A lot has happened since pollen desensitizations in the 1960s. A tour d’horizon of the most important medical historical highlights from several decades of allergology research and practice.

Introduction: the allergy ward in Zurich

In 1948, Prof. Hans Stork (1910-1983), as a newly qualified private lecturer – inaugural lecture on the topic “Significance of allergy in the disease process” [1] – founded an “allergy ward” at the Dermatological University Clinic under the then clinic director Prof. Guido Miescher – an “allergy ward” with consultation hours for patients with allergies of the respiratory tract (rhinitis pollinosa et allergica, bronchial asthma), atopic dermatitis, anaphylaxis, food allergies, insect sting allergies, etc. This institution was the first allergy polyclinic in Europe. In the post-war years, Stork had studied allergy theory in various allergy centers in the USA and had become familiar with the practices of “desensitization therapy” there. Aqueous allergen extracts (Hollister-Stier Lab, Spokane) were imported from the USA for diagnosis and therapy.

After completing my medical studies in Zurich from 1956 to 1963, I worked as an assistant physician in the Medical Department of the City Hospital of Lugano from 1963 to 1964 and began my specialist training as a dermatologist in 1965 at the Dermatological University Clinic in Zurich. As part of the rotation, I joined the allergy ward in 1968 as a young resident. There I found my “ecological niche”. Already one year later I was promoted to senior physician i.V. 1; in 1971 to senior physician (Fig. 1). and in 1975, after my habilitation, to its head, a position I held until my retirement in 2003 and subsequently ran an allergology practice in Zollikerberg until 2013. Thus, I have witnessed almost 60 years of skin-focused allergology and have been able to follow the landmarks in practical allergology and allergy research during this time span.

Undoubtedly, a new era in allergology was marked in 1967-1968 by the discovery of a new class of immunoglobulins, IgE, as carriers of reagin activity and the provision of sensitive radioimmunological methods (RIST and RAST) for their detection [2–4]. Thanks to the discovery of IgE and its quantification, allergology also became “hopeful” for immunologists.

Pollen desensitizations at the allergy ward in the 60’s.

Pollen allergy patients formed a considerable part of the allergy ward’s patient population at that time. Patients underwent extensive prick testing with aqueous extracts (diluted 1:1000) on both forelimbs and, if negative, intracutaneous testing with the same concentration on the upper arms. All test-positive pollens were considered for “desensitization” in a mixed extract, which may have contained more than 40 (!) pollen species, including maple, willow, jasmine, lilac, black locust, linden, sedge and others. Treatment was ambulatory; the initial dose was 1:100 billion of stock solution, increased with subcutaneous injections three times weekly for three to five months to a maintenance dose of 0.2 ml (1:100,000) applied every two to four weeks for three to four years. Not without reason, allergists were called “shot doctors” at the time, and this practice was met with skepticism by the chairs of internal medicine and pediatrics, who called the dosages administered “homeopathic.”

The turning point: Semi-depotextracts, guide pollen and desensitization to the maximum dose

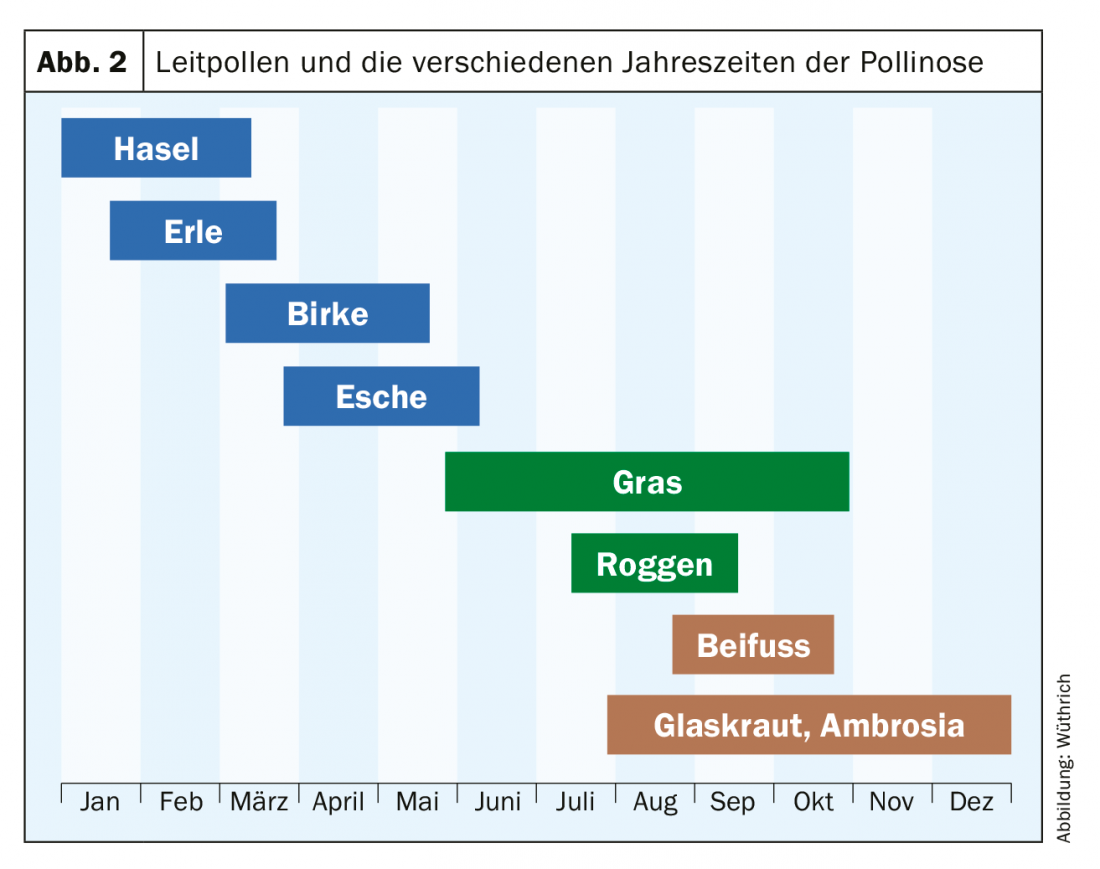

A decisive breakthrough in the practice of desensitization therapy was the introduction of allergens extracted with pyridine and adsorbed on aluminum hydroxide (so-called half-depotextracts), which allowed the administration of the vaccine only every 14 days. The original preparations of the Allpyral® brand from the USA were introduced in Switzerland with a limited selection of allergens (northern tree mixture of hazel, alder and birch pollen, grass mixture and mugwort, etc.) around 1965: The first results of pollen desensitization with these semi-depot preparations in Switzerland were published in 1967 by Ferdinand Wortmann of Basel and in 1968 by Wüthrich and Storck of Zurich, respectively [5,6]. Standardization of allergens was based on protein content in PNU (Protein Nitrogen Units). Starting with 20 to 50 PNU, the dose was increased to the maximum dose of 10,000 PNU, or to the highest tolerated concentration. This allergen concentration was much higher than in “homeopathic” desensitization with aqueous extracts. The conclusions of the two Swiss studies were that treatment with half-depot pollen extracts was an effective desensitization method (success rate in the first year 65-70%, in subsequent years 75-85%) and represented a major advance for both physician and patient because of the smaller number of injections. Based on the complaint calendar and the sensitization spectrum of anemophilic pollens present in sufficient numbers in the air, the concept of leading pollens (hazel, alder, birch for spring pollinosis, grasses/cereals for summer pollinosis, and mugwort for late summer/fall pollinosis) was introduced (Fig. 2). The company Allergomed AG (today’s company name: Allergopharma AG), Therwil supplied well standardized and durable test solutions in glycerol for prick testing as well as semi-depotextracts and oral preparations for subcutaneous and oral desensitization from the company Allergopharma in Reinbeck (Germany) from 1973 on. Novo-Helisen-Depot® with the most important inhalation allergens represented a new allergen preparation in which a two-step extraction process without pyridine was used. In 1977 our experience of pollen desensitization with Novo-Helisen-Depot® was published [7]. In a later work, we were able to prove the sustainability of the desensitization method with semi-depot extracts; especially also with regard to pollen asthma [8].

Semi-depotextracts for desensitization of allergic diseases – today this therapy is called allergen-specific immunotherapy (ASIT) -, replaced the lengthy “desensitization” with aqueous extracts, which was fraught with many side effects, and considered in the therapy solution only the clinically effective leading pollens of birch, hazelnut, alder, grasses and mugwort. It was not until the early 1990s that our research group demonstrated the importance of ash pollen in early season pollinosis [9]. With minor modifications, SIT with hemi-depotextracts is still the immunotherapy of choice, as confirmed by a meta-analysis [10].

Pollen immunotherapy today: allergen component-based diagnosis for indication.

Based on the complaint calendar, the triggering pollen can also be determined well anamnestically. Accordingly, a distinction is made between spring pollinosis (hazel, alder, birch and ash) from January/February to March/April and early summer pollinosis (mainly grass and cereal pollen) and, of importance for the southern regions, late summer pollinosis (mugwort, glasswort [Parietaria officinalis] and ragweed [Ambrosia artemifolia]). With regard to the initiation of a specific immunotherapy (SIT) in the late autumn/winter months, an allergological clarification is indicated today not only by means of skin tests, but also serologically with IgE determination on recombinant pollen allergens. For example, the early bloomers hazel, alder, and birch belong to the Fagales family (as do beech and oak, among others) and exhibit a high degree of cross-reactivity among themselves due to the main allergen of birch pollen Bet v 1. For specific immunotherapy of spring pollinosis, it is recommended today to determine not only sIgE to birch pollen, but also to rBet v 1 and r Bet v4/rtBet v 12 (minor allergens). The chances of success of specific immunotherapy are strongly related to the presence of sensitization to the major allergens. Are only spec. IgE antibodies against the minor allergens profilin (rBet v 2) and Ca-binding protein (rBet v 4) are detectable, the probability that SIT is not successful is high. However, if the patient exhibits spec. IgE antibodies to the major allergens, the chances of successful SIT are high. Because of the high cross-reactivity within the pollen of Fagales, SIT with only a birch pollen extract is usually sufficient. However, since ash is not a member of the birch family, this type of pollen, from Fraxinus excelsior and not Fraxinus americana [11], should always be tested. Serologically, Fraxinus excelsior or nOle e 1, a trypsin inhibitor protein, the major allergen of olive pollen (Olea europea) with extensive cross-reactivity with ash pollen, can be determined. If the result is clearly positive (>= CAP class 2), ash should be included in the SIT extract.

In case of grass/cereal pollen allergy, it is sufficient – due to the high cross-reactivity within the grass family (Poaceae, formerly Gramineae) – to determine the allergens of timothy grass (Phleum pratense ) rPhl p 1/ rPhl p 5b (g215) and rPhl p 7/rPhl p 12 (g214). If only specific IgE antibodies against the minor allergens Ca-binding protein (rPhl p 7) and profilin (rPhl p 12) are detectable, the prospects of successful treatment are low. However, if the patient has specific IgE antibodies to the major allergens (here rPhl p 1+ rPhl p 5b), a good response to SIT can be expected.

The co-seasonal scarification method according to Blamoutier (“Quadrillages cutanées”)

From the end of the 1950s to the beginning of the 1980s, only first-generation sedating antihistamines and systemic steroids (os and intramuscular) were available for symptomatic treatment of hay fever. The worldwide introduction and triumph of terfenadine, the first second-generation nonsedating antihistamine, did not begin until the 1980s. Approval in Switzerland was granted in 1981.

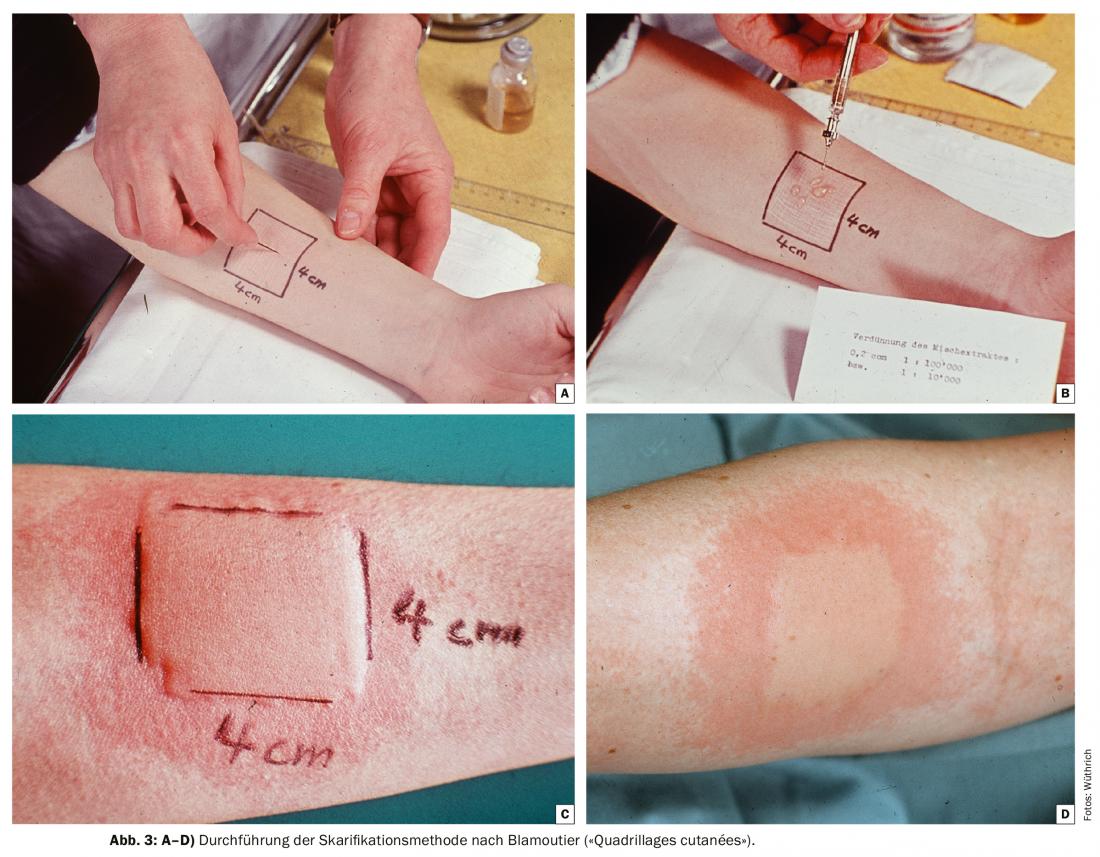

Great popularity in the allergy polyclinics of Switzerland in this “pre-antihistamine era” was the co-seasonal scarification method according to Blamoutier [12]. The French allergists introduced the “quadrillages cutanés” in 1959-1961. Pollen allergy sufferers were instructed to report for treatment when the first symptoms appeared on the conjunctiva and nasal mucosa, and to repeat the treatment if symptoms recurred. The intervals were usually one week, but could vary from three days to three weeks depending on the pollen count. This typically resulted in six to twelve sessions per season. The procedure is shown in Figures 3A-D. Interestingly, several patients reported freedom from symptoms immediately after wheal formation. A clinical study from Zurich showed a treatment success of 84% [13]. The mechanism of treatment success was unclear; in any case, no decrease in specific IgE antibodies (RAST) could be observed in serum immediately after quadrillage and 24 h thereafter. Even after the introduction of nonsedating antihistamines and topical steroids, patients continued to visit the allergy ward with the desire to undergo this method of treatment until the late 1980s. Today it has fallen into oblivion.

Bee venom “desensitization” with whole body extracts: great disillusionment

Desensitization for allergic reactions after insect bites, along with pollen desensitization, was the daily bread of allergists for many years. It was done with whole body extracts (GKE) of bees (B) and wasps (W), based on a study from 1930 [14]: USA researchers reported a beekeeper with respiratory bee dust allergy after entering the apiary and urticaria with Quincke’s edema after bee stings, who had been successfully desensitized with a whole body extract of bees (BGKE). Since this study, desensitization with aqueous B and W GKE, later with semi-depot extracts, has been practiced worldwide; mostly for life. We reported that “prophylaxis using specific desensitization with GKE had proven effective in our patient population, showing a failure rate with aqueous GKE of “only” 24% (n=54), or of “only” 17% (n=60) with semidepotextracts” [15]. The disillusionment came in 1978, when a paper by Hunt et al. demonstrated that, in contrast to pure bee venom, application of BGKE was no more effective than placebo treatment [16]. Today, SIT with pure bee and wasp venom is a success story.

The oral desensitization for inhalation allergies

In addition to subcutaneous immunotherapy, the allergy ward intensively tested the effect of oral desensitization in inhalant allergy, especially in children. The children or their mothers were informed that the “desensitization drops”, glycerol extracts (mainly from pollen) were to be taken in the morning on an empty stomach, not simply swallowed but kept in the mouth for a few minutes. Therefore, it was the so-called sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) today. [17]In a field report on this therapy, which had to be performed for at least 3 years, we concluded that “some physicians and clinicians are skeptical of peroral desensitization, although this method has been shown to be successful in children up to about 10-12 years of age . In fact, peroral desensitization has the advantages of being easy to perform and economical thanks to its administration by the mother, of being safe in terms of incidents and side effects and, last but not least, of being gentle on the infant patient, who does not have to suffer trauma due to many years of injections and visits to the doctor” [17]. Unfortunately, based on single placebo-controlled trials, but lasting only 1-2 years, this treatment was found to be ineffective, so it was temporarily abandoned. It was not until 1990-2002 that SLIT experienced a renaissance, mainly due to studies from the Mediterranean region. In the meantime, SLIT is well established thanks also to improved, standardized preparations, also in tablet form, based on numerous placebo-controlled studies [18].

Oral desensitization for cow’s milk allergy – previously rejected, now established

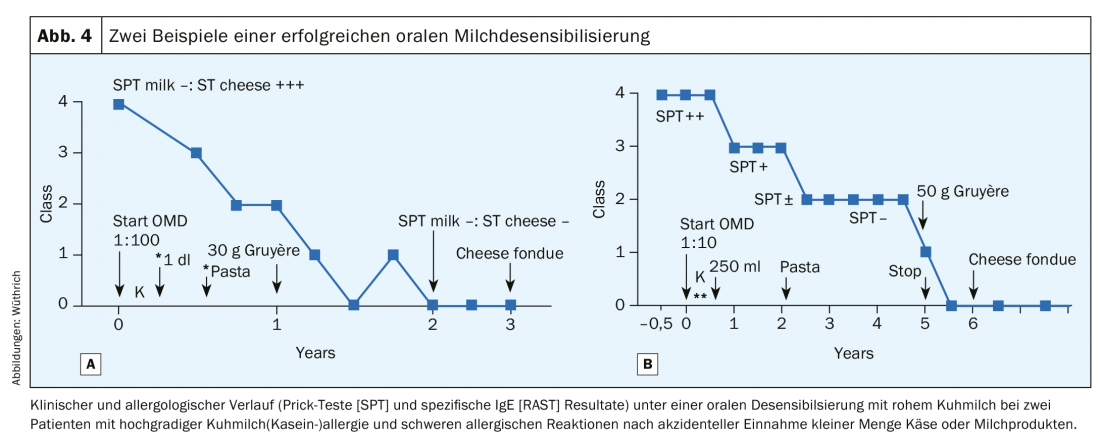

Since the 1980s, we have worked extensively on oral desensitization (OD) of food allergies, particularly cow’s milk allergy in adults, and have repeatedly described the methodology in detail [19,20]. We could show that in 50% of the cases under oral milk desensitization a complete tolerance (i.e. a true desensitization) to milk and cheese could be induced after a treatment period of 3-5 years. [20] (Fig. 4A and B). At least partial tolerance occurred in 25%, so that serious incidents after meals out no longer occurred. However, in 25% of cases, oral hyposensitization had to be interrupted because of repeated allergic reactions, even with dose reduction and concomitant therapy with antiallergic drugs [20]. During the initial phase of maintenance therapy of OD, 1 dl of cow’s milk must be taken daily, because a break could break the achieved tolerance again. This first phase thus corresponds to tolerance induction: however, if the daily application of the maintenance dose is continued for months, even years, true desensitization occurs; negativity of skin tests and specific IgE determinations to milk proteins and caseins are detected. This method was rejected on the grounds that no double-blind, placebo-controlled studies were available and thus no scientific evidence of its efficacy (!) [21]. Now this method has been rediscovered by pediatricians [22–23], but one searches in vain for our work in the bibliography [24–26].

New strategies to improve allergen-specific immunotherapy.

The progress of ASIT in recent years is mainly based on a better standardization of allergen extracts, on the development of modified therapeutic extracts (allergoids, e.g. Allergovit® or Polvac®) [27] and the molecular-biological characterization of natural allergens up to the genetic engineering of important recombinant allergens [28–29]. Perspectives are also shown in the combined use of SIT with anti-IgE vaccines (rhuMab-E25, omazulimab, Xolair) [30]. In any case, ASIT and SLIT will maintain or even expand their place in the treatment of IgE-mediated diseases in the near future [31].

Literature:

- Storck H: Significance of allergy in the disease process. Schweiz Rundschau Med [PRAXIS] 1948, No. 32 (offprint).

- Johansson SGO: Raised levels of a new immunoglobulin class (IgND) in asthma. Lancet 1967; 2(7523): 951.

- Ishizaka K, Ishizaka T: Human reaginic antibodies and immunoglobulin E. J. Allergy 1968; 42: 330.

- Wide L, Bennich H, Johansson SGO: Diagnosis of allergy by an in vitro test for allergen antibody. Lancet 1967: 2(7526): 1105-1107.

- Wortmann F: Results of pollen desensitizations with alum-precipitated pyridine extracts (Allpyral). Schweiz Med Wschr 1967; 97: 489.

- Wüthrich B, Storck H: Desensitization results in pollen allergic patients with allpyral and with aqueous extracts. Schweiz Med Wschr 1968; 98: 653-658.

- Wüthrich B: On the specific hyposensitization of pollinosis. Results of a two-year study with a new allergen preparation Novo-Helisen-Depot. Schweiz Rundschau Med [PRAXIS] 1977; 66: 260-266.

- Wüthrich B, Günthard HP: Late results of hyposensitization therapy of pollinosis follow-up of 328 cases 2 to 5 years after completion of syringe treatment with aqueous or semidepot allergen extracts. Schweiz Med Wschr 1974; 104: 713-717.

- Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Peters A, Wahl R, Wüthrich B: On the significance of ash pollen allergy. Allergology 1994; 17: 535-542.

- Compalati E, et al: Specific immunotherapy for respiratory allergy: state of the art according to current meta-analyses. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2009; 102: 22-28.

- Wüthrich B: Ash is not ash. Allergology 2006; 29: 231-235.

- Blamoutier P, Blamoutier J, Guibert L: Traitement co-saisonier de la pollinose par l’application d’extraits de pollens sur des quadrillages cutanés: Résultats obtenus en 1959 et 1960. Revue francaise d’allergie 1961; 1: 112-120.

- Eichenberger H, Stork H: Co-seasonal desensitization of pollinosis with the scarification-method of Blamoutier. Acta Allergol 1966; 21(3): 261-267.

- Benson RL, Semenov HZ: Allergy in its relation to bee sting. J Allergy 1930; 1: 105.

- Wüthrich B, Häberlin G, Aeberhard M, Ott F, Zisiadis S: Desensitization results with aqueous and semi-depotextracts in insect venom allergy. Schweiz med Wschr 1977; 107: 1497-1505.

- Hunt KJ, et al: A controlled trial of immunotherapy in insect hypersensitivity. New England J Med 1978; 299(4): 157-161.

- Lätsch C, Wüthrich B: On peroral desensitization of inhalant allergies in childhood. Treatment results. Schweiz Med Wschr 1973: 103: 342-347.

- Bergmann K-Ch: Efficacy and safety of sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) – a detailed status review. Pulmonology 2006; 60: 241-247.

- Wüthrich B, Hofer T: Food allergies. III. therapy: elimination diet, symptomatic, drug prophylaxis and specific hyposensitization. Schweiz Med Wschr 1986; 116: 1401-1410 & 1446-1449.

- Wüthrich B: Oral desensitization with cow’s milk in cow’s milk allergy. Pro! In: Wüthrich B, Ortolani C (eds), Highlights of Food Allergy. Monogr Allergy 1996, 32; 36-240. Basel: Karger.

- Bahna SL: Oral desensitization with cow’s milk in IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy, contra! In: Wüthrich B, Ortolani C (eds), Highlights of Food Allergy. Monogr Allergy 1996; 32, 233-235. Basel: Karger.

- Staden U, et al: Rush oral immunotherapy in children with persistent cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clinical Immunol 2008; 122: 418-419. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.06.002. Epub 2008 Jul 7.

- Keet CA, et al: The safety and efficacy of sublingual and oral immunotherapy for milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 129: 448-455. 455.e1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.10.023. Epub 2011 Nov 30.

- Wüthrich B: Recent aspects of the diagnosis and therapy of food allergy. Presented on the basis of selected case studies of milk allergy. Allergology 1987; 10: 370-376.

- Wüthrich B, Stäger J: Allergie au lait de vache chez l’adulte et désensibilisation spécifique au lait par voie orale. Méd & Hyg 1988: 46: 1899-1905.

- Bucher C, Wüthrich B: Oral desensitization in cow’s milk allergy. Giorn it allergol immunol clin 2000; 10: 119-120.

- Mühlethaler K, et al: On hyposensitization of pollinosis. Results of a controlled study over three years with two depot allergoid grass pollen extracts – aluminum hydroxide-adsorbed allergoid (AGD) and tyrosine-adsorbed allergoid (TA). Schweiz Rundschau Med [PRAXIS] 1990; 79: 430-436.

- Valenta R, et al: The recombinant allergen-based concept of component-resolved diagnostics and immunotherapy (CRD&CRIT). Clin Exp Allergy 1999; 29: 896-904.

- Valenta R, Linhart B, Swoboda I, Niederberger V: Recombinant allergens for allergen-specific immunotherapy: 10 years anniversary of immunotherapy with recombinant allergens. Allergy 2011; 66: 775-783.

- Kuehr J, et al: Efficacy of combinant treatment with anti-IgE plus specific immunotherapy in polysensitized children and adolescents with seasonal allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002; 109: 274-280.

- Nedergaard Larsen J, Broge L, Jacobi H: Allergy immunotherapy: the future of allergy treatment. Drug Discovery Today 2016; 21: 26-37.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2019; 29(5): 8-12