Americans further downgrade the definition of hypertension, from formerly ≥140/90 mmHg to newly ≥130/80 mmHg. The new guideline was hotly debated at the AHA Congress.

The new guidelines come from the two major US cardiology societies, the AHA and ACC [1]. As before, the limit of <120/<80 mmHg is defined as normal. However, if the systolic values – with the same diastolic values – are above this, i.e. 120-129, the new guidelines already speak of “elevated” blood pressure, whereas the old US guidelines spoke of “prehypertension” if the diastolic value was also 80 mmHg or more. From values of 130 (syst.) or 80 mmHg (diast.), grade 1 hypertension is now present (formerly “prehypertension”) and at the “usual” limit of 140/90 mmHg, grade 2 hypertension is now already present. Individuals whose systolic and diastolic values are in two different categories belong to the higher group. This is the first time since 2003 that the hypertension definition has been modified.

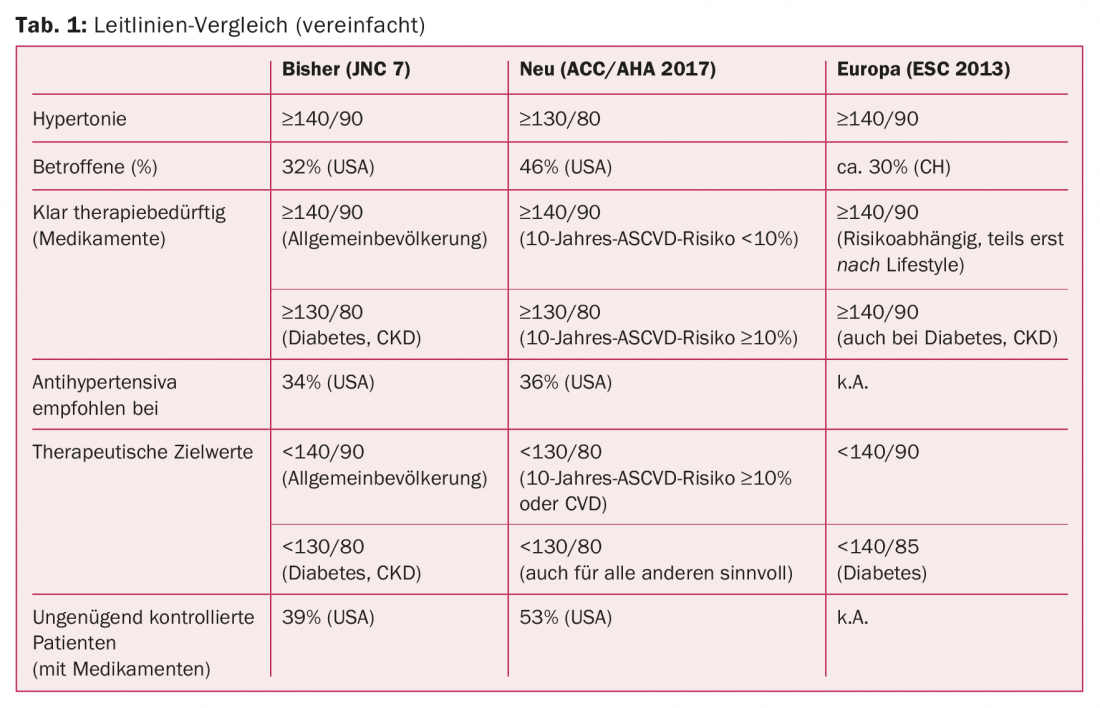

In primary prevention of patients with calculated 10-year ASCVD risk of at least 10%, 130/80 mmHg is now the threshold for drug treatment. The authors recommend the so-called ACC/AHA Pooled Cohort Equations as a risk calculator [2]. This has only been validated for the US population aged 45-79 years and without concurrent statin therapy. For the remaining affected individuals, the original values of ≥140/90 mmHg remain valid as the threshold for medication. Both are Class I recommendations. This is also in contrast to the previous guidelines, the so-called JNC 7 (Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure) [3]. There, the cutoff for antihypertensives in the general population was 140/90 mmHg. Values of ≥130/80 mmHg were considered to require therapy only in the presence of diabetes or chronic kidney disease.

The authors argue that cardiovascular risk is already significantly increased at levels above the newly defined limit. The increased risk in (redefined) stage 2 hypertension has been known for a long time, but there are now increasing data suggesting a continuum: already in (redefined) “elevated blood pressure” and (redefined) stage 1 hypertension, there is much to suggest a sensitive increase in risk. The categorization is based on observational and randomized clinical trials as well as corresponding meta-analyses, which are derived from a hazard ratio

- Between 1.1 and 1.5 for values of 120-129/80-84 mmHg vs. <120/80 mmHg

- As well as between 1.5 and 2.0 for values of 130-139/85-89 mmHg vs. <120/80 mmHg

go out. In view of this considerable increase in risk, the term “prehypertension” is misleading (because it is trivializing) and must be abandoned. The implicit criticism of the terms in the European guidelines, which still describe a blood pressure from 120 to 139 and 80 to 89 as “normal”/”high normal,” already resonates here. How long these will hold up is questionable.

Pathologization of an entire society?

With the introduction of the new guidelines, a reduction below 130/80 mmHg will also become the new therapeutic target for many patients already undergoing treatment – namely those with a 10-year ASCVD risk of at least 10% or an already known cardiovascular disease (class I recommendation). In all other hypertensive patients, a reduction below these values also seems reasonable, the new guidelines note (recommendation class IIb). Thus, the current guidelines not only pathologize large parts of Western society in one fell swoop, but also declare the current therapy of many hypertensive patients as ineffective (or more precisely: insufficiently effective). The publication itself refers to just over half of the US population as having grade 1 hypertension according to the current definition. By comparison, with the original threshold, it was already a third. The data come from a companion study [4] that was designed to examine the potential impact of the new guidelines.

Even with the new limit, lifestyle measures such as weight reduction, healthy diet, restricted sodium/increased potassium intake, exercise, or moderate alcohol consumption remain important first pillars of hypertension management, the authors argue against. This affects a large proportion of those newly defined as hypertensive, he said. Consequently, only a small increase in drug prescriptions in this area would be expected (recommended at former 34% and new 36%) [4]. In addition, blood pressure measurements at only one visit are still too often taken as the basis for prevalence calculations. This would overestimate the prevalence of hypertension. According to these and previous guidelines, at least two measurements in at least two visits are required. The extent to which this standard rule is followed in practice and in prescribing is unclear, he said.

The definition of a healthy blood pressure remains the same, the Americans added. Whereas in the past the so-called “prehypertension” (120-139/80-89) was supposed to be a warning signal for physicians to pay special attention to blood pressure, today it is already an “elevated” systolic blood pressure of 120-129.

The authors do, however, make one concession to their critics: it can indeed be assumed that a considerable proportion of those already receiving treatment will have to be treated more aggressively in order to achieve the target values. 53% would be newly above that, compared with 39% with the original definition [4].

Opinions differ

In Europe, the old blood pressure values remain in place for the time being. However, the U.S. “rush to the front” is also causing a lot of discussion here, with quite controversial views. Where there is a diagnosis, a therapy is always obvious, and since the lifestyle measures mentioned time and again are anything but simple “wellness” measures, but for many require considerable discipline and mean restrictions in everyday life, the desire for a supposedly simple solution with medications will quickly be in everyday practice.

Despite all this, lower target values are probably to be expected in this country soon as well; the ESC is currently working hard on a new guideline to replace the previous one from 2013 [5]. It is expected to be ready in the summer of 2018. So it remains exciting.

Finally, it should be noted that the new U.S. guidelines not only contrast with the current European ones, but also in some ways represent a departure from JNC 8 [6], the controversial successor to JNC 7, which went in exactly the opposite direction, toward a self-described “relaxation” of limits. According to JNC-8, patients over 60 years of age did not need to be treated and reduced to these target values until 150/90 mmHg. Although this did not mean that all patients currently achieving lower values should be readjusted to higher ones, but rather that even a reduction to below 150 would bring a good benefit, it seems difficult to reconcile with the basic tenor of the new guidelines. Here, the limit of 130 mmHg clearly also applies to older persons, more precisely to noninstitutionalized ambulatory and community-participating hypertensives of 65 years or older (class I recommendation). In cases of high comorbidity burden and limited life expectancy, an individualized approach would be preferable (Class IIa).

The discussion has thus only just begun and will probably continue to occupy the cardiology world intensively in the future. Table 1 shows an overview of the relevant guidelines of recent years.

Source: American Heart Association (AHA) Scientific Sessions 2017, November 11-15, 2017, Anaheim.

Literature:

- Whelton PK, et al: 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. Hypertension 2017 Nov 13. DOI: 10.1161/HYP.00000000000065 [Epub ahead of print].

- ACC/AHA Pooled Cohort Equations. http://tools.acc.org/ASCVD-Risk-Estimator/

- Chobanian AV, et al: Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2003; 42(6): 1206-1252.

- Muntner P, et al: Potential U.S. Population Impact of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association High Blood Pressure Guideline. Circulation 2017 Nov 13. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032582 [Epub ahead of Print].

- Mancia G, et al: 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Journal of Hypertension 2013; 31(7): 1281-1357.

- James PA, et al: 2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults – Report From the Panel Members Appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA 2014; 311(5): 507-520.

CARDIOVASC 2017; 16(6): 28-30