can also occur as a sole symptom without an identifiable cause, so-called idiopathic.

Chronic tinnitus is associated with hearing loss in 95% of cases. Sensorineural hearing loss such as noise-induced hearing loss, Meniere’s disease, hereditary hearing loss or, in rare cases, vestibular schwannoma should be mentioned. In the case of middle ear hearing loss, otosclerosis is most commonly thought of (Tab. 2) . Controversial causes of tinnitus are cervical spine problems such as cervical distortion trauma or muscular tension. A connection with functional disturbances of the jaw movement apparatus in the sense of myoarthropathy with teeth grinding is also discussed, however without convincing pathophysiological explanation.

In objective tinnitus, the examiner can perceive the sounds himself, e.g., by means of a stethoscope. This can be caused, for example, by vascular diseases such as an aneurysm of the internal carotid artery, arteriosclerotic vascular stenoses, arteriovenous vascular malformations or a glomus tumor. The tinnitus in the latter is then typically pulse synchronous.

A rarity is tinnitus of muscular origin. It is generated by spontaneous muscle contractions of the stapedius muscle, tensor tympani muscle, or tensor veli palatini muscle. The tinnitus is described as clicking, rhythmic, or volley-like. When the tensor veli palatini muscle is involved, partially synchronous movements of the soft palate are found. A continuous tympanogram can also objectify this tinnitus. Therapy for high levels of distress consists of severing the tendons of the stapedius and tensor tympani muscles in the middle ear or Botox injection.

Diagnostics

In the family practice, it is important to determine whether the tinnitus is acute or already chronic. Furthermore, the anamnesis includes questioning about risk factors (noise, stress, comorbidities), circumstances of occurrence and character of the ringing in the ears.

Any additional otologic symptoms such as ear pain, hearing loss, dizziness, or otorrhea, as well as an otoscopy to evaluate the eardrums, will guide further procedures. A tuning fork examination provides additional evidence of a hearing disorder.

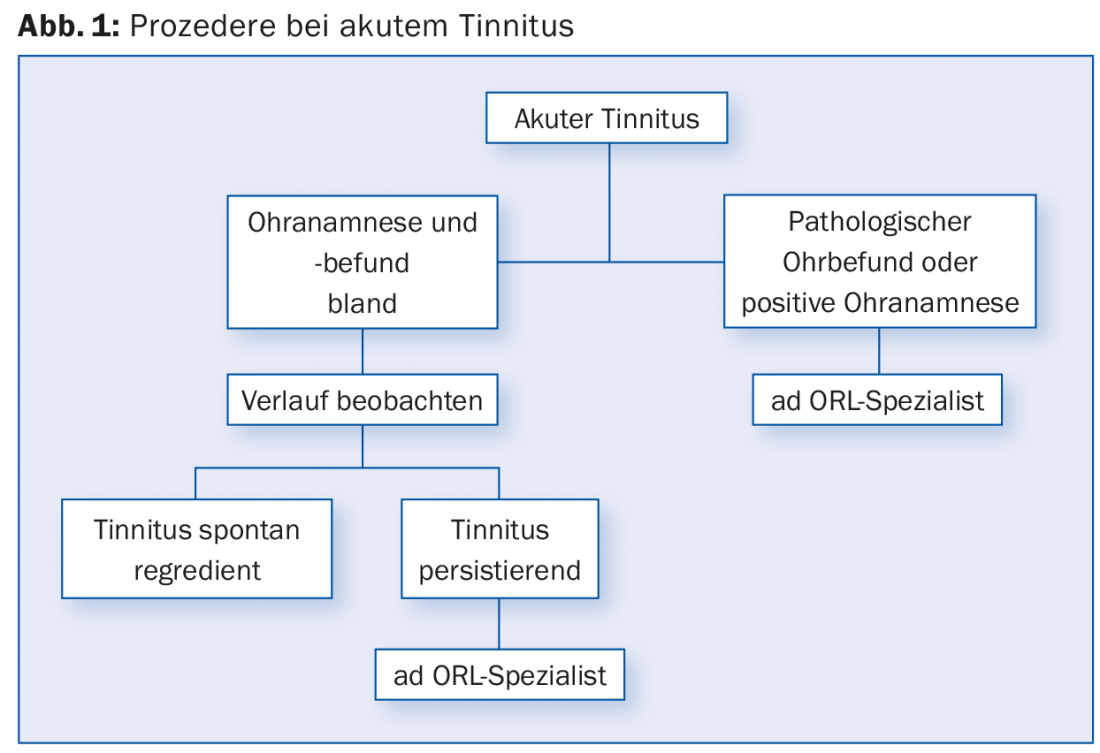

In cases of acute tinnitus without ear symptoms, especially without hearing loss, it is possible to wait because it is often self-limiting and there is no evidence-based treatment option. In case of additional acute hearing loss in the sense of a hearing loss, in case of further ear symptoms or in case of pathological otoscopic findings, a prompt clarification by the ORL specialist is recommended.

In the case of chronic tinnitus, the same procedure is followed with regard to anamnesis and diagnostic findings. In the case of unilateral chronic tinnitus without anamnestic cause or pathological ear findings, an MRI should be performed to exclude a retrocochlear cause (e.g., vestibular schwannoma), especially in the presence of unilateral sensorineural hearing loss. In the case of chronic tinnitus, however, there is the additional question of the suffering pressure and the coping strategy, i.e. whether the tinnitus is still compensated or not. Various tinnitus questionnaires (e.g., Tinnitus Handicap Inventory [THI]) exist for estimating the actual burden of tinnitus [4]. In the case of chronic tinnitus with corresponding suffering pressure, a consultation with an ORL specialist is recommended.

In the rather rare situation of pulsatile tinnitus, auscultation of the large neck vessels and the periauricular region is also performed. Usually, further workup includes MRI with MR angio and duplex ultrasonography of the neck vessels.

Therapy

In acute tinnitus, if a causative pathology is present, appropriate targeted therapy is initiated, e.g., antibiotic treatment in otitis media acuta or steroid therapy in acute hearing loss or acute noise trauma. Usually the tinnitus disappears when the disease correlate heals. In the case of acute tinnitus without further symptoms or suffering, the course can be waited for (Fig. 1).

One of the principles of tinnitus therapy for chronic tinnitus is to listen carefully to the complaints and take them seriously. Sufficient time should be allowed for appropriate consultation during office hours. After the diagnosis has been made, the patient is informed about possible triggering factors and pathophysiological correlations for the development of the disease. Since many patients are also concerned about whether a serious disease (e.g., carcinophobia) underlies the complaints, this problem should also be addressed accordingly. Sensitization must be avoided in the process.

In the past, a wide variety of drugs were tested for their effectiveness against tinnitus. To date, none has been shown to have evidence-based efficacy. A meta-analysis of the Cochrane database also failed to demonstrate efficacy for herbal preparations such as ginkgo [5]. In summary, there are currently no proven effective and officially approved medications for chronic tinnitus on the market [6].

Other methods, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation or laser treatments, have also been postulated but showed no long-term effect [7,8]. In contrast, a study by Cima et al. [9] that a standardized stepwise approach with elements of cognitive behavioral therapy and tinnitus retraining therapy showed an improvement in the quality of life of tinnitus patients. From an ENT point of view, any hearing impairment can be treated with communication-oriented hearing aids. Alternatively, in appropriate cases, surgical hearing rehabilitation in terms of an implantable hearing aid should be considered.

Since cochlear implantation, a positive side effect has been an improvement in tinnitus in approximately 50% of cases [10,11]. This option is considered in cases of profound deafness or extreme distress, as the remaining hearing may be lost during surgery. However, implantation is cost-intensive and is currently not covered by health insurance in the case of tinnitus alone.

In patients with psychiatric comorbidity, the underlying disease should be treated. An underlying depressed mood can amplify the perception of a ringing in the ears, generating a negative spiral. Therefore, appropriate therapy (medication, psychotherapy) is recommended to favorably influence depressive symptomatology and thus tinnitus.

However, the most important thing is not therapy, but prevention. So-called “hearing hygiene” is recommended, with avoidance of acoustic stimulus overload, consistent noise protection at work and during leisure time, stress reduction, learning relaxation techniques, and elimination of risk factors for vascular diseases (diet, nicotine).

Literature:

- Henry JA, et al: General review of tinnitus: prevalence, mechanisms, effects, and management. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2005; 48: 1204-1235.

- Schaaf H, et al: Chronic stress as an influencing factor in tinnitus patients. HNO 2014; 62: 108-114.

- Kleinjung T, et al: Paths to silence. Brain and Mind 2011; 1-2: 38-42.

- Newman CW, et al: Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996; 122(2): 143-148.

- Hilton MP, et al: Ginkgo biloba for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 28: 3.

- Baguley DM, et al: Tinnitus. Lancet 2013; 382: 1600-1607.

- Hoekstra CE, et al: Bilateral low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the auditory cortex in tinnitus patients is not effective: a randomised controlled trial. Audiol Neurootol 2013; 18: 362-373.

- Ngao CF, et al: The effectiveness of transmeatal low-power laser stimulation in treating tinnitus. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2014; 271: 975-980.

- Cima RF, et al: Specialised treatment based on cognitive behaviour therapy versus usual care for tinnitus: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012; 379: 1951-1959.

- Arts RA, et al: Review: cochlear implants as a treatment of tinnitus in single-sided deafness. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012; 20: 398-403.

- Olze H, et al: Cochlear implantation has a positive influence on quality of life, tinnitus, and psychological comorbidity. Laryngoscope 2011; 121: 2220-2227.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(7): 26-30