Despite intensive research and great progress in identifying the manifestations of dementia, its underlying causes have yet to be explained. The Basel Dementia Forum 2017 provided an update of small steps and large research approaches.

The focus of current therapeutic research on Alzheimer’s disease is on identifying the disease before symptom onset: preclinical Alzheimer’s diagnosis should allow treatment to begin as early as possible. The main focus remains on amyloid-β, Prof. Reto W. Kressig, Felix Platter Hospital and University of Basel, summarized the known situation. Based on the research results available so far, it is still completely unclear whether the amyloid approach is of any use with regard to brain performance preservation.

The prolongation of quality of life is supported by the symptomatic therapy available today (see below). However, as the speakers at the event reflected in unison, preclinical Alzheimer’s diagnoses via biomarker changes are vulnerable after all, not only medically but also ethically: How will the patient react and what does this mean for his or her quality of life? How does the environment deal with such a diagnosis? Bergen preclinical diagnoses the risk of discrimination-to raise just a few questions [1].

In the area of symptomatic therapy, Kressig was unable to recommend anything new, but the data on ginkgo have caught up and, according to Kressig, represent an option along with cholinesterase inhibitors in early stages of dementia (keeping in mind the 1×240 mg/d dosage). The cholinesterase inhibitor dose (rivastigmine) can be increased again after six months at the earliest and combined with memantine if the MMSE value is <20 – according to his general recommendation. When asked whether starting therapy with a ginkgo preparation in the preclinical stage is advisable, Kressig referred to the GuidAge study, which showed that high-risk patients benefit from a long duration of treatment with ginkgo [2]. Compliance must be given, and for at least four years.

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) Scores

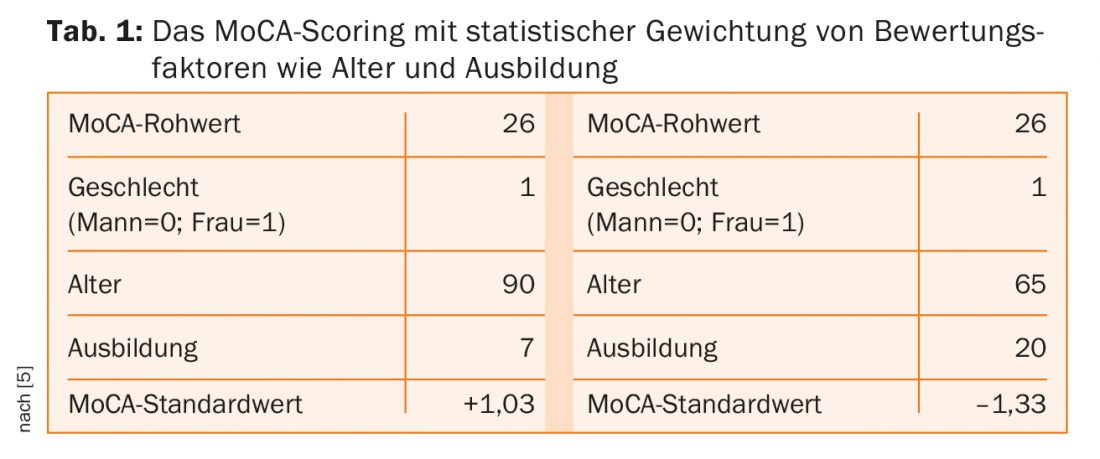

In his lecture, Prof. Andreas U. Monsch, Memory Clinc, Felix Platter Spital, Basel, went into more detail on early detection and scoring. In the journal Hausarzt Praxis, Monsch et al. already presented the tools “BrainCheck” and “BrainCoach” in detail [3]. Current research is dedicated to the assessment method “Montreal Cognitive Assessment” (MoCA), which is supposed to provide more precise results than conventional testing methods. The threshold for mild neurocognitive impairment is 25/26 according to the MoCA standard [4]. In a norming study of 283 demonstrably healthy individuals conducted by the Memory Clinic with other German-speaking universities, the healthy individuals scored on average three points lower on the MoCA compared with the MMSE [5]. The healthy individuals tested had a score of at least 27 on the MMSE and at least 85 on the CERAD-NAB Total Score (CERAD-NAB = The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease Neuropsychological Assessment Battery). Of concern is that, as a result, nearly one-third of the individuals tested were below the official MoCA threshold. Based on these results, Prof. Berres, Koblenz University of Applied Sciences, statistically incorporated age, education and gender into the evaluation. The practical effects are exemplified by table 1: A 90-year-old woman with seven years of education and a raw MoCA value of 26 comes to a standard statistical MoCA value of +1.03. A 65-year-old woman with 20 years of education and also a raw MoCA value of 26 comes to a value of -1.33 – i.e. pathological.

It is planned in the further course of the project to provide evaluation tables showing in which range of results a status can be assessed. For example, it is clear that for the 65-year-old woman with 20 years of education, a MoCA value of 26 is just below the value she should achieve, while the 90-year-old woman with a MoCA value of 20 can still be classified as healthy.

Outlook: After validating the study of the MoCA test at the Memory Clinic, the goal is to move forward with subscore analysis to identify specific patterns. Publication is planned on a website www.mocatest.ch.

Dementia and neuroimaging

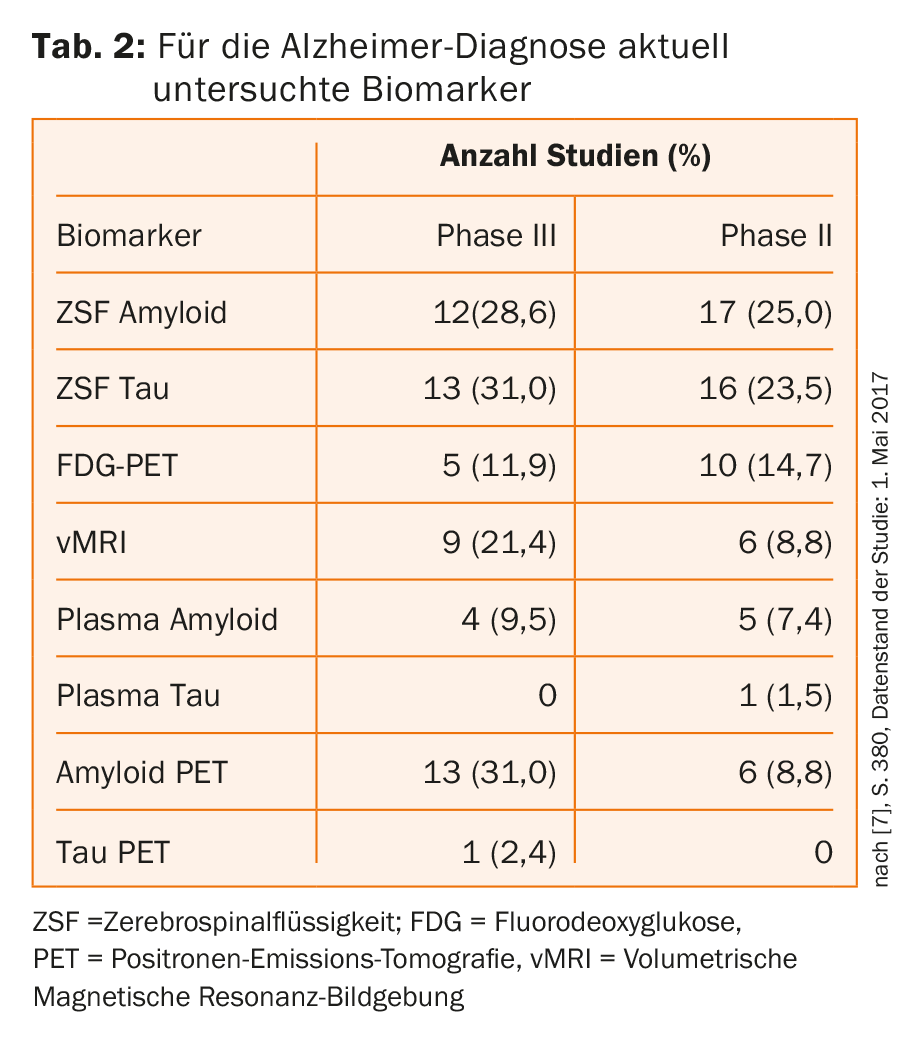

PD Paul G. Unschuld, MD, Zurich, Switzerland, underscored the role of imaging in current dementia research. In Alzheimer’s disease, the focus is on two pathological hallmarks: the extracellular accumulation of amyloid-β in the form of plaques, which can be detected decades before the first symptoms appear, and the intracellular accumulation of pathological tau in neurofibrils, which correlates with neurogeneration – in affected individuals, a clear loss of brain tissue is then visible. Table 2 provides an overview of biomarkers relevant to AD diagnosis derived by Jeffrey Cunnings from global clinical trials registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov database [6]. Of these eight markers, four are detectable via imaging techniques.

There are nuclear and non-nuclear biomarkers: the latter include vMRI (=volumetric magnetic resonance imaging), which can be used to detect loss of volume as a result of neurodegeneration. Nuclear medicine procedures include, for example, FDG (=fluorodeoxyglucose)-PET (=positron emission tomography), which allows conclusions to be drawn about synaptic integrity and identifies specific disease patterns with computer-assisted evaluation, or the detection of amyloid-β and hyper-phosphorylated tau using suitable PET tracers.

A new area of application of imaging techniques is the study and exploration of novel pathophysiological processes that could lead to dementia; an example of this is the study of the accumulation of iron in the aging brain [7].

It is possible that technologies will become increasingly available in the future that will allow inferences to be made about local metabolic changes associated with memory loss in the elderly. One such technique is Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopic Imaging (MRSI), which allows tissue-specific measurement of glutamate, N-acetylaspartate, and also GABA and myoInsoitol [8].

Another new technique is the correction in real time of physiological field disturbances caused, for example, by breathing, movement, heartbeat of the examined patient. This technique makes it possible to study the brain with particularly high spatial resolution, and in this way to further investigate the significance of the earliest changes.

Source: 6th Basel Dementia Forum, November 16, 2017

Speakers: Prof. Dr. med. Reto W. Kressig, Prof. Dr. phil. Andreas U. Monsch, PD Dr. med. Paul G. Innocence

Literature:

- Karlawish J: Addressing the ethical, policy, and social challenges of preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurology, 2011, 77(15); 1487-1493.

- Gschwind YJ, Bridenbaugh SA, Reinhard S, Granacher U, Monsch AU, Kressig RW: Ginkgo biloba special extract LI 1370 improves dual-task walking in patients with MCI: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled exploratory study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2017 Aug; 29(4): 609-619.

- Monsch AU, Ehrensperger MM, Thomann A: BrainCheck and BrainCoach in family practice, in: HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 2 (12): 8-12.

- Nasreddine ZS, et al: Normative data for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in a population-based sample. Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53(4): 695-699.

- Thomann A, et al: data on file

- Cummings J, Lee G, et al: Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2017. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 2017; 3: 367-384.

- Van Bergern JM, Li X, Hua J, Schreiner SJ, Unschuld PG, et al: Colocalization of cerebral iron with amyloid beta in mild cognitive impairment. Scientific reports, 2016; 6: 35514.

- Schreiner SJ, Kirchner T, Wyss M, Van Bergen JMG, Michels L, Gietl AF, Unschuld PG, et al: Low episodic memory performance in cognitively normal elderly subjects is associated with increased posterior cingulate gray matter N-acetylaspartate: a (1)H MRSI study at 7 Tesla. Neurobiol Aging. 2016 Dec; 48: 195-203.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2018; 16(1): 42-45.