In cardiology, MINOCA defined a new infarct subtype that is still frequently overlooked in clinical practice. However, the prognostic relevance cannot be dismissed.

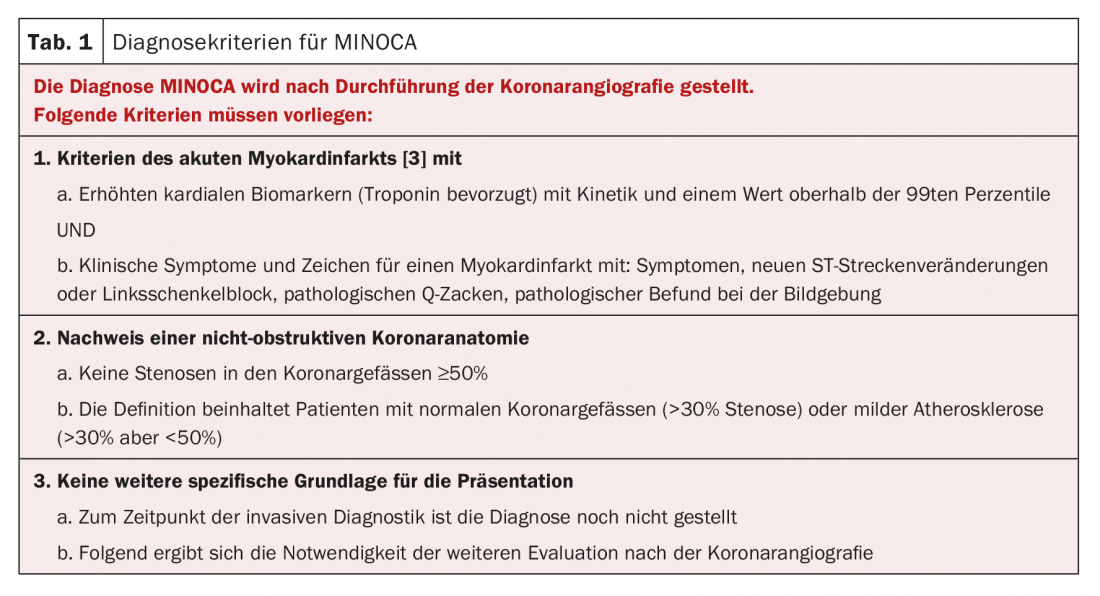

The diagnosis of Myocardial Infarction with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries (MINOCA) is based on evidence of irrelevant flow limitation of coronary vessels and clinical evidence of acute myocardial infarction [1,2]. The diagnosis is made after evaluation of the patient’s clinical presentation and invasive diagnosis by coronary angiography in the patient [1]. For the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction, the combination of typical clinic and positive cardiac biomarker findings must be present [3]. Therefore, in the absence of appropriate differential diagnoses, the entity of MINOCA must be assumed in these clinical situations. The basis for the establishment of this disease pattern in clinical medicine is mainly due to the following points:

- Provide a nomenclature for this group of clinically abnormal patients.

- Need for further clarification of causes in these patients

- Presenting the need for further studies to investigate mechanism, clinical outcome, and management in the future.

MINOCA diagnostic criteria are presented in Table 1 .

Signs of acute myocardial infarction in MINOCA.

With the updated fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction [3], there is still a need to combine clinical symptoms with cardiac biomarkers to make the diagnosis. In addition, the clinical syndrome of MINOCA is discussed. The biomarkers used in this context should also be highly sensitive troponins [3]. For diagnosis, the distinction between type 1 myocardial infarction, which represents the occlusion of a coronary vessel by a thrombus, and type 2 myocardial infarction, which is defined as a supply mismatch of coronary vessels including coronary spasm, is important. One issue with using the revised definition is the focus on troponin. In this context, the following considerations must be kept in mind:

- Troponin is organ-specific but not specific for a single disease

- Analytical procedures are rarely the cause of noncorrect troponin measurements

- Differential diagnoses must be considered and excluded accordingly

Table 2 shows an overview of potential diseases that may be associated with troponin elevation [1,3].

Angiographic criteria

The criteria for the diagnosis of MINOCA require coronary vessel stenosis in the invasive diagnosis of <50% [1,4]. Partial visualization of normal coronary anatomy without stenosis was required. However, this was discarded because of invasive imaging and the possible presence of significant atherosclerotic changes [1,4]. Use of the definition based on normal coronary anatomy is limited primarily by the following:

- Intracoronary imaging is often not used during invasive diagnostics

- Coronary spasm may occur regardless of the presence of coronary lesions

- The changes may be described only incidentally in other diseases, for example, when myocarditis or pulmonary embolism are present as disease [1].

Therefore, for the definition of MINOCA, the exclusion of a relevant stenosis should be described rather than the absence of any change in the coronary vessels [1]. Despite the limitations described above, a distinction between patients with normal coronary anatomy and patients with changes in the sense of stenosis <50% could be relevant from the research point of view. In this context, it is important to reiterate the importance of the clinical situation of the patient and the use of the definition MINOCA as a working hypothesis until the final diagnosis. Patients presenting with clinical history, symptomatology, laboratory constellation of myocarditis and receiving invasive exclusion of coronary artery disease should be managed under the diagnosis of “suspected myocarditis” and not “MINOCA”.

Clinical characteristics

Patients diagnosed with MINOCA tend to be younger than patients with obstructive coronary artery disease and often have a different distribution in terms of patient sex [1]. In coronary heart disease, men are most affected at young and middle age, although no clear clustering in either sex has been described in MINOCA. Here, a gender-specific cause can be assumed in connection with the different hormonal status of the patients [1]. In this context, it must be reiterated that patients with MINOCA may present with ST-segment elevations on the ECG as well as without them.

Prognostic relevance in recent studies

In a recent study that included 4793 patients based on ST elevation on ECG and clinic of myocardial infarction between 2009-2014, it was shown that of these patients, 88% had obstructive coronary artery disease, but the remaining 12% had either no stenosis or stenosis of <50% [5]. Results were presented for short-term follow-up of up to 30 days, in which patients with no or no relevant coronary artery stenosis had better survival than those with obstruction. When survival in the two groups was considered after the first 30 days, survival of patients with nonobstructive cardiovascular disease was similar to that of patients with obstructive cardiovascular disease. Patients with normal coronary vessels had significantly more limited survival [5]. Follow-up >30 days in patients without relevant obstruction showed a significantly lower rate of cardiovascular causes of death with 21% and 29% for the patients with non-obstructive coronary artery disease and the patients with normal coronary vessels, respectively [5]. The reason for the limited survival of patients without obstructive coronary artery disease was mainly the presence of relevant diseases, such as underlying malignancies, which explained the poor prognosis. The authors’ conclusion from these results was that patients with a referral diagnosis of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and exclusion of obstructive coronary artery disease were considered to have only mild disease and thus were discharged from the hospital early, with no further workup [5].

Clinical assessment

During the acute presentation of the patient, the performance of echocardiography or levocardiography can be an important tool in the diagnosis of Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy [1]. Intracardiac imaging can also be performed as part of the catheter examination, although this is not currently the standard and is therefore not established everywhere. As the disease progresses, additional imaging techniques provide important tools for more accurate clarification. Here, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is of particular importance, as the measurement of late-gadolinium enhancement allows differentiation into the various disease patterns based on the pattern of enhancement of this contrast agent [1]. Within the clinical symptom complex, subendocardial enhancement may suggest ischemia as a differential diagnosis to MINOCA, and subepicardial enhancement may be indicative of cardiomyopathy [1]. Another diagnostic imaging modality that is particularly useful for young patients without cardiovascular risk factors is cardiac computed tomography as a complementary diagnostic modality or to detect pulmonary artery embolism or aortic pathology.

Causes and triggering factors

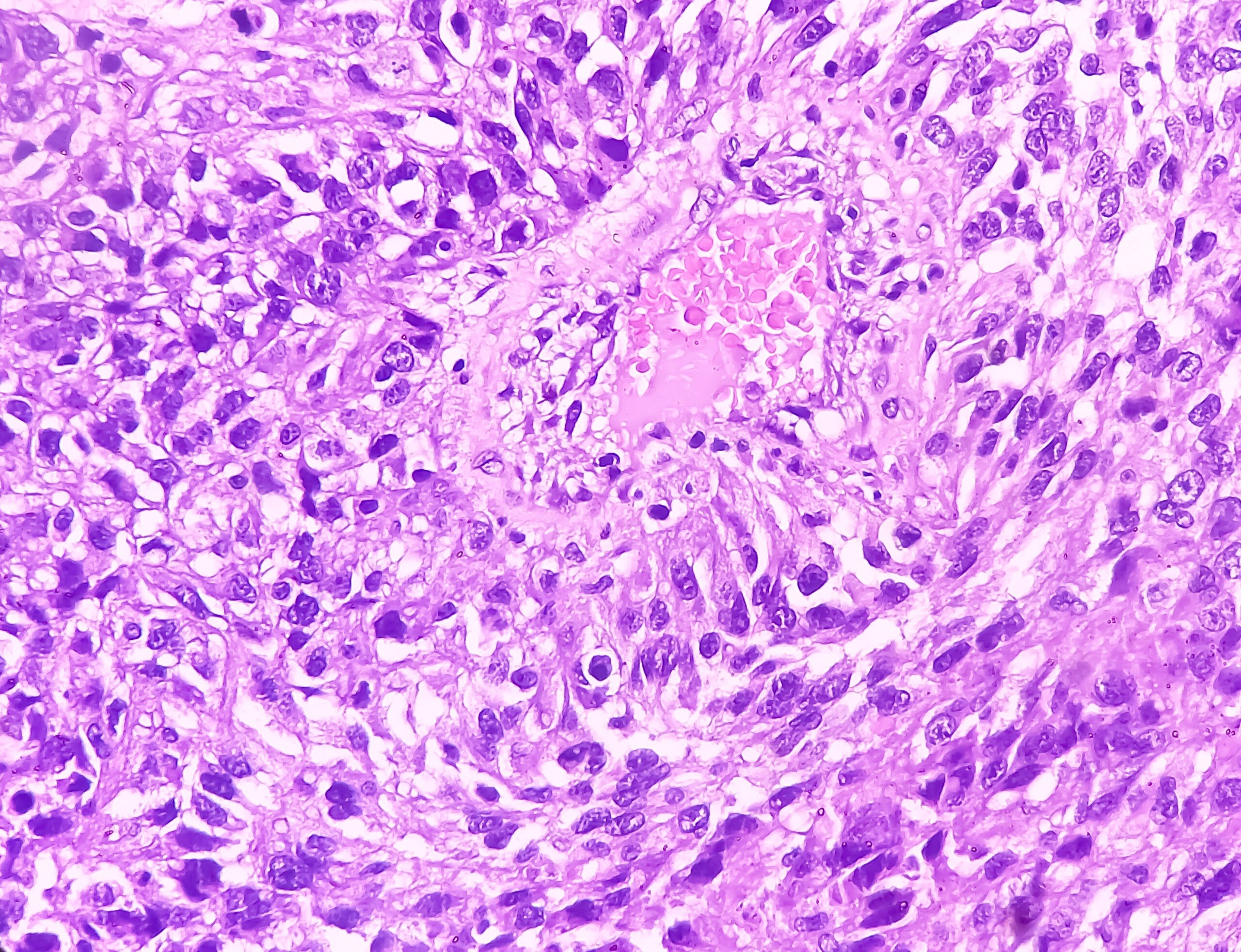

A Unstable atherosclerotic plaque is often the cause of MINOCA and is grouped under the definition of type 1 myocardial infarction according to the universal definition of myocardial infarction [1,3]. In the text document of the universal definition of myocardial infarction, 5-20% of all type 1 infarctions are classified as MINOCA. These patients show unstable plaque in the vasculature on intravascular ultrasound imaging in up to 40% of cases [1,3]. Intracoronary imaging has a high value in patients without obstructive coronary artery disease for further clarification and assignment to a disease pattern [4].

Pathophysiologically, coronary artery spasm is often associated with MINOCA disease [1,6]. This disease pattern represents hyperactivity of vascular smooth muscle to endogenous vasoactive mediators, although exogenous substances, such as methamphetamines and cocaine, can also lead to spasm of coronary vessels and thus MINOCA [1,6]. If myocardial infarction without obstruction is suspected, vasoactive testing should be considered because this patient group in particular often has a positive result [1,6] and coronary testing can simultaneously provide an indication for drug treatment with calcium channel blockers or long-acting nitrates [4,7,8]. Patients with MINOCA should be assumed to have a vasospastic component especially if they respond well to nitrates when they have symptoms, have passive ECG changes, and the pain episodes occur primarily at night [1].

In patients with MINOCA, coronary artery embolism may also be the cause of the symptoms. Especially when patients have thrombophilia or other conditions that may be associated with an increased tendency to clot, such as atrial fibrillation or valvular heart disease such as mitral valve stenosis [1]. Overall, however, this condition is generally rarely described as a cause, but this is partly due to the lack of screening for this cause complex [1].

Spontaneous dissection of a coronary vessel often causes acute myocardial infarction during its course. Although coronary vessels can be diagnosed with no visualizable occlusions during initial catheterization, coronary imaging is essential when suspected. Overall, spontaneous coronary dissections occur more frequently in women, and in this case in particular, the appropriate diagnosis should be made during coronary angiography [1]. Overall, approximately 90% of patients are women and there is a higher association with pregnancy. Overall, spontaneous dissection of a coronary artery should be considered, especially in low-risk patients because of young age and the absence of risk factors [1,9].

Important differential diagnosis

The clinical picture of Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy often presents as an acute coronary syndrome with ST-segment changes on ECG and comes to the fore clinically mainly as acute heart failure with the exclusion of stenosing heart disease [1]. In general, the prognosis is not considered limited. However, mainly severe complications in the acute phase have been described. Furthermore, the occurrence of Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy has also been described in patients with underlying malignancies, and further screening is therefore recommended [1,10]. The revised Mayo criteria are used for the diagnosis of Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy:

- Midregional wall motion abnormalities with/or without apical involvement on ventriculography/echocardiography.

- Exclusion of coronary artery disease or acute occlusion of a vessel

- New ST-segment changes in the ECG

- Exclusion of pheochromocytoma or myocarditis.

New disease picture with a view to the future

MINOCA disease pattern is common in patients with acute coronary syndrome with a prevalence of 6-12%. The diagnosis is rarely made because it is a diagnosis of exclusion. However, it is of prognostic relevance. Recent studies have shown that patients with ST-segment elevation and exclusion of coronary artery disease had a significantly worse prognosis than patients with acute myocardial infarction, and this was mainly due to noncardiac disease. Diagnostics are multifaceted and primarily include cardiac catheterization and other imaging modalities, such as cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Due to the difficulty of diagnosis, this disease pattern is still rarely described in the literature and requires further prospective studies. An overview of the differentiated procedure for suspected MINOCA is provided in Figure 1.

Take-Home Messages

- The disease pattern MINOCA occurs frequently with a prevalence of 6-12%. A prerequisite is the exclusion of potential diseases associated with the clinical symptoms and diagnostic criteria of MINOCA.

- Typically, patients present with symptoms consistent with acute myocardial infarction and positive detection of cardiac biomarkers (clinically striking especially troponin with respect to dynamics).

- The basic diagnostic procedure is an invasive diagnosis by coronary angiography, which should be followed by a provocation procedure if suspected, or by taking biopsies depending on clinical necessity.

- Imaging techniques such as MRI and/or CT may be clinically helpful to rule out important differential diagnoses such as myocarditis, pulmonary artery embolism, or aortic dissection.

- Further diagnostics should be performed especially in the patients with ST-segment changes and exclusion of coronary artery disease. These patients have a significantly worse prognosis, which is mainly due to malignant diseases.

Literature:

- Agewall S, et al: ESC working group position paper on myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries. Eur Heart J, 2017; 38(3): 143-153.

- Thielmann M, et al: ESC Joint Working Groups on Cardiovascular Surgery and the Cellular Biology of the Heart Position Paper: Perioperative myocardial injury and infarction in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Eur Heart J, 2017; 38(31): 2392-2407.

- Thygesen K, et al: Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). J Am Coll Cardiol, 2018; 72(18):2231-2264.

- Radico F, et al: Angina pectoris and myocardial ischemia in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease: practical considerations for diagnostic tests. JACC Cardiovasc Interv, 2014; 7(5):453-463.

- Andersson HB, et al: Long-term survival and causes of death in patients with ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome without obstructive coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J, 2018; 39(2): 102-110.

- Marinescu MA, et al: Coronary microvascular dysfunction, microvascular angina, and treatment strategies. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging, 2015; 8(2): 210-220.

- Pepine CJ, et al: Coronary microvascular reactivity to adenosine predicts adverse outcome in women evaluated for suspected ischemia results from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute WISE (Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation) study. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2010; 55(25): 2825-2832.

- Flammer AJ, et al: The assessment of endothelial function: from research into clinical practice. Circulation, 2012. 126(6): 753-767.

- Adlam D, et al: European Society of Cardiology, acute cardiovascular care association, SCAD study group: a position paper on spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Eur Heart J, 2018. 39(36): 3353-3368.

- Sinning C, et al: Tako-Tsubo syndrome: dying of a broken heart? Clin Res Cardiol, 2010. 99(12): 771-780.

CARDIOVASC 2019; 18(1): 28-31