Cancer in childhood and adolescence places special demands on both those affected and the physicians treating them. Specialized, interdisciplinary centers therefore work closely in defined infrastructures to ensure the survival of young patients. Thanks to worldwide research, optimized therapeutic approaches and effective measures, this is also working better and better.

Malignancies in children are rare. In Switzerland, approximately 215 new cases are diagnosed annually [1]. The chances of cure have also improved significantly in recent years. Yet cancer is the second leading cause of death in children. However, childhood cancers cannot be compared to adult malignancies. While carcinomas account for >90% of new cases in adults, they are extremely rare in children (<1.5%). Therefore, findings from adult oncology cannot be transferred 1:1 to pediatric oncology [2].

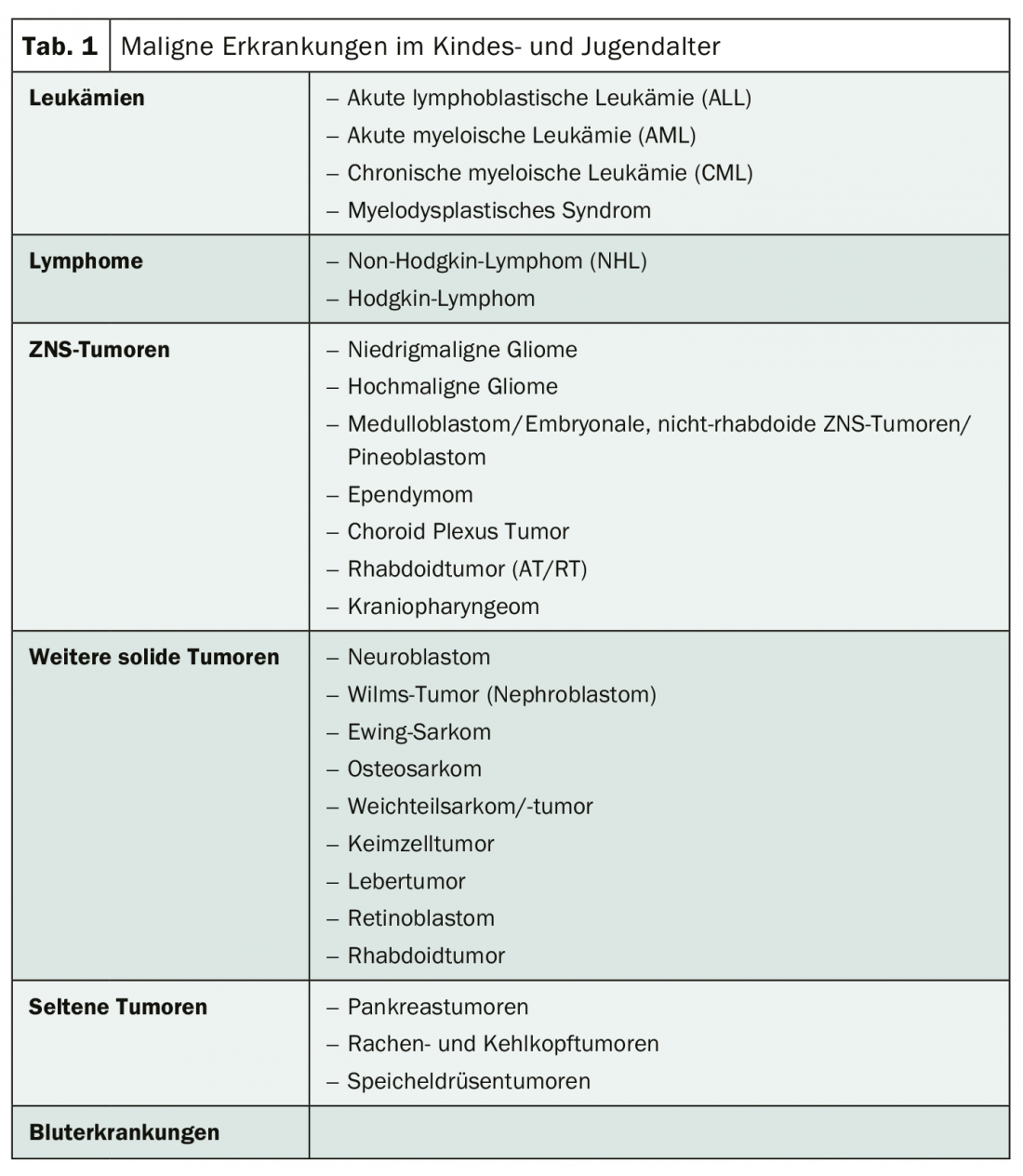

In children, the main incidence is leukemia at about 33%, followed by tumors of the central nervous system at about 24% and lymphoma at about 11%. In addition, there is neuroblastoma (approximately 7%) and nephroblastoma (5%) (Table 1) [3,4]. While embryonal tumors are most common in infancy, bone tumors are most common in adolescents and young adults. Malignant diseases at a young age have some peculiarities:

- they are very rare,

- biologically, these are diseases that can usually be treated curatively,

- the genetic complexity is comparatively low,

- the cure rate is >80%.

Diagnostics in experienced hands

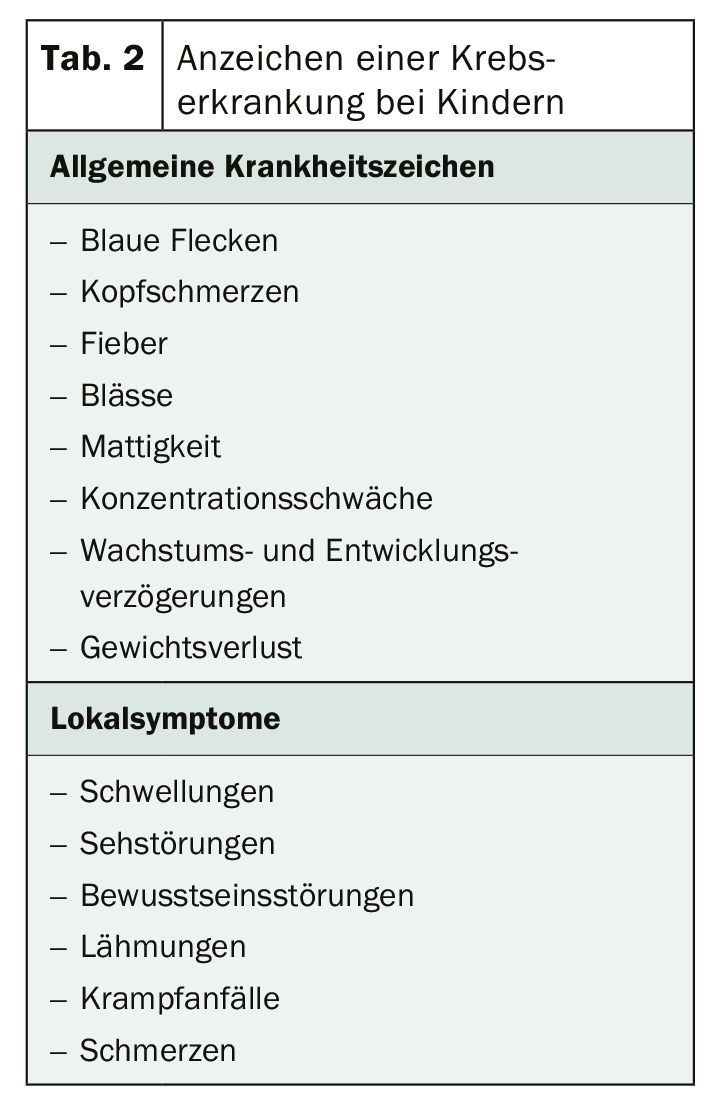

Detecting cancer early is extremely difficult. Because the signs are rather harmless at first. However, if rather nonspecific symptoms persist, malignant disease should be excluded (Table 2) [5]. In children, unlike adults, staging examinations are often performed on an inpatient basis. In principle, however, diagnostics is carried out according to the same principles and methods. The more precisely the examination procedures are selected, the more efficiently the diagnosis can be made. Therefore, the pediatric oncologist plans not only referrals to specialized diagnosticians, but also the sequence of necessary interventions. Especially if these have to be done under sedation. In the best interest of the child, anesthesia should be minimized.

Many therapeutic strategies are guided by staging results, which is why this assessment in particular is crucial. Nephroblastomas, for example, are not primarily operated on after radiological diagnosis, but chemotherapied without histological diagnosis confirmation [2]. Brain tumors, on the other hand, are removed surgically if possible. Because incomplete diagnosis may result in incorrect treatment and thus prevent reliable assessment of treatment response, initial assessment is of particular importance in pediatric oncology.

Effective treatment concepts

Oncological therapy in children is basically multimodal and risk-adapted. Chemotherapy, in particular, has a high priority because the diseases usually grow rapidly and metastasize early. In this case, a neoadjuvant approach, i.e., the combination of intensive polychemotherapy and local surgical and/or radiotherapeutic measures, is preferable. Nearly all pediatric oncologic diseases respond to treatment with cytostatic agents. The right time for surgery depends on the diagnosis. Complex molecular studies on risk adaptation are indispensable for this. Radiation therapy is used as a component of multimodality treatment for both curative and palliative purposes. Indications and definitions of the region to be irradiated as well as the dosages and fractionations are coordinated for the different tumor types, taking into account the other therapy modalities, the age of the patients and histological criteria. But there are limits to this 3-pillar therapy. It has been largely exhausted. Therefore, new approaches are also being taken in pediatric oncology with molecular and immunotherapy.

The aim of the new approach is to attack tumor cells as specifically and effectively as possible, even in children, without inducing concomitant toxicities. For this purpose, chemotherapy is combined with the administration of antibodies or CAR-T cells, for example. Checkpoint inhibitors may also be a way to further increase cure rates in children.

Since these procedures affect tumor growth and the interaction between the immune system and the tumor in different ways, effective combinations could also be promising with regard to recurrence prophylaxis. However, only the future will tell if and how they can be integrated into current treatment protocols [2,6,7].

Literature:

- www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/gesundheit/gesundheitszustand/krankheiten/krebs/bei-kindern.html (last accessed 05.06.2020)

- Eggert A: Pediatric oncology – an overview. Oncology Today 2016; 7: 48-54.

- www.kinderkrebsinfo.de/erkrankungen/index_ger.html (last accessed 05.06.2020)

- www.krebsgesellschaft.de/onko-internetportal/basis-informationen-krebs/leben-mit-krebs/beratung-und-hilfe/kinderonkologie-was-hilft-kindern-mit-krebs-und.html (last accessed 05.06.2020)

- www.kinderkrebsinfo.de/patienten/fragen_zu_krebs/was_sind_die_zeichen_einer_krebserkrankung/index_ger.html (last accessed 05.06.2020)

- www.kinderkrebsinfo.de/patienten/forschung/neue_therapien/immuntherapie/index_ger.html (last accessed 05.06.2020)

- von der Weid N: Immunotherapies in pediatric oncology. SZO 2018; 4: 27-30.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2020; 8(3): 34-35.