The majority of this year’s Zurich Dermatological Training Days was devoted to skin appendages. For the topics “News on Acne” and “Acne inversa”, Prof. Dr. med. Martin Schaller from Tübingen, Germany, and Prof. Dr. med. Gregor Jemec from Roskilde, Denmark, were invited as guest speakers. As proven experts, both gave insights into therapy and discussed current points from research.

Among experts, recognized pathogenetic factors in the development of acne mainly concern the sebaceous glands as endocrine organs. Seborrhea, de-differentiated keratinization of the epithelium of the glandular exits and colonization with Propionibacterium acnes are also the starting points of most therapy options. Propionibacterium acnes induces the formation of inflammatory mediators such as TLR2, IL-1Beta and TNF [1].

The milk lie

Prof. Dr. med. Martin Schaller, Senior Physician at the University Dermatology Clinic in Tübingen, discussed the role of nutrition in acne in his presentation. As yet, this issue is not addressed in the guidelines. However, the dogma that food and acne have nothing to do with each other is being challenged by recent research, he said. The topic of milk and acne has made it into prime time media with titles such as “The Milk Lie,” for example. A study of more than 47,000 nurses [2] and two prospective cohort studies of more than 10,000 teenagers showed a significant association between acne and milk consumption, especially low-fat milk. Cow’s milk contains bioactive hormones, milk consumption leads to an increase of 10-30% in insulin-like-growth-factor (IGF-1). IGF-1 increases have been shown to correlate with increased sebum production.

Research from 2012 demonstrated that glycemic load is of great importance. Consuming milk/ice cream more than once a week increases the risk of acne more than fourfold. The risk is not increased with yogurt, cheese, chocolate, and nuts [3]. Significantly fewer inflammatory or noninflammatory lesions in the hypoglycemic group (fruits, vegetables, fish, whole-grain bread) were also found by Kwon et al. [4].

Prof. Schaller’s conclusion for clinicians and practitioners: A connection between acne and food can no longer be ruled out. For milk and acne, a confirmation of an association was currently found in studies (OR 1.16 to 4). However, the overall data are inconsistent regarding dairy products: hypoglycemic diet has a significant positive effect, but this is clinically insufficient (decrease in noninflammatory lesions by 27.6% in the diet group and 14.2% in control group; decrease in inflammatory lesions by 29.1% in the diet group only).

Acne in rare syndromes

Acne may also occur as part of rare syndromes. SAPHO syndrome, for example, is a disorder characterized by specific features (see box).

Hereditary periodic fever syndrome and PAPA syndrome also belong to this group. In the latter, anakinra, which is not yet approved in Switzerland, is effective [6].

If there is an unusual expression or course of acne, or if there is resistance to therapy, endocrine causes such as late-onset AGS and polycystic ovary syndrome should be clarified.

Low-dose isotretinoin as preferred long-term therapy.

For Prof. Schaller, the cornerstone of topical therapy for acne is always a combination therapy of antibiotic and benzoyl peroxide or antibiotic and retinoid. Topical or systemic antibiotic monotherapy was not an option [1]. “Doxycycline is the systemic antibiotic of first choice in the therapy of acne. However, always clarify the phototoxic effect,” emphasized Prof. Schaller.

“Since no advantage of isotretinoin in conventional dose (0.5-1 mg/kg bw) has been shown over low-dose isotretinoin at 10-20 mg daily [7], I prefer low-dose isotretinoin because of good tolerability and efficacy. This is my preferred long-term therapy for rosacea-like medicinal exanthema by epidermal growth factor receptor or tyrosine kinase inhibitors.”

Therapy of acne inversa

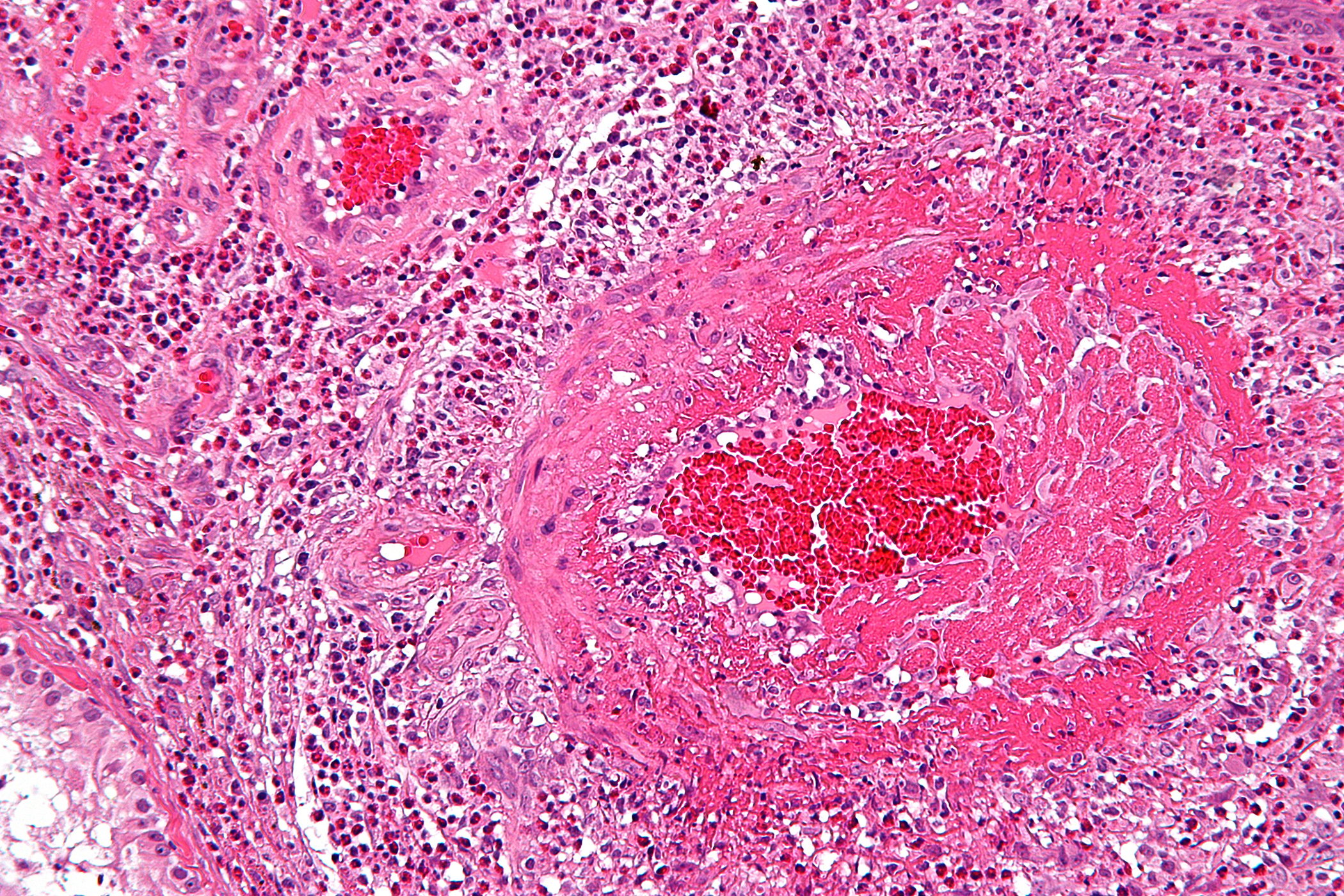

Hidradenitis suppurativa or acne inversa is a multifocal disease that begins in the outer root sheaths of the terminal hair follicles, preferably in intertriginous areas. Three phenotypes have recently been described:

- An axillary mammary type predominantly in women

- A follicular type in men with acne

- The gluteal type also predominantly in males [8].

Inflammation of the sweat glands is secondary. “Compared with other dermatological diseases, hidradenitis suppurativa is one of the most burdensome and quality-of-life-lowering diseases of all,” emphasized Prof. Gregor Jemec, MD, of the Department of Dermatology at Roskilde Hospital, Denmark. Inflammation and scarring, disfigurement, pain, discharge and odor are a tremendous burden for patients. The majority report pain from 4/10-10/10 on the pain scale [9]. Weight loss and smoking cessation can lead to improvement in the disease, but this is not true for all patients.

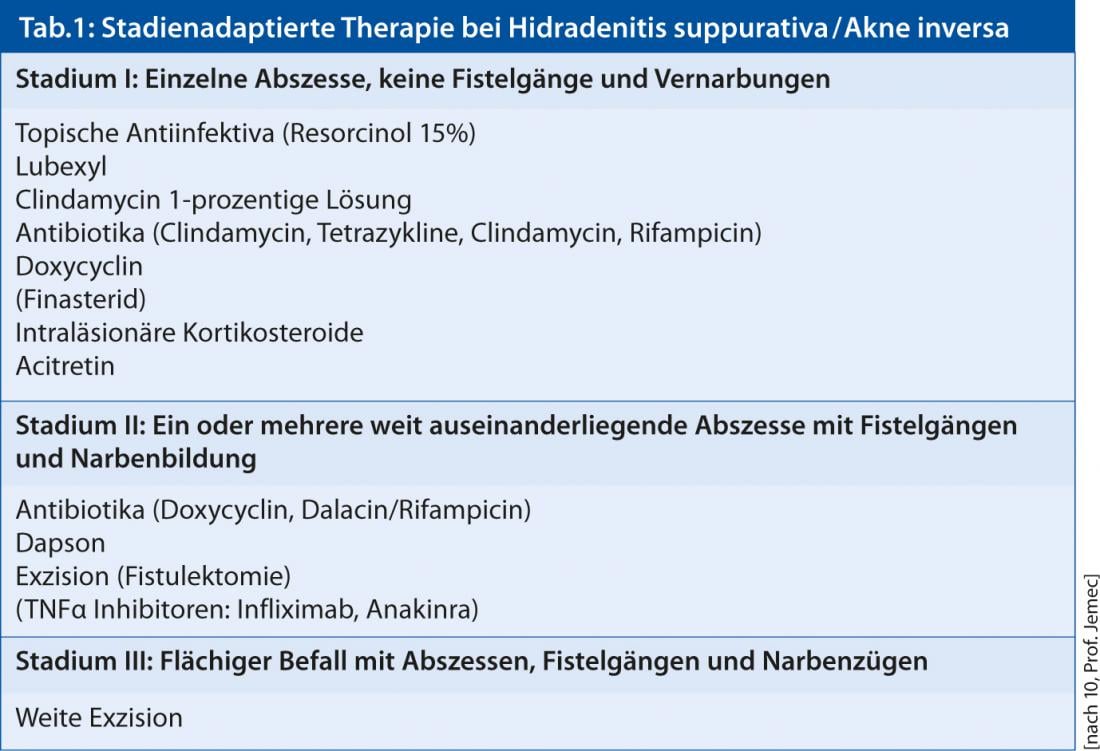

Unfortunately, drug therapy is often disappointing, Prof. Jemec acknowledged (Table 1) . Locally mild forms can be treated topically with, for example, resorcinol 15% or clindamycin 0.1% or minor surgery (excision or ablation, “de-roofing”). Numerous widely disseminated inflammatory lesions require systemic therapy (rifampicin plus clindamycin, dapsone, cyclosporan, infliximab, adalimumab).

Antibiotics with immunomodulatory properties such as clindamycin and rifampicin may be used preferentially. “The anti-inflammatory treatment approach can be followed over time, similar to other inflammatory dermatoses,” Prof. Jemec said. Penicillins are indicated primarily when superinfections are suspected. However, infections are usually secondary. Among retinoids, acitretin is more suitable; oral isotretinoin is ineffective [10].

Surgical therapy remains the only therapeutic option for hidradenitis suppurativa, providing definitive resolution in many cases. Scarring disease is the domain of surgery (excision or evaporation of lesions).

At the University Hospital Zurich, local fistulectomy under local anesthesia is performed especially in Hurley stage II and in the presence of persistent, recurrent solitary lesions. Since direct closure of the wounds (p.p. healing) results in high recurrence rates and secondary healing (p.s. healing) of the defects has a long healing time, partial adaptation of the wounds is performed as a good compromise. This procedure shows fewer recurrences and shortens

the healing period to two to four weeks.

Source: 3rd Zurich Dermatological Training Days, June 12-15, 2013.

Literature:

- Nast A, et al: European evidence-based (S3) guidelines for the treatment of acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012 Feb; 26 (Suppl 1): 1-29.

- Adebamowo CA et al: Milk consumption and acne in teenaged boys. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 58(5): 787-793.

- Ismail NH et al: High glycemic load diet, milk and ice cream consumption are related to acne vulgaris in Malaysian young adults: a case control study. BMC Dermatol 2012; 12: 13.

- Kwon HH et al: Clinical and histological effect of a low glycaemic load diet in treatment of acne vulgaris in Korean patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol 2012; 92(3): 241-246.

- Kühn F: Back pain and acne conglobata: SAPHO syndrome. Practice (Bern 1994). 2007; 96(15): 591-595.

- Schellevis MA et al: Variable expression and treatment of PAPA syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 2011; 70(6): 1168-1170.

- Mehra T et al: Treatment of severe acne with low-dose isotretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol 2012; 92(3): 247-248. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1325.

- Canoui-Poitrine F et al: Identification of Three Hidradenitis Suppurativa Phenotypes: Latent Class Analysis of a Cross-Sectional Study Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2013; 133: 1506-1511.

- Smith HS et al: Painful hidradenitis suppurativa. Clin J Pain 2010; 26(5): 435-444.

- S1 Guideline on the Therapy of Hidradenitis suppurativa/Acne inversa Christos C. Zouboulis et al, Valid until 12/31/2017.

www.awmf.de