In many areas, adolescence is about a transition from decisions made by adults, which must be supported and accepted by the children, to self-responsible decisions by the adolescents, which must be supported and accepted by the parents and with whose consequences they then start their adult life. Especially for people with ADHD.

During adolescence, most families experience new discussions and conflicts in terms of content. It’s no longer about brushing your teeth or packing your school bag. Rather, it is a matter of renegotiating areas of responsibility and degrees of freedom, as well as the nature of communication between the “soon-to-be-adults” and the “already-adults,” which must prove itself in adolescence and beyond. In many areas, there is a transition from decisions made by adults, which must be supported and accepted by the children, to self-responsible decisions made by the young people, which must be supported and accepted by their parents and with whose consequences they then start their adult life. This is true for all families, but under special circumstances for families who have one or more children with an ADHD diagnosis in adolescence.

Changing symptomatology in adolescence

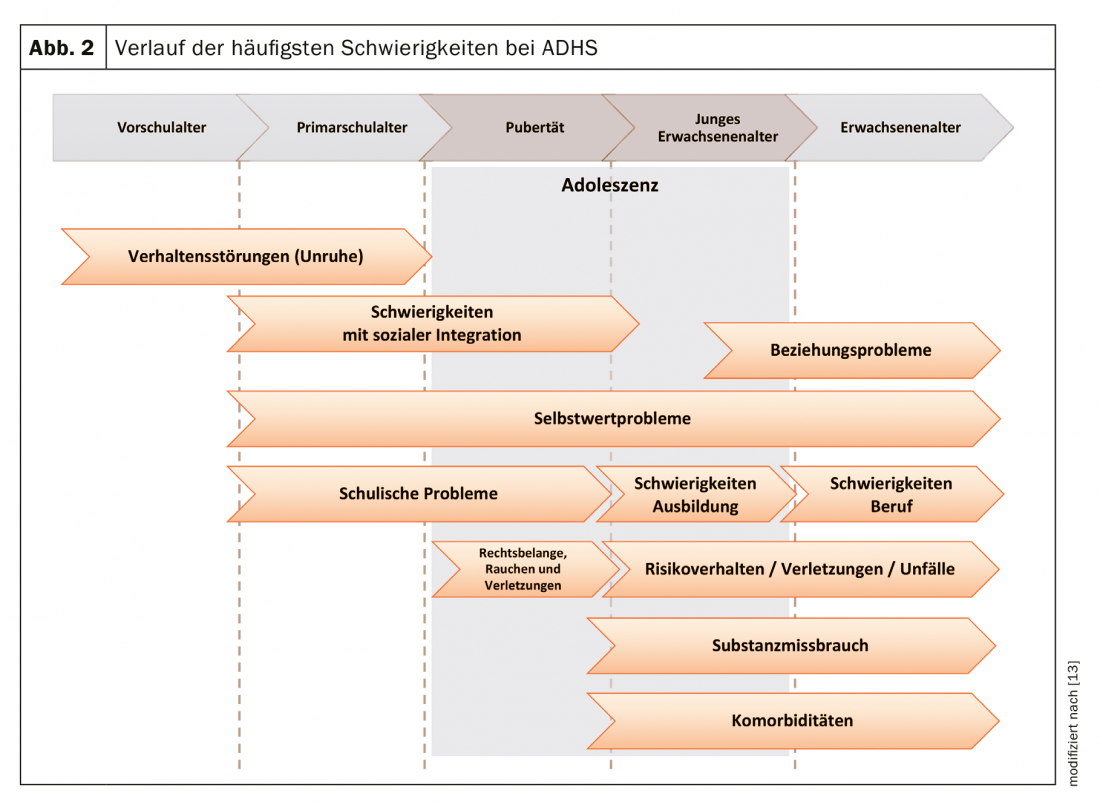

ADHD is not a “childhood disease” nor does it “just grow out of it” [1,2]. Clinically, the core symptomatology changes during the years of adolescence (Fig. 1). It has been recognized for about 15 years that symptoms do not simply reduce with puberty, but that different courses are possible. In adulthood, the full syndrome may persist, partial remission or residual remission may occur, or positive symptom development may be observed. In most courses, hyperactivity increasingly recedes into the background and attention deficit disorder comes to the fore with increasing age. Impulsivity may – but need not – persist. There are numerous publications on long-term clinical courses and also on the development of psychological comorbidities such as the increase in affective disorders, addictive disorders and personality disorders, especially in untreated ADHD.

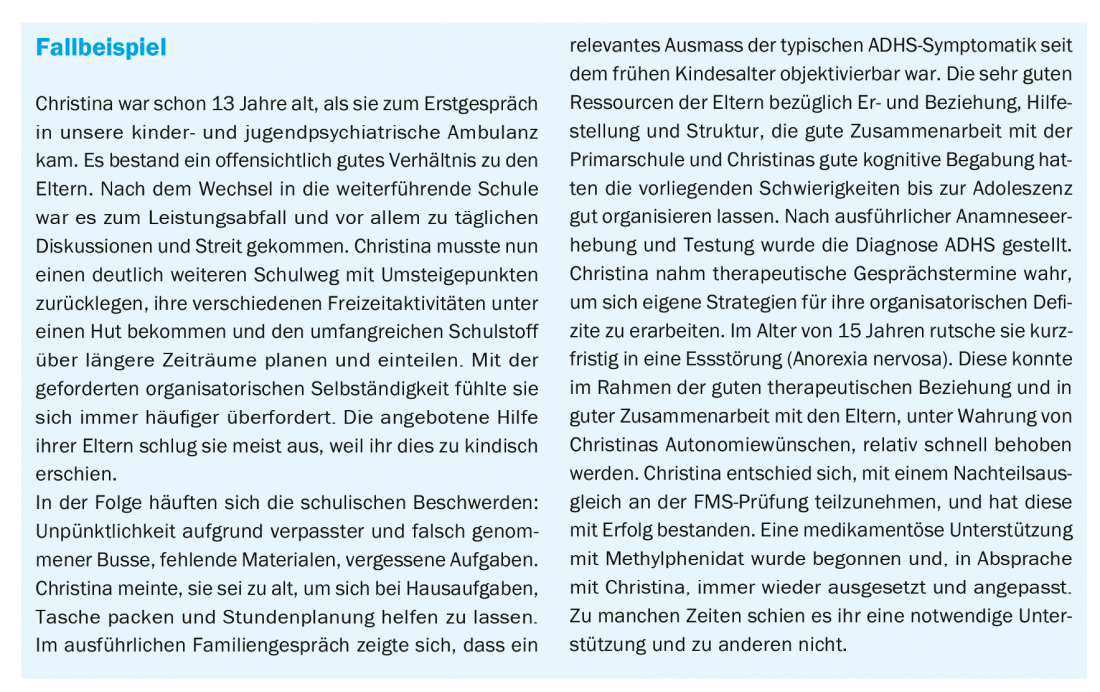

Even if the symptomatology can usually be attenuated and/or better compensated, there are (also) very specific findings of adolescents affected by ADHD. As the case study shows, there are always well-compensated attention disorders that do not lead to an initial diagnosis until adolescence. In these cases, the anamnesis shows that the symptoms already existed in childhood, but did not require treatment due to favorable constellations.

Adolescents with ADHD, compared to unaffected adolescents, showed simpler learning strategies on the one hand, and increased exploratory, i.e., curious, behavior on the other, in decision-making tasks. This means that they do not necessarily learn from experience (e.g., positive feedback does not necessarily lead to repetition of the behavior), but individuals still keep trying new ways of doing things [3]. In a creative profession this may be an advantage, but in school this pattern is usually not desired. Even healthy adolescents show peculiarities in decision making compared to children and adults. Thus, according to our study, including functional imaging, they are particularly sensitive to negative feedback and thus take our interpretation of this feedback particularly to heart [4]. It can now be summarized that adolescents affected by ADHD particularly often receive such negative feedback and a negative cycle develops.

Peculiarities of the parent-child relationship in adolescents with ADHD.

From the parents’ point of view, adolescence and the autonomy demanded of young people mark the beginning of a period of advances in trust and thus of discussions about the extent, appropriate timing and consequences of the new freedoms. For the most part, this has a “train-by-train” effect: manageable freedoms are granted, the associated expectations are met, and confidence in the young person’s independence grows. For example, when negotiating the time and framework of the way home after the exit. If the agreement is reliably adhered to, the level of trust usually increases in the following discussions. This principle works analogously in the areas of school independence, choice of friends, organization of room rules. The degrees of freedom increase with increasing reliability for both sides.

For parents of children with ADHD, developments are often less straightforward or successful, disrupting trusting relationships with adolescents and fueling parents’ and caregivers’ concerns about a successful start to adulthood. The ADHD-typical inattention and difficulties in impulse control easily lead to missing the bus or rashly accepting a spontaneous invitation, and subsequently to unreliability with the newly acquired freedoms. This happens to almost all adolescents, but to adolescents with ADHD much more frequently and persistently, putting more strain on the parent-child relationship.

Desire for autonomy vs. necessary structure

Young people are searching for a suitable identity, want and need to question values and relationships. Peer influences are gaining weight. Having a diagnosis that is linked to everyday difficulties may not seem like a useful identity building block at first glance.

The adolescents with ADHD experience more frequent failures and resulting self-doubt due to the symptomatology, despite good intentions. The development of a healthy self-confidence is therefore more at risk [1]. More often than their peers, they feel that they are not understood and treated unfairly; it is not uncommon for them to feel that their efforts are not valued or worthwhile.

During adolescence, a new ambivalence emerges between autonomy desires and the amount of structural and organizational support needed, e.g., in school matters. The expected independence in the areas of self-organization, action planning and time management increases with secondary school and often leads to excessive demands despite good talent. The impairments exist mainly due to the disorders in executive functions [5]. Their importance increases during adolescence, as parents become less representative and the tasks to be accomplished become more complex. The young people have to plan and structure their daily routines with school courses and leisure activities in various locations, choose and complete vocational training, reliably manage their money matters – all of which their parents usually (also) had in mind beforehand.

Figure 2 shows the particular difficulties over time.

Basically, these are the same issues and questions as in all families with adolescents. However, the extent and persistence of conflicts are usually much higher in adolescents with ADHD, and the possibilities for compensation are fewer. Patience and confidence are even more required in the affected families. Parents are tested countless times in the confidence of guiding a teenager who will be successful in the future professionally/scholastically and personally. Individual authors describe that (recreational) sport and exercise (in groups) as an important, promising and cost-effective component in the treatment of ADHD has received too little attention so far [6].

ADHD and career choice

Finding a suitable career is a challenge for everyone involved. It should individually fit the talents and interests of the young people and correspond to the cognitive potential. However, it should also provide a professional environment that is supportive and able to compensate for disruptions. Of course, there are no “ADHD professions.” To avoid failure, a realistic assessment of strengths and opportunities should be made together. Important questions are:

- Is the activity varied and involves movement?

- Can the individual tasks be divided into manageable stages in terms of time and content?

- Can the young person contribute his or her own creative ideas?

- Are there sufficient extrinsic motivational aids in the form of praise and feedback?

Even before the young people start their careers, they should decide together how the trainer will be informed and what support options are available. A detailed account of the questions about the profession can be found at “adhspedia” [7].

Comorbidities of ADHD in adolescence.

Despite varying numbers in different studies, comorbid disorders in ADHD in adolescence are certainly the rule and not an exception [8]. 70% of adolescents with ADHD have at least one comorbid mental health disorder. The distinction to other disorders is not always clear and especially in sensitive developmental phases the question remains whether it is a comorbid or differential diagnosis. In clinical practice, the main finding is that the number and severity of comorbid disorders limit positive treatment outcomes.

Social behavior disorders and oppositional defiant behavior, the most common comorbid disorders in childhood, usually decrease. On the other hand, affective disorders and especially substance use (nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, etc.) increase significantly, especially in untreated ADHD, and persist into adulthood. Adolescents with ADHD use earlier and are more likely to become dependent [9]. No definite statement can be made about the reasons. The decisive factor may be risk-taking behavior, but also a short-term regulatory function, or the desire to join social groups and copy their behavior. The Canadian Caddra Guideline Group summarizes the body of research on ADHD and addiction development as indicating that treatment of ADHD is particularly important to counteract addiction development [8]. Especially for smoking, the importance of self-medication by nicotine, which has a strong dopaminergic effect, could be shown. Addictive disorders are not an absolute contraindication to treatment with stimulants. It is important to examine and pay attention to pharmacokinetic aspects. Medications must be used that have the slowest possible onset of action.

Among comorbid affective disorders, depression is particularly common, but the risk for bipolar affective disorder is also increased. Partial performance disorders that are already prevalent in childhood usually persist into adolescence and are often overlooked.

Problematic media consumption (gambling addiction) also occurs more frequently in ADHD. ADHD seems to be a particular risk factor, as the reward strategies of most games suit children and adolescents with ADHD in particular. It is amplified promptly and intermittently. Some authors assume that “gaming addiction” also corresponds to the principle of self-medication/treatment. To date, few studies have been conducted on this topic. However, these indicate that treatment of ADHD can also have a positive impact on problematic media consumption. Most importantly, however, the time spent with media must be “refilled” when media consumption is reduced. Children and young people must partly (re)learn to pursue leisure activities together with other young people and acquire social skills in the process.

Physical health is also increasingly impaired in ADHD, depending on the severity. The risk of accidents is already increased in childhood. There are significantly more accidents and hospitalizations. In adolescence, risky behavior increases even more and, together with inattention, leads to ADHD sufferers having more accidents or endangering themselves, for example, through unprotected sexual intercourse (increased pregnancies in adolescence).

Deciding on therapy design together

Due to the changes in the core symptomatology and possible additional comorbidities as well as the changing family dynamics, a joint assessment of the situation seems to be useful. The goal should be a new shared responsibility treatment contract. The basic recommendations for treatment, especially pharmacotherapy, do not change [10]. The site assessment should take place with the adolescent, their parents, and the treating child and adolescent psychiatric therapist, and should also include a voice in medication treatment. The Caddra guidelines explicitly emphasize sticking to topics relevant to young people in terms of language and content as well. Adolescence is a critical period for continuation of consistent medication; once-daily dosing can increase reliability [11]. In all age groups, even in children, but even more explicitly in adolescents, participation is significant in a decision for a certain treatment or especially in a decision for a drug treatment. Participatory decision-making also has a separate paragraph dedicated to it in the new S3 guidelines for ADHD [10].

Take-Home Messages

- The core symptomatology of ADHD changes in magnitude and characteristics during adolescence.

- The occurrence and importance of comorbid disorders are increasing.

- The changed symptomatology and family dynamic developments should lead to a new, jointly responsible treatment contract.

- It is possible that the initial diagnosis of ADHD may not be made until adolescence.

- Active recreation and sports (in groups) receive too little attention as a building block of treatment.

Related websites

|

Literature:

- Adam C, Döpfner M, Lehmkuhl G: The course of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adolescence and adulthood. Childhood and Development 2002; 11: 73-81.

- Tischler L, et al: ADHD in adolescence. Symptom change and implications for research and clinical practice. Journal of Psychiatry, Psychology and Psychotherapy 2010; 58: 23-34.

- Hauser TU, et al: Role of the medial prefrontal cortex in impaired decision making in juvenile attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2014; 71(10): 1165-1173.

- Hauser TU, et al: Cognitive flexibility in adolescence: neural and behavioral mechanisms of reward prediction error processing in adaptive decision making during development. Neuroimage 2015; 104: 347-345.

- Kordon A, Kahl KG: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adulthood. Psychother Psych Med 2004; 54: 124-136.

- Ludolph AG, Plener PL: Sport as a therapeutic component in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Psychotherapy in Dialogue 2011; 12: 221-223.

- adhspedia: ADHD and Occupation, www.adhspedia.de/wiki/ADHS_und_Beruf, last accessed 07/16/19.

- Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance (CADDRA): Canadian ADHD Practice Guidelines, Fourth Edition, Toronto ON. CADDRA, 2018.

- Frölich M, Lehmkuhl G: Epidemiology and pathogenetic aspects of substance abuse and dependence in ADHD. Addiction 2006; 52: 367-375.

- AWMF registry number 028-045: Long version of the interdisciplinary evidence- and consensus-based (S3) guideline “Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood” 2018.

- Wolraich M, et al: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adolescents: a review of the diagnosis, treatment, and clinical implications. Pediatrics 2005. 115(6): 1734-1746.

- Stahl SM: Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology, third edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2008.

- Stieglitz RD: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adulthood. Lecture Uni Basel 2019, last accessed on June 07, 2019.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(5): 16-21.