A condensed overview of risk factors for pressure ulcer development in the bio-psycho-social model of international classification and measures for prevention. Condition of wounds and treatment recommendation in clear tabular presentation.

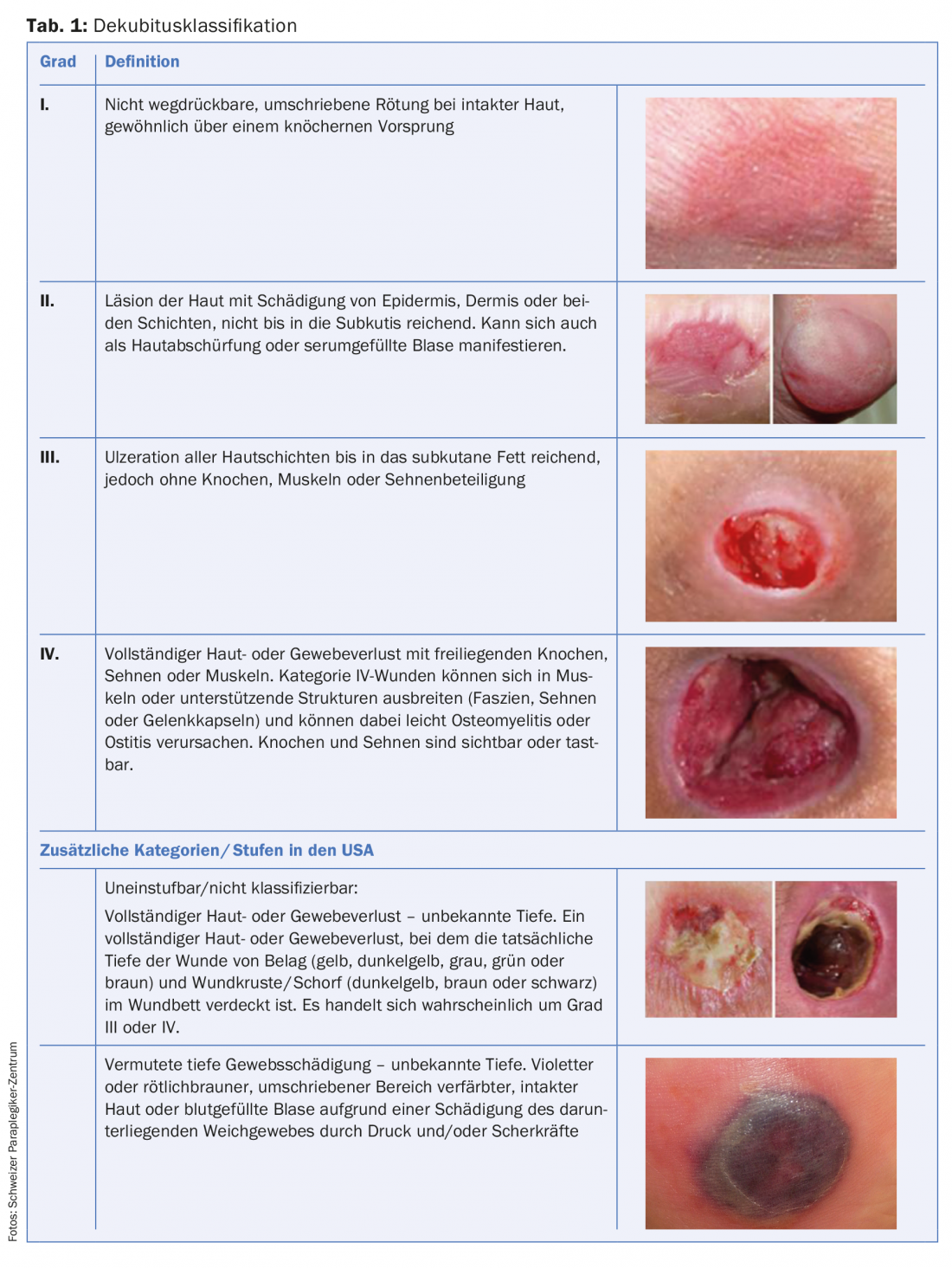

A pressure ulcer is localized damage to the skin and/or underlying tissue, usually over bony prominences, as a result of pressure or pressure combined with shear forces. There are a number of other factors that are actually or presumably associated with pressure ulcers; however, their significance remains to be clarified [1]. Pressure ulcers are classified into four grades. In addition, two categories are described to integrate deep tissue damage and occupied wounds into the pressure ulcer topic (Table 1).

The greater the contact pressure and the longer the exposure time to a particular skin area, the greater the risk of pressure ulcers. Due to an individual pressure tolerance curve, tissues react differently in each person [2].

Compression of capillary vessels results in tissue ischemia, accumulation of toxic substances, and tissue loss. Other factors such as shear forces and friction can additionally contribute to tissue damage. The first sign of a superficial pressure ulcer is the fixed redness, which has not completely faded after twelve hours of relief. Failure to adequately relieve this site will result in further tissue damage to the bone. Some pressure ulcers arise from depth and are first recognizable by a hardening or accumulation of fluid at depth [2].

Decubitus has become established as a name in German-language literature just like decubital ulcers, pressure sores or pressure ulcers. In English, the following terms were discussed, which emphasize different aspects and may be used equivalently: “pressure ulcer”, “decubitus ulcer”, “deep tissue injury”, “pressure sore”, etc.

Risk factors and risk assessment

High-risk groups include people with advanced age, reduced mobility, after surgery, in intensive care, or with paraplegia. The risk of pressure ulcers is influenced by various factors such as increasing age and the associated skin changes (reduced skin regeneration, skin resistance). The risk factors summarized in Table 2 must be observed.

Risk assessment

In order to implement adequate preventive measures and plan interventions at an early stage, the pressure ulcer risk should be assessed regularly. In the geriatric setting, the Braden and Norton scales are used as structured assessments and are supplemented by the expertise of professionals for individualized prevention. Regular training for professionals is additionally useful and contributes to an improvement in the quality of care and a reduction in incidence.

Risk assessment using a validated risk scale is not useful in people with spinal paralysis, because spinal paralysis already represents a high risk and too many preventive measures would rather be initiated [3]. Individualized risk assessment results from regular observation and professional expertise in the bio-psycho-social model of the International Classification of Functioning (ICF) [4]. In an inpatient treatment context, the interdisciplinary team assesses the overall risk from nursing and medical assessment complemented by the therapeutic perspective. In the outpatient context, the patient himself, if necessary supported by caring relatives or outpatient caregivers, should be trained to carry out the comprehensive management with prevention, early detection and initiation of further measures. In addition, specialized outpatient services such as ParaHelp or wound outpatient clinics can be consulted. The risk of pressure sores increases in the short term:

- in case of deterioration of the general condition

- for infections and fever

- After operations

- during immobilization in bed.

Measures of pressure ulcer prevention

Regular skin control includes inspection and palpation of the skin, especially the areas at risk (Fig. 1) . Depending on the functional and personal abilities of the patients, skin control can be performed by themselves. If necessary, nursing staff or/and caring relatives take over this task, which should be specifically clarified in each case. In patient education, skin control competency is an essential element (Table 3) [5].

Home monitoring intervals are based on the phase of life or the phase of acute treatment or rehabilitation. In the stable outpatient setting, skin should be safely checked in the morning after sleep and in the evening after mobilization. An increased skin control interval is necessary in case of infections, deteriorated general condition, sedation-induced immobilization and skin abnormalities. All observations deviating from the normal skin situation must be documented and adequate nursing interventions initiated.

Complementary measures for prevention

Specialists such as nutritionists, occupational or physiotherapists or psychologists may be involved in the implementation of complementary measures [6,7]. Basically, adapted and relieving positioning in bed and in the wheelchair as well as regular relieving in the wheelchair are indicated. Immobilization in bed should be avoided. Patients should not be in a wheelchair continuously for more than six hours and should take a lunch break if possible. If necessary, pressure relief through soft positioning with appropriate mattresses (static or dynamic anti-decubitus mattresses) and adapted positioning material (pillows, positioning wedges, etc.) is required. The seat cushion, sitting position, etc. must be individually adapted to the patient. The positioning intervals must also be adjusted on a dynamic system, because pressure relief by changing the positioning is fundamentally necessary.

Skin care adapted to the patient avoids skin lesions. The skin should also be protected from moisture and irritation. It is important not to leave any foreign objects in the bed or wheelchair. Care should also be taken to avoid friction in clothing and shoes (e.g. seams and folds), shoes can be one to two sizes larger.

The individual nutritional situation should be assessed with a structured assessment and nutritional counseling should be provided to ensure adequate protein intake, good vitamin and nutrient intake, adjusted caloric and fluid intake [8].

These measures are supported by integrated psychotherapy that targets behavioral modifications for relapse prevention, treats psychiatric comorbidities, and uses coping strategies to help optimize compliance. Finally, patient participation plays a central role in pressure ulcer prevention. Patient education that generates understanding is indicated.

Pressure ulcer therapy

Depending on the classification of the pressure ulcer, a conservative therapy concept in an outpatient setting is possible or an operative inpatient treatment concept becomes necessary [9]. Due to the complexity, the treatment concept should include the bio-psycho-social aspects according to the ICF model [2].

Conservative measures for pressure ulcers [10,11] include consistent pressure relief using special mattresses and exposure of the affected areas. Causes should be evaluated and eliminated if possible, and risk factors should be minimized preventively. Wound treatment should follow the TIME concept (T = “tissue removal”, debridement; I = “infection control”, infection control; M = “moisture management”, promotion of granulation; E = “edge protection”, epithelization) (Tab. 4) . If necessary, storage materials and aids must be adapted again to the individual circumstances. The patient as a contributor is always at the center of effective prevention, so rehabilitation such as learning new self-care techniques, transfer, new movement patterns, and psychological care may be recommended along with other measures.

Because of the high recurrence rates, surgical treatment in a specialized center with appropriate experience and established interdisciplinary treatment teams is recommended. The “modified Basel pressure ulcer concept” integrates the following principles, has proven increasingly successful in recent years and is being continuously developed in an international network [2,11]:

- Pressure relief

- Wound debridement

- Wound treatment/wound conditioning

- Treatment of general diseases, risk factors, nutritional optimization.

- Defect coverage through plastic surgery

- Education/Aftercare/Prophylaxis.

Important differential diagnosis

Moisture-related skin lesion and incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD) are defined as irritant contact dermatitis, the majority of which occurs in patients with fecal and urinary incontinence. Due to the destroyed skin barrier function, inflammation is triggered with weeping skin and superficial wounds. Secondary skin infections are often the result (Table 5). Related terms are diaper dermatitis, moist lesions, perineal dermatitis or rash.

Risk factors include frequent episodes of fecal and urinary incontinence, use of occlusive incontinence products, poor skin condition (skin defense is compromised, aging skin, influence of steroids), and elevated body temperature.

For the treatment of IAD, moisture management is particularly important in addition to the treatment principles described above for pressure ulcers.

Take-Home Messages

- Pressure sores occur in typical locations over bony prominences. The elderly and people with paraplegia are particularly at risk.

- The depth of the pressure ulcer according to the international classification EPUAP leads to different treatment concepts (conservative or surgical).

- Pressure relief as the most important first measure requires special planning in the outpatient setting.

- Wound healing and local wound care should be regularly monitored by specialized professionals, as it is a complicated wound healing process.

- Risk factors in the bio-psycho-social understanding should be imperatively analyzed in a structured way and treated in an individualized way.

Literature:

- Haesler E (ed.): Update 2014: National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Quick Reference Guide. Osborne Park, Western Australia: Cambridge Media 2014.

- Scheel-Sailer A, et al: Pressure ulcer – an update. Schweiz Med Forum 2016; 16: 489-498.

- Mortenson WB, Miller WC: A review of scales for assessing the risk of developing a pressure ulcer in individuals with SCI. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 168-175.

- World Health Organization (WHO), et al: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: WHO 2005.

- Kottner J, et al: Measuring the quality of pressure ulcer prevention: A systematic mapping review of quality indicators. International Wound Journal 2017. DOI: 10.1111/iwj.12854

- Atkinson RA, Cullum NA: Interventions for pressure ulcers: a summary of evidence for prevention and treatment. Spinal Cord 2018. DOI: 10.1038/s41393-017-0054-y [Epub ahead of print].

- Hellmann S, Rösslein R: Practical nursing management of pressure ulcers. Hanover: Schlütersche 2007.

- Dietetics. Spinal Cord Injury Evidence-Based Nutrition Practice Guideline 2014; Available from: http://andevidencelibrary.com/topic.cfm?cat=3486.

- Panfil E-M, Schröder G: Care of people with chronic wounds: Textbook for nurses and wound experts. Bern: Verlag Hans Huber 2015.

- Roche R: Incident pressure ulcer. Rehab Basel: Roland de Roche 2012.

- Kreutzträger M, et al: Outcome analyses of a multimodal treatment approach for deep pressure ulcers in spinal cord injuries: a retrospective cohort study. Spinal Cord 2018. DOI: 10.1038/s41393-018-0065-3 [Epub ahead of print].

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2018; 28(1): 4-10