How does the immune system change over a lifetime and what impact do such changes have on the development and treatment of multiple sclerosis? Answers to these and similar questions were given by Prof. Dr. med. Amit Bar-Or (USA) and Prof. Dr. med. Jiwon Oh (CAN) during a symposium.

“In the last 25 years, the therapy of multiple sclerosis has changed fundamentally,” said Prof. David Bates, MD (UK), chair of the symposium. “This has also improved the life expectancy of patients.” There are therefore more and more patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) at an older age, he said. In addition, the proportion of patients diagnosed with the disease at an age of more than 60 years is increasing. “At the other end of the age spectrum, more and more children are being diagnosed with acquired demyelinating diseases, including children with MS,” Prof. Bates continued. Finally, between the two age extremes lies a phase of life in which family planning also plays a central role for many patients. This is also important in the context of MS and its therapy.

Few treatment options for pediatric patients

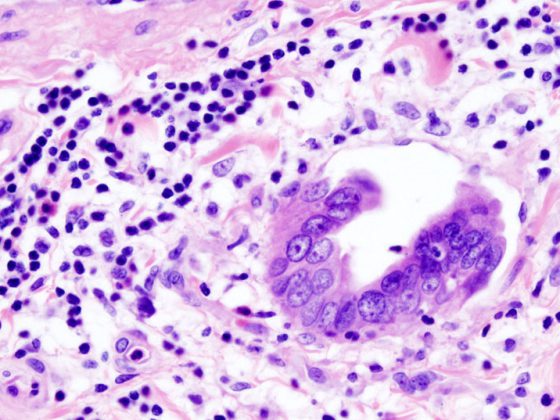

As Prof. Amit Bar-Or, MD (USA), further explained, the concept of the development of MS in adulthood assumes that the interaction of multiple genes and environmental factors over time results in a deficient regulation of the immune system in the periphery and a targeted immune response, leading to the changes typical of MS. “Although there may be an equal number of genes involved in the development of pediatric MS, the period of exposure to environmental factors is certainly shorter,” the speaker indicated. In addition, he said, it is a fundamental task of the immune system to respond to all kinds of influences. “However, this changes it. It can therefore be difficult to distinguish such physiological changes – which are not a potential therapeutic target – from pathological ones. Because of their age, children have even fewer such changes, which can facilitate research.” For example, studies have discovered that certain abnormal T-cell subpopulations are detectable in children with MS [1].

“If a child develops MS, it typically happens during puberty,” described Prof. Jiwon Oh, MD (CAN). As with adult patients, pediatric MS affects significantly more girls than boys, he said. If the relapse rate is high in the initial phase of the disease, this correlates with a poor prognosis [2,3]. “In the first decade of MS, pediatric patients rarely develop physical disability. However, in the longer term, irreversible disability occurs ten years earlier in these patients than in patients in whom the disease manifests in adulthood,” Prof. Oh added. “However, cognitive changes occur as early as the first year of disease and can progress rapidly if left untreated.” Therefore, the therapeutic goal in pediatric MS patients is to stop disease activity early [4]. However, therapy options for children hardly exist. Several disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), such as peginterferon beta-1a, dimethyl fumarate, teriflunomide, and also alemtuzumab, are currently being studied in pediatric patients.

Long-term effectiveness and safety is important

Early use of therapy is indicated not only in pediatric but also in adult MS patients, as the time between diagnosis and initiation of therapy has an impact on disease progression [5]. “If a highly effective therapy is chosen in this case, it may better control progression but may put the patient at higher risk for side effects,” Prof. Oh explained. Data on long-term use and safety are now available for several DMTs. Data presented at ECTRIMS included safety and efficacy data for dimethyl fumarate in relapsing-remitting MS over a 10-year treatment period [6]. Over this period, 73% of patients experienced no relapse or only one relapse. The adjusted annual thrust rate from years 0 to 10 is 0.107. At year 10, 79% of patients had an EDSS of ≤3.5. In 64% of patients, there had been no confirmed disability progression over the ten years. Moreover, no new or unexpected safety findings were observed over the entire period. Rates of serious infections and malignancies remained stable.

Life situation influences choice of therapy

The next part of the symposium focused on MS and pregnancy. It is known that there is a substantial reduction in the relapse rate during pregnancy [7]. On the one hand, this is explained by hormone-induced changes in the maternal immune system. On the other hand, fetal antigens interact directly with the maternal immune system and induce the production of regulatory T cells [7]. Regarding the choice of therapy in MS patients, Prof. Oh said, “The initial choice of a therapeutic agent is influenced, among other things, by whether or not pregnancy is planned soon. Besides that, the patient also needs to be informed about which therapeutic agents should have a washout period and how long it should last.” She also pointed out that there is currently insufficient data from prospective studies on the course of pregnancy for most of the available therapeutic agents. “Relatively extensive and also quite reassuring data from various registries are available to us on the older agents – the beta interferons and glatiramer acetate,” she said.

No guidelines for therapy of older MS patients

Finally, the symposium concluded with a discussion of older MS patients. One hypothesis is that age- and therapy-related changes in the immune system have a (super)additive effect in these patients, thereby accelerating the physiological processes of immunosenescence and inflammatory aging [8]. Data from a meta-analysis also support a lack of effect of DMTs in patients older than 53 years. “However, the results of a subgroup analysis of the pivotal dimethyl fumarate trials in relapsing-remitting MS showed a clear effect on several MRI parameters of disease activity even in patients over 40,” Prof. Oh advised. “Something similar was shown for peginterferon beta-1a in patients over 50, but the patient numbers here were relatively small.” As a procedure in daily practice, Prof. Oh recommended starting DMT in patients aged 55+ only when MS is obviously active (clinically and on MRI). “If a patient is over 55 or 60 and appears clinically stable on DMT, unfortunately there are no good guidelines on whether or not to continue therapy here.” It is also unclear how to proceed with a patient if the disability progresses even though there is no evidence of disease activity on imaging and there are no relapses, he said. “Personally, I make an individual decision here on a case-by-case basis,” Prof. Oh said.

Source: Symposium “From pediatric MS to immunosenescence – an interactive discussion.” 35th Congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, September 13, 2019, Stockholm/S.

Literature:

- Mexhitaj I et al. Abnormal effector and regulatory T cell subsets in paediatric-onset multiple sclerosis. Brain 2019; 142: 617-632.

- Chitnis T, et al: Trial of fingolimod versus interferon beta-1a in pediatric multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2018; 379: 1017-1027.

- Alroughani R, Boyko A: Pediatric multiple sclerosis: a review. BMC Neurol 2018; 18: 27.

- McGinley M, Rossman IT, et al: Bringing the HEET: The Argument for High-Efficacy Early Treatment for Pediatric-Onset Multiple Sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics 2017; 14: 985-998.

- Kavaliunas A, et al: Importance of early treatment initiation in the clinical course of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2017; 23: 1233-1240.

- Gold R, et al: Overall Safety and Efficacy Through 10 Years of Treatment With Delayed-release Dimethyl Fumarate in Patients With Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis. Ectrims 2019; Abstract P1397.

- Patas K, et al: Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis: feto-maternal immune cross talk and its implications for disease activity. J Reprod Immunol 2013; 97: 140-146.

- Schweitzer F, et al: Age and the risks of high-efficacy disease-modifying drugs in multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol 2019; 32: 305-312.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2020; 18(1): 38-39 (published 1/28/20, ahead of print).