In chronic somatic diseases, for example cancer, or after organ transplantation, there is a twofold increased prevalence of mental illness (up to 50%) compared to the average population. Comorbid mental disorders are associated with significantly worse treatment outcomes. They should therefore be diagnosed early, preferably by an integrated consultant psychiatric service, and treated appropriately.

Patients with co-existing physical and mental illnesses have received increasing attention in research and clinical settings in recent years. These patients place special demands on medical care. In many chronic somatic diseases, such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, respiratory diseases, as well as in patients after organ transplantation, etc., a twofold increased prevalence of mental diseases – compared to the average population and independent of age and gender – has been found [1, 2]. Anxiety disorders (23%), depression (21%), and somatoform disorders (15%) are most commonly reported [1]. In addition, various studies have shown that the presence of a comorbid mental disorder is associated with a significantly reduced quality of life, poorer compliance, and ultimately a poorer course of therapy, higher costs, and higher mortality [3]. Conversely, psychotherapeutic interventions have been shown to prolong survival in breast cancer patients [4].

The reasons for increased comorbidity with depression and anxiety disorders in the chronically physically ill are many: chronic illness is often associated with personal and social losses (relationships, work, financial resources), reduced physical functioning, pain, side effects of medications, and other stressful treatments. The course of the disease is often progressive and unpredictable, and future prospects are therefore limited. Dependencies on medical specialists and not infrequently also on relatives arise. Frequently, relatives are also exposed to increased stress; therefore, they not infrequently also have increased prevalences of mental illness, which is unfortunately often overlooked [5, 6].

The relationship between the physical and comorbid mental illness is not always entirely clear. Often there is a unidirectional connection, i.e. the physical illness is followed by a mental illness. In some cases, such as coronary heart disease, there is also a bidirectional relationship, whereby mental illness, particularly depression, may be a risk factor for developing coronary heart disease [7].

This paper explains the relationship between organic and psychological diseases using the example of oncological patients and persons after organ transplantation.

Psychological reactions in oncological patients

The need for psychotherapeutic support among oncology patients is probably significantly greater than the proportion of patients who take advantage of such an offer. The primary treating physicians partly lack the knowledge to inform about psycho-oncological services, partly they are not sensitized enough to recognize and address the possible need.

During the course of a cancer illness, patients and their relatives are repeatedly required to make major adjustments. They have to deal with the existential threat of a cancer diagnosis, symptoms of the disease, and side effects of therapy. In phases of remission, a way must be found to manage the risk of recurrence. Regular check-ups are a reminder of the threat of relapse. Each progression of the disease represents a new burden for patients and their environment [8, 12, 13].

The normal reaction to being told you have cancer is primarily shock. Patients report experiencing derealization and depersonalization. “I feel like I’m beside myself,” “Everything feels foreign,” or “I feel numb” are common statements. This is typically followed by a period of despair, grief and anger. Patients feel torn out of their previous world, they see no way out and lack orientation. In the next step, patients begin to activate resources, use strategies that have already helped them in difficult situations. Above all, a supportive social environment is helpful. Normally, those affected find a way to deal with the new situation within weeks. If there is a change in the situation, for example a recurrence, the process starts all over again.

Mental disorders in cancer patients

Approximately 50% of oncology patients are affected by a mental disorder during their course, and this number is higher in hospitalized patients with advanced tumor disease and poor prognosis than in outpatients. The majority of psychiatric diagnoses, about two-thirds, are for adjustment disorders, and 15% of patients have a depressive state. In hospitalized patients, delirium often occurs during the course of the disease, especially in advanced disease (e.g., cerebral tumor involvement) or during chemotherapy [13].

Adjustment disorders are often quickly reversible when patients have the opportunity, with support, to examine their concerns and problems from different angles and develop possible solution strategies. In most cases, those affected can quickly reactivate resources they are familiar with. The inclusion of the social network is very helpful. Psychopharmacological support is rarely necessary; occasionally, antidepressants such as mirtazapine are used, in low doses in off-label use, as a sleep aid or also with regard to the antiemetic and/or appetite-increasing effect.

Correctly diagnosing depression is challenging in cancer patients. On the one hand, there is overlapping of symptoms: Apathy, fatigue, loss of appetite, psychomotor slowing, or impaired concentration may be triggered by the cancer or its treatment (chemotherapy, radiotherapy). Second, a distinction must be made between a normal grief reaction to bad news and depression. Leading symptoms of depression are hopelessness, lack of interest, lack of emotional flexibility, feelings of guilt and suicidal thoughts. Symptoms such as despair, anger, anxiety, and rumination may represent a normal response and are then not an indication for the use of an antidepressant [9, 12].

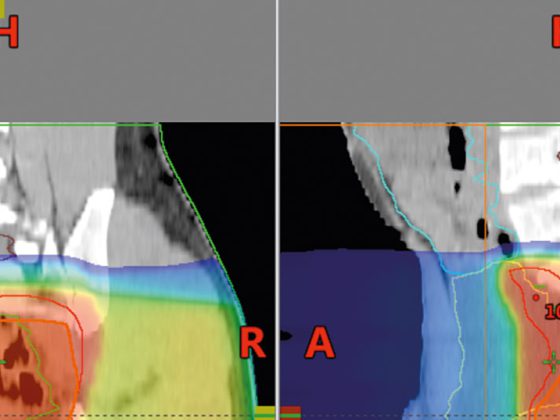

In the hospital setting or in the daily routine of primary care providers when there is little time for triage, simple, brief diagnostic tools are useful as screening procedures. Here, for example, the stress thermometer, a visual analog scale with a range from 0 to 10 (Fig. 1) , proves useful. Patients are asked whether they have suffered from psychological stress in the last week: 0 means no stress, 10 corresponds subjectively to the maximum stress [10]. With this procedure, patients with psychological distress can be identified and assigned to the appropriate specialist service (consultation and liaison service or psycho-oncological specialist service) by means of an interview.

In the presence of a depressive disorder, newer antidepressants with few side effects and few interactions are primarily used. Commonly used preparations are serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as escitalopram, citalopram, or sertraline, or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) such as venlafaxine and duloxetine [13]. Clinical pharmacologists may need to be involved.

A wide range of established psychotherapeutic procedures are also used. The topics discussed are often different from those discussed with other patient groups, and they vary by disease phase. Frequently, topics come up that have to do with coming to terms with the disease, with acceptance and integration of the disease into life. In the course, it is about finding an everyday life again, about dealing with fear of recurrence and progression, with feelings of powerlessness and helplessness. Depending on the situation, there is a confrontation with finiteness, with farewell and mourning.

The relatives of the chronically ill are often psychologically no less or even more burdened than the primary sufferers [6, 14]. There is an additional demand on the relatives to carry the system and support the patient. Quite often, there is a need for specific counseling and support services for the relatives, possibly even beyond the death of the patient. So they must also be offered psycho-oncological care.

Mental illness in transplant patients

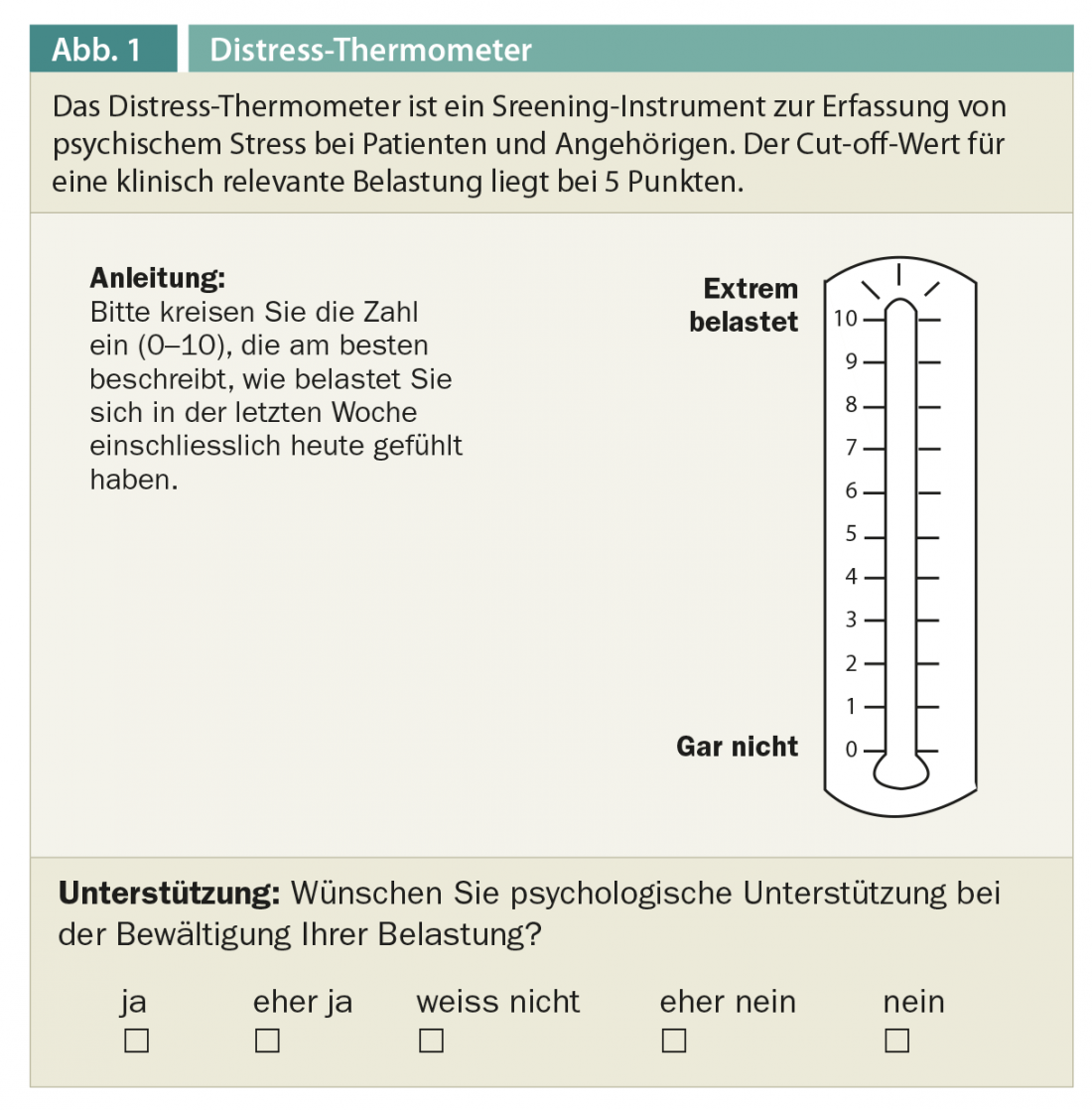

Psychosocial studies show that the quality of life of transplant patients can be significantly improved by organ transplantation [15–19]. However, the courses can be quite different [20]. Although the majority of patients benefit from transplantation in terms of their quality of life, up to 40% of patients may also be psychologically worse after transplantation (Fig. 2).

It is not necessarily the physical course after transplantation that seems to have a decisive influence on the quality of life, but rather the psychological vulnerability of a person [21]. The fact that a significant number of transplant patients report a deterioration in quality of life and that it is primarily psychosocial factors that influence this deterioration points to the importance of psychosomatic care for these patients.

Before transplantation

Patients prior to organ transplantation have a comparatively high prevalence or incidence of mental disorders. Lang et al. found a mental disorder in 32.8% of all patients prior to lung, liver, heart or kidney transplantation [22]. These are brain organic disorders, for example, as a result of hepatic encephalopathy, depressive disorders and anxiety reactions in the context of adjustment disorders, and previous addictive disorders, especially in patients with liver disease [23, 24]. Limited social support, loss of occupational integration, and financial problems are typical psychosocial stresses experienced by patients on the organ transplant waiting list [25].

Above all, however, the uncertainty as to whether and when a suitable organ will be available is a key stress factor, especially for patients for whom no substitute procedure (dialysis) or living donation is possible. If no suitable organ can be found, the dying process that begins is often influenced to the very end by the hope of still being saved by the transplant. This dilemma – the confrontation with dying and the hope of survival – determines the subjective state of the patient, but also the therapeutic relationship [26]. Accordingly, the supervising psychiatrist/psychologist may follow two lines:

- An attitude that is hopeful and forward-looking in order to actively support the patient in his fight for survival.

- Openness to the subject of dying, which makes it possible to name existential fears and to open up a psychological space in which both the hope of survival and the confrontation with the finiteness of life find their place.

Of course, antidepressant and anxiolytic medications can provide additional relief. For patients on the waiting list, it is recommended that these medications already be coordinated with immunosuppressants after transplantation with regard to the risk of interaction. As with psycho-oncology patients, some medications with few side effects have become established. Due to the frequently impaired hepatic or renal elimination, lower dosages, regular level controls and controls of blood parameters in close coordination with the somatic treatment providers are often indispensable. Benzodiazepines are avoided whenever possible in view of the addictive potential and respiratory depression. Thus, non-drug methods for anxiety and tension reduction have an important role to play.

After transplantation

In most studies, psychological well-being improves significantly after organ transplantation. However, the incidence of mental disorders varies from study to study; for example, data for anxiety disorders range from 3% to 33% [24]. Typical disorders include postoperative delirium, depressive illness, and anxiety disorders [24, 27]. Delirium is among the most common psychiatric complications in the days following organ transplantation [27]. It should be recognized early to avoid the development of a full-blown syndrome and usually resolves after a few days of careful neuroleptic treatment (e.g., haloperidol).

In the psychopharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders and depression, care should be taken to minimize the interaction profile with the immunosuppressants – preferably in consultation with the treating transplant physicians.

In the days or weeks following an organ transplant, a psychological crisis may also occur, accompanied by feelings of helplessness and abandonment [28]. Typically, panic-like feelings of anxiety occur. Often, it is found that these patients already had traumatic experiences of loss in their previous history, which are reactivated with the loss of the old organ and the unfamiliarity with the transplanted organ. A first therapeutic measure is to establish as stable a relationship framework as possible so that the affected patients can explore and test out the uncertain terrain with the new organ step by step. In this setting, traumatic fears can be addressed, and it may be possible to establish a connection between previous experiences of loss and the current, threatening situation already during the crisis.

Perhaps one of the greatest challenges is self-destructive tendencies of patients [29]. In every transplant center, patients are reported to be near death or even die because they take their medications unreliably or at times not at all. With Freud, one could speak of a conflict between the life and death instincts of a patient who on the one hand says yes to transplantation, but then does not reliably take the necessary medication [30].

One can explain this contradiction. Every individual experiences intense needs from birth, namely to be cared for, nurtured, perceived and loved. If these needs are not or only very insufficiently satisfied, we resort to a radical solution to end this state of frustration: We abolish our needs; “disobjectification” takes place [31, 32]. In clinical practice, the combination of current failure (e.g., regarding complications, limited ability to work, etc.) and early experience of frustration is shown to cause patients to withdraw and abandon all or part of their self-care. This often insidious disobjectification is basically no less risky than a physical rejection.

The challenge for physicians and psychologists is to intervene helpfully in this conflict between life affirmation and life denial and to turn the tide for the better as early as possible. If a genuine relationship can be (re)established, then over time one will be able to work through both frustrations, the original and the current, and find a new approach to a life-affirming attitude with the patient. Therein lies one of the essential tasks of the consultant psychiatrist in transplant medicine – to strengthen the vitality of patients and enable them to deal successfully and more calmly with inevitable health and psychosocial frustrations.

Literature list at the publisher

Further reading:

- Härter M, et al: Increased 12-Month Prevalence Rates of Mental Disorders in Patients with Chronic Somatic Diseases. Psychother Psychosom 2007; 76(6): 354-360.

- Zwahlen D, et al: Adopting a family approach to theory and practice: measuring distress in cancer patient-partner dyads with the distress thermometer. Psycho-Oncology 2011; 20(4): 394-403.

- Herschbach P, Heußner P (eds): Introduction to psycho-oncological treatment practice. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta 2008.

- Goetzmann L, et al: Psychosocial profiles after transplantation: a 24-month follow-up in heart, lung, liver, kidney and allogeneic bone-marrow patients. Transplantation 2008; 86: 662-668.

- Goetzmann L, et al: Psychosocial vulnerability predicts outcome after an organ transplant – results of a prospective study with lung, liver and bone marrow patients. J Psychosom Res 2007; 62: 93-100.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2011; 9(5-6): 50-54.