Tumor breakthrough pain is very common in patients with malignancies. Yet they are often overlooked or misjudged. However, the sudden and severe attacks of pain put a strain on sufferers both physically and psychologically. Rapid and effective pain relief with, for example, fast-acting fentanyl is therefore a top priority.

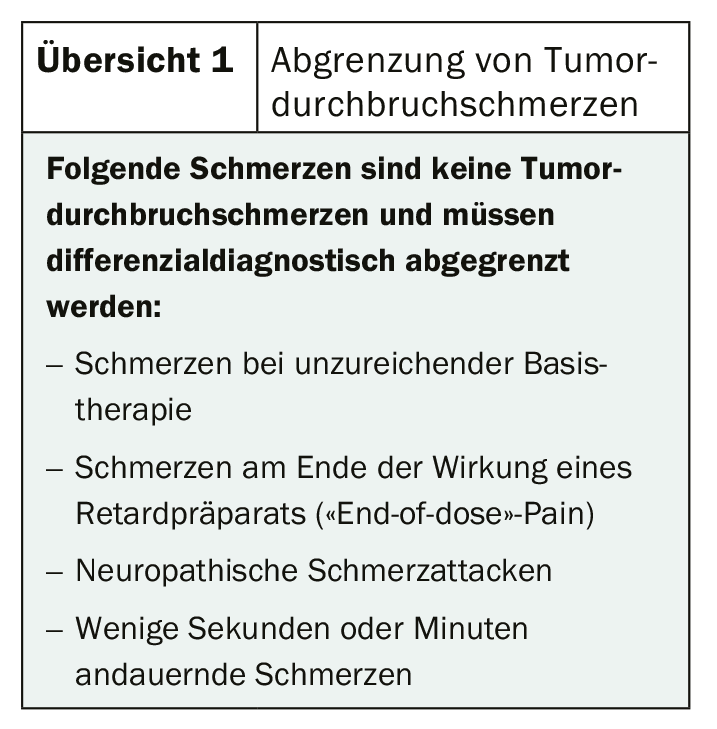

Depending on the stage of disease, up to 95% of all patients with malignancies suffer from tumor-related breakthrough cancer pain (BTcP) [1]. Among inpatient cancer patients, one in two already suffers from this pain, and among hospice patients, 9 out of 10 suffer from it [2–5]. These are defined as “flashes of extremely severe and severe, not infrequently intolerable pain exacerbations occurring in tumor patients spontaneously or in association with a specific predictable or unpredictable trigger despite relatively constant and adequately controlled continuous pain” [1]. Typical are especially the high pain intensity described as unbearable, the sudden onset and the pain peak reached within minutes. The duration of pain is usually 20-30 minutes. The frequency of occurrence varies greatly from patient to patient, but ranges from two to six times daily on average (review 1) [1].

BTcP can be differentiated with regard to their genesis into

- somatic nociceptive (e.g., due to bone metastases or contact with inflamed or infected mucosa).

- Visceral nociceptive (e.g., due to distension or subocclusion of the bowel or acute episodes of tenesmus).

- Neuropathic (due to compression/distortion of a nerve or nerve root or stimulation of a hyperesthetic area).

- mixed pain [6].

Depending on whether the pain occurs as a result of a specific action or event or for no apparent reason, the medication must be adjusted accordingly. For example, in the case of predictable pain, a medication whose maximum effect occurs during the corresponding action can be administered while observing the time window. In the case of spontaneous pain, fast-acting preparations must be used.

Optimized treatment increases quality of life

The ideal therapy for a sudden, severe pain attack involves a rapid onset of action, high analgesic potency, a short duration of action that does not last longer than the pain episode, and ease of use. Opioids, non-opioids and co-analgesics can generally be used. Long-acting opioids are more appropriate as a basic medication because they have a duration of action of 8-12 hours. Short-acting opioids exert their effect after only about 20 minutes. However, this lasts up to four hours and thus significantly longer than the pain attack lasts. The drugs of choice are therefore fast-acting opioids that develop their analgesic effect after only 5-10 minutes for a maximum duration of two hours.

As recommended in current guidelines, fentanyl preparations are primarily used [7–9]. Due to their lipophilicity, they are rapidly absorbed transmucosally or intranasally and quickly cross the blood-brain barrier. As a result, they flood rapidly into the blood, achieve high plasma levels, and have potent analgesic potency about 100 times that of morphine [10,11]. The fast-acting fentanyl can be used in various forms of application. The fastest onset of action of only 5 to 10 minutes is shown by the nasal sprays. For the sublingual and buccal (film) tablets, the onset of action is between 10 and 15 minutes. Oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate takes the longest of all routes of administration, 15 to 30 minutes [6–8].

Literature:

- Everywhere MA: DGS practice guideline tumor-related breakthrough pain version 2.0; 2013; www.DGS-PraxisLeitlinien.de (last accessed 05/10/2020).

- Fortner BV, et al: Description and predictors of direct and indirect costs of pain reported by cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003; 25(1): 9-18.5.

- Portenoy RK, et al: Breakthrough pain in community-dwelling patients with cancer pain and noncancer pain, part 2: impact on function, mood, and quality of life. J Opioid Manag. 2010; 6(2): 109-116.

- Portenoy RK, et al: Breakthrough pain: characteristics and impact in patients with cancer pain. Pain. 1999; 81(1-2): 129-134.

- Greco MT, et al: Epidemiology and pattern of care of breakthrough cancer pain in a longitudinal sample of cancer patients: results from the Cancer Pain Out-come Research Study Group. Clin J Pain. 2011; 27(1): 9-18.

- Vellucci R, et al: What to Do, and What Not to Do, When Diagnosing and Treating Breakthrough Cancer Pain (BTcP): Expert Opinion. Drugs. 2016; 76: 315-330.

- Bornemann-Cimenti H, et al: Fentanyl for the treatment of tumor-related break-through pain. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013; 110(16): 271-277.

- Mercadante S, et al: Breakthrough pain and its treatment: critical review and recommendations of IOPS (Italian Oncologic Pain Survey) expert group. Sup-port Care Cancer. 2016; 24(2): 961-968.

- Davies AN, et al: Breakthrough cancer pain (BTcP) management: a review of in-ternational and national guidelines. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2018; 8(3): 241-249.

- Corli O, Roberto A: Pharmacological and clinical differences among transmu-cosal fentanyl formulations for the treatment of breakthrough cancer pain: a review article. Minerva Anestesiol. 2014; 80(10): 1123-1134.

- Kuip EJM, et al: A review of factors explaining variability in fentanyl pharma-cokinetics; focus on implications for cancer patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017; 83(2): 294-313.

InFo ONcOLOGy & heMATOLOGy

InFo PAIN & GERIATry