Vascular dementia was the subject of a presentation at the Prevention Summit at the University Hospital Zurich. PD Dr. med. Urs Schwarz, University Hospital Zurich, gave an overview of this complex and inhomogeneous condition. A possible link between dementia and blood pressure was also discussed. Studies have not yet reached a conclusive conclusion in this regard, but it seems very unlikely at this time that lowering blood pressure can prevent dementia.

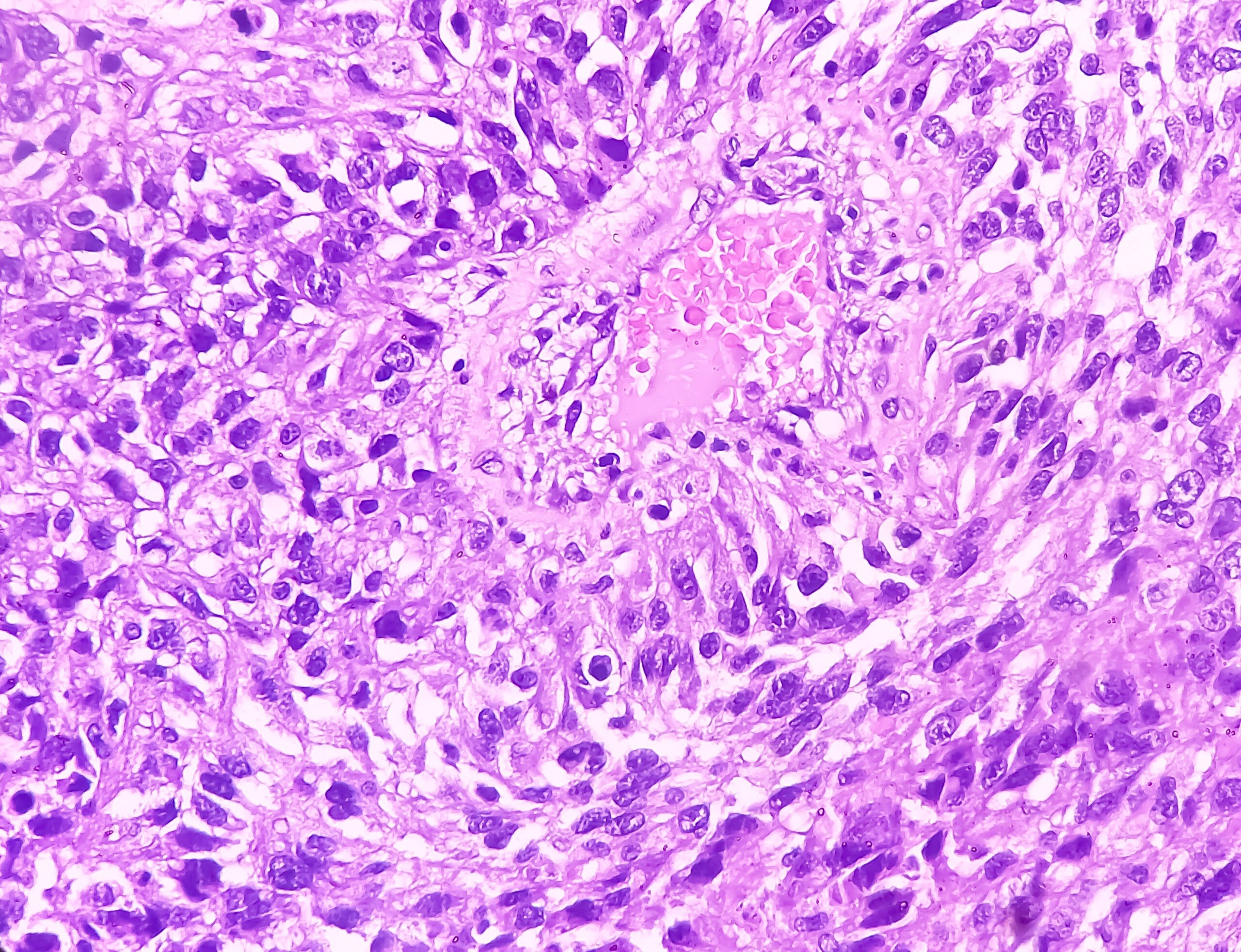

(ag) Urs Schwarz, MD, University Hospital Zurich, spoke at the Prevention Summit on the topic of hypertension and dementia. “Taking a history is key,” he said. “A sudden onset is typical. Vascular dementia is often detected after a stroke. The thing to keep in mind here is that the stroke itself does not lead to vascular dementia; it usually simply becomes apparent at that point.” Given the complex etiology, “vascular dementia” is merely an umbrella term and not a uniformly describable clinical picture. “An inhomogeneous condition that we don’t really understand pathophysiologically and neuropathologically,” Dr. Schwarz called vascular dementia. “The prevalence is unclear, the spectrum is wide.”

Basically, vascular cognitive disorders can be divided into different categories:

- VCI (“vascular cognitive impairment”): Equivalent to the term CI-ND (“cognitive impairment no dementia”) and vascular MCI (“vascular mild cognitive impairment”).

- VaD (“vascular dementia”): Dementia is defined as a deficit in executive function leading to loss of functional daily living skills (“activities of daily living”, ADL).

- Mixed Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) and cardiovascular disease: Pre-existing AD worsened by stroke.

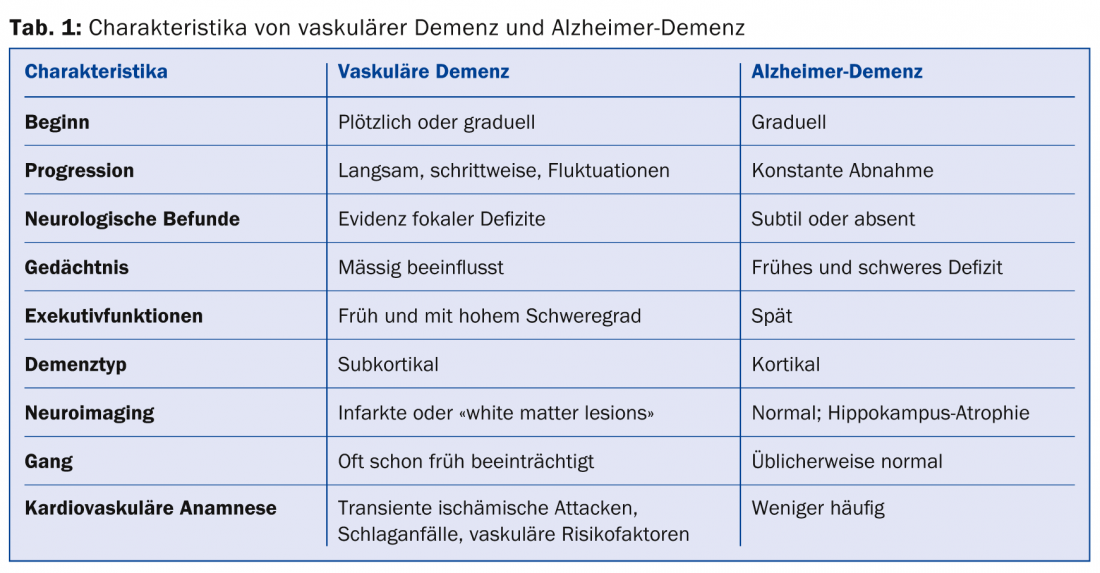

The progression of vascular dementia is gradual and at varying rates (even halting), this in contrast to AD. Nevertheless, the symptoms are similar to other forms of dementia. Decreases in memory, thinking speed, concentration, and communication (slowing down and a dull stare ahead) may be associated with depression and anxiety, as well as delirious states. In addition, behavior may change, incontinence may occur, and some restlessness may be observed. In the case of additional gait disturbance, one speaks of typical “lower-body” parkinsonism. Table 1 compares characteristics of vascular dementia with those of AD.

Epidemiology not definable at all?

The epidemiology of vascular dementia is controversial because of the great difficulty in diagnosis. Incidence varies widely by country and health care system (in contrast to the incidence of AD). According to clinical data, the prevalence is approximately 0.3% (AD 0.6%) in 65- to 69-year-olds and 5.2% (AD 22.2%) in those over 90 years of age. Vascular dementia accounts for about 15.8% of all dementias, and AD accounts for 53.7%. “The real prevalence numbers are almost certainly much higher-probably not quite as high as those for AD, but keep in mind that prevalence data for vascular dementia vary by paper by as much as 70% (in Asian countries),” the speaker cautioned.

Hypertension and dementia

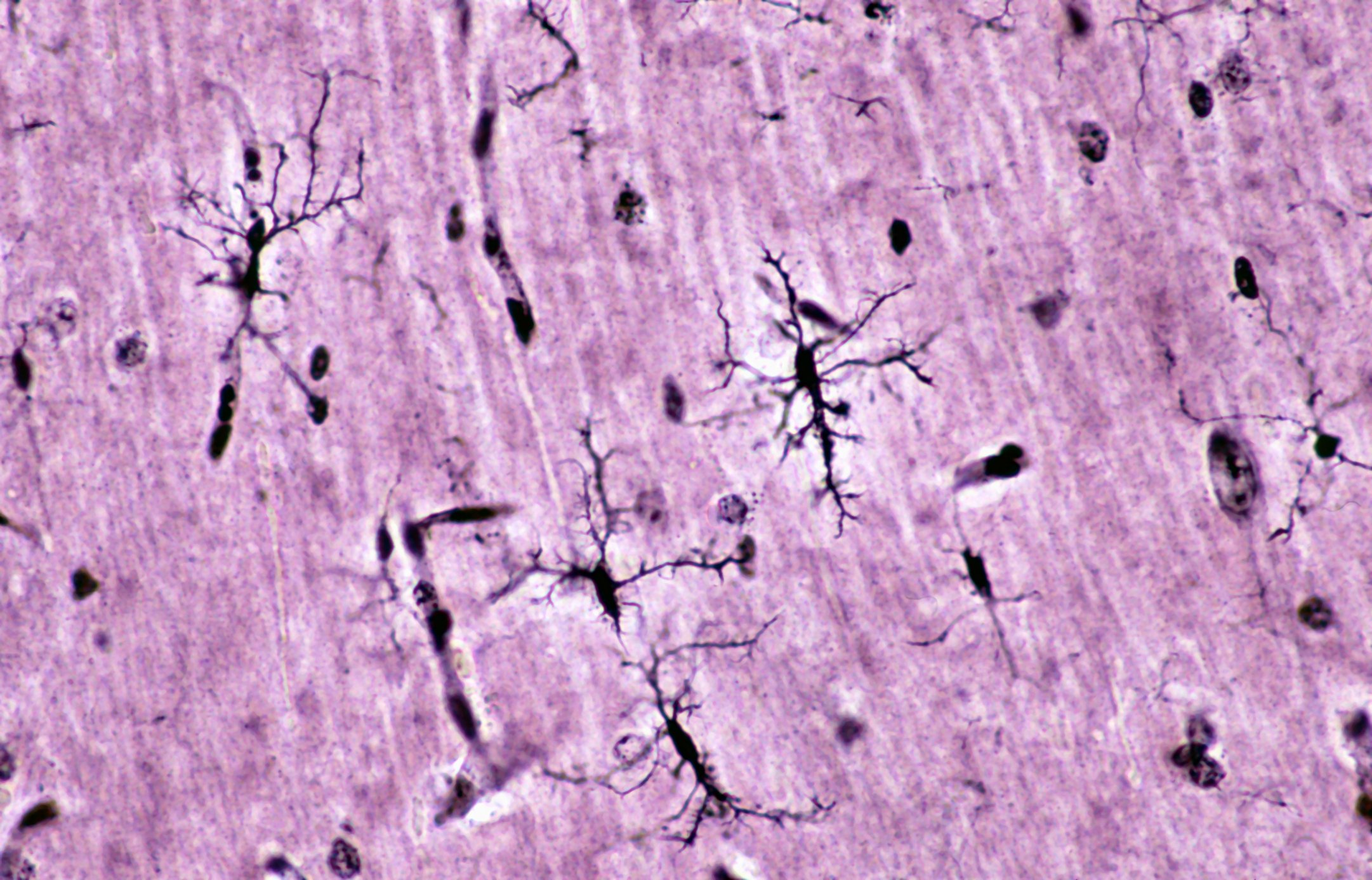

How is hypertension related to dementia in general, or what happens in the brain when hypertensive patients are given blood pressure lowering? Both gray and white matter are discussed as potentially influenceable factors. The alteration of both substances is in turn associated with the deterioration of cognitive functions [1], but this is also highly controversial, at least for the “white matter lesions”. According to the speaker, many elderly people show such lesions (they are also partly dependent on blood pressure), but this is far from being a sure or even sufficient indication of vascular dementia. There is association, but not causality.

Study situation unclear

A 2012 study [2] hypothesized that gray matter volume reduction in the brain may be associated with hypertension. Can the process thus be influenced by a new antihypertensive therapy? 41 patients (without dementia but with hypertension) were studied over the course of one year of treatment. The results were disappointing – despite successful blood pressure reduction, volume reduction continued. A recently published review of 155 papers that examined the potential benefits and harms of antihypertensive therapy in (already) demented patients came to the sobering conclusion that there is strong evidence in neither domain [3]. Neither clear advantages nor disadvantages of antihypertensive therapy in the demented have been shown.

“If one surveys the literature, one comes to a negative conclusion. The longitudinal studies that investigated the benefit of antihypertensive treatment on cognitive parameters are not uniform: three tend to contain positive results (SYST-EUR, PROGRESS, HOPE), four tend to contain negative results (MRC, SHEP, SCOPE, HYVET-COG). In conclusion, the role of antihypertensive therapy in stopping or even preventing cognitive impairment seems to be rather insignificant or at least cannot be assessed conclusively so far. With the current state of knowledge, it can be said: Of course, hypertension must be treated, but this does not protect against dementia,” says the expert.

What do the guidelines say?

The 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension state that although white matter lesions are known to be associated with increased risk of cognitive impairment and dementia, there is little information that antihypertensive therapy can influence this development.

Source: “Hypertension and Dementia,” presentation at Prevention Summit, September 11, 2014, Zurich.

Literature:

- Longstreth WT, et al: Clinical correlates of white matter findings on cranial magnetic resonance imaging of 3301 elderly people. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke 1996 Aug; 27(8): 1274-1282.

- Jennings JR, et al: Regional gray matter shrinks in hypertensive individuals despite successful lowering of blood pressure. J Hum Hypertens 2012 May; 26(5): 295-305.

- Van der Wardt V, et al: Antihypertensive Treatment in People With Dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014 Sep; 15(9): 620-629.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(10): 35-36