The increasing incidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease and the concomitant growing incidence and mortality of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus lead to an increasing health economic importance. Hand in hand with this, one also observes an increase in scientific activity in the area. The aim of this review is to highlight the most important diagnostic and therapeutic innovations in gastroesophageal reflux in a structured manner [1–3].

Symptoms of reflux disease are among the most common diagnoses in outpatient gastroenterology practice. There are relevant differences in the geographic distribution of the incidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). In Asia, the incidence is only about 5%. Although no current figures are available on the incidence in Switzerland, it is likely to be as high as 20%, similar to the United States and the United Kingdom. In Europe, the incidence of reflux disease appears to be increasing; data from 2005 report incidence rates of 10-18%, with more recent data of 9-25%. The main reasons cited are the increasing prevalence of obesity and low infection rates with Helicobacter pylori. Major complications of reflux disease include dysplastic and metaplastic changes in the esophageal mucosa, which increases the risk of developing esophageal cancer.

Meanwhile, symptoms of refractory reflux are the most common indication for gastroscopy. In the United States, at least seven million gastroscopies are performed each year due to reflux symptoms.

Symptoms

Reflux is a physiological process and is defined as the reflux of gastric contents. However, GERD is defined by the interaction of symptoms and damage to the mucosa.

The clinical spectrum of symptoms triggered by gastroesophageal reflux disease ranges from the classic complaints of acid regurgitation, regurgitation of gastric acid, heartburn and stomach burn to extraesophageal manifestations with reflux-associated cough, hoarseness, and nonatopic asthma and globus sensation. Often, the relationship between reflux and symptoms is less clear here, and ORL complaints (chronic sinusitis, “post-nasal drip”) and pneumologic diseases may contribute to the pathogenesis [4].

In so-called functional heartburn, there is no association between symptoms and reflux episodes; this entity is no longer included in the spectrum of GERD.

Reflux disease without endoscopically detectable erosions of the mucosa, so-called non-erosive reflux disease (NERD), is far more common than erosive reflux disease (reflux esophagitis or ERD), accounting for up to 70% of all reflux diseases. This means that in NERD there are symptoms due to reflux of acidic gastric acid, but not mucosal changes that can be grasped endoscopically. This subgroup of reflux disease is much more heterogeneous and can be differentiated by 24-hour pH-metry, as the correlations between symptoms and acid reflux episodes can be established here.

Hypersensitive esophagus is triggered by increased symptom awareness (sensitivity), whether due to acid reflux episodes occurring in physiologic numbers and/or physiologic distension of the esophagus due to nonacid reflux. Similarly, a strong somatization tendency or an anxiety disorder may lead to increased awareness of reflux episodes. Thus, the so-called hypersensitive esophagus can have peripheral and central nervous causes. In these situations, the therapeutic effect of drug acid inhibition is limited. Therapeutically, antidepressants/neuroleptics often need to be used here in addition to PPI to reduce visceral sensitivity.

Reflux lesions are detected endoscopically in 30% of cases. Evidence of reflux erosion is probative of GERD.

Barrett’s esophagus is found endoscopically in up to 10% of cases. Here, the squamous epithelium of the esophagus is replaced by a metaplastic cylindrical epithelium. Pathophysiologically, acid reflux and bile reflux are probably the main causes. Barrett’s esophagus is a precancerous condition, and the incidence of degeneration is approximately 0.1- 3.6%/year [5]. A distinctive feature of Barrett’s esopahgus is the lack of symptoms resp. the disappearance of classic reflux symptoms with progressive mucosal damage. Here, PPI therapy is mainly credited with preventing malignant transformation [6].

Pathogenesis

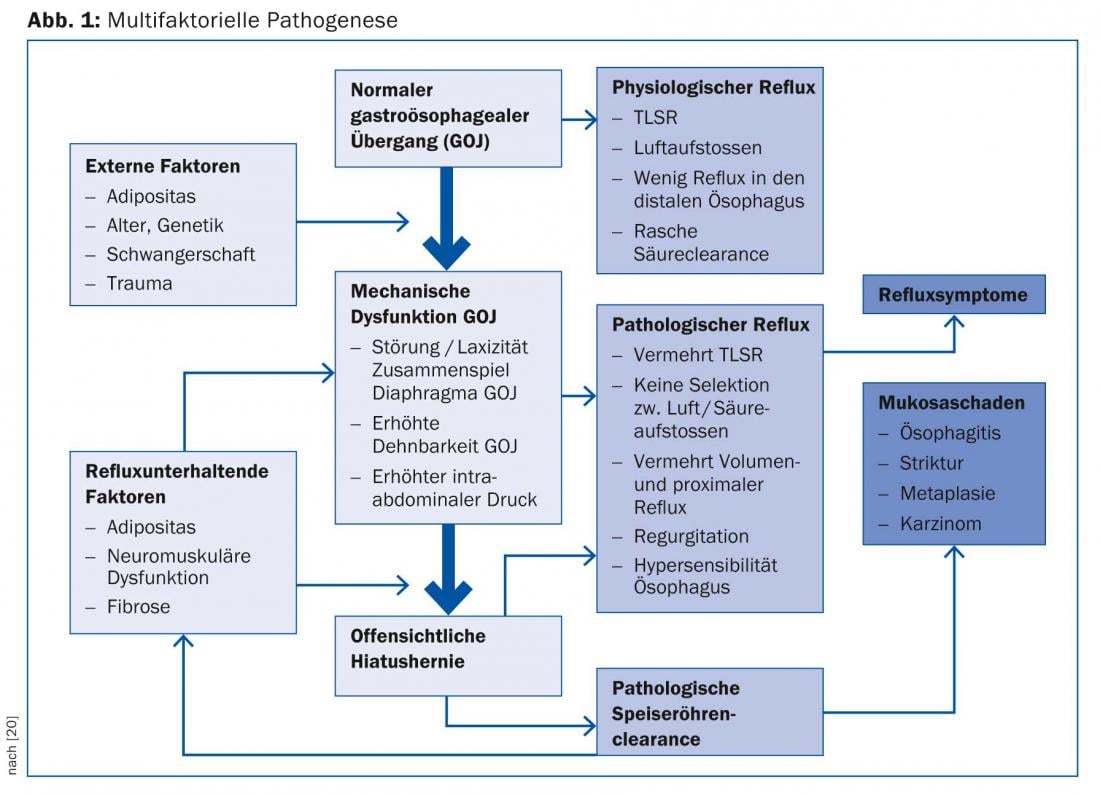

The pathogenesis of GERD is as wide-ranging as the symptoms it causes. Figure 1 is intended to simplify the complex multifactorial pathogenesis and the interaction of structural-anatomical factors (gastroesophageal junction [GOJ], lower esophageal sphincter, hiatal hernia, obesity) and motility (transient relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter [TLSR], sensitivity of the esophageal mucosa).

It shows the progression of reflux disease as a model, where the reflux defense mechanisms are broken down step by step. As the failures of each protective mechanism accumulate, “physiologic reflux” becomes “pathologic reflux,” manifested either by symptoms and/or mucosal damage. Obesity, which is endemic (central) in certain populations, plays an important role in this regard, compromising the strength of the gastroesophageal junction and leading to the development of hiatal hernia over time. Pathogenetic factors include increased intra-abdominal pressure, increased secretion of apokinins, increased transient sphincter relaxation associated with reflux, and increased incidence of Barrett’s esophagus due to metabolic syndrome [7,8]. All of this leads to a two- to threefold increase in esophageal cancer risk in obese patients [9].

Diagnosis

Due to the frequency of symptoms in clinical practice, the question arises whether a specific history with the help of a questionnaire is a safe and cost-effective alternative to endoscopy and would represent a faster route to diagnosis and thus establishment of medicinal acid inhibition using PPI.

According to the guidelines of the DGVS (German Society for Digestive and Metabolic Diseases), heartburn and acid regurgitation are the most specific symptoms of reflux disease. Any other symptoms such as dysphagia, retrosternal pain, and respiratory symptoms may complicate the path to diagnosis [10].

A 2009 study demonstrated that a specifically designed questionnaire (GERDQ) with six questions about reflux symptoms and their severity and frequency diagnosed reflux disease with a high degree of certainty in patients with a score above eight [11]. These data suggest that using a questionnaire, the specificity for diagnosing GERD is very high. Unfortunately, however, the sensitivity of history taking by questionnaire is not very high, which has already been confirmed in older studies [12]. In a recently published study from China in 2000 patients with reflux symptoms examined by the aforementioned questionnaire and endoscopy, it was found that although a large proportion of patients with a higher GERDQ score had reflux esophagitis, on endoscopic follow-up more than one-third of the patients examined with lower scores also had reflux esophagitis. In a smaller percentage of patients, carcinoma was already present despite the absence of alarm symptoms [13]. Jonasson C et al. conclude from his 2012 study that GERD patients without alarm symptoms should be evaluated in a structured manner using questionnaires. This allows costs to be saved without loss of quality and typical GERD patients to be treated efficiently and economically by the general practitioner. An algorithm-based approach also allows identification of patients with low probability of GERD. These patients should be primarily evaluated endoscopically [14].

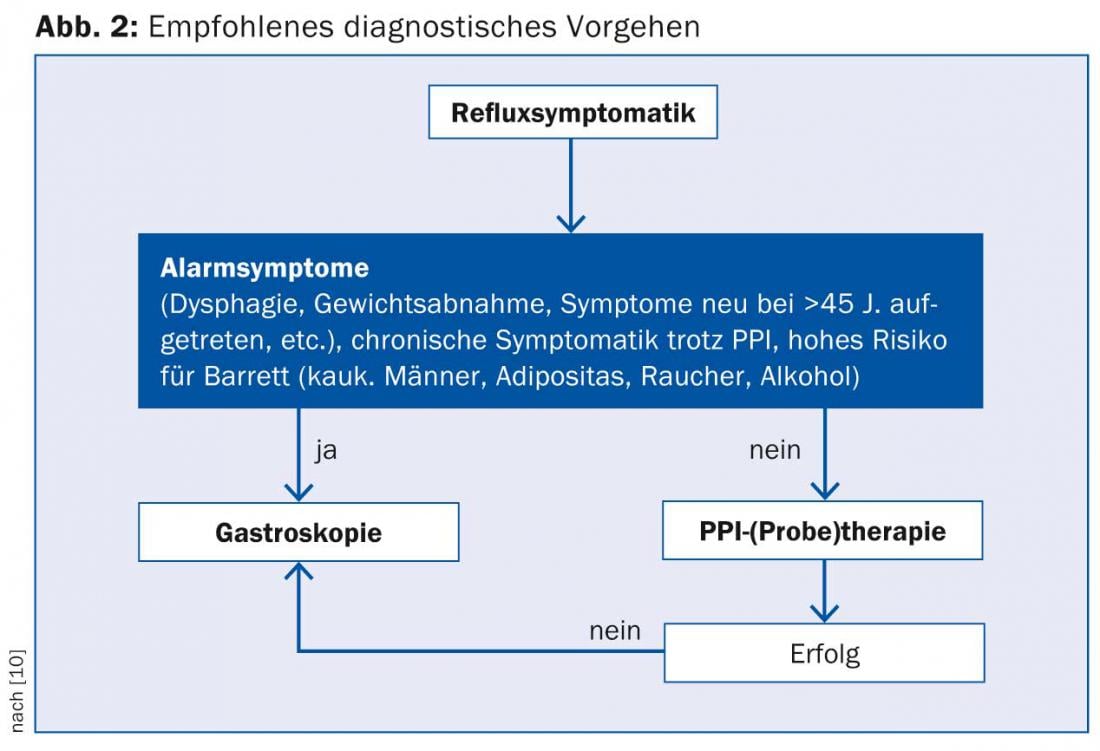

The guidelines of the German Society of Gastroenterology clearly recommend the procedure shown in Figure 2 [10].

Another study in a Chinese collective suggests the potentially important role of early endoscopy in reflux symptoms even in the absence of alarm signs. Nearly 500 patients with reflux symptoms without warning symptoms underwent endoscopy; Barrett’s esophagus was found in nearly 4%, and carcinoma was already present in 1% [15].

Further diagnostics

As mentioned above, in up to 70% of patients with reflux symptoms, no typical esophageal changes are detected and thus only a tentative diagnosis of non-erosive reflux disease can be made (Fig. 1). Since most patients presenting for endoscopy are already treated with acid inhibitors, 24-hour pH-metry is of particular importance in this case. By this method, an objective statement about the presence of pathological reflux, the type of reflux (acidic vs. non-acidic), the duration of reflux episodes, the level of reflux (proximal vs. distal), and the clearance function of the esophagus can be made in cases of suspected NERD. Several studies have shown that the occurrence of ERD or ERD-related NERD, in addition to the number of reflux episodes, the type (acidic vs. non-acidic) as well as the extent of the reflux (proximal/distal) are decisive for the symptomatology. Thus, classic erosive GERD patients present with prolonged and clustered reflux episodes that extend further proximally. This could explain the occurrence of mucosal lesions. Patients with NERD are more likely to have nonacid reflux episodes that still cause symptoms [16,17].

pH metry also plays a crucial role in the diagnosis of hypersensitive esophagus or functional dyspepsia. The distinction is important because different treatment options have significance in these entities than in classic reflux disease. In hypersensitive esophagus, the correlation between symptoms and reflux episodes is particularly important. If a patient has a physiologic number of reflux episodes but feels a high number, the diagnosis of hypersensitive esophagus is obvious.

Therapy

The development of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) has revolutionized the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux, leaving “older” drugs such as H2 blockers with only an additive role in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux. The efficacy of PPI in classic GERD is very good, yet there is a not small group of patients with reflux symptoms who do not respond equally well to PPI. These include the patient groups defined above with hypersensitive esophagus and functional gastric distress. Rarely, a motility disorder such as achalasia may also hide behind functional gastric burning, necessitating further diagnostic testing such as high-resolution esophageal manometry and 24-hour pH-metry in these patients in the absence of a response to therapy [18]. A much lower therapeutic success is also observed for extraesophageal manifestations of reflux disease such as asthma, hoarseness, and cough, as these are not very specific [18–20].

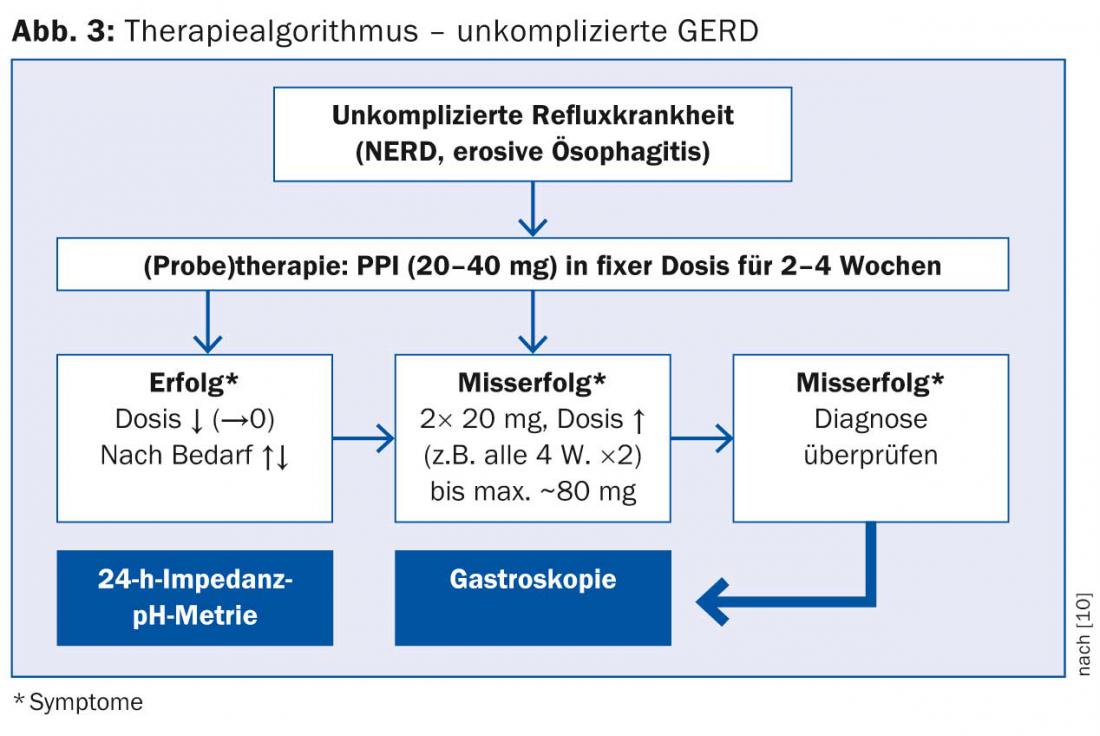

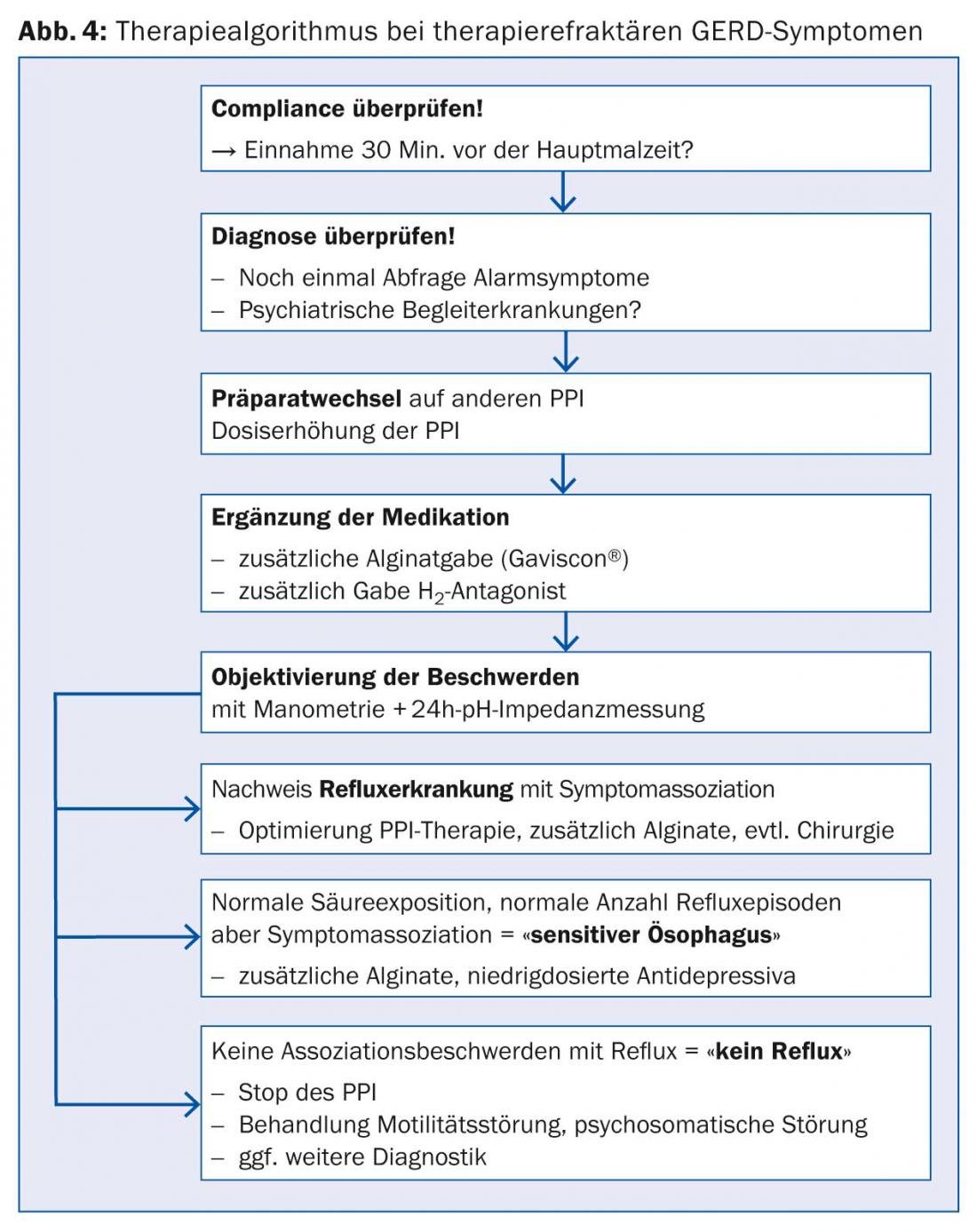

Figures 3 and 4, adapted from the DGVS guidelines, show possible treatment algorithms for uncomplicated and complicated GERD.

It is important to note that discontinuation of PPI should never be done from one day to the next, but in gradual dosing to avoid excessive acid secretion.

With regard to refractory reflux disease, the history of symptoms and intake of acid inhibitors plays a central role. It has been shown that the therapeutic gain for regurgitation was only 20%, whereas up to 40% therapeutic gain can be achieved for retrosternal burning with PPI [19]. By increasing the dose of the PPI from 1× to 2×20 mg/tgl. as well as taking it 30 minutes before a meal, an increased healing rate is achieved [21]. This is due to the half-lives of the individual PPI preparations, which range from 30 to 90 minutes. Also, not all PPIs are equally effective, so switching to either another more acid-suppressing drug such as esomeprazole or a PPI with a different metabolism (cytochrome 450) is recommended if symptoms are refractory [22].

However, the often less than complete absence of symptoms and lack of efficacy of PPIs can be found not only in these details, but also in the fact that (as in Figure 1 shown) acid secretion is not the main factor in the multifactorial pathogenesis of GERD, but the fact that refluxate spreads into the esophagus in pathological amounts.

Since many patients suffer from intermittent symptoms, they require short-acting antacids or alginate preparations.

With Gaviscon®, an alginate preparation, it was shown in a 2009 MRI study that, unlike conventional antacids that sink to the bottom of the stomach, it forms a flow-like mass on the food pulp after the meal, resulting in fewer episodes of reflux [23]. The therapeutic importance as “add on” or “stand alone” therapy for reflux disease is therefore increasing [24,25].

Surgical therapy: when fundoplicatio – when not?

The question of which patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease benefit most from a surgical approach (fundoplicatio) is still controversial. In its general guidelines, the American professional society AGA recommends evaluation of fundoplicatio primarily in patients with low surgical risk who respond well to PPIs but do not want to take them long-term. Other good indications are reflux sequelae that cannot be controlled with medication, such as volume regurgitations and chronic cough with a clear association with proximal reflux. Complications of classic Nissen antireflux surgery include postoperative dysphagia in up to 20% of cases and increased flatulence in up to 50% during short-term follow-up. For these reasons, some esophageal surgeons have recently increasingly favored Toupet surgery (180 – 270°). A randomized trial was able to show that the surgical outcome was equally good in terms of reflux control, but that dysphagia, flatulence, and inability to burp were significantly lower [26]. Patient selection and careful preoperative evaluation by endoscopy, high-resolution manometry, and 24-hour pH-metry, e.g., to exclude esophageal dysfunction, hypersensitivity, or aerophagia, are critical to the success of surgery, in addition to the presence of an experienced surgeon [27].

In contrast, an indication based solely on an allegedly better long-term result is not justified. A study arguing for a prudent approach to the indication for fundoplicatio dates from 2013. She demonstrated, using more than 500 patients randomized to either Nissen fundoplicatio or PPI therapy, that there was no longer a significant difference in overall outcome after five years. Regurgitations were more frequent in the PPI group, whereas more flatulence and bloating occurred in the surgery group[28,29].

Literature:

- El-Serag HB, et al: Update on the epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut 2014; 63: 871-880.

- Peery AF, et al: Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology 2012; 143: 1179-1187 e1-3.

- Holtmann G, Chao J: Functional dyspepsia and functional esophageal disorders. The Gastroenterologist 2013; 8: 385-392.

- Fox M, Forgacs I: Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. BMJ 2006; 332: 88-93.

- Spechler SJ, Souza RF: Barrett’s esophagus. New England Journal of Medicine 2014; 371: 836-845.

- Fox M, Schwizer W: Making sense of esophageal contents. Gut 2008; 57: 435-438.

- Wu J, et al: Obesity is associated with increased transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. Gastroenterology 2007; 132: 883-889.

- Ryan A, et al: Barrett’s esophagus: prevalence of central adiposity, metabolic syndrome, and a proinflammatory state. Annals of surgery 2008; 247: 909-915.

- Ryan A, et al: Obesity, metabolic syndrome and esophageal adenocarcinoma: epidemiology, etiology and new targets. Cancer Epidemiology 2011; 35: 309-319.

- Koop H, et al: Consensus conference of the DGVS on gastroesophageal reflux. Journal of Gastroenterology 2005; 43: 163-164.

- Jones R, et al: Development of the GerdQ, a tool for the diagnosis and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 30: 1030-1038.

- Dent J, et al: Accuracy of the diagnosis of GORD by questionnaire, physicians and a trial of proton pump inhibitor treatment: the Diamond Study. Gut 2010; 59: 714-721.

- Bai Y, et al: Gastroesophageal reflux disease questionnaire (GerdQ) in real-world practice: a national multicenter survey on 8065 patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 28: 626-631.

- Jonasson C, et al: Randomised clinical trial: a comparison between a GerdQ-based algorithm and an endoscopy-based approach for the diagnosis and initial treatment of GERD. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 2012; 35: 1290-1300.

- Peng S, et al: Prompt upper endoscopy is an appropriate initial management in uninvestigated chinese patients with typical reflux symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105: 1947-1952.

- Savarino E, et al: Characteristics of reflux episodes and symptom association in patients with erosive esophagitis and nonerosive reflux disease: study using combined impedance-pH off therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105: 1053-1061.

- Bredenoord AJ, Hemmink GJM, Smout AJPM: Relationship between gastro-oesophageal reflux pattern and severity of mucosal damage. Neurogastroenterology & Motility 2009; 21: 807-812.

- Kessing B, Bredenoord A, Smout AJPM: Erroneous diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease in achalasia. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology 2011; 9: 1020-1024.

- Kahrilas PJ, Howden CW, Hughes N: Response of regurgitation to proton pump inhibitor therapy in clinical trials of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 1419-1425; quiz 1426.

- Boeckxstaens G, et al: Symptomatic reflux disease: the present, the past and the future. Gut 2014; 63: 1185-1193.

- Kinoshita Y, Hongo M, Japan TSG: Efficacy of twice-daily rabeprazole for reflux esophagitis patients refractory to standard once-daily administration of PPI: the Japan-based TWICE study. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 522-530.

- Miner P, et al: Gastric acid control with esomeprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole: a five-way crossover study. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98: 2616-2620.

- Sweis R, et al: Post-prandial reflux suppression by a raft-forming alginate (Gaviscon Advance) compared to a simple antacid documented by magnetic resonance imaging and pH-impedance monitoring: mechanistic assessment in healthy volunteers and randomised, controlled, double-blind study in reflux patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013 Jun; 37(11): 1093-1102.

- Thomas E, et al: Randomised clinical trial: relief of upper gastrointestinal symptoms by an acid pocket-targeting alginate-antacid (Gaviscon Double Action) – a double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot study in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 2014; 39: 595-602.

- Kahrilas P, et al: The acid pocket: a target for treatment in reflux disease? The American journal of gastroenterology 2013; 108: 1058-1064.

- Broeders J, et al: Five-year outcome after laparoscopic anterior partial versus Nissen fundoplication: four randomized trials. Annals of surgery 2012; 255: 637-642.

- Falk G, Fennerty MB, Rothstein R: AGA Institute medical position statement on the use of endoscopic therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 2006; 131: 1313-1314.

- Grant AM, et al: Minimal access surgery compared with medical management for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: five year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial (REFLUX). BMJ 2013; 346: f1908.

- Galmiche JP, et al: Laparoscopic antireflux surgery vs esomeprazole treatment for chronic GERD: the LOTUS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2011; 305: 1969-1977.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(9): 26-30