Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and their manifestations vary widely, and comorbid disorders are common. Life crises or minor stresses can reactivate previous traumas, but do not themselves cause PTSD. Many mental illnesses, especially addiction, can mask PTSD. PTSD may also be overlooked in cases of long-standing trauma, chronic pain syndromes, distrustful and hostile behavior, and severe organ disease. The course of therapy comprises three phases: Stabilization including establishment of external security and inclusion of the social environment, trauma exposure and reintegration including further stabilization and reassessment. Trauma treatment is usually followed by a long process of accompaniment, reorientation and social reintegration.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is multifaceted in terms of symptomatology and the resulting limitations in the bio-psycho-social context of life. It is also sometimes difficult to distinguish from other mental illnesses, especially borderline personality disorder. PTSD is a possible result of one or more stressful events that would cause pronounced distress in almost anyone.

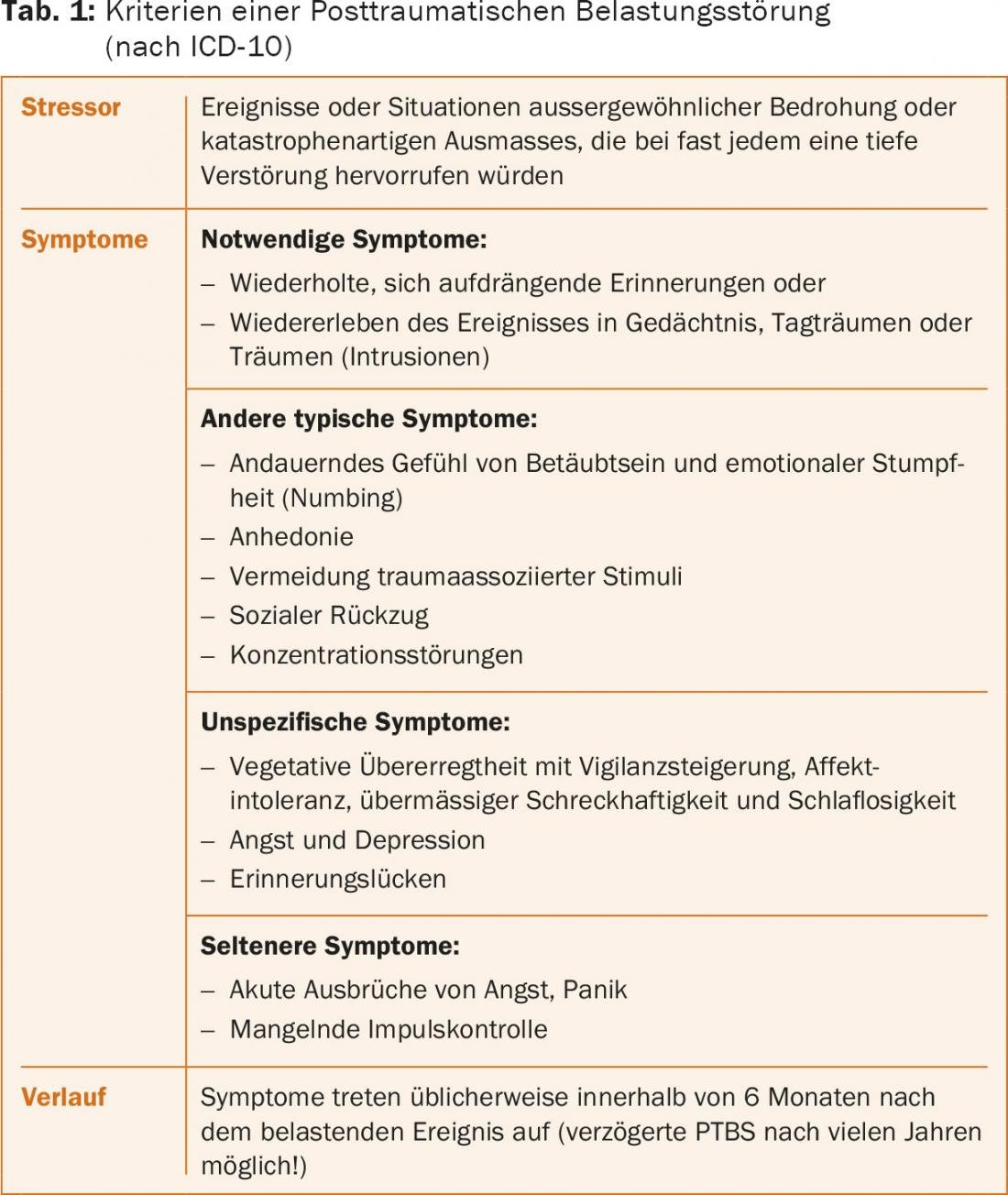

Already in the first half of the 20th century, the corresponding symptoms were observed in victims of serious railroad accidents, soldiers of the two world wars and Holocaust survivors. In systematic descriptions, we find the typical symptoms that we also consider today as characteristic reactions to traumatic experiences: imposing, stressful thoughts and memories of the trauma, reliving the events in memory, daydreams or dreams (intrusions), avoidance behavior, emotional numbness with disinterestedness or alienation from other people (tab. 1) [1–3].

Epidemiology

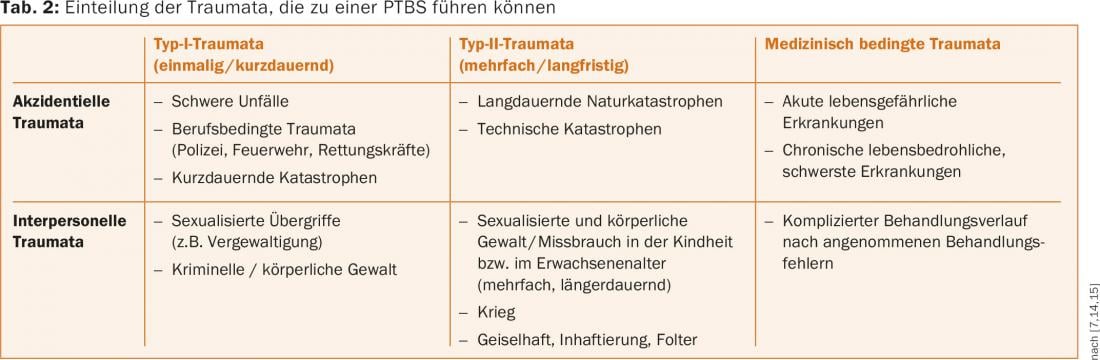

PTSD is thought to have a lifetime prevalence of 1-7% [3]. The different figures are based on methodological differences, but also on the frequency of traumatic events in different countries and the high number of unreported cases. Further, the prevalence of PTSD is closely related to the type of event, but is not linear. There is no evidence of a threshold above which a manifest disorder is very likely to develop. Indisputably, prolonged, so-called “man-made” traumatization (rape, torture, war) most often leads to PTSD with about 50%, followed by other violent crimes with up to 25% [4]. Individual risk factors include family history, lack of social support, low socioeconomic status, early separation and loss, comorbidity, youthful or advanced age, and, in terms of events, duration, recurrence, helplessness, guilt, and irreversible loss (Table 2).

Diagnostics

The diagnosis of PTSD is predominantly clinical, since 1978 using the criteria of the ICD (ICD-9, ICD-11 in progress) or the DSM (now DSM-5). Internationally recognized, psychometric test procedures are used, e.g. the “Impact of Event” scale (revised version) for the assessment of psychological stress consequences [5] or the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV dissociative disorders [6]. Until now, PTSD has been classified as an anxiety disorder. The high incidence of comorbid disorders such as depression, other anxiety disorders, somatization disorders, addiction, or sleep disorders may complicate the diagnosis of PTSD [7].

Etiology and pathogenesis

All accepted explanatory and treatment approaches (psychodynamic, cognitive-behavioral, and systemic schools) base the genesis of illness on both an event that took place and specific subjective interpretations of the event. If the emotional and cognitive integration of the traumatic experience is not successful or insufficient, the events cannot be stored coherently in memory – in the form of the so-called narrative. The memory contents remain fragmented and the memory details as sensory and emotional impressions always current, there is always only a “here and now” of (re)experiencing, no “there and then” of memory. Intense and persistent feelings of helplessness, powerlessness, threat, and intense fear repeatedly trigger the physiological stress cascade [4].

Therapy of PTSD in three phases

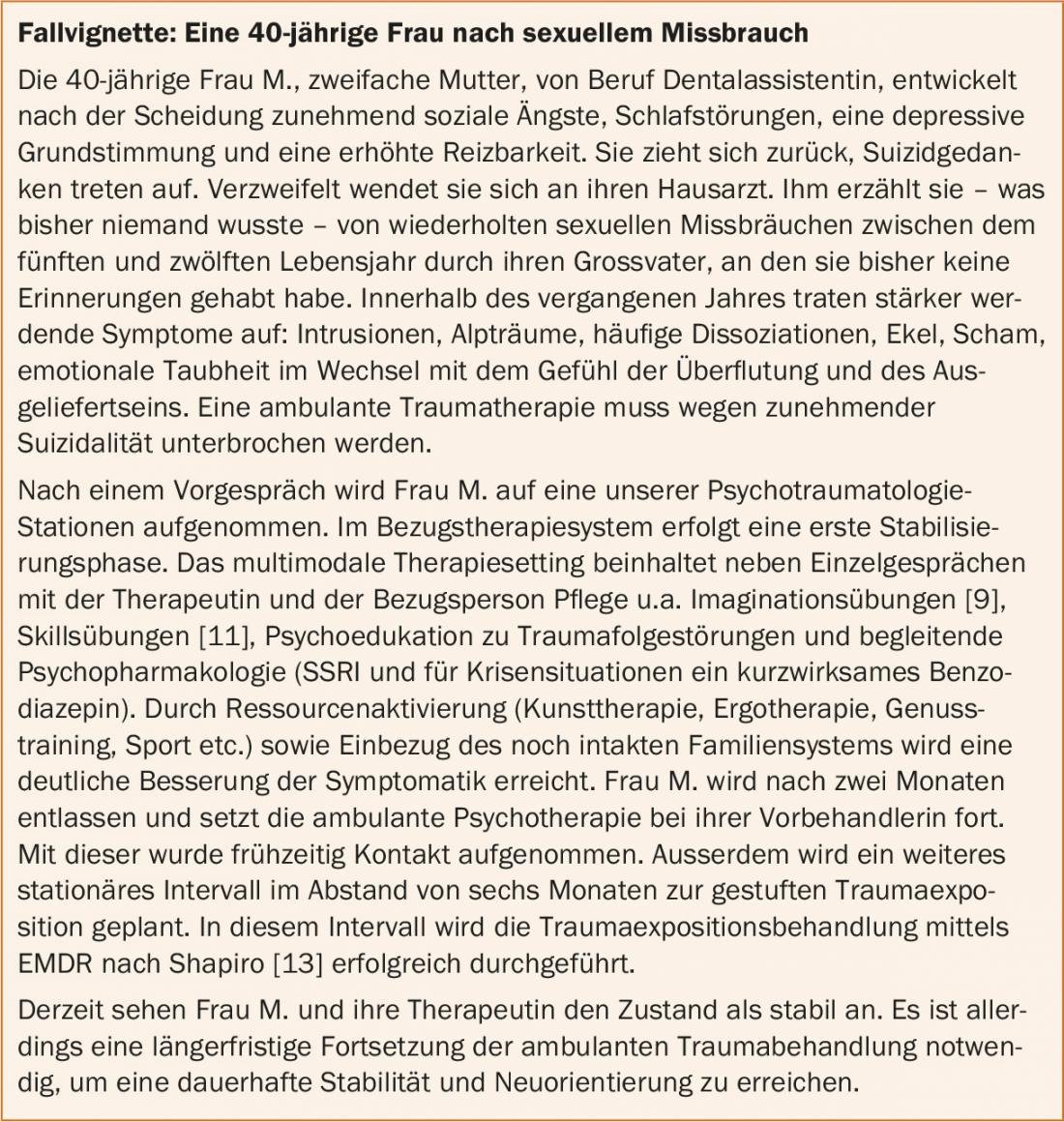

The goal of PTSD therapy is the recovery of previous ego functions or the acquisition of functions that were not developed as a result of the traumatization [8]. Initially, early connection to specialized outpatient settings for diagnosis and initiation of therapy is indicated (e.g., psychotherapists with trauma therapy qualifications and experience, psychotraumatology centers). At the same time, creating a safe environment, breaking off contact with offenders, and activating social support systems are important [2]. The actual treatment is multi-phase (three phases are common) based on recognized procedures such as Multidimensional Psychodynamic Trauma Therapy [2], Psychodynamic Imaginative Trauma Therapy [9] or Trauma-Centered Psychotherapy [10].

Typically, an outpatient setting is the primary treatment continuum. Cases of complex PTSD may require an inpatient treatment interval of several weeks followed by continuation of outpatient therapy.

Phase I: Stabilization

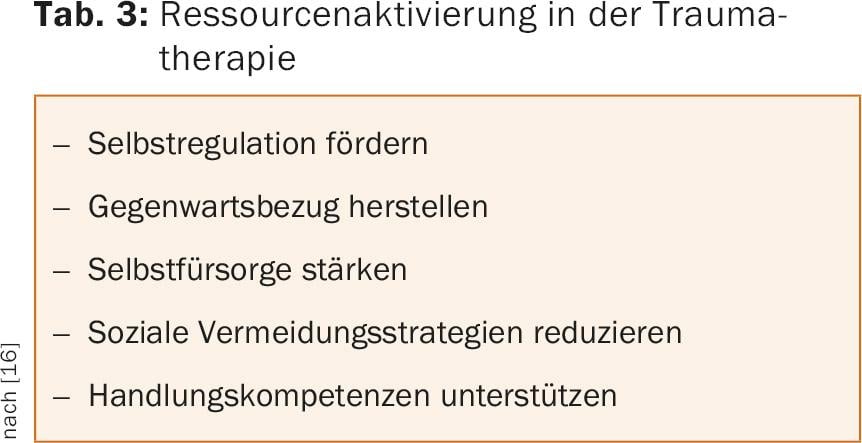

Phase I serves to establish a trusting therapeutic working relationship and possibly pharmacotherapy. Phase I includes psychoeducation, mindfulness exercises, and learning skills [11], dealing with flashbacks and dissociations, and reactivating existing resources. The latter helps to regain autonomy and competence to act within the framework of a consistent orientation towards the present.

Phase II: Confrontation with traumatization

Phase II represents the confrontation with the traumatization, provided there are no contraindications (danger to self or others, severe dissociative states, psychotic decompensation, substance abuse, persistent contact with the perpetrator, or lack of compliance). Trauma treatment should also be deferred in cases of suicidality, severe self-harm, psychotic symptomatology, severe dissociation, and affect intolerance.

Traumatically fixed memories and sensory fragments are consciously activated in a protected setting and transferred to the non-threatened present. This is done using a variety of techniques originally from different schools of therapy, e.g., screening techniques [10], Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET) [12], Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) [13], or cognitive reappraisal [4].

Trauma exposure leads to trauma synthesis, the narrative is formed and integration into the biography is made possible. In this context, affected individuals need repeated motivation from outside to maintain the ongoing learning process through exercises and patience (Tab. 3).

Phase III: Reintegration

Phase III includes the final reintegration of the traumatization. This phase is associated with mourning as well as saying goodbye to and re-evaluating the past. In order to build a life after and with the trauma, further therapeutic support is urgently needed, including social and vocational rehabilitation if necessary.

Situation in Switzerland

Diagnosis, specialized outpatient and inpatient treatment, and reintegration of people with PTSD are challenges in many countries. In Switzerland, the situation has improved significantly over the last decade. Thus, Switzerland’s first department for disorder-specific inpatient trauma therapy at Clienia Littenheid AG is celebrating its tenth anniversary this year. In the meantime, inpatient services have been established at other locations, e.g. at ipw Winterthur.

Networking with outpatient services as well as professionally experienced medical and psychological therapists varies from canton to canton. Overall, the care situation is developing favorably, with the Swiss training centers making significant contributions (Swiss Institute for Psychotraumatology, Winterthur; Medical Faculty of the University of Zurich and Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy of the University Hospital Zurich (USZ); Psychological Institute, Health Psychology of Childhood and Adolescence, University of Zurich). A prognosis regarding increased utilization by people from crisis and war zones seems premature, but overall we expect an increasing need for professionals trained in psychotraumatology.

Literature:

- Dilling H, et al: International classification of mental disorders, ICD-10, chapter V (F). Clinical diagnostic guidelines. Bern: Huber 2013.

- Fischer G, Riedesser P: Textbook of psychotraumatology. 4th ed. Munich: UTB Ernst Reinhardt 2009.

- Flatten G, et al. (eds.): Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, AWMF guideline and source text, 2nd ed. Stuttgart: Schattauer 2004.

- Ehlers A, Clark DM: A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther 2000; 38: 319-345.

- Maercker A, Schützwohl M: Assessment of psychological stress consequences: The Impact of Event Scale-revised version. Diagnostica 1998; 44: 130-141.

- Gast U, et al: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders. Interview and manual. Göttingen: Hogrefe 2000.

- Maercker A, Karl, A: Posttraumatic stress disorder. In Perrez M, Baumann U (Eds.): Textbook clinical psychology – psychotherapy (3rd ed.). Bern: Huber, 2005, pp. 970-1009.

- Rudolf G: Psychodynamic psychotherapy: working on conflict, structure and trauma. 2nd ed. Stuttgart: Schattauer 2014.

- Reddemann L: Psychodynamic imaginative trauma therapy. 6th ed. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta 2011.

- Sachsse U (ed.): Trauma-centered psychotherapy. Stuttgart, New York: Schattauer 2004.

- Linehan MM: Dialectical-behavioral therapy for borderline personality disorder. Munich: CIP Media 1996.

- Schauer M, et al: Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET). A Short-Term Intervention for Traumatic Stress Disorders. 2nd ed. Cambridge Mass.: Hogrefe & Huber Publ. 2011.

- Shapiro F: EMDR: principles and practice. Handbook for the treatment of traumatized people. Paderborn: Jungfermann 1998.

- Landolt MA: Childhood psychotraumatology. Göttingen: Hogrefe 2004.

- Schelling G: Post-traumatic stress disorder in somatic disease: lessons from critically ill patients. Prog Brain Res 2008; 167: 229-237.

- Sack M: Gentle trauma therapy – resource-oriented treatment of trauma sequelae. Stuttgart: Schattauer 2010.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 14(4): 10-13.