Primary care physicians face some challenges. The number of very old, multimorbid patients with complex psychosocial and nursing needs is increasing. Many family physicians will retire in the next few years, and young family physicians increasingly want flexible work models in larger group practices. In addition, patients often want to stay at home and receive outpatient care for as long as possible. Added to this are factors such as technological advances and increasing cost pressure in the healthcare sector.

Primary care physicians face some challenges. The number of very old, multimorbid, polypharmaceutical pa-tients and female patients with complex psychosocial and nursing needs is increasing. Many GPs, especially in rural areas, will retire in the next few years and young GPs increasingly want flexible working models in larger group practices [1]. In addition, patients often want to stay at home and receive outpatient care for as long as possible. Added to this are factors such as technological advances and increasing cost pressure in the healthcare sector.

Against this background, interprofessional care models with new professional roles or existing professional groups with expanded competencies in primary care have become established in many countries, including the United States, Sweden, and the Netherlands. International reviews show that such models can improve access to care as well as patient satisfaction. This with at least the same or even slightly better quality of care and similar costs [2].

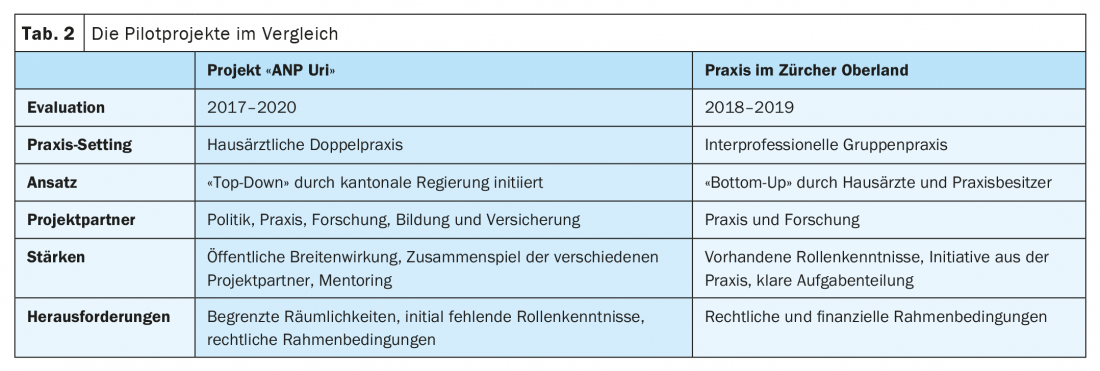

In Switzerland, new job profiles have been introduced in recent years and projects with interprofessional care models have been implemented in family practices. This article focuses on the two new professional roles of “medical practice coordinator” and “APN nursing expert” and describes their training, responsibilities, competencies, and collaboration with primary care physicians. Experiences from various pilot projects in Swiss GP practices will be included and relevant literature or study results from Switzerland and abroad will be discussed.

The job description Medical Practice Coordinator (m/f)

Since 2015, interested medical practice assistants (MPAs) have had the opportunity to train as medical practice coordinators (MPCs). In the two-year, module-based, in-service training, students can choose between a practice-based and a clinical orientation. In the practice management direction, the focus is on quality assurance in the medical practice, practice management and personnel management, and accounting. In the clinical direction, the focus is on “chronic care” management and the counseling or long-term care of chronically ill patients. Specifically, chronic respiratory diseases, coronary heart disease, and diabetes, as well as common rheumatologic conditions, dementia-related developments, and wound treatments will be addressed and explored in depth.

In family practice, MPCs with an administrative, practice management orientation often assume responsibilities in personnel management, organization, work scheduling, and quality management. They are also often more involved in the billing and financial processes of the practice. MPCs with a clinical orientation usually take on coaching roles such as nutrition or smoking cessation counseling, for example, for newly diagnosed diabetes patients. Their focus is primarily on promoting patient self-management and performing check-ups. Furthermore, MPK treat chronic wounds and can, among other things, learn dose-intensive X-rays and later perform them independently.

The job description of an APN nursing expert

In the 1960s, the concept of “Advanced Nursing Practice” (ANP) was introduced in the United States and Canada as the overarching term for advanced nursing practice. Even then, one of the motivations was to ensure better access to primary care in remote areas for vulnerable patient groups such as the elderly. The aim was also to strengthen the nursing profession and to supplement and relieve the burden on doctors working in primary care. From the 1990s, the model spread worldwide, for example in Australia, the UK, South Africa and the Netherlands [3].

An advanced practice nurse (APN), referred to in Switzerland as a nursing expert APN, is defined as “a registered nurse who, through academic training, has acquired expert knowledge, decision-making skills for highly complex issues, and clinical competencies for advanced nursing practice” [4]. Generally, by international standards, a master’s degree in nursing with an emphasis in clinical practice is considered a requirement. In many countries, especially in the USA, a distinction is also made between different APN roles. The two best known and most widely used are the Nurse Practitioner (NP) and Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) roles. CNSs specialize primarily in one specialty and usually work in an inpatient setting. They are also more involved in management and leadership roles as well as in research and teaching. NPs, on the other hand, are more involved in direct patient care and are mostly primary care providers. They may focus on a patient population (e.g., the elderly) and independently take on expanded clinical responsibilities in some countries. In some parts of the U.S., for example, they can independently prescribe medications and refer patients.

In Switzerland, education was the primary driver of the introduction of the APN role. Since 2000, it has been possible to study nursing at the master’s level [5]. Initially exclusively at the University of Basel, in the meantime at other universities and various universities of applied sciences. In this regard, the training programs have increasingly focused on clinical skills and abilities as well as pharmaceutical fundamentals, especially in recent years. Through several practicums, nursing students learn and reinforce history taking, physical examinations, ordering laboratory tests and other tests, and differential diagnostic thinking. The focus remains on holistic patient care with all nursing and social aspects.

Despite some efforts to strengthen the outpatient sector or primary care, most graduates work in inpatient settings, primarily hospitals and sometimes nursing homes. Some APNs remain in the academic setting and engage primarily in research and teaching. Only sporadically do nursing experts appear in primary care. On the one hand in Spitex organizations, on the other hand in family doctor’s practices. In family practice, the majority of nurse practitioners APNs are oriented toward the NP role and are primarily involved in direct patient care. In doing so, they may care for multimorbid, elderly patients with complex health care needs, in the office and at home as needed. In addition, they have the skills to independently care for minor emergencies, assess and adjust medication lists as necessary, and perform other tasks such as infusions or ear irrigation. Table 1 shows the basic characteristics and differences of the two job profiles MPK and nursing expert APN.

Pilot projects in Switzerland

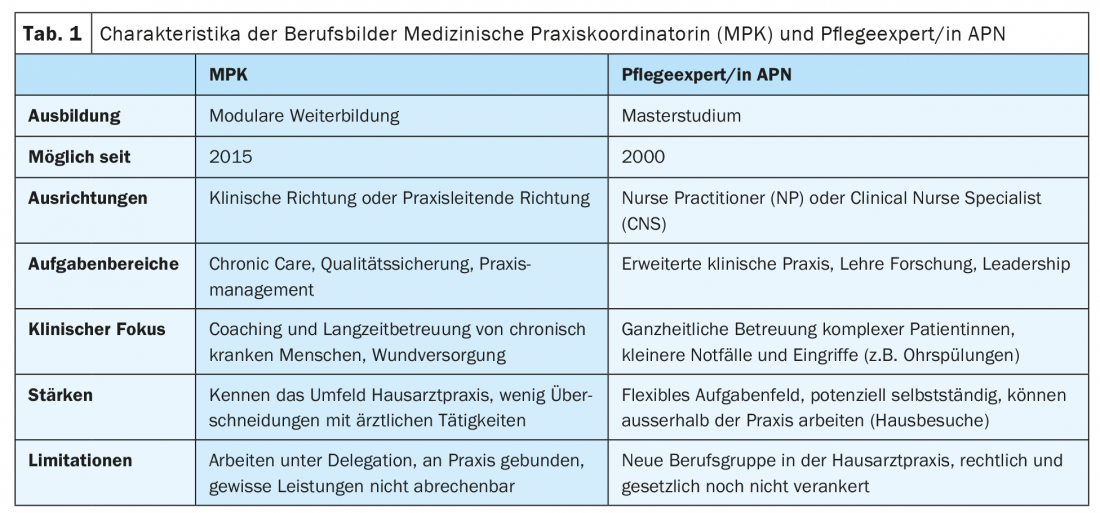

The first project with a nursing expert APN as part of an interprofessional team in the family practice was launched in Schüpfen in 2012. It was not until years later that other projects followed sporadically. In the following, two pilot projects will be described in a little more detail.

ANP Uri: In 2017, the pilot project “ANP Uri” was launched in Uri with the support of the cantonal health directorate [6]. The project was managed by the Institute of Family Medicine & Community Care Lucerne, which conducted the evaluation together with sottas formative works. Other project partners were CSS Insurance and the educational institution Careum Hochschule Gesundheit. As part of the project, a nursing expert APN with a master’s degree began working in the dual family practice in Bürglen. Simultaneously with the start of the project, the APN completed advanced training in complex care, which included physician mentoring. The three-year project aimed to evaluate the competencies, job responsibilities, and acceptance of the APN role using a “mixed-methods” approach. In addition, patient and consultation data were analyzed and legal and financial aspects were highlighted. Another focus was on the medical practice assistants or coordinators, respectively the collaboration between the primary care physicians, the APN and the MPA/K.

In the project, patients consistently showed a high level of acceptance and satisfaction with the APN role. In the practice team, clarifying roles or delineating areas of responsibility between the APN and MPA/K was especially important. The prospective MPCs in particular were unsettled at the beginning due to the unclear distribution of roles. After relatively close initial physician supervision, it became apparent that the APN was primarily able to independently provide care for elderly, multimorbid patients outside of the practice. However, the exchange with the primary care physicians continued at all times and was experienced as enriching on both sides. In the project, there was occasional resistance from the nursing homes, which were reluctant to accept the APN because of the partly unclarified legal aspects. In the practice itself, there were sometimes spatial bottlenecks and the nursing expert also had to take on everyday tasks such as flu vaccinations at times and was only able to contribute her core competencies in the psychosocial and nursing areas to a limited extent during this time.

Overall, despite some challenges, the project went very well and the APN continues to work in practice. In addition, the model could be extended to other practices, e.g. in the canton of Schwyz.

Zurich Oberland: In 2016, an interprofessional group practice hired a nursing expert APN on the initiative of the two GP practice owners. The project was evaluated in 2018/19 with the same objectives and methods as in Uri by the Institute of Family Medicine & Community Care Lucerne and sottas formative works.

Again, this showed high patient satisfaction, mainly because the APN had longer consultations and thus more time, for example, for difficult conversations. At the time of the evaluation, the team was already well-rehearsed and the areas of responsibility were relatively clearly distributed. The APN had a strong focus on complex, multimorbid patients with psychosocial problems. Nearly half of her consultations were outside the practice, and collaboration with surrounding nursing homes and Spitex went smoothly. In practice, she took on minor emergencies or ethics consultations, among other things. Medical Practice Coordinators, on the other hand, provided instruction and counseling for newly diagnosed stable diabetics. Another focus of the MPK was on the care of complex wounds.

In the meantime, the practice has hired another nursing expert APN and the interprofessional collaboration within the team continues to be very positive. Table 2 shows a comparison of the two projects.

Quality of care and division of tasks

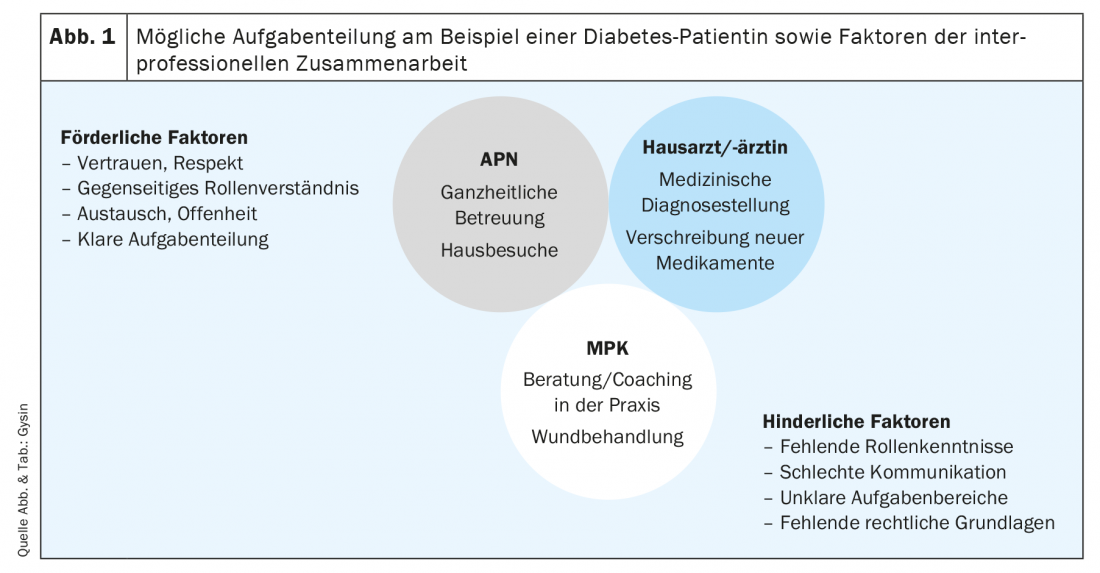

International studies, as well as the two pilot projects presented, show that better care for chronically ill people is possible through the use of nursing experts APN and medical practice coordinators in the family doctor’s office. This is also indicated by individual studies conducted in Switzerland [7,8]. In particular, patient satisfaction seems to be very high when treatment is provided by nonphysician professionals, provided they are perceived as competent confidants [9]. For successful cooperation in the interprofessional team, the mutual understanding of roles and the clear distribution of areas of responsibility seem to be decisive. One could imagine the following hypothetical case of an elderly patient with diabetes mellitus type 2 and the resulting division of tasks: The general practitioner makes the initial medical diagnosis and prescribes insulin as the drug therapy. In the practice, the newly diagnosed patient is informed by the MPK about the clinical picture and receives instructions for blood glucose measurement and application of insulin by syringe. In addition, the MPK provides the patient with nutrition and other lifestyle tips. However, since the patient lives alone at home and suffers from other chronic diseases, it is difficult to adjust her blood sugar. Now the nursing expert APN goes on a home visit and does a holistic assessment including nursing and social aspects. She looks specifically at how the patient lives, what medications she is taking, and makes small changes in dosage after brief consultation. On physical examination, the APN discovers a wound, which the primary care physician is asked to look at in the office. The following wound treatment is primarily performed by the MPK. This hypothetical patient example, along with facilitating and hindering factors of interprofessional collaboration, is shown in Figure 1.

A sensible division of tasks in the practice can relieve family physicians in their activities at certain points and supplement them with the expertise of other professional groups. Not only can this lead to better care for the increasing number of complex, multimorbid patients, but it also allows physicians to refocus more on their core responsibilities of providing medical care [10].

Challenges

In addition to a lack of role knowledge, the greatest challenge in the use of new professional roles such as the nursing expert APN and MPK remains the sometimes unclear political and legal situation. For example, the master’s degree in nursing is not yet regulated in the Health Professions Act. In addition, there are still some question marks about responsibilities and funding/billing. While there is some flexibility in pilot projects, especially when stakeholders from politics and the insurance industry are involved, concrete solutions are needed in the medium term to ensure sustainability of these novel care models.

Implications for practical projects

If you are interested in implementing new job profiles such as medical practice coordinators and/or nursing experts APN in your own practice, you need above all good role knowledge, patience and commitment. It is important that the entire practice team knows the competencies, roles and responsibilities. It is worthwhile to get in touch with existing projects in order to anticipate potential challenges at an early stage. Especially when using a nurse expert APN, it is advisable to know the level of training and previous experience in primary care. Depending on the situation, initial (medical) mentoring may be appropriate. Furthermore, it is worthwhile to meet with potential project partners, such as a health insurance company, at an early stage to clarify possible financing and billing mechanisms.

Conclusion

With the medical practice coordinator and the nursing expert APN, two new professional roles have emerged in Swiss family practices in recent years. Taking into account important factors such as mutual knowledge of roles and clear areas of responsibility, these professions can work together with primary care physicians in an interprofessional team to improve the care of elderly, multimorbid patients. In order to achieve a long-term and sustainable effect, further studies and sensible legal regulations are needed.

Take-Home Messages

- MPK and nursing experts APN are new job profiles in Swiss family practices.

- MPKs with a clinical focus may provide counseling and instruction to patients and clients with stable chronic conditions.

- APNs, as nurse practitioners with advanced clinical practice, can provide holistic care to complex, multimorbid patients in the office and at home.

- With their skills, MPCs and APNs can complement primary care physicians and improve the quality of care.

- Successful collaboration in the interprofessional team requires mutual knowledge of roles, clear areas of responsibility and, in the future, better legal foundations.

Literature:

- Promoting young talent – well on the way, but not yet there. Primary and Hospital Care 2019 (9). Available at: https://primary-hospital-care.ch/article/doi/phc-d.2019.10110.

- Laurant M, van der Biezen M, Wijers N, et al: Nurses as substitutes for doctors in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 7(7): CD001271; doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001271.pub3.

- Sheer B, Wong FKY: The development of advanced nursing practice globally. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 2008; 40(3): 204-211; doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2008.00242.x.

- NP and APN Roles – ICN Nurse Practitioner/Advanced Practice Nursing Network; 2022 [as of 02/26/2022]. Available at: https://international.aanp.org/practice/apnroles.

- Introducing advanced practice nurses/nurse practitioners in health care systems: a framework for reflection and analysis; 2008. Available at: https://lirias.kuleuven.be/retrieve/375861.

- Final report ANP Uri (abridged version) [as of: 26.02.2022]. Available at: www.ur.ch/_docn/227210/Schlussbericht_ANP_Uri_Kurzfassung_Sept2020.pdf.

- Chronic care management in family practice. Prim Hosp Care (en) 2017; 17(03): 46-50; doi: 10.4414/phc-d.2017.01418.

- Gysin S, Sottas B, Odermatt M, Essig S: Advanced practice nurses’ and general practitioners’ first experiences with introducing the advanced practice nurse role to Swiss primary care: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 2019; 20(1): 163. Available at: https://bmcfampract.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12875-019-1055-z.

- Schönenberger N, et al: Patients’ experiences with the advanced practice nurse role in Swiss family practices: a qualitative study. BMC Nurs 2020; 19(1): 90. Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12912-020-00482-2.

- Gysin S, Odermatt M, Merlo C, Essig S: Nursing experts APN and medical practice coordinators in family practice. Prim Hosp Care (en) 2020 (1). Available at: https://primary-hospital-care.ch/article/doi/phc-d.2020.10137.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(3): 6-10