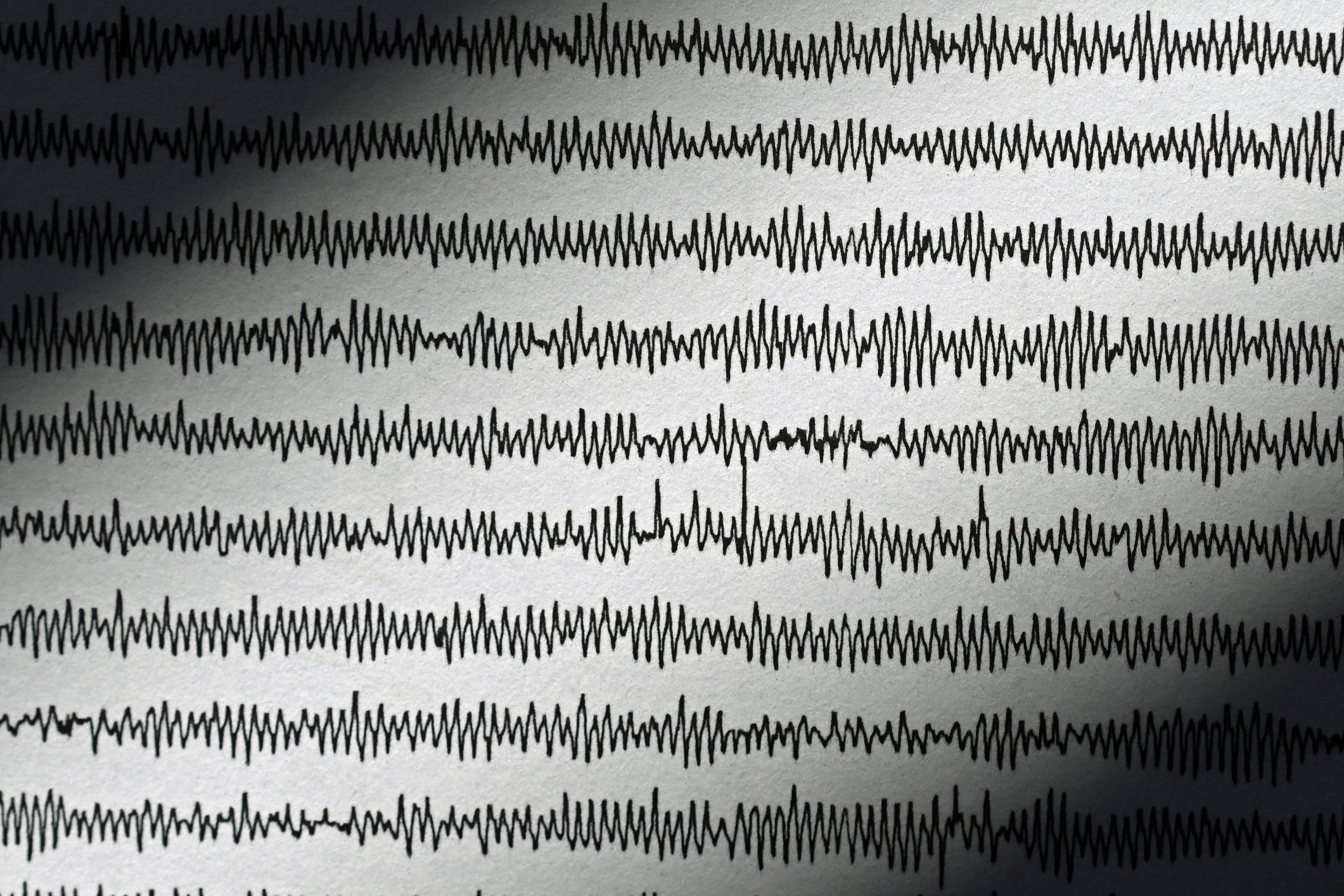

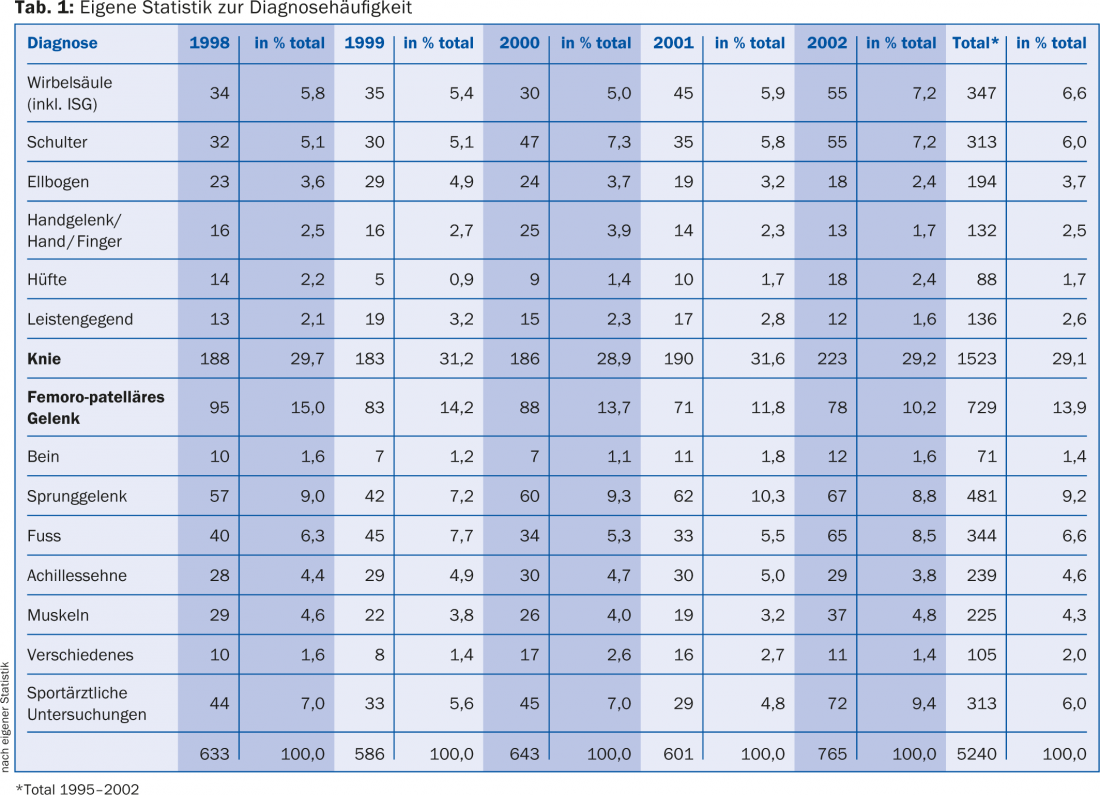

A few years ago, in statistics that have never been published, we were able to show how frequently knee pain and problems occur in the general practitioner’s office (Table 1). Consistent with many other observations, the relevant frequency of knee complaints, acute and overuse-related, in sports medicine as well as in general medicine was also confirmed. This article provides an overview by location and goes into more detail about two specific diagnoses.

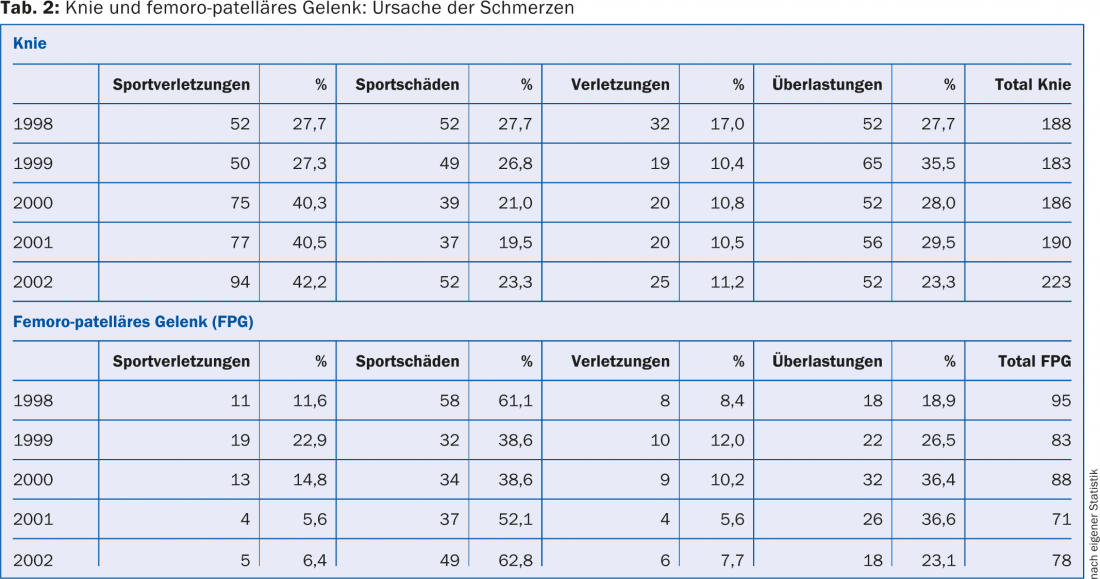

If we take a closer look at the knee drops, a picture emerges as shown in Table 2.

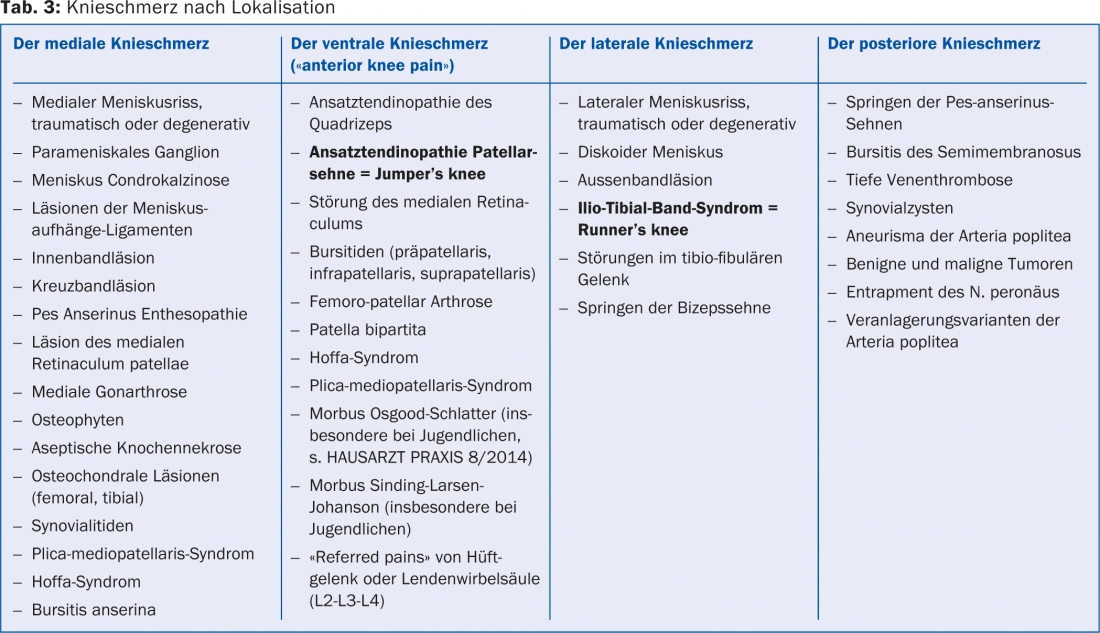

Although diagnostic imaging tools (X-ray, ultrasound, CT, MRI, SPECT) are used extensively nowadays, history taking and clinical examination remain inevitable first steps in general practice, and even the description of the localization of the complaints by the patient himself can provide important diagnostic clues (Table 3).

Knee examination

A knee must be evaluated according to a programmed knee examination protocol. It would go beyond the scope of this article to describe this knee examination in detail.

In principle, after inspection in gait and standing (then in supine) and palpation, mobility, medial and lateral stability, and “central” stability should be checked by specific tests.

At this point, we would like to emphasize what is actually “banal” palpation; by applying appropriate pressure to the base of the patella, the apex of the patella, the tibial tuberosity, the lateral femoral epicondyle, the two joint spaces and the pes anserine insertion, to name only the most important points, extremely important information is obtained. As always, the side-by-side comparison is more than recommendable. Meniscus tests must also be performed and patella function checked, always assuming that this is possible from the patient’s point of view (pain → tension). Likewise, one should test well the active competence of the extensor and flexor function, and a so-called muscle testing is also important.

Two diagnoses

According to the motto “you can’t make a diagnosis you don’t know”, we would like to select two sports-exclusive, so to speak, but not always well-known diagnoses from this variety of diagnoses and explain them in a little more detail.

Jumper’s Knee: Jumper’s knee is also called patellar tendinitis and is clearly one of the ventral knee conditions. It is a painful chronic overuse of the attachment of the patellar tendon to the inferior patellar pole and, in keeping with its name, is often diagnosed in jumping sports. It should be mentioned here that there is a similar clinical picture in younger athletes still growing, a growth disorder called Sinding-Larsen-Johanson.

The affected person is usually able to describe his problem quite precisely: He has very precisely localizable pain at the tip of the patella, which in the first phase (grade I) occur only after stress, then may also be present at rest (degree II). The rarely occurring grade IV corresponds to a tendon rupture.

On clinical examination, this pain can be reproduced very easily. X-rays are mainly used for differential diagnosis. Ultrasound can reveal edema, thickening of the tendon, and degenerative changes in the sense of dissolution of the parallel collagen structure, especially in the dorsal portion of the tendon. On duplex, signs of neovascularization are sometimes seen.

Treatment, mainly conservative, is protracted from stage II onwards. So far, no therapy has proven to be clearly better than the others: Modulation of stress (does not mean unfit for sports!), physiotherapeutic measures such as ultrasound, fascia techniques, radial or focused shock wave therapy, sclerotherapy treatments (e.g. with polidocanol), local injections of autologous blood (PRP=Platelet Rich Plasma), of hyaluronic acid or classically of cortisone are among the most commonly used treatments. Surgery is reserved for the fewest cases as ultima ratio, so to speak.

Sports medicine is prevention: maintaining good mobility through stretching exercises should be “inculcated” especially in young people.

Runner’s Knee: Scheuer‘ s syndrome, or more specifically Ilio-Tibial Band Friction Syndrome (ITBFS), is a clear lateral knee pain as an expression of an overuse condition common in runners, but also cyclists and other athletes.

This pathology occurs because the finer part of the tendon of the tensor fascia latae muscle is located in front of or behind the lateral femoral epicondyle, depending on the position of the knee and hip; in other words, it constantly rubs against this bony prominence. This can cause irritation of the local structures involved (periosteum, bursa, tendon). This unfavorable situation can occur even more when the said muscle is “shortened”, causing abnormal tension on its particular long tendon.

The diagnosis is predominantly clinical. The athlete can also define the pain point well in this case, the pressure awakens the discomfort – even more so when knee flexions and extensions are required in this situation. The so-called Ober test, a muscle testing maneuver, indicates the same. X-ray is used to exclude other pathologies (stress fractures), sonography may possibly show the irritated bursa or damaged tendon.

Treatment is primarily conservative. Local measures (ultrasound, shock wave therapy), possibly infiltrations (PRP, steroids), but especially stretching exercises of the M.tensor fascia latae and the M. vastus lateralis as well as strengthening exercises of the hip rotators seem to be the most important steps. In the case of leg length differences, it is worth compensating for them. In rare cases, surgical Z-plasty (tendon lengthening) is suggested.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(11): 11