The prevalence of current actinic keratosis (AK) sufferers in the population increases with age. Depending on UV exposure, the development of AK is relevant from the age of 40. In Australia up to 60% of this age group is affected, in European latitudes 15-30% can be assumed. A number of 70% of AK-affected patients in their 70s can be expected, ranging from single AK to field cancerization.

Prevalence, as the rate of current sufferers in the population, increases with age. Depending on UV exposure, the development of actinic keratoses (AK) is relevant from the age of 40. In Australia up to 60% of this age group is affected, in European latitudes 15-30% can be assumed [1]. A number of 70% of AK-affected patients in their 70s can be expected, ranging from single AK to field cancerization.

The incidence, as a measurement of new cases in a year, is given by the Robert Koch Institute as 229,750 new cases for 2016. The incidence of disease in 2844 consecutive patients seen in Swiss general practices was 25% [2]. AK is thus one of the most common diagnoses in dermatology and binds patients and physicians in a treatment partnership. In this context, education, prevention, targeted therapies are needed.

Pathogenesis

The basic cause is UV-induced damage to keratinocytes in the epidermis. Constitutionally, skin types I and II favor the development of AK. Other acquired predispositions include childhood sunburns and cumulative UV exposure. Possible UV-related molecular damage is explained in a recent review [1].

So far, p53 mutations and mutations of the Ras oncogene have been identified as genetic causes. p53 is active in cell cycle control. Mutations of p53 prevent necessary apoptosis. Involvement of p53 in the genesis of AK is thought to occur in up to 80% of cases. Immunosuppression, whether drug-induced or not, also contributes to increased development of AK.

In a recent study using next generation sequencing, beta-human papillomaviruses (HPV), previously highlighted as prominent, were not shown to be significantly important in AK compared to normal skin, but gamma1-HPV4 types were significantly enriched in AK. The statements on virus persistence, variations even of new HPV types, etc. depending on the localization are still insufficient.

Hydrochlorothiazide use has been shown to increase the risk of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) 1.2-fold and the risk of squamous cell carcinoma (PEK) 4-fold. A case-control study of 400 patients with cardiovascular disease showed no correlation of AK with thiazide diuretics [3].

Classifications

The commonly used Olsen clinical classification has been in place since 1991. It is used in studies and also in the guideline.

- Olsen grade I: mild – barely visible and weakly palpable AK,

- Olsen grade II: moderate – well visible and palpable AK,

- Olsen grade III: severe – clearly visible and severely hyperkeratotic AK [4].

Also worth knowing are the clinical histologic and histologic classifications of Cockerell et al. 2000 and by Röwert-Huber et al. 2007 [5,6].

However, the current lack of an enforceable classification is reflected in country-specific variations, such as the AK classification of the British Association of Dermatologists:

- AK grade 1 mild – minimal scaling patch,

- Grade 2 moderate – moderate scaly patch,

- Grade 3 severe – hyperkeratotic lesion.

Quite essential is the recognition that clinical findings and associated histology do not necessarily correlate, i.e., increasing clinical findings need not correspond to increasing malignant potential, e.g., in terms of invasiveness. And another key point about the clinic and histology is important: In field cancerization, the biopsy of an included AK should not be considered representative of the setting. Therefore, current work is increasingly turning to a histological workup of possible prognostically relevant criteria. Work by Dirschka et al. on the growth pattern of atypical keratinocytes confirm an invasive potential also of initial AK (grade I according to Olsen) [9].

What does this mean for the treating physician? The primary clinical assessment currently remains. Biopsies should be performed urgently if a lesion is unclear or progresses rapidly. At this time, there is an indication for early and broadly applied therapy for all AK. Only a better assessment and scientifically based prognosis can enable a more targeted therapy intervention. In existing AK, the primary goal is to avoid progression to invasive PEK.

Prevention

Primary prevention is intended to prevent the development of AK. In individual behavior, this means avoiding personal risks. However, changes in the environment that may be involved in disease development must also be addressed. Related actions include, for example, sun protection in kindergartens or a ban on the use of a solarium for those under 18 years of age (SR 814.711 “Ordinance to the Federal Law on Protection against Hazards from Non-Ionizing Radiation and Sound” came into force on 01.06.19).

Secondary prevention is focused on early diagnosis of AK. Counseling of patients and prompt therapies are intended to cure or mitigate the course. Screening examinations are one option. In Switzerland, free biennial skin cancer screening is offered to insured persons over the age of 35. Even though AK are not a defined component of skin cancer screening, high hit rates are found, especially in older subpopulations.

With regard to the possible development of PEK, tertiary prevention should be mentioned as a diagnostic pillar and therapy to prevent secondary damage. In multiple AK, the lifetime risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma (PEK) is assessed at 6-10% over a 10-year period.

With respect to pathogenesis, early, consistent sun protection should precede everything. Textile sun protection (headgear, glasses, clothing) and adequate use of UV protection preparations, which must include UVA and UVB protection, are necessary. Denser clothing can provide a UV Protection Factor of 50, meaning <1/50 of UV radiation passes through, 2% at most. For the correct application of UV-protective agents, it is necessary to refer to timely application and sufficiently thick, uniform and repeated application. The skin type-related calculable allowed length of stay is thus not extendable.

Although the acceptance of sun protection increases with age and especially after the first UV damage has been detected, it can be improved overall and especially among young people. Regular sun protection campaigns are initiated in Switzerland by the Cancer League. Brochures and short videos provide information about the dangers of overexposure to the sun and sun protection recommendations. Furthermore, the National Skin Cancer Campaign, organized by the Swiss Society of Dermatology and Venereology (SGDV), has taken place annually since 2006. Among other things, it promotes public awareness of consistent sun protection and early detection examinations.

If the risk of skin cancer is high, e.g. in transplant patients, the vitamin D level should be determined and, if necessary. be substituted. Adequate production of vitamin D occurs with moderate daily sun exposure of approximately 20-25% of the body (e.g., face, hands, and arms) for at least 5 minutes approximately 2-3×/week [7].

Prevention with other agents such as selenium, vitamin A and beta-carotene are not recommended as measures for skin cancer prevention. Nicotinamide can be used for prevention, especially concerning BCC and PEK, in patients previously suffering from Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer (NMSC) and organ transplanted patients. Studies on caffeine, as a protective factor, and nicotine and alcohol as negatives are not convincing.

Clinic

The spectrum of lesions ranges from a small red macula, a low to clearly superimposed sessile keratosis, pigmented, crustose or atrophic lesions to a field carcinization (Fig. 1) . This is characterized by multiple AK surrounded by visible UV-related skin damage, including a red-brownish-whitish patchy and proportionally atrophic skin. However, there is no uniform definition of field cancerization.

AK occur primarily in UV-exposed skin areas, such as the hairless top of the head, forehead, cheek, nose or ears (“sun terraces”). But AK can also be found on the décolleté, neck and extremities.

Diagnostics

AK is primarily diagnosed clinically visually and palpatorily. Characteristic features can be detected by dermoscopy. White dots arranged in a cloverleaf pattern perifollicularly are described as “rosette marks”. Typical of non-pigmented AK is the “strawberry” pattern, characterized by follicular openings with keratotic plugs surrounded by a reddish pseudonetwork. In pigmented AK, a brown to gray pseudonetwork composed of multiple brown to gray dots or globules arranged around the follicular openings is apparent. Progression to a PEK may be visible by gross keratoses and minute crustose inclusions.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy is a diagnostic imaging technique that provides non-invasive microscopic assessment of the upper layers of the skin using a monochromatic point light source with a penetration depth of approximately 300 µm. AK is characterized by loss of normal honeycomb structure with atypia and pleomorphism of epidermal keratinocytes, parakeratosis, and blood vessel dilatations. Compact overlying hyperkeratosis can significantly complicate the analysis of deeper structures in some cases, which may limit the diagnosis of invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

Another imaging technique is optical coherence tomography, which uses electromagnetic radiation in the near infrared range (700-1300 nm). Here, depth section images with a penetration depth of approx. 1.5-2.6 mm and horizontal images are created at the same time. AK show acanthosis with well preserved junctional zone. In invasive squamous cell carcinomas, the regular layering of the epidermis is abolished and the junctional zone can no longer be clearly delineated. Severe hyperkeratosis can also lead to limitations in diagnosis. First attempts of virtual consultation on AK have been published. After critical consultation and instruction of the patient on AK, regular overview and close-up images are a basis for possible care [8].

Therapy

The indication for therapy of AK should be made in synopsis of the clinical picture, risk factors, comorbidities, life expectancy, and the patient’s wishes and compliance. The AKASI score can be applied for clinical severity classification and objectification of therapeutic success of AK on the head [9].

The current “S3 Guideline Actinic Keratosis and Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Skin” provides an overview of approved treatment options, indications and application parameters [10]. Two major blocks are to be considered: non-invasive procedures and invasive / mechanical-destructive procedures. Regarding immunosuppressed transplanted patients and occupationally ill patients, modified treatment criteria not further presented here arise [10].

Non-invasive procedures

Topical drug-assisted procedures

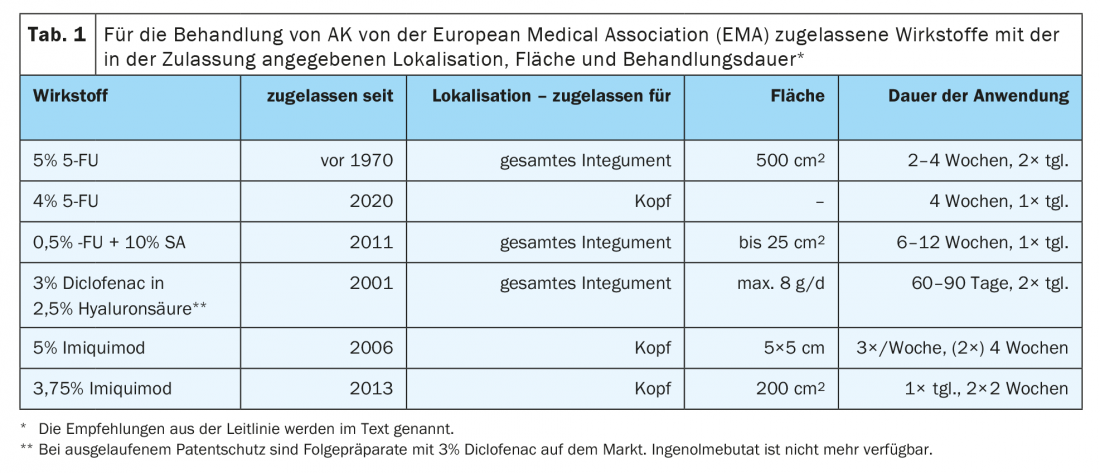

For individual consideration, possible decision criteria and recommendations from the guideline are briefly outlined below. Regarding the mechanisms of action and side effects, we would like to refer to current literature available online (Tab. 1) [11].

3% Diclofenac in 2.5% Hyaluronic Acid can be used on larger areas of the entire body at a time. The advantage of this treatment option is a low spectrum of side effects. Application 2× daily for 60-90 days up to a maximum amount of 8g per day is possible. According to the guideline, 3% diclofenac in 2.5% hyaluronic acid should be offered for single or multiple Olsen grade I-II AK in immunocompetent patients or in field cancer [10]. The response rate ranges from 25% to 89%, depending largely on the clinical findings. In years of progression, this treatment option has often been used, so other options must be weighed.

5-Fluorouracil 5% cream should be offered for the treatment of single and multiple AK grade I-II according to Olsen’s guideline. Field-directed therapy with 5-fluorouracil 5% cream can be used for field cancerization [10]. 5% 5-FU with 2× daily application for 2-4 weeks may cause side effects such as redness, itching, burning, erosion, ulceration, and scabbing. Stronger local reactions are more likely to be found in atrophic aged skin or when taking antico-agu-lants. Studies have shown a very good response rate and long-term success also in terms of recurrences [12]. Response rates show a wide range, ranging from 38% to 96%.

4% 5-FU is also approved for the head region and is used in AK grade I-II. With comparable efficacy to 5% 5-FU, use is only 1× daily and promises less pronounced side effects, resulting in improved patient adherence to therapy [13]. 0.5% 5-FU with 10% SA was approved primarily for lesion-directed therapy of AK. In the post-admission study, AK grade I and II showed complete healing of 75% of lesions and complete healing in 50% of cases after 8 weeks compared with placebo treatment in the field-directed therapies. The duration of treatment is usually 6-12 weeks. 0.5% FU with 10% SA is to be applied daily with a brush. It forms a barely visible film and is accompanied by good tolerance.

Imiquimod is approved for use in the head region. 3.75% Imiquimod demonstrates a reliable and longer-term response here, especially in the presence of a clearly inflammatory response. Typical side effects are pruritus, local pain and crusting. Therefore, shorter therapy intervals with a “2 on – 2 off – 2 on” rhythm were established. This means an application 1× daily for 2 weeks and after a 2-week break another application for 2 weeks. This leads to good therapy adherence in patients when used in a side effect-adapted manner. According to the guideline, imiquimod 3.75% cream should be offered field-directed for multiple grade I-II AK according to Olsen and for field carcinogenesis in immunocompetent individuals on the face or hairless capillitium [10]. Response rates range from 34% to 82%.

Treatment of AK with 5% imiquimod is possible but has moved behind the 3.75% concentration of imiquimod in treatment frequency due to more severe side effects. Use in the setting of combined treatment of superficial BCC, for which 5% imiquimod is approved, and existing AK remains to be considered.

PDT is based on conversion of 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) and metyhlaminolevulinic acid (MAL) to the photoactive metabolite protoporphyrin IX, which accumulates in neoplastic cells and is activated by light. This forms reactive acid species that induce apoptosis, among other things. Various externals and light sources are available for PDT. The guideline summarizes: Conventional photodynamic therapy with 5-aminolevulinic acid or its methyl ester (5-ALA or MAL) should be offered on a field-directed basis for single or multiple grade I-II AK according to Olsen and for field carcinomatization [10].

MAL-containing cream can be used as a finished drug and is applied to the treatment area with a thickness of 1 mm. After 3 hours of occlusion, irradiation with 570-670 nm (75 J/cm2) or alternatively with 630 nm (37 J/cm2) can be performed. If the AK does not heal completely, it can be reapplied after 12 weeks. ALA is available in the form of a patch and a gel containing an ALA nanoemulsion (BF-200 ALA). Up to 6 ALA patches with a size of 4 cm2 can be used simultaneously. They can be used for both single and multiple AK. Four hours after incubation, exposure to a narrow spectrum red light lamp (630 nm) is performed.

The BF-200 ALA gel is lesion and field-approved. The 2g tube is sufficient for an area of 20 cm2 with 1 mm thick application. After 3 hours of occlusion, irradiation with red light broad spectrum or narrow spectrum lamp follows. BF-200 ALA has also been approved for use on extremities, trunk and neck since 03/2020. Formulated by Swiss medic 2018, the following applies to the use of BF-200 ALA: “Treatment of actinic keratoses (AK) of mild to moderate intensity on the face and scalp (grade I-II according to Olsen) and field cancers in adults.” Combining PDT with local therapies, firstly in terms of desquamation and keratolysis or therapeutically with imiquimod or 5-FU, may improve efficacy.

Daylight PDT can be used with both MAL-containing cream and BF-200 ALA gel. Less pain with such treatment is due to the slower onset of protoporphyrin IX with shorter incubation time (<30 minutes) and subsequent exposure (2 hours). MAL in combination with daylight (daylight-MAL-PDT) should be offered on a field-directed basis for nonpigmented, single or multiple grade I-II AK according to Olsen, and for field carcinomatization of the face and capillitium in immunocompetent individuals [10]. A new approach is home-based daylight PDT, in which patients apply the photosensitizer themselves and then expose themselves to daylight.

Meta-analyses serve to a certain extent a ranking of therapies: Therapeutic successes showed the highest cure rate for BF-200 ALA with 75.8%, followed by 5% 5-FU with 59.9%, ALA patches with 56.8%, 5% imiquimod with 56.3%, 3.75% imiquimod with 39.9%, and 3% diclofenac in 2.5% hyaluronic acid with 24.7% [14]. In another meta-analysis, PDT also showed the highest success in healing, followed by 5% 5-FU, 5% imiquimod, and 3% diclofenac in 2.5% hyaluronic acid [8].

Invasive mechanical procedures

Cryosurgery is a widely used procedure, often combined with local therapeutics or even PDT. Using liquid nitrogen of -196 ˚C, a temperature of -25˚C is targeted in the treated skin area by contact stamping or spraying. This is mostly achieved by applying 15-60 seconds and icing 2 times. However, clear standards have not been established. It is recommended lesion-directed for single or multiple grade I-III AK according to Olsen in immunocompetent individuals [10]. It not infrequently leaves behind hypopigmented skin areas, so that aesthetic aspects can also come into focus in accordance with age and the course of the disease.

The domain of operative procedures is rather incumbent on disseminated standing, especially also more pronounced AK. In this regard, the guideline recommends surgical removal of AK grade I-III according to Olsen for single lesions in both immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients, e.g., by curettage, shallow ablation, or complete excision [10]. An advantage of this method is the simultaneous diagnostic confirmation. Shave excision and inadequate coverage of deeper structures are cautioned against. Compared to non-invasive procedures, these approaches score lower in the cosmetic evaluation simply because of the formation of scars.

Laser procedures are popular because of their good feasibility and, according to the guideline, should be offered for single or multiple AK grade I-III according to Olsen as well as for field cancerization in immunocompetent patients. With the Er:YAG orCO2 laser, AK can be ablated quickly and specifically. A supplementary histological backup as well as photo documentation are recommended. Laser therapy followed by local treatment, e.g., with 5% 5-FU, results in better drug delivery [15].

An interesting summary by Steeb et al. addresses the question “The more the better?” It has been shown that combination therapy can increase the effectiveness of therapeutic success. In particular, a combination of lesion-directed and field-directed therapy may be useful. A significant increase in success is still critically questioned without further studies [16].

Developments

Tirbanibulin is a new synthetically produced agent that has FDA approval for AK in the head since December 2020. Tubulin polymerization is inhibited. This is followed by cell cycle arrest (G2/M phase) and apoptosis. Two pivotal Phase III placebo-controlled trials report complete response rates of 44% and 54% at day 57, significantly better than the placebo effect (5%, 13%) [17]. 1% Tirbanibulin is applied locally to approximately 25 cm2 once daily for 5 days. Day 8 shows erythema, scaling, pruritus and pain, mild to moderate in severity and rapidly regressing.

From the group of flavonoids, subgroup of polyphenols and belonging to the catechins, the development of a sinecatechin (green tea extract) for the treatment of AK is being pursued. As a causal therapeutic approach, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticarcinogenic effects of catechins can be mentioned. The antiproliferative effect on keratinocytes even in the context of photocarcinogenesis has been demonstrated [18]. Evidence-based treatment data for AK remain to be generated.

Four additional compounds are named in a potential development for the treatment of AK [19]: Potassium dobesilate has anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenic, and anti-tumoral effects as an inhibitor of FGF signaling and prostaglandin synthesis. Response rates of approximately 60% for AK have been published in an older phase II study. Tuvatexib is a hexokinase 2 modulator Comp-1. Apoptosis follows via interaction with hexokinase at mitochondria. Analogous to 5-FU, paclitaxel was advised as a locally applicable chemotherapeutic agent. It binds to β-tubulin and inhibits the cytoskeleton. A “proof of principle” for paclitaxel, as locally applicable submicron particles, exists as well as for “furosemide plus digoxin,” but without further studies having been performed in AK.

Summary

Actinic keratoses (AK) remain a future topic due to a further increasing incidence. In view of the chronic course of the disease, the aging patient who requires long-term therapeutic management, early education and primary as well as secondary prevention become more important.

Current developments in pathogenesis, risk assessment, critical evaluation of classifications, preventive measures and diagnostics are outlined. Therapeutic options and concepts are outlined based on the S3 guideline “Actinic keratosis and squamous cell carcinoma” of the skin. The current status as well as possible future therapies will be presented.

Take-Home Messages

- AK is primarily diagnosed clinically.

- The term field cancerization is currently not based on a clear definition.

- Previous AK gradings do not reliably correlate with risk of invasiveness.

- The indication for treatment is based on numerous, individual criteria and, in addition to remission, serves to prevent progression as well as the development of PEK.

- Prevention and therapies are established on a broad basis such as guidelines and health policy measures.

Literature:

- Reinehr CPH, Bakos RM: Actinic keratoses: review of clinical, dermoscopic, and therapeutic aspects. An Bras Dermatol 2019 Nov-Dec; 94(6): 637-657; doi: 10.1016/j.abd.2019.10.004.

- Dziunycz PJ, Schuller E, Hofbauer GFL: Prevalence of Actinic Keratosis in Patients Attending General Practitioners in Switzerland. Dermatology 2018; 234(5-6): 214-219; doi: 10.1159/000491820.

- Warszawik-Hendzel O, Olszewska M, Rakowska A, et al: Cardiovascular Drug Use and Risk of Actinic Keratosis: A Case-Control Study. Dermatol Ther 2020; 10: 735-743; doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00405-8.

- Olsen EA, Abernethy ML, Kulp-Shorten C, et al: A double-blind, vehicle-controlled study evaluating masoprocol cream in the treatment of actinic keratoses on the head and neck. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991 May; 24(5 Pt 1): 738-743; doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70113-g.

- Cockerell CJ: Histopathology of incipient intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (“actinic keratosis”). J Am Acad Dermatol 2000 Jan; 42(1 Pt 2): 11-17; doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.103344.

- Röwert-Huber J, Patel MJ, Forschner T, et al: Actinic keratosis is an early in situ squamous cell carcinoma: a proposal for reclassification. Br J Dermatol 2007 May; 156 Suppl 3: 8-12; doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07860.x. Erratum in: Br J Dermatol 2007 Aug; 157(2): 431.

- Holick MF: Vitamin D: a D-Lightful health perspective. Nutr Rev 2008 Oct; 66(10 Suppl 2): S182-194; doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00104.x.

- Dhariwal S, Hari T, Kaur K, et al: Virtual consultation for actinic keratosis. BJGP Open 2020 Oct 27; 4(4): bjgpopen20X101126; doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101126.

- Dirschka T, Pellacani G, Micali G, et al: A proposed scoring system for assessing the severity of actinic keratosis on the head: actinic keratosis area and severity index. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017 Aug; 31(8): 1295-1302; doi: 10.1111/jdv.14267.

- Oncology Guideline Program. S3 Guideline Actinic keratosis and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin 2019. AWMF Registry Number:032/0220L, www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/aktinische-keratosen-und-plattenepithelkarzinom-der-haut.

- Nashan D, Hüning S, Heppt MV, et al: Actinic keratoses: current guideline and practice-based recommendations. Dermatologist 2020; 71: 463-475.

- Walker JL, Siegel JA, Sachar M, et al: 5-Fluorouracil for Actinic Keratosis Treatment and Chemoprevention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Invest Dermatol 2017 Jun; 137(6): 1367-1370; doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.12.029.

- Dohil MA: Efficacy, Safety, and Tolerability of 4% 5-Fluorouracil Cream in a Novel Patented Aqueous Cream Containing Peanut Oil Once Daily Compared With 5% 5-Fluorouracil Cream Twice Daily: Meeting the Challenge in the Treatment of Actinic Keratosis. J Drugs Dermatol 2016 Oct 1; 15(10): 1218-1224.

- Vegter S, Tolley K: A network meta-analysis of the relative efficacy of treatments for actinic keratosis of the face or scalp in Europe. PLoS One 2014 Jun 3; 9(6): e96829; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096829.

- Nguyen BT, Gan SD, Konnikov N, Liang CA: Treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in situ on the trunk and extremities with ablative fractional laser-assisted delivery of topical fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015 Mar; 72(3): 558-560; doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.11.033.

- Steeb T, Wessely A, Leiter U, et al: The more the better? An appraisal of combination therapies for actinic keratosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020 Apr; 34(4): 727-732; doi: 10.1111/jdv.15998.

- Kempers S, DuBois J, Forman S, et al: Tirbanibulin Ointment 1% as a Novel Treatment for Actinic Keratosis: Phase 1 and 2 Results. J Drugs Dermatol 2020 Nov 1; 19(11): 1093-1100.

- Zink A, Traidl-Hoffmann C, et al: Green tea in dermatology – myths and facts. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2015 Aug; 13(8): 768-775.

- Cramer P, Stockfleth E, et al: Actinic keratosis: where do we stand and where is the future going to take us? Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2020 Mar; 25(1): 49-58.

DERMATOLOGY PRAXIS 2021; 31(2): xx-xx.