Cimicifuga racemosa is a herbal medicine commonly used in clinical practice in peri- and postmenopausal women. Like hormone replacement therapy, it is used in menopausal syndrome. Christine Bodmer, MD, of Bethesda Hospital, Basel, made recommendations for the use of one or another therapeutic agent at the 28th Swiss Annual Conference on Phytotherapy.

Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) exist comparing Cimicifuga racemosa (CR) with placebo. This showed that the placebo effect in menopausal syndromes should not be underestimated: perimenopausal symptoms usually improved under both forms of treatment, thus only rarely was a significant difference observed between the groups.

In contrast, RCTs comparing CR with hormone replacement therapy (HRT) show a significantly better effect of HRT compared with CR. Statements about the long-term effect of CR can neither be made in a positive nor in a negative sense due to the mostly rather short study duration (three to six, at most twelve months).

In animal studies in ovariectomized rats, trabecular bone density increased under CR, and even more so under estradiol administration. However, the few RCTs that also included bone density of CR-treated women in their measurement showed no significant differences between the treatment and placebo groups.

Risks and side effects

“Overall, few side effects occur under CR treatment, at around 5%. Most are mild forms such as headache, vomiting, nausea, fatigue, joint pain, and bleeding. Severe courses such as hepatitis or liver failure as well as tonic-clonic convulsions, cutaneous vasculitis, anaphylactic facio-oral edema, multi-organ and muscle failure are rare and, moreover, hardly ever clearly attributable to CR,” says Christine Bodmer, MD, of Bethesda Hospital, Basel.

“Under continuous-combined HRT, the risk of breast cancer increases slightly significantly. In the WHI study, the likelihood of cardiovascular disease was also increased under estrogen-progestin therapy. On the one hand, this was probably due to the high mean age of 63.2 years, on the other hand, the value decreased again to a non-significant level during follow-up. Under estrogen monotherapy, the risk of breast cancer decreases significantly, while that of cardiovascular disease remains the same. The risk of thrombosis is increased by two to three times the norm under peroral HRT, especially with continuous-combined, less so with estrogen monotherapy. In contrast, the risk of thrombosis is not additionally increased under transdermal HRT. The overall mortality for women beyond the age of 60 does not increase, for younger women it is even decreased”, Dr. Bodmer summarized the side effect profile of HRT [1, 2].

Which therapy for which patients?

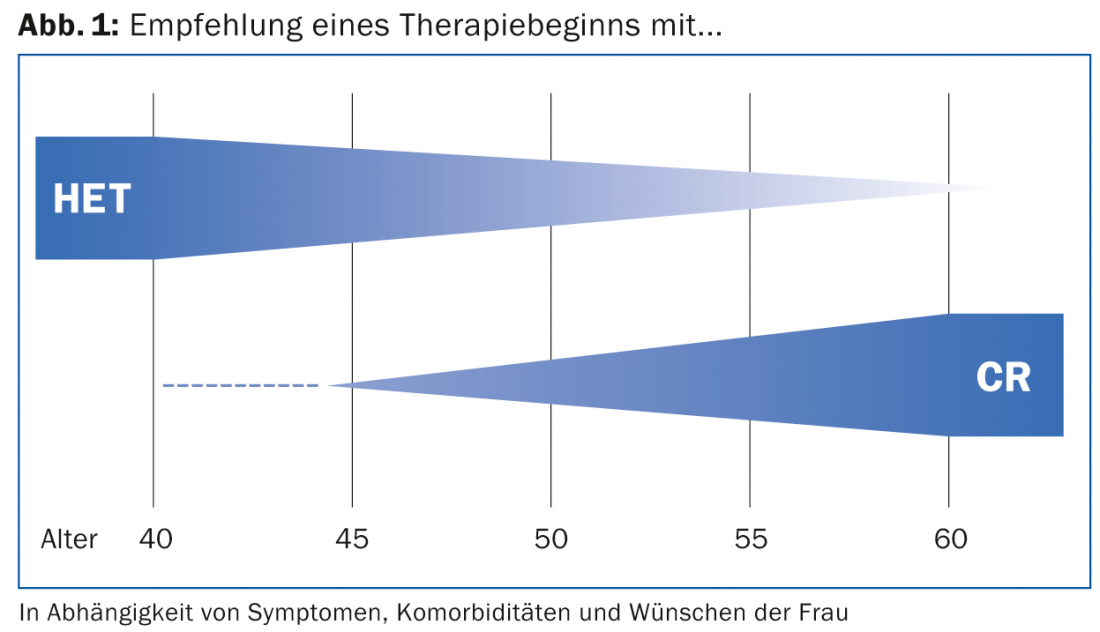

Women under 45 years of age (climacteric syndrome, regardless of bone status): In this patient population, administration of HRT is reasonable unless contraindications exist. HRT in young postmenopausal women reduces morbidity (osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease) and mortality that would be increased without this therapy [3].

Women aged 50/55 years and older (climacteric syndrome, no osteoporosis prophylaxis necessary): This patient population is well suited for CR therapy. After three to six months, the symptom complex (especially flushing and sweating) improves significantly, especially in women with pronounced symptoms. Unless there is a contraindication, hormone treatment is also possible.

Women over 50 years of age (menopausal syndrome, osteoporosis prophylaxis necessary): Since bone density increases under estrogen [4], the indication for HRT is given in this patient population (unless another contraindication exists). The increase depends on the dose. Several studies confirmed a significant reduction in fracture rate [5], which was maintained for years.

women regardless of age and bone status (climacteric syndrome, history of breast carcinoma): This patient population also seems to benefit from therapy with CR [6]. Moreover, in vitro studies show an antiproliferative effect on MCF-7 cells. In contrast to contraindicated continuous-combined HRT, detectable breast density (mammography) is not adversely affected [7].

Benefit-risk analysis decisive

“Depending on age, existing comorbidities and individual wishes, either CR or HRT therapy is appropriate. One must always examine the safety and efficacy profile together with the strengths and weaknesses just mentioned, i.e. perform a clean and individually adapted benefit-risk analysis,” Dr. Bodmer concluded her presentation (Fig. 1).

Source: “Phytotherapy with Cimicifuga racemosa versus hormone replacement therapy from the perspective of EBM and gynecological practice”, 28th Swiss Annual Conference on Phytotherapy, November 21, 2013, Baden.

Literature:

- Manson JE, et al: Estrogen plus progestin and the risk of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 2003 Aug 7; 349(6): 523-534.

- Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL: Changing concepts: menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012 Apr 4; 104(7): 517-527. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs014. Epub 2012 Mar 16.

- Svejme O, et al: Early menopause and risk of osteoporosis, fracture and mortality: a 34-year prospective observational study in 390 women. BJOG 2012 Jun; 119(7): 810-816. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03324.x. Epub 2012 Apr 25.

- The Writing Group for the PEPI trial: Effects of hormone therapy on bone mineral density: results from the postmenopausal estrogen/progestin interventions (PEPI) trial. JAMA 1996 Nov 6; 276(17): 1389-1396.

- Torgerson DJ, Bell-Syer SE: Hormone replacement therapy and prevention of nonvertebral fractures: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA 2001 Jun 13; 285(22): 2891-2897.

- Rostock M, et al: Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa) in tamoxifen-treated breast cancer patients with climacteric complaints – a prospective observational study. Gynecol Endocrinol 2011 Oct; 27(10): 844-848. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2010.538097. epub 2011 Jan 13.

- Raus K, et al: First-time proof of endometrial safety of the special black cohosh extract (Actaea or Cimicifuga racemosa extract) CR BNO 1055. Menopause 2006 Jul-Aug; 13(4): 678-691.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(3): 39-40