The treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has made great progress over the past 20 years. This relates both to the range of drugs available and to developments in terms of rapid onset of action and response rates. JAK inhibitors have emerged as an alternative to biologics in this regard, with some advantages.

The treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has made great progress over the past 20 years. This relates both to the range of drugs available and to developments in terms of rapid onset of action and response rates. JAK inhibitors have emerged as an alternative to biologics in this regard, with some advantages.

Considering the not easy handling (necessity of cooling, parenteral administration), biologics are not the optimal form of therapy for all patients, especially since only a minority achieves continuous clinical remission under them. Pain, functional limitations, fatigue and depression, on the other hand, impose a high disease burden on those affected. JAK inhibitors are positioned in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis after treatment failure on csDMARDs or biologics.

The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) has recommended that patients with poor response to csDMARD (e.g., methotrexate, MTX) and unfavorable prognosis be treated with either bDMARD or a JAK inhibitor [1]. If this does not result in a therapeutic response, a change of substance or class (from bDMARD to JAKi or vice versa) should be tried. For both biologic and targeted synthetic DMARDs (b/tsDMARDs), combination therapy with a csDMARD is recommended. If such is ruled out (for example, due to contraindications), EULAR advises that IL-6 and JAK inhibitors be preferred over other bDMARDs.

In Switzerland, three JAK inhibitors are currently available for the treatment of RA: Tofacitinib, Baricitinib and Upadacitinib. In addition, filgotinib has been approved in Germany since 2020 and peficitinib has been available on the Japanese market since 2019, but is not yet allowed in the U.S. or Europe. When choosing the appropriate JAK inhibitor, the question of compound-specific differences in efficacy and safety profile is often of greatest interest to practitioners.

Tofacitinib

The selectivity of JAK inhibitors, i.e. the inhibition of individual isoforms at a certain intracellular concentration, is the main focus of investigations. The optimal ratio of effectiveness and side effects is thus sought, as in the case of anemia, for example. For tofacitinib, already approved in Switzerland since 2013, a post-hoc analysis regarding seropositive and seronegative patients has shown a comparable response in both groups [2]. DAS28 remission rates were slightly lower than in CCP patients. In the analysis, data from five phase III studies were pooled and subgroups were defined based on serology: RF+CCP+, RF+CCP-, RF-CCP+, and RF-CCP-. As a result, patients with RF+CCP+ had a higher likelihood of achieving an ACR-20, -50, or -70 response than RF-CCP patients. This result was demonstrated for ACR-20 and -50 response for both tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily. In contrast, the ACR-70 response was better only at the higher dose.

Another study looked at the risk of cardiovascular events with tofacitinib. Analysis of a phase IV study comparing tofacitinib with TNF blockers (adalimumab, etanercept) in patients older than 50 years with at least one additional risk factor for cardiovascular events showed that the risk for thromboembolic events associated with tofacitinib must be considered increased.

The risk of pulmonary embolism was also significantly increased with tofacitinib at the 10-mg dose and was similarly higher with 5 mg twice daily than in previous studies. Also, all-cause mortality was higher under 10 mg twice daily than under 5 mg twice daily. Therefore, in 2019, the EMA issued a recommendation that tofacitinib should not be used in patients at increased risk of thromboembolism. RA patients over 65 years of age should be treated with tofacitinib only if there is no therapeutic alternative.

Upadacitinib

A comparison was made for upadacitinib vs adalimumab vs placebo in MTX-IR patients with active RA in the SELECT-COMPARE trial [3]. In this study, there was an option to switch from upadacitinib to adalimumab at week 12 as well as vice versa (at weeks 14, 18, 22, and 26) if there was less than 20% improvement in painful and swollen joints (co-primary endpoints ACR20 and DAS28-CRP <2.6).

In the study of 1629 patients with active RA despite MTX, upadacitinib (approved in Switzerland since spring 2020) was shown to be statistically significantly more effective than adalimumab: 71% of patients achieved an ACR20 response with upadacitinib, compared with only 63% with adalimumab and 36% with placebo. 29% of patients achieved remission according to DAS28-CRP, compared with only 18% on adalimumab and 6% on placebo. In terms of adverse events, herper zoster and CK elevations were more common with upadacitinib, and venous thromboembolism (VTE) occurred in 3 patients with adalimumab vs. 2 patients with upadacitinib. Looking at the non-responders, it was seen that when switching from upadacitinib to adalimumab, 13% achieved remission, while conversely, switching from adalimumab to upadacitinib achieved the desired outcome in 26%.

In the SELECT-MONOTHERAPY trial, 648 patients with active RA despite MTX were randomized to either continuation of MTX therapy or upadacitinib 15 mg or 30 mg as monotherapy [4]. Again, a significantly better response was seen with upadacitinib: after 14 weeks, an ACR20 response was achieved in 68% of patients on upadacitinib 15 mg and 71% on upadacitinib 30 mg, compared with only 41% of patients who continued MTX therapy.

Baricitinib

Baricitinib has been approved in Switzerland since 2017 at a dose of 4 mg (2 mg in elderly patients or in renal insufficiency). In clinical trials, the drug once daily at doses of 2 mg and 4 mg has previously shown significant clinical efficacy with acceptable safety [5,6]. The most commonly reported serious adverse events (SUEs) during the placebo-controlled period were infections.

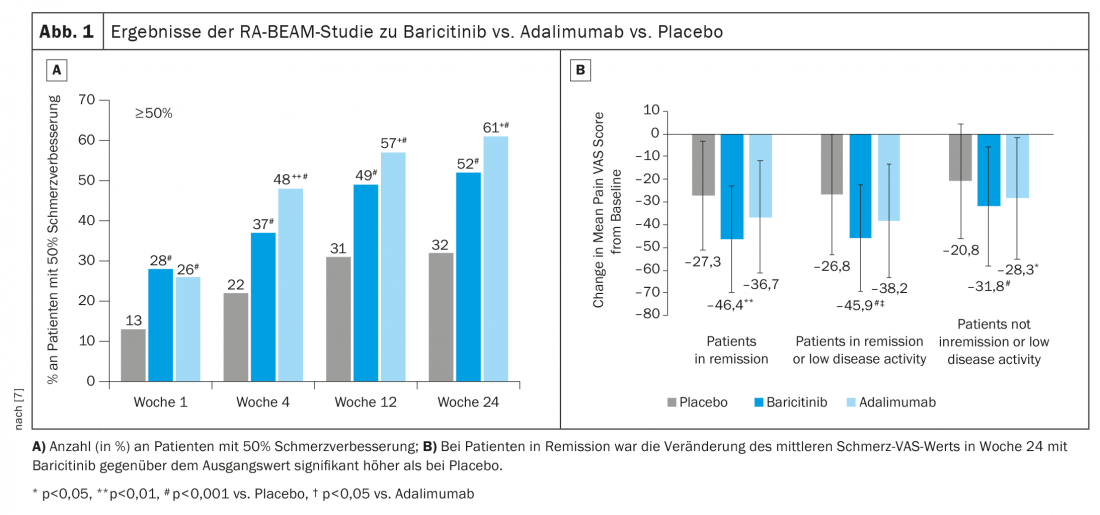

In the RA-BEAM trial, baricitinib 4 mg + MTX was compared with adalimumab + MTX and placebo + MTX [7]. Here, the 50% improvement in pain has been found to be better with baricitinib (Fig. 1A). Nevertheless, looking more closely at only those patients who are in remission or low disease activity, there is a significantly meaningful effect on pain with baricitinib (Fig. 1B). The positive effect could still be observed after a switch from adalimumab to baricitinib after week 16.

Regarding vaccination response under baricitinib, PCV13 and tetanus toxoid (TT) have been tested. 106 patients from the RA-BEYOND trial of 2 mg or 4 mg baricitinib (with and without MTX) were vaccinated with PCV13 and against tetanus. Overall, 68% of patients showed adequate vaccine response to pneumococcal disease, and 43% achieved an increase in vaccine titers of more than 4-fold to tetanus. An increase of more than 2-fold after PCV13 was achieved by 74% of patients [8].

New study on the long-term effect

The long-term safety of baricitinib in 3770 pa-tients (10 127 patient-years of exposure, PYE) during the clinical development program has been reported previously [9]. Because baricitinib, like other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), is used chronically in patients with RA, it is important to continuously monitor and evaluate its evolving long-term safety profile. These long-term data are most relevant to assess the incidence and risk of unusual adverse events of special interest (AESI), including malignancies and serious adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). Since the previous analysis, the long-term-extension (LTE) study has been completed and Prof. Peter C. Taylor, Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences, University of Oxford, and colleagues have presented results in an update of data from up to 9.3 years of treatment [10].

Their review analyzed pooled data from patients ≥18years of age with moderate-to-severe active RA from nine randomized clinical trials (five phase III, three phase II, one phase Ib) and one completed LTE. Exclusion criteria included current or recent (<30 days before study entry), clinically serious infections requiring antimicrobial treatment, and selected laboratory abnormalities (eg, liver/kidney function tests, selected hematology and infectious disease markers). Baricitinib doses ranged from 1 mg to 15 mg daily, with 2-mg and 4-mg daily doses used in the phase III and LTE trials, respectively.

Patients who completed Phase III and Phase II trials were eligible for LTE. Patients randomized to baricitinib 2 mg in the original study who were not saved continued therapy at the same dose in the LTE; all other patients received baricitinib 4 mg at the LTE entry. Patients who received 4 mg for at least 15 months without rescue and achieved sustained low disease activity (Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score ≤10) or remission (CDAI score ≤2.8) were blindly rerandomized to 4 mg or down-regulated to 2 mg.

RA patients at increased risk of infection

The incidence of death, serious adverse events (including infections), MACE, and malignancy for baricitinib was similar to those observed for other therapeutic trials of JAK inhibitors and biologic DMARDs, the authors noted. Few patients (exposure-adjusted incidence rate, EAIR, 4.7) discontinued therapy because of adverse events. In the baricitinib 2 mg and 4 mg subgroups, the incidence of AESI was similar between the two dosing groups.

The risk of mortality in patients treated with baricitinib was not increased compared with the general population after controlling for age and sex, with a Standardized Mortality Ratio (SMR) of <1 for baricitinib. The causes of death for patients treated with baricitinib are consistent with the percentages of overall deaths in the U.S. general population and those reported in clinical trials of other RA therapies.

Due to disease and therapeutic interventions, patients with RA have an increased risk of infection. The overall incidence of serious infections has remained stable over time. EAIR of severe infections in the baricitinib 2 mg group could be numerically lower than under 4 mg, which is related to lower disease activity and lower use of corticosteroids and MTX at baseline. Infections that resulted in death were rare in this patient population. The incidence of herpes zoster remained stable and similar to that of other JAK inhibitors including tofacitinib [11] and upadacitinib [12].

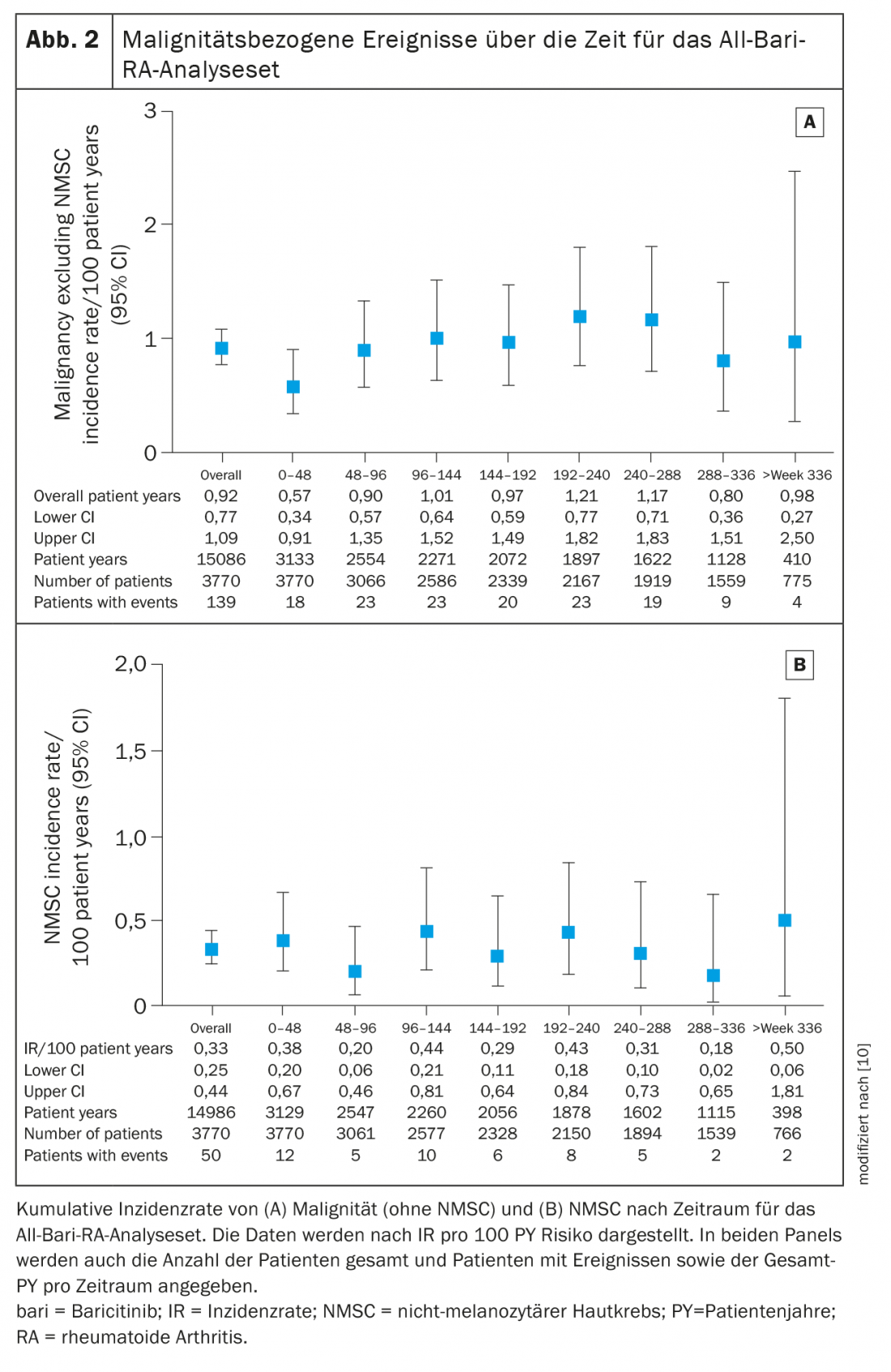

Since their previous evaluation, there have been an additional 54 cases of malignancy (excluding NMSC) with a similar IR (0.9 in the current analysis vs. 0.8), write Taylor et al. [10]. Patients with RA are predisposed to an increased risk of malignancy, particularly lymphoma, lung cancer, and NMSC (non-melanocytic skin cancer), he said. The incidence of lymphoma remained unchanged at 0.06 from previous reports of baricitinib and similar to other RA therapies, including an IR of 0.1 for adalimumab and 0.096 for patients using TNF inhibitors.

Risks for malignancies remain unclear

The effects of JAK inhibitors on malignancy risk remain unclear and require further research. Data from a recent systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that there was no increased risk of malignancy in patients who combined a JAK inhibitor with MTX compared with pa-tients treated with MTX alone [13]. Prof. Taylor and colleagues note that 79% of the patients included in their analysis used concomitant MTX. In addition, no increased risk of malignancy has been reported from observational studies between other JAK inhibitors (tofacitinib) compared with conventional synthetic DMARDs or biologic DMARDs such as TNFi [14].

The IR for malignancy (excluding NMSC) during the first 48 weeks in your evaluation was 0.6 (95% CI 0.34-0.91) and remained stable thereafter at approximately 1.0 (overall IR 0.9, 95% CI 0.77-1.09) (Fig. 2A). The most commonly reported types of malignancies were respiratory and mediastinal (n=26, EAIR=0.17), breast (n=23, EAIR=0.15), and gastrointestinal (n=19, EAIR=0.13). The IR for NMSC was 0.3 (95% CI 0.25-0.44) and did not increase over time (Fig. 2B) . The IR for lymphoma was 0.06 (95% CI 0.03-0.11), with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma remaining the most common subtype.

Patients with RA have an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) (IR 0.3-0.8/100 patient-years) compared with the general population [15,16]. In this analysis, the IR of DVT/PE in patients treated with baricitinib was consistent with previously reported data and comparable to other JAK inhibitors [9]. In the subgroup of patients receiving baricitinib 2 mg or 4 mg, EAIRs were similar between dose groups and comparable to those previously reported. While recent meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of JAK inhibitors (including tofacitinib, baricitinib, and upadacitinib) in patients with RA have not shown an increased risk of venous thromboembolic events during placebo-controlled periods, longer-term data are needed to fully characterize the risk of these events, according to the authors. The incidence of MACE in the current study (0.5) also remained low and stable compared with previous reports. The EAIR of MACE was similar between baricitinib 2 mg (0.42) and 4 mg (0.54). Of the patients, 55% had at least one of five cardiovascular risk factors at baseline used in the analysis (current smoker, hypertension, diabetes, history of atherosclerotic disorder, or HDL cholesterol <40 mg/dl); as expected, the IR for MACE was higher in this risk subpopulation (0.70).

The EAIR for diverticulitis in the current study (0.15) is consistent with published data in patients with RA [17]. Important risk factors for diverticulitis in the general population include age, obesity, diet, smoking, and medication use, especially opioids, corticosteroids, and NSAIDs. Diverticulitis in the long-term study occurred in patients with risk factors. The IR for gastrointestinal perforations (0.06) remains low in the context of reports of tofacitinib, tocilizumab, and other biologic DMARDs in real-world data and in relation to upadacitinib (0.08/100 patient-years) [18].

Take-Home Messages

- As disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, JAK inhibitors are used chronically in patients with RA. It is important to continuously monitor and evaluate the evolving long-term safety profile.

- The safety profile of JAK inhibitors in clinical trials includes an increased risk of herpes zoster and associations with increased cardiovascular events, venous thromboembolic events (VTE), and malignancies.

- In a recent long-term study of baricitinib, the agent was stable with respect to safety-related events including deaths, malignancies, MACE, and DVT/PE over a period of up to 9.3 years and was generally similar between the 2 mg and 4 mg groups.

- The results suggest that baricitinib has a consistent safety profile and is in line with other JAK inhibitors and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

- Continued follow-up and further research, including long-term population-based studies, are needed to fully understand the risk of endpoints, including malignancies, MACE, and VTE, and the comparative real-world risk of baricitinib and therapies in RA.

Literature:

- Smolen JS, et al: EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79: 685-699; doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216655.

- Bird P, Hall S, Nask P, et al: RMD open 2019; 5: e000742; doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000742.

- Fleischmann R, Pangan AL, Song ICH et al: Arthritis Rheumatol 2019; 71(11): 1788-1800.

- Smolen JS, Pangan AL, Emery P, et al: Lancet 2019; 393: 2303-2311.

- Taylor PC, Keystone EC, van der Heijde D, et al: Baricitinib versus placebo or adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 652-662; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1608345

- Genovese MC, Kremer J, Zamani O, et al: Baricitinib in patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 1243-1252; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507247

- Fautrel B, Kirkham B, Pope JE, et al: J Clin Med 2019; 8: 1394-1408.

- Winthrop K, Bingham CO, Komocsar WJ, et al: Arthritis Res Ther 2019; 21: 102-112.

- Genovese MC, Smolen JS, Takeuchi T, et al: Safety profile of baricitinib for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis over a median of 3 years of treatment: an updated integrated safety analysis. Lancet Rheumatol 2020; 2: e347-e357; doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30032-1.

- Taylor PC, Takeuchi T, Burmester GR, et al: Safety of baricitinib for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis over a median of 4.6 and up to 9.3 years of treatment: final results from long-term extension study and integrated database. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2021 (online first); doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221276.

- Winthrop KL, Curtis JR, Lindsey S, et al: Herpes zoster and tofacitinib: clinical outcomes and the risk of concomitant therapy. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69: 1960-1968; doi: 10.1002/art.40189.

- van Vollenhoven R, Takeuchi T, Pangan AL: A phase 3, randomized, controlled trial comparing upadacitinib monotherapy to MTX monotherapy in MTX-naïve patients with active rheumatoid arthritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018; 70.

- Solipuram V, Mohan A, Patel R, et al: Effect of Janus kinase inhibitors and methotrexate combination on malignancy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Auto Immune Highlights 2021; 12(8); doi: 10.1186/s13317-021-00153-5.

- Xie W, Yang X, Huang H, et al: Risk of malignancy with non-TNFi biologic or tofacitinib therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2020; 50: 930-937; doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.08.007.

- Kim SC, Schneeweiss S, Liu J, et al: Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2013; 65: NA-7; doi: 10.1002/acr.22039.

- Ogdie A, Kay McGill N, Shin DB, et al: Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a general population-based cohort study. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 3608-3614; doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx145.

- Bharucha AE, Parthasarathy G, Ditah I, et al: Temporal trends in the incidence and natural history of diverticulitis: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110: 1589-1596; doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.302.

- Cohen SB, van Vollenhoven RF, Winthrop KL: Correction: safety profile of upadacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis: integrated analysis from the SELECT phase III clinical programme. Ann Rheum Dis 2021; 80: 304-311; doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218510.

InFo PAIN & GERIATURE 2021; 3(2): 6-9.