After acute treatment in the center hospital, the therapy of infarct patients is not complete. In addition to lifestyle changes, treatment of blood pressure, cholesterol, or any heart failure, antithrombotic therapy must be a focus. An overview of current follow-up care relevant to practice.

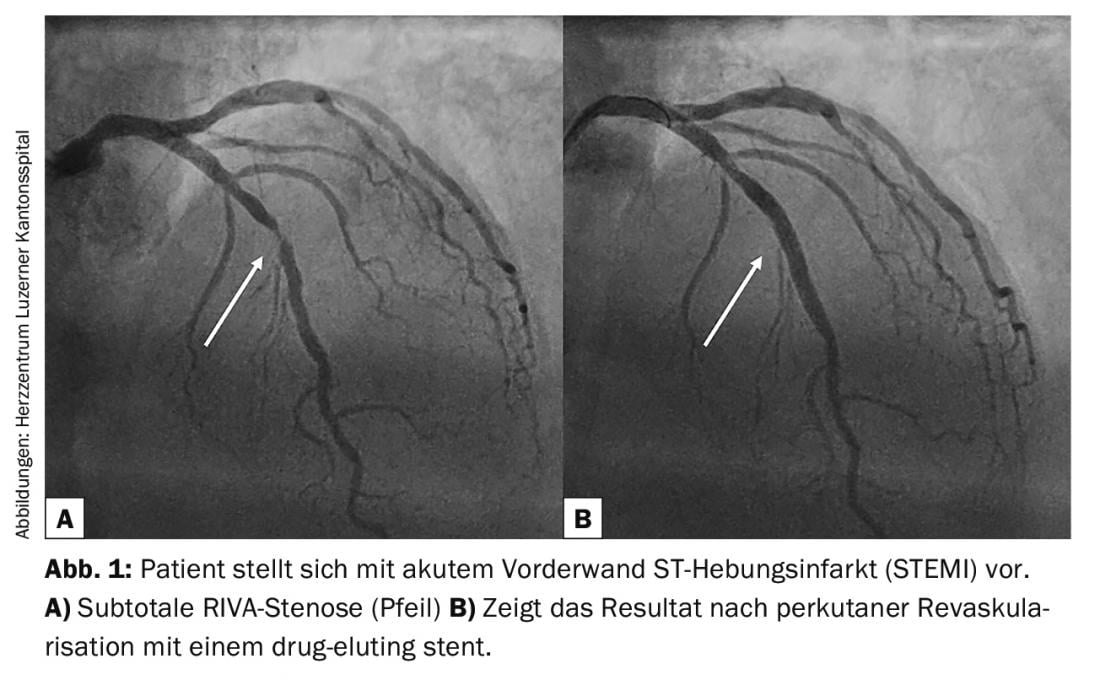

Thanks to rapid revascularization of infarcted patients in center hospitals, more people than ever survive acute myocardial infarction (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, the treatment of infarcted patients is not completed when they leave the hospital. Lifestyle changes, treatment of blood pressure, cholesterol or possible heart failure require regular monitoring and continuous adjustment of therapy in the practice, especially in the early phase. In addition, antithrombotic therapy has become much more complex thanks to the availability of new drugs. The following article is intended to provide you with an up-to-date, practical summary of the follow-up care of infarct patients in the office.

Lifestyle changes

Despite the availability of many medications, changes in certain daily habits are still highly effective in secondary prevention. As the phrase “everyday habits” suggests, such habits do not take place in the hospital, but in everyday life. Therefore, effective therapy can only take place to a limited extent in the inpatient setting. On the contrary – this is the domain of primary care physicians and outpatient cardiac rehabilitation. Key lifestyle changes include quitting nicotine and exercising regularly.

Nicotine cessation leads to improvement of endothelial function, reduction of radical formation, and reduction of prothrombotic factors and inflammation. Thanks to all these positive effects, nicotine cessation is the most effective measure to prevent further events in patients with myocardial infarction. It reduces the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and all-cause mortality by over 30%. Generally, the earlier in life a nicotine stop occurs, the more effective. But older patients also benefit. In addition to counseling therapy, nicotine replacement procedures and other medications are available today [1].

Equally important is regular physical activity. Patients should be motivated to participate in an endurance sport for rehabilitation, but also in the long term. Pedometers can also motivate patients to exercise more after infarction. The guidelines recommend five 30-minute workouts per week at a moderate load. Medium stress includes, for example, rapid walking as used in Nordic walking. However, there is also evidence that excessive training, such as training for competitions in postinfarction patients, may increase mortality. This circumstance is probably due to the stress peaks with increased risk of plaque rupture [2].

Regarding nutrition, the books are not closed yet. But what you can say for sure is: balanced, enough fruits and vegetables, little saturated fat and not too much.

Hypertension therapy

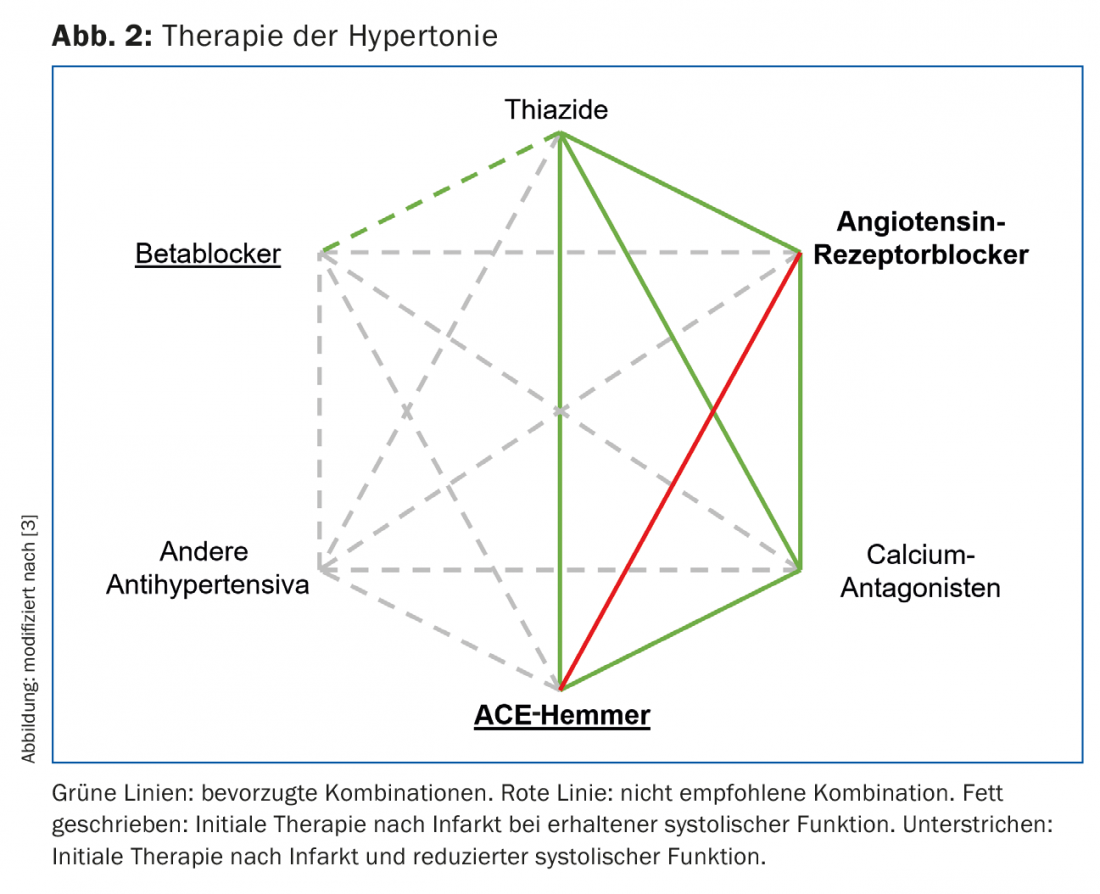

In Europe, about 40% of adults have elevated blood pressure. Hypertension is defined as a blood pressure at rest ≥140 mmHg systolic and/or ≥90 mmHg diastolic. If white coat hypertension is suspected, it is recommended to perform a 24h blood pressure measurement. Long-term hypertension leads to atherosclerosis and end-organ damage to the heart, brain, kidney, and eye. In particular, the risk of stroke increases practically linearly with elevated systolic blood pressure. Therefore, a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg should always be treated in postinfarction patients who are at very high cardiovascular risk per se [3]. The preferred initial therapy in patients after myocardial infarction is the ACE inhibitor or AT-1 antagonist. If heart failure is also present, a beta-blocker should be added and a mineralocorticoid antagonist should be considered (cf. below and Fig. 2). Therapy should be reviewed every 2-4 weeks and adjusted if necessary. The blood pressure target is generally <140/90 mmHg (for diabetics <140/85 mmHg). In patients over 80 years of age, one may also be somewhat more generous and aim for a blood pressure target of <150/90 mmHg.

Therapy of hypercholesterolemia

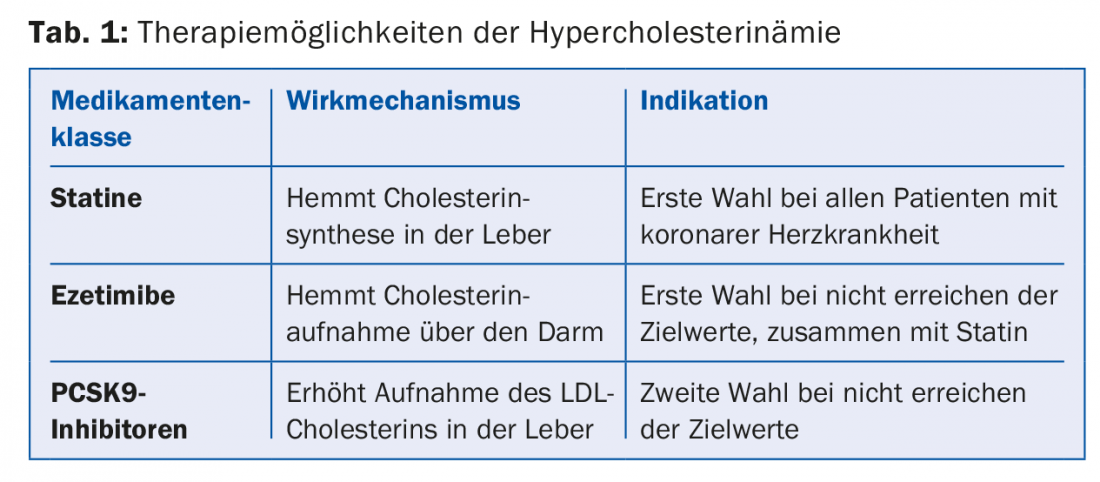

In a large meta-analysis, each reduction in LDL cholesterol of 1 mmol/l was shown to reduce the risk of a cardiovascular event by 20%, and all-cause mortality by 10% [4]. According to current European recommendations, postinfarction patients should reduce LDL cholesterol to <1.8 mmol/l or at least aim for a decrease of >50% [5]. In principle, all infarct patients should be treated with a statin. Because of superior efficacy, either atorvastatin or rosuvastatin is recommended here. If a statin is not sufficient or is not tolerated, for example, because of muscle pain (approximately 5-10% of all patients), the administration of ezetimibe 10 mg/day should be considered. A combination preparation with atorvastatin is now also available. A third option is the addition of a PCSK9 inhibitor, although there are still certain limitations (Tab. 1). In the recently published FOURIER study, LDL cholesterol was reduced by 1.6 mmol/l by the biweekly parenteral administration of evolocumab (PCSK9 inhibitor) in addition to a statin. Similarly, the rate of myocardial infarctions and cerebral strokes was reduced by approximately 20%. However, mortality was not reduced [6]. The results of a large endpoint study with another PCSK9 inhibitor (alirocumab) are pending.

In general, it is recommended to check the success of therapy 4-6 weeks after therapy change and, if necessary, to extend therapy until the target LDL is reached. Cholesterol levels do not need to be determined fasting, as postprandial values have the same significance and are often not relevantly different from fasting values. In addition to drug therapy, a reduction in the intake of trans fatty acids, saturated fatty acids, weight reduction, regular physical activity and smoking cessation also have a beneficial effect on the cholesterol profile.

Therapy of heart failure after infarction

Fortunately, thanks to rapid revascularization, many infarct patients leave the hospital with preserved systolic left ventricular function. However, patients with impaired systolic function <40% or mitral regurgitation (especially after posterior infarction) require heart failure therapy. These include an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (Entresto®), a beta blocker, a mineralocorticoid antagonist, and diuretics if needed. Diuretics should be dosed so that the patient is euvolemic. All other drugs are prognostically significant and the rule is “start low, go slow, aim high.” All drugs used in the treatment of heart failure have the property that they also lower blood pressure. You may well accept some orthostasis or dizziness in your heart failure patients. In addition, it is the case that patients with very severely impaired systolic function always have low blood pressure. Here, the dosage of the medication must be particularly careful.

The drugs described above are virtually the foundation of drug therapy. In addition, there are a number of other therapeutic options. Digoxin can improve symptoms in many patients, and hospitalization rates have also been reduced [7]. Procoralan may be considered in patients with sinus rhythm and a heart rate >70/min despite beta-blocker therapy. Patients with heart failure also often have subclinical iron deficiency and may benefit from intravenous iron replacement therapy. In the presence of left bundle branch block and severely impaired left ventricular function, resynchronization therapy (CRT or ICD-CRT) should be discussed. Relevant mitral regurgitation can be treated surgically or percutaneously using MitraClip®.

Patients with severe heart failure should measure their weight daily to detect decompensation early and increase the diuretic dose if necessary. In the past, heart failure patients were prescribed physical rest. Today we know: moderate physical training is desirable and prognostically effective even in heart failure.

Double platelet inhibition after infarction

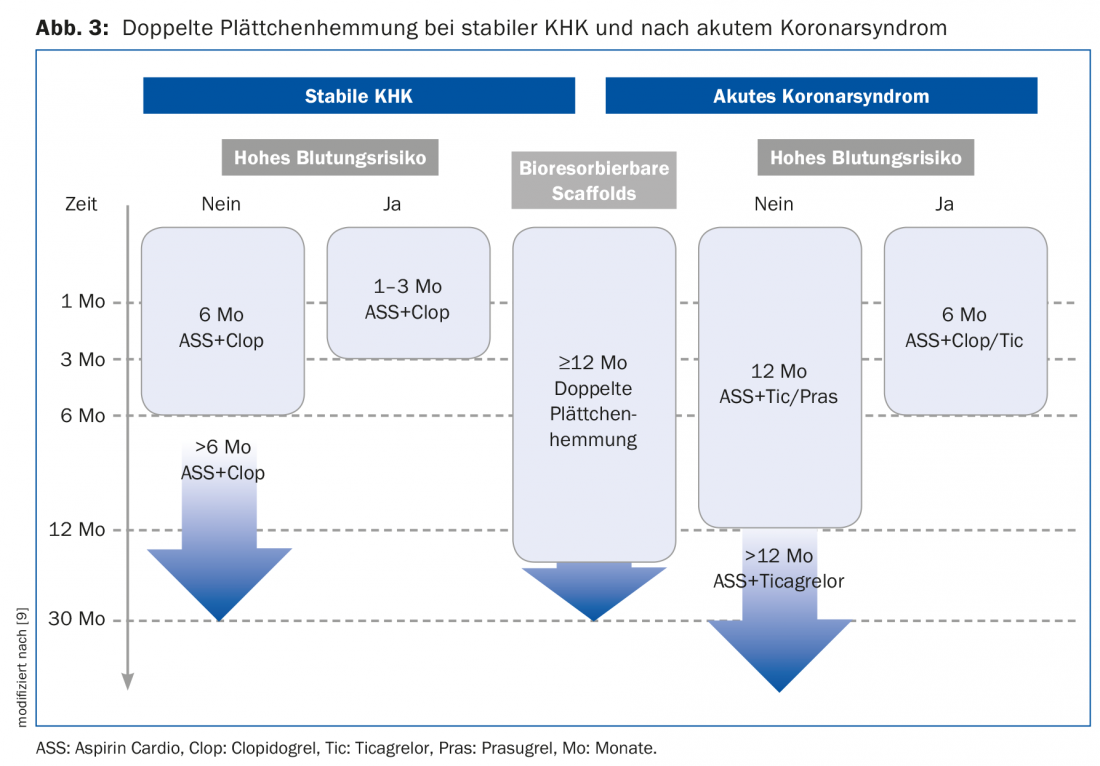

After myocardial infarction, coagulation is usually activated and patients benefit from intensified anticoagulation. Studies have shown that in the first year after myocardial infarction, the risk of a cardiovascular event is 10% despite drug therapy, and in subsequent years it is still about 4% per year [8]. Current guidelines recommend aspirin cardio indefinitely and for 12 months either ticagrelor 2× 90 mg or prasugrel 1× 10 mg or 1× 5 mg daily, respectively [9]. After this 12-month period, dual antiplatelet therapy can be prolonged with 2× 60 mg ticagrelor in patients at high risk of thrombotic events and profound bleeding risk (Fig. 3) . However, it should be noted that this is associated with an increased risk of bleeding [10]. The details of which patient groups benefit from prolonged platelet inhibition have not yet been clarified.

About 8% of patients with myocardial infarction also have atrial fibrillation. The risk of bleeding is significantly increased under triple therapy, which is why it should be used for as short a time as possible. Thereafter, dual therapy is recommended, most commonly a combination of Marcoumar and clopidogrel or rivaroxaban 15 mg and clopidogrel. After one year, the patient should then be switched to monotherapy with Marcoumar or a direct oral anticoagulant at a normal dosage. If relevant hemorrhage still occurs, atrial ear closure should be discussed in these patients.

A question that frequently arises in practice is whether dual antiplatelet therapy may be changed to aspirin monotherapy before surgery. This must be decided on an individual basis and the risk of stent thrombosis must be weighed against the benefit of surgery. Many surgeries can be performed with careful hemostasis even with dual platelet inhibition.

Summary

Patients after myocardial infarction are at high risk for further cardiovascular events and therefore benefit from drug therapy and lifestyle changes. Especially the therapy of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, but also of any heart failure, must be slowly expanded and is therefore the domain of the family practice and outpatient rehabilitation.

The most important three points that we each give to our patients are:

- Take your medication regularly!

- Move regularly!

- Do not smoke!

Take-Home Messages

- Lifestyle changes are highly effective in secondary prevention. The most important are nicotine cessation and physical activity.

- A blood pressure of ≥140 mmHg systolic in postinfarction patients at very high cardiovascular risk should always be treated. After myocardial infarction, ACE inhibitors or AT-1 antagonists are preferred.

- In postinfarction patients, LDL cholesterol should be reduced to <1.8 mmol/l or by ≥50%. All infarct patients need a statin.

- If systolic function is impaired <40% or mitral regurgitation is present, heart failure therapy is required.

- Current guidelines recommend aspirin cardio indefinitely and either ticagrelor 2× 90 mg or prasugrel 1× 10 mg or 1× 5 mg daily. for 12 months.

Literature:

- Rigotti NA, Clair C: Managing tobacco use: the neglected cardiovascular disease risk factor. Eur Heart J 2013; 34: 3259-3267.

- Williams PT, Thompson PD: Increased cardiovascular disease mortality associated with excessive exercise in heart attack survivors. Mayo Clin Proc 2014; 89: 1187-1194.

- Mancia G, et al: 2013 esh/esc guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the european society of hypertension (esh) and of the european society of cardiology (esc). Eur Heart J 2013; 34: 2159-2219.

- Baigent C, et al: Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of ldl cholesterol: A meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet 2010; 376: 1670-1681.

- Catapano AL, et al: 2016 esc/eas guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 2999-3058.

- Sabatine MS, et al: Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2017; 376(18): 1713-1722.

- Digitalis Investigation Group: The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med 1997; 336(8): 525-533.

- Stone GW, et al: A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(3): 226-235.

- Valgimigli M, et al.: 2017 esc focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with eacts: The task force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the european society of cardiology (esc) and of the european association for cardio-thoracic surgery (eacts). Eur Heart J 2017. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx419. [Epub ahead of print]

- Bonaca MP, et al: Long-term use of ticagrelor in patients with prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1791-1800.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(2): 7-10