Recurrent cystitis in women of all ages is becoming an increasing problem in practice – not because of antibiotic resistance, but because of constantly re-ascending host intestinal and skin bacteria. Preventing their ascension is the most demanding task of treatment. What is required is an individually adapted, multimodal concept that restores the natural defense mechanisms.

Recurrent cystitis is a very topical issue in daily practice. 50% of all women suffer from sporadic cystitis. More and more frequently, this results in recurrent inflammations – infections after every exposure to cold, after intimate intercourse or after physical and psychological stress. They affect young and old and, the longer and more frequent they occur, lead to massive insecurity and impair the quality of life at work and in leisure activities, sexuality and partner relationships.

Young women usually present with typical signs of inflammation such as bladder pain and pollakiuria. Older women, on the other hand, often do not notice these infection symptoms. They are more likely to complain of urge incontinence (OAB wet) and unpleasant urine odor, which can lead to social isolation and depressed mood. With good therapy and subsequent consistent prophylaxis, such courses are preventable and reversible. Dramatic reductions in recurrent infection rates and also long-term cures are possible. Thus, Renard et al. In a recent paper, women who had taken an oral vaccine showed a 59% reduction in episodes of infection, 36% reduction in anxiety symptoms, and 25% reduction in depressive symptoms after six months [1].

More than three infections per year

Recurrent cystitis is defined by ≥3 episodes of infection per year [2]. The infection should be proven by means of urine culture. Recurrent cystitis is usually a case of re-infection rather than pathogen persistence.

The problem of recurrent cystitis is very large, especially in adolescence and geriatrics. In our bladder and pelvic floor center, we see numerous new sufferers every day with protracted histories of suffering, whom we treat after simple clarification and instruct in prophylaxis until a cure of the inflammation or at least a relevant decrease in the frequency of recurrence is achieved. It is not so much the development of resistance that is causing us problems. Even with problem germs, the next infection is often again a banal pathogen that is sensitive to most antibiotics. Antibiotic resistance is more of a problem in other sites of infection, such as the upper urinary tract.

Impaired body defense

In the treatment and prophylaxis of recurrent lower urinary tract infections in women, we are less interested in the pathogens than in the state of the host and its defense mechanisms [3].

The infections are caused by germ ascension of pathogens of the site flora, which are naturally present in the rectum and on the skin in the intimate area. They rise through the urethra into the bladder when the vaginal flora is often disturbed. The short urethra of the woman facilitates this ascension. In simple cystitis, E. coli are the most common pathogens, accounting for about 80%; enterococci, klebsiae, and Proteus are detected less frequently [4].

Negative urine cultures?

In recurrent cystitis, the culture is often negative – in up to 50% of cases. However, this does not rule out an infection. Thus, there are pathogens that cannot be cultured in normal urine culture. Only a small proportion of such infections can be detected by other special methods (e.g. chlamydia, ureaplasma and mycoplasma). There may also be an “occult” chronic bladder wall infection that can be cystoscopically visualized as cystitis cystica. Furthermore, it may be a chronic inflammation of the periurethral Schenker’s glands, a so-called urethral syndrome with painful indurated, pressure-dolent urethra, urethral dyspareunia and typical post-coital bladder infections. Vulvar dermatoses can also cause subjective symptoms of urogenital inflammation, such as lichen sclerosus/planus or atrophy (atrophic vulvitis and colpitis). A healthy skin and mucosal barrier forms the basis for an intact urogenital defense against infection.

Three frequency peaks

There are three frequency peaks for cystitis in a woman’s lifetime.

Infants and toddlers: The first group of infants and toddlers are mostly malformations that are still undetected or not yet treated and smear infections.

Sexually active, premenopausal women: In the second group, sexually active, premenopausal women, simple cystitis is reported to have an incidence of 0.5-0.7 UTIs per person-year [5]. In the case of cystitis occurring close to intimate intercourse, this is the risk factor. We often see symptoms of a so-called urethral syndrome with a painful indurated urethra and negative urine culture in post-coital cystitis, but sometimes we also find positive urethral smears for ureaplasma, mycoplasma or chlamydia.

A striking feature of recent years has been an increase in recurrent cystitis, particularly in young women. Causes can include excessive intimate hygiene measures and tight, awkward clothing such as thongs, which can be associated with skin irritation. Furthermore, hormonal contraception, especially pills with low estrogen content, can lead to dry mucosa or disturbed vaginal environment with increased susceptibility to infections. With weakened immune defenses, we even see bladder infections with germs that are apathogenic in themselves, such as lactobacilli.

Postmenopausal women: The third group is postmenopausal women. In postmenopause, the massive drop in estrogens leads to atrophy of the vaginal skin. The consequences are a decrease in lactic acid bacteria (lactobacilli), an increase in pH and colonization of the vagina with intestinal and skin bacteria and anaerobes. These then rise slightly into the bubble [6]. There is a correlation in postmenopause between increasing age, estrogen decline, urogenital atrophy, bladder infections, urinary incontinence, cystocele, residual urinary increase, and fecal incontinence [7, 8].

With increasing age, other risk factors are added in the form of age-degenerative processes, such as immunodeficiency, multimorbidity, diabetes, rheumatologic diseases with immunosuppressive therapies, obesity, mobility disorders, intimate care problems with psychorganic syndrome or dementia, and insufficient drinking with decreased thirst.

What can the family doctor do?

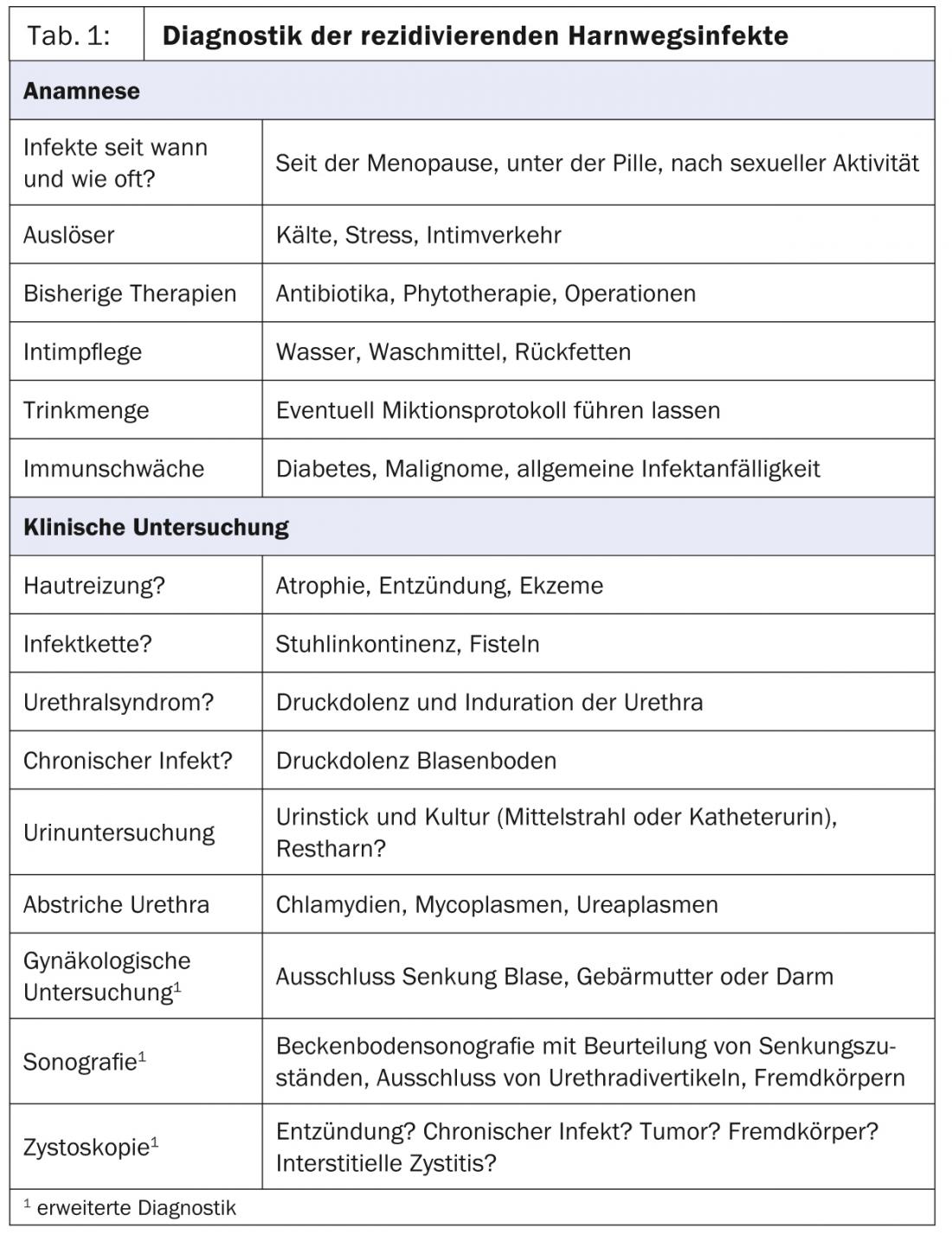

The core elements (Tab. 1) first include a targeted medical history, eliciting since when and how often cystitis occurs, e.g. after sexual activity, under the pill or since menopause. Typical infection triggers and previous therapies should be asked about, as well as intimate hygiene and drinking quantity.

This should be followed by a clinical examination. Searched for possible infection chains (vulva/vagina/urethra/bladder), e.g., fecal incontinence. Furthermore, the skin and mucosa may be assessed and examined for signs of chronic inflammation and eczematous changes perianally, vulvally, and vaginally. Urethral pressure dolences and indurations are palpated, and smears may be taken from the urethra for ureaplasma, mycoplasma, and chlamydia. A urine examination with urine culture can be performed either by means of a midstream urine or – which is more informative in the case of recurrent infections – by means of a catheter urine for additional residual urine determination. Although the urine stick is well suited for screening for the presence of a urinary tract infection, it is no substitute for a urine culture, since no statement can be made about the germ and the resistance situation.

Therapy and long-term prophylaxis

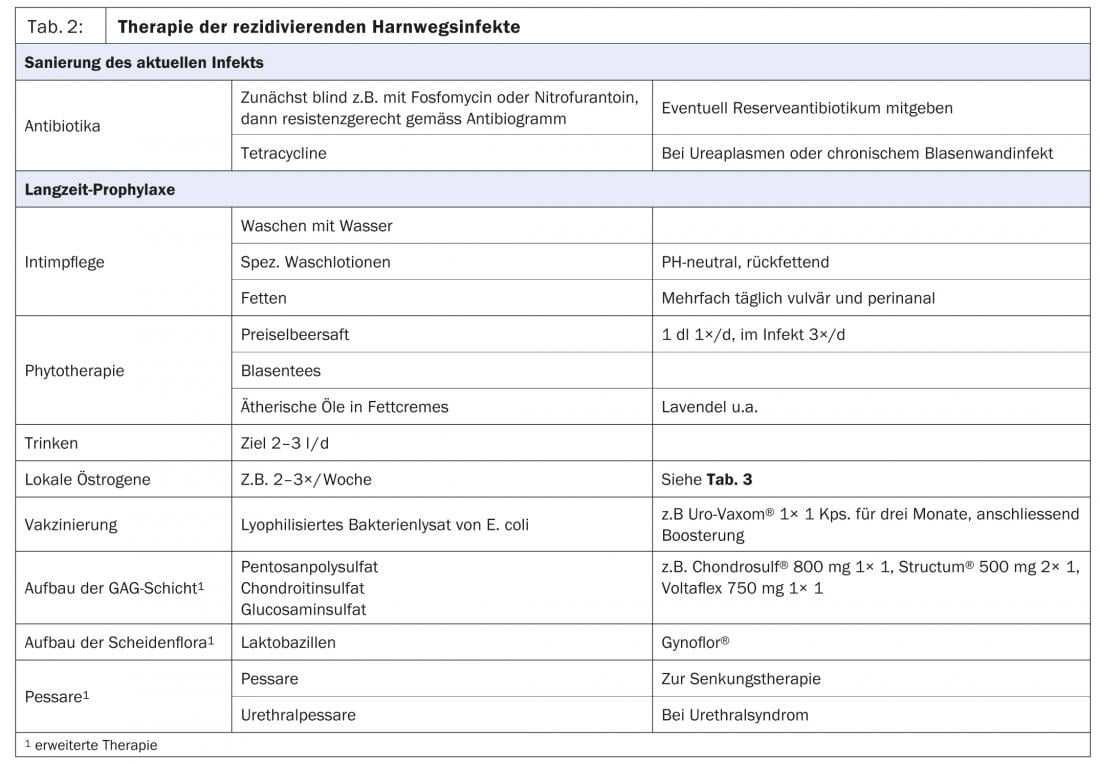

In order to achieve a cure, it is first necessary to treat the infection and then to establish long-term prophylaxis (Table 2) .

Recurrent urogenital infections should be treated initially with antibiotics or antifungal agents. So-called “blind” antibiotic therapies are suitable for unproblematic inflammations and for immediate self-treatment in case of recurrences after prolonged absence of inflammation. An antibiotic in reserve provides the patient with psychological reassurance and reduces anxiety symptoms, which may favorably influence the healing process.

This is followed by the establishment of an intact skin and mucous membrane barrier and a healthy vaginal environment. For intimate care, washing should be done with water or with well-tolerated, moisturizing, pH-neutral wash lotions (e.g. Lubex®, Der-med®, antidry®, Pruri-med®) (Fig. 2). Furthermore, we recommend regular lubrication once or twice a day vulvally and perianally.

Phytotherapeutics support the defense against infections in the bladder [9]. Cranberry juice and blister teas are used, and in skin care essential oils are used as additives in fat creams (Fig. 3).

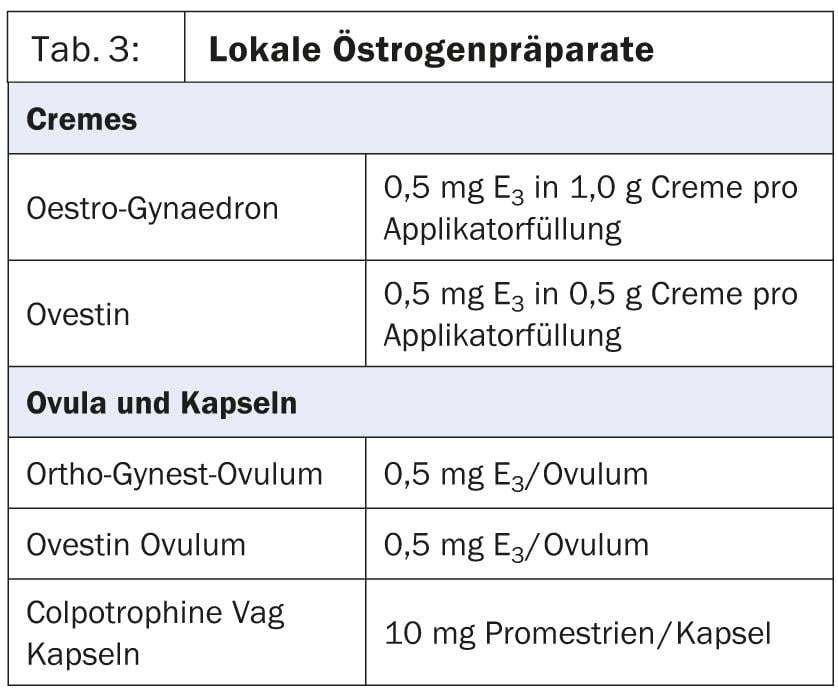

It is very important to drink a sufficient amount of 2-3 liters to flush out rising bacteria. In urogenital atrophy, local estrogenization is indicated because it can reduce the number of urinary tract infections by a factor of 10 (Table 3) [10].

Vaccination against E. coli

Vaccination, e.g. with Uro-Vaxom® against E. coli bacteria, serves as adjuvant immune stimulation and is recommended if E. coli is repeatedly detected (evidence class 1a).

According to the latest EAU recommendations, immunostimulation, e.g. with Uro-Vaxom® , is currently the best proven non-antimicrobial measure against recurrent cystitis (recommendation grade B) [11]. If these measures do not lead to success, urogynecological clarification and treatment or prophylaxis consultation is recommended. At the Bladder and Pelvic Floor Center Frauenfeld, we have developed the following concept for the diagnosis and treatment of recurrent cystitis over the last few years [12].

Advanced diagnostics

In addition to the above measures, we perform pain and inflammation localization (periurethral, vulvar or vesical) during the gynecological examination. We assess any subsidence conditions and a residual urinary problem. Very important are the skin texture and mucosal trophics. In the native specimen, we assess the cellular appearance, trophics, vaginal flora, and signs of inflammation. A residual urine measurement and a urine culture are performed by bladder catheterization. Special urethral swabs for chlamydia and ureaplasma reveal some hidden pathogens that are particularly relevant in chronic urethral symptoms.

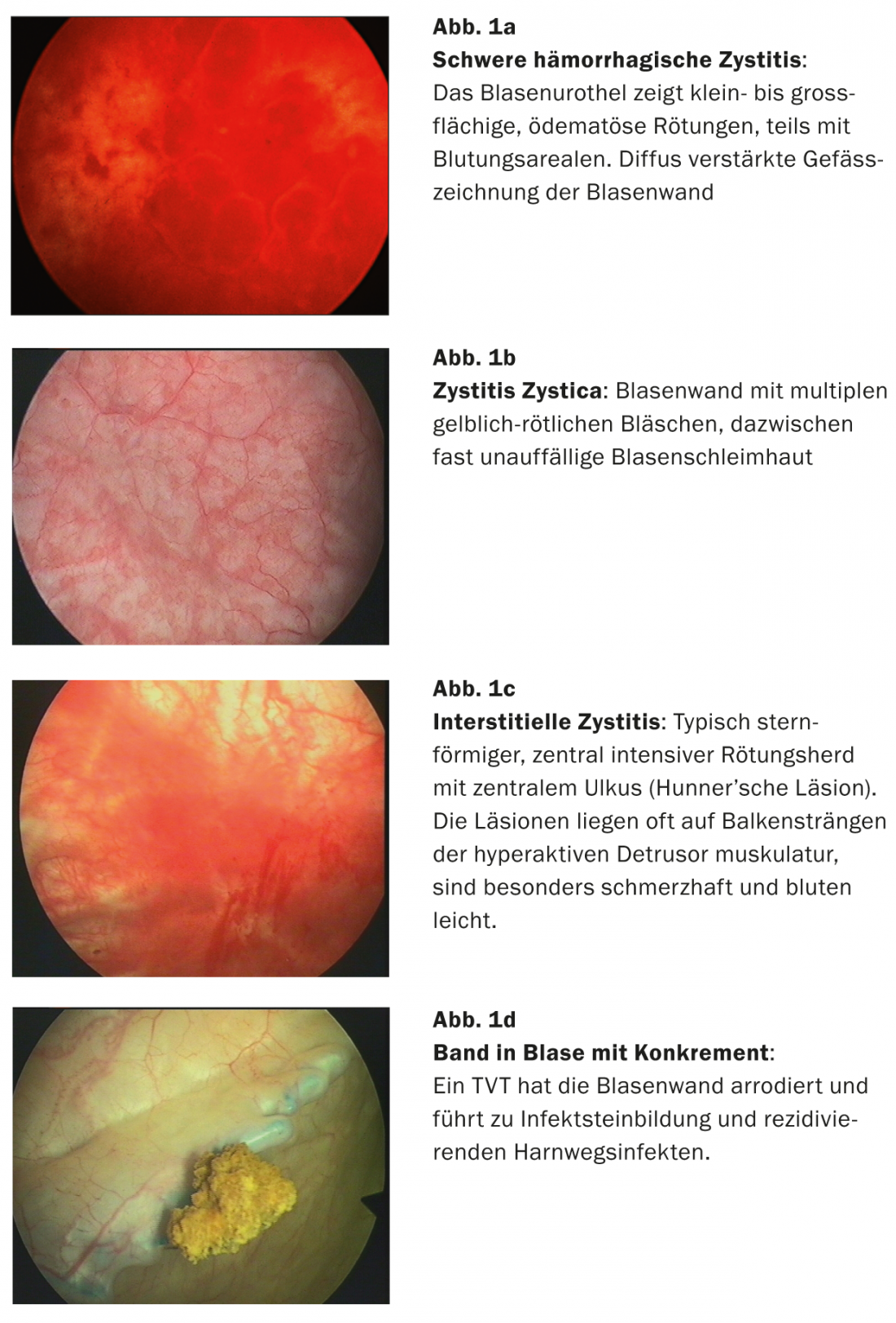

Cystoscopy (Fig. 1a-d) is obligatory to detect chronic inflammation on the bladder wall or to rule out other diagnoses that may cause inflammation-like symptoms, such as interstitial cystitis, but also dermatoses, tumors, and foreign bodies (e.g., perforation of a DVT band) [13].

Multimodal therapy concept

The treatment of recurrent cystitis is carried out according to our multimodal therapy concept, which has proven very successful in practice over the last 20 years.

First, the infection is sanitized in a targeted manner that is appropriate for resistance, and then we support the host and its defense mechanisms to reduce recurrence rates as much as possible and to achieve long-term improvement to complete healing of infections.

The key points are specific intimate care with pH-neutral wash lotions and the use of fat creams, in some cases also with those to which essential oils are added. In the case of very thin mucous membranes in peri-menopause or when using certain hormonal contraception, a local hormone cream is also indicated to build up the vaginal and bladder mucosa. If the amount drunk is insufficient, it must be increased with the aim of achieving at least two liters of urine over 24 hours.

Pentosan polysulfate, chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine sulfate help to build up the protective layer of the bladder wall, the so-called glycosaminoglycan layer (GAG layer).

The vaginal flora, which is usually disturbed by repeated antibiotic use or excessive washing behavior, can be built up and supported with vaginal products containing lactic acid as a supplement to hormone creams.

The immune defense is additionally stimulated by a vaccination against E. coli bacteria (Uro-Vaxom® vaccination). In the case of a frequently present chronic inflammation of the Schenke’s glands (extreme pressure dolence of the urethra on palpation or during intimate intercourse), a massage out with a pessary is necessary. The pessary is usually worn during the day, for a period of three months with the application of hormonal cream. As a rule, we do not use low-dose permanent prophylaxis with antibiotics or acidification of the urine in our therapies.

Summary

Urinary tract infections are among the most common female conditions. 40-50% of women are affected. Both the workup and treatment of recurrent urinary tract infections can be very challenging.Therefore, a great deal of experience, a high level of expertise, and close collaboration between specialists such as urogynecologists, nurse practitioners, and primary care physicians are required.

There are usually multiple causes that lead to recurrent urinary tract infections and chronic inflammatory conditions. The best treatment success is achieved when all causes of the disease are identified early and treated simultaneously. Even with simple measures, every woman herself can contribute a lot to the healing and prevention of this disease.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- Recurrent cystitis is becoming increasingly common.

- They meet young and old. Causes can be: predisposition, immune deficiency, lifestyle, sexual behavior, clothing, dry mucous membranes (pill/hormone deficiency in postmenopause), decline in immune defense with older age and multimorbidity.

- Recurrent cystitis cannot be cured with antibiotics alone.

- For healing and subsequently as long-term prophylaxis against recurrence, we need a multimodal approach.

- Successful therapies and long-term prophylaxis can usually be performed in the office.

- If this is not successful, we recommend extended clarification/therapy/consultation at a center specializing in this area.

Julia-Christina Münst, M.D.

Literature:

- Renard J, et al: Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2012; 119 (Suppl 3): 727.

- Foxman B: Am J Public Health 1990; 80: 331-333.

- Petersen EE: J Urol Urogynecol 2008; 15: 7-15.

- Savaria F, et al: Practice 2012; 101: 573-579.

- Hooton TM, et al: N Engl J Med 1996; 335: 468-474.

- www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/043-044.html

- Nicolle LE: Infect Dis Clin North Am 1997; 11: 647-662.

- Raz R, et al: Clin Infect Dis 2000; 30: 152-156.

- Eberhard J: Phytotherapy 2007; 1: 23-24.

- Casper F, Petri E: Int Urogynecol J 1999; 10: 171-176.

- www.uroweb.org/gls/pdf/18_Urological infections_LR.pdf

- Eberhard J, Viereck V: Hausarzt Praxis 2008; 7: 9-14.

- Viereck V, Eberhard J: J Urol Urogynecol 2008; 15: 37-42.

FAMILY DOCTOR PRACTICE 2013; (8)11: 28-34