With the increasing clinical application of CAR-T cells, the practical aspects of therapy are a growing concern. Which patients should receive treatment using CAR-T cells outside of clinical trials? What is the optimal way to deal with side effects? And how can the effectiveness of therapy be maximized? These and other questions were discussed in an expert panel at this year’s European Hematology Association (EHA) Congress.

Two CAR-T cell products, axicaptagen ciloleucel and tisagenlecleucel, are currently approved in Switzerland, and three are already on the market in the USA. Most recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted approval for lisocaptagen maraleucel in February 2021. And research is being diligently conducted into further products, with clinical trials in full swing. It is no wonder that various questions about the practical implementation of CAR-T cell therapies are increasingly arising.

Patient selection: A tightrope walk

Different patient and disease characteristics play an important role in the selection of suitable candidates. Selection is the first critical step for the success of the therapy. It is important to exclude those patients with low chances of success or too high a risk of toxicity. And yet, the therapy should not be withheld from anyone who could potentially benefit from it. For example, in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), there are some candidates suitable for CAR-T cell treatment in the third line of therapy even among the non-transplantable patients – despite the mostly older age and the greater number of comorbidities in this patient group. Current data show that outcomes in patients over 65 years of age are comparable to those in younger patients. Apart from a slight increase in neurotoxicity, no adverse effects of increased patient age have been demonstrated to date.

Unlike age, performance status appears to have a significant impact on the chances of successful treatment with CAR T cells. The experts at the EHA Congress agreed on this. Because poor performance status is consistently shown to be an unfavorable condition for therapy, CAR-T cells should not be used in patients with an ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) status ≥3. For most clinical trials, the prerequisite is an ECOG status of 0-1. And even in the commercial setting, different guidelines exist in different countries.

Much uncertainty remains regarding the role of comorbidities in patient selection. Overall, however, CAR-T cell therapies are better tolerated than stem cell transplants and therefore place fewer demands on organ function in the heart, lungs, and kidneys. According to current knowledge, comorbidities play only a minor role in the risk of side effects. At least mild to moderate secondary diseases are not a problem for therapy with CAR-T cells and should not be considered a criterion for exclusion. Thus, for some patients who are not suitable for transplantation due to their comorbidities, CAR-T cells are a new, potentially curative option.

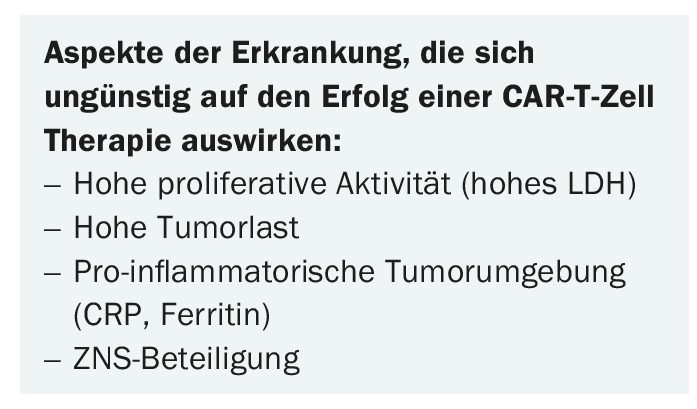

In addition to patient characteristics – especially the performance score – which must be considered in the selection of suitable candidates, various aspects of the disease also play a role in patient selection for CAR-T cell therapies. In particular, high proliferative activity, large tumor volume, signs of a pro-inflammatory tumor environment, and CNS involvement are considered unfavorable factors (Box). The reduction of tumor burden before starting CAR-T cell therapy – the so-called bridging – is an important topic in this regard, on which we can probably expect some more news in the future.

Side effects: Action or reaction?

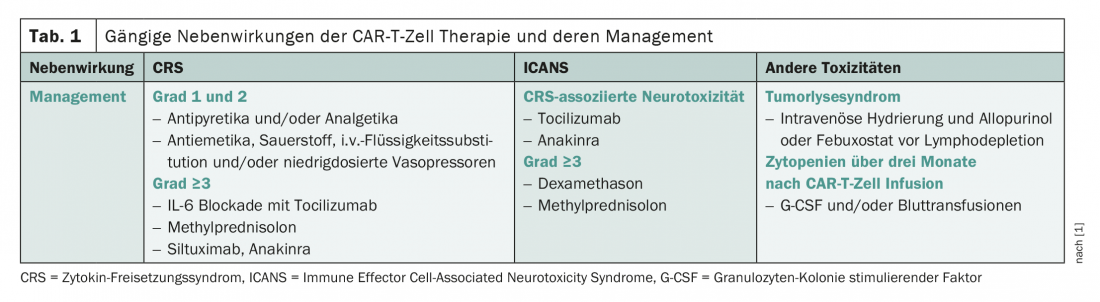

The side effect spectrum of CAR-T cells is characterized by cytokine release syndrome (CRS), a systemic inflammatory response, and neurotoxicity (Table 1) [1]. While CRS classically occurs in the first few days of treatment, nerve damage usually occurs in later phases of therapy. Complications that have been studied in less detail to date include tumor lysis syndrome and cytopenias. The latter have been rather underestimated so far, but have often proven to be problematic in clinical practice. Depending on the product, the side effect profile is somewhat different.

Also, patients with a larger tumor burden generally have an increased risk of toxicity. Nerve damage occurs more frequently in older patients. By knowing these risk factors, risk stratification and thus the timely taking of measures is possible. These consist of, among other things, the reservation of places in the intensive care unit and the prophylactic administration of tocilizumab or steroids.

Drug prophylaxis for CRS and neurotoxicity is not without controversy. For example, some studies show that side effects can be mitigated, but the effect on disease control is not insignificant. Thus, according to Pere Barba of Vall d’Hebron Hospital in Barcelona, each case should be assessed individually regarding the usefulness of prophylaxis. For example, he advises against tocilizumab prophylaxis for lisocaptagen maraleucel because of the profound risk of CRS. Overall, toxicities are now being treated increasingly aggressively. Whereas in the past specific therapy was usually only carried out from adverse drug reactions of almost third degree, now all toxicities from a grade 2 – i.e. moderate extent – are treated. In CRS, tocilizumab in particular is used; in neurotoxicity, steroids take the most important role in treatment. The effect of this earlier use of steroids on the efficacy of CAR T-cell therapy is a hotly debated topic. In addition, the increase in the risk of infection must not be neglected. In this tension, the best approach, according to Barba, is to treat aggressively at the beginning, but discontinue steroids as soon as possible. Unfortunately, some patients experience a new episode of neurotoxicity, a so-called “second wave,” during withdrawal.

In the future, the product could be modified to improve the management of side effects, and studies are ongoing. If severe toxicities occur, the CAR-T cells could be “switched off” using antibodies, for example. Whether this approach can prevent serious consequences of therapy remains to be seen. The experts at the EHA Congress were rather skeptical in this regard. The damage is then often already set, the inflammatory cascade triggered.

Before infusion: Optimize prerequisites

Before CAR-T cells can be infused, bridging therapies to reduce tumor burden, leukapheresis, and lymphodepletion are important steps that can have a significant impact on the success of treatment. Regarding the optimal strategy for disease control prior to CAR-T cell therapy, there is currently still great uncertainty, and the data are insufficient. What seems clear is that bridging therapy is necessary in most patients, as high disease burden indisputably confers poorer outcome and increased risk of toxicity. The experts at the EHA Congress agreed that disease progression should be prevented if at all possible, and be it by high-dose chemotherapy. In a retrospective study comparing different bridging procedures in terms of overall and progression-free survival of patients with DLBCL, radiotherapy performed best [2]. However, this analysis included only one hundred patients and was retrospective in nature.

To ensure the most efficient propagation, maintenance and function of CAR-T cells, endogenous cytotoxic immune cells and immunosuppressive cells are eliminated in the so-called “lymphodepletion”. Among other things, endogenous cytokines are released that promote T-cell proliferation. Studies usually use a combination of fludarabine and cyclophosphamide, which is administered over three days. Alternatively, there is the option of using bendamustine. One point of discussion is whether lymphodepleting chemotherapy should also be performed in those patients who – for example after stem cell transplantation – already have lymphopenia. This should become clearer with the increasing use of CAR-T cells, as should the question of whether better regimens for lymphodepletion are possible.

Timing is the critical factor for obtaining patient-derived T cells by leukapheresis. In particular, the collection must be performed with sufficient distance to bridging chemotherapy. This is of utmost importance for the quality of the product. As a rule of thumb, two weeks apart from chemotherapy, three days to one week apart from steroid administration. However, not only the timing of the pretreatment phase is of great importance for the success of CAR-T cell therapy, but also its overall duration. Currently, it takes about two months from initial contact to infusion of CAR-T cells – too long, considering that the disease progresses during that time. For example, a recently published study showed that of 108 patients initially eligible for CAR T-cell therapy, only 52 ultimately received the product [3]. Although there is now a noticeable trend toward shortening the waiting time, there is still room for improvement. Rising demand is placing increasingly high demands on infrastructure and pipelines, which first have to be built in many places. These requirements can only be met through efficient collaboration between clinics, centers and industry.

Source: Expert/Round Table session “How to best help patients succeed with CAR T cell therapies?” at the virtually conducted EHA Congress, June 11, 2021, Claire Roddie, London, United Kingdom and Pere Barba, Barcelona, Spain.

Literature:

- Yáñez L, Sánchez-Escamilla M, Perales MA: CAR T Cell Toxicity: Current Management and Future Directions. Hemasphere. 2019; 3(2): e186.

- Pinnix CC, et al: Bridging therapy prior to axicabtagene ciloleucel for relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2020; 4(13): 2871-2883.

- Carpio C, et al: Selection process and causes of non-eligibility for CD19 CAR-T cell therapy in patients with relapsed/refractory aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma in a European center. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021: 1-4.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2021; 9(4): 26-27 (published 9/20-21, ahead of print).