Parkinson’s patients often have muscle weakness, which is exacerbated by lack of exercise. This increases the risk of osteoporosis, falls and fractures. Physical activity and exercise can help improve walking ability and balance in people with Parkinson’s disease and also reduces mortality. Endurance sports such as Nordic walking, swimming, dancing or cycling (also on the exercise bike) are particularly useful.

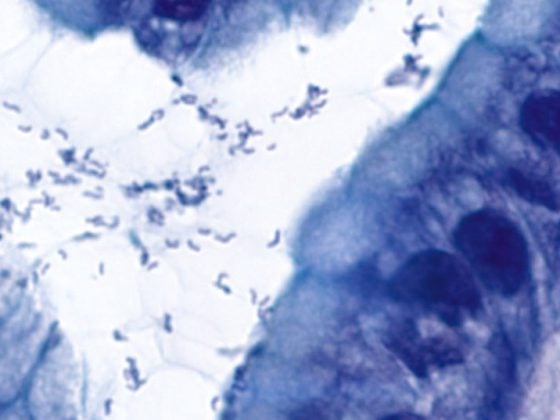

Idiopathic Parkinson’s syndrome (IPS) is a neurodegenerative, progressive disease defined clinically by the four cardinal symptoms of hypokinesia, rigor, tremor, and postural instability. Age is the main risk factor of IPS, which has a prevalence of 0.3% in the general population and 1-2% in those over 65 years of age. The neuropathological correlate of motor symptoms is the destruction of dopamine-producing cells in the substantia nigra in the brainstem. This finding was the basis of dopaminergic therapy with first the dopamine precursor L-dopa, and later the postsynaptically acting dopamine agonists. These drugs have a symptomatic effect; no disease-preventing or disease-delaying, i.e., neuroprotective, effect of dopaminergics has been demonstrated to date.

With progressive disease under therapy with L-dopa, loss of effect and motor complications occur (dyskinesias, on-off phenomenon). The dopamine agonists are less effective than L-dopa; they can reduce dyskinesias when used in the early stages but have neuropsychiatric side effects in the elderly and with longer disease duration.

Non-motor symptoms

In addition to motor symptoms, IPS also presents with a number of non-motor symptoms (sleep disturbances, anxiety, depression, constipation, hyposmia, hallucinations, dementia). These are due to degeneration of structures other than the substantia nigra and respond less well to dopaminergic medication, if at all. It is precisely these non-motor symptoms that are judged by those affected to be particularly impairing in terms of quality of life. Sleep disturbances, depression and anxiety often occur before motor symptoms. Hallucinations and dementia are often causes for nursing home admission in advanced stages of the disease.

This plethora of symptoms, which increase in severity over time, creates a complex picture that affects quality of life and can be viewed as premature aging, with a decline in both motor and cognitive functions.

What can physical activity do?

Intuitively, physical activity is thought to be an important therapeutic approach in IPS, even more so given the aforementioned problems of pharmacotherapy. In particular, the questions of whether exercise and sport have a preventive or neuroprotective influence and what type of physical activity is useful and to what extent are of concern to patients and practitioners from various disciplines.

Muscle weakness, lack of exercise and osteoporosis

Parkinson’s disease patients exhibit muscle weakness compared to healthy individuals, characterized by decreased selectivity of muscle recruitment and slowing [1]. When dopaminergic medication is interrupted (off-state), muscle strength is decreased compared to the state with medication (on-state). Neurophysiological studies suggest that the globus pallidus internus (the target area of dopaminergic neurons from the substantia nigra) exerts a focusing effect on movement and an inhibition of agonists during movements [2]. In the EEG, IPS patients can be shown to have decreased activity over premotor brain areas responsible for movement planning [2]. This centrally induced bradykinesis can cause Parkinson’s patients to move less and less as the disease progresses.

Decrease in physical activity increases the risk of osteoporosis in IPS [3]. Bone density of the femur is decreased in PD patients, resulting in a threefold increase in the incidence of hip fractures compared to healthy individuals [2]. Also, the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency is significantly higher in IPS [4]. Therapy studies with bisphosphonates and vitamin D substitution have demonstrated an increase in bone density and a reduction in hip fracture risk after a treatment period of two years [5]. For the therapy of osteoporosis as an additional risk factor for fractures in falls, medication with bisphosphonates and vitamin D as well as physical activity is recommended in Parkinson’s patients.

Physical activity reduces the risk of IPS

Prospective studies have shown that physical activity in adulthood has a protective effect on the risk of developing PD later in life [6–8]. It must be taken into account that a reverse causality cannot be excluded by these studies: Parkinson’s patients could already be physically less active in the premotor phase due to movement-avoiding behavior [6]. Physical activity also reduces mortality risk in PD patients [9].

Is physical activity neuroprotective?

Animal work has demonstrated stimulation of cerebral dopamine synthesis, increased levels of neurotrophic factors that promote plasticity, and a significant increase in dopaminergic neurons and axons in the nigrostriatal system with increased physical activity [6]. Regarding data in humans, the number of good quality studies that have investigated the efficacy of muscle strengthening training in IPS is small, with a large heterogeneity in the therapeutic protocols applied. Complicating the evaluation of these studies with respect to a possible neuroprotective effect are medication changes during the course of the study, too short a study duration compared with slow disease progression, and the lack of a biomarker for disease progression.

Although these limitations exist, several authors conclude that despite the lack of evidence for a delay in disease progression by physical activity from the totality of all data, a neuroprotective effect of physical activity in IPS seems plausible [2,6,7].

Recommendations for the intensity of training

There is no consensus in the literature regarding the intensity of physical activity. Ahlskog calls for activities that increase heart rate and thus oxygen consumption to be performed for a sufficient duration (20-30 minutes), on a regular basis, and for a longer period of time [6]. Examples cited include rapid walking, jogging, bicycling, intense dancing and swimming, as well as activities such as vacuuming or shoveling. Falvo and coworkers suggest therapeutically planned and supervised strength training, which should take place at a frequency of initially two to three times, and in the course four to five times a week [2]. The program consists of concentric and eccentric exercises, each with 8-12 repetitions and sufficient breaks between sessions.

Symptomatic exercise therapy/physiotherapy

Physiotherapy is usually used for Parkinson’s patients in cases of manifest motor problems such as gait disorders, blockages, balance problems, posture disorders, and for advice and instruction regarding assistive devices. Important is an initial problem analysis with assessment of the relevant functions and a definition of the therapy goal, so that an improvement relevant to everyday life can be achieved for the problem and the individual needs of the patient. In the example of balance problems with increased falls, an analysis of the cause of the fall, an assessment by means of, for example, the Berg Balance Scale and, if necessary, a gait analysis should be carried out. From this, the measures to be taken can be derived, e.g. specific gait training and muscle building, if necessary medication adjustment or use of aids. If freezing is identified as the cause of a fall, instruction of possible strategies may be helpful (counting off, laser stick, metronome, or similar). On the other hand, in cases of falls caused by orthostasis, a review of medication with reduction of antihypertensive agents, use of antihypotensives, and compression stockings (class II) may be beneficial. In the case of a pronounced reduction in postural control, compensatory strategies are usually less successful, and the focus there is often on the provision of aids (rollator, hip protectors or wheelchair).

A Cochrane meta-analysis published in 2013 showed a small but significant effect of physiotherapy in IPS compared with placebo or no therapy, relevant to everyday life [10]. The parameters tested were walking ability (speed, 6-minute walk test, Freezing of gait Questionnaire, Timed up and go test), balance (Functional Reach Test, Berg Balance Scale), and disability assessment by the treating physician using the UPDRS (Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale). In contrast, no differences were found regarding frequency of falls and assessment of quality of life by patients using the PDQ-39 questionnaire.

What types of exercise and sports are useful?

In particular, IPS patients who have not previously been physically active should be counseled and motivated to engage in a sufficiently activating type of exercise appropriate to them at the frequency of at least three to four times a week for 30 minutes. In addition to an individual training program, as usually instructed in physiotherapy, jogging, Nordic walking, swimming and cycling (on the home trainer at best) are favorable.

Li and coworkers showed in a study published in 2012 that compared with strength training and stretching exercises, tai chi improved walking ability and balance and decreased the incidence of falls [11]. Parkinson Switzerland offers Tai Chi courses at various locations.

An alternative form of exercise, also offered by Parkinson Switzerland, is tango classes. In one study, patients who danced tango for one hour weekly for 12 months showed significant improvement in walking ability and balance compared with non-active patients [12].

Take-Home Messages

- Adults who are regularly physically active,

- have a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s disease.

- Regular, physical activity reduces mortality in Parkinson’s disease patients.

- There is evidence for a neuroprotective effect of physical activity from animal models of Parkinson’s disease.

- A Cochrane meta-analysis demonstrated a significant effect on walking ability and balance for physiotherapy in Parkinson’s disease compared with placebo or no therapy.

- Physical activity should be sufficiently long (30 minutes) and frequent (three to five times a week). In addition to jogging, Nordic walking, swimming and cycling, tai chi and tango can also be considered.

Heiner Brunnschweiler, M.D.

Literature:

- Berardelli A, et al: Pathophysiology of bradykinesia in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2001; 124: 2131-2146.

- Falvo MJ, Schilling BK, Earhart GM: Parkinson’s disease and resistive exercise: rationale, review, and recommendations. MOV Disord 2008; 23: 1-11.

- Vaserman N: Parkinson’s Disease and osteoporosis. Joint Bone Spine 2005; 72: 484-488.

- Sato Y, et al: High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and reduced bone mass in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 1997; 49: 1273-1278.

- Sato Y, et al: Risedronate and ergocalciferol prevent hip fracture in elderly men with Parkinson disease. Neurology 2007; 68: 911-915.

- Ahlskog JE: Does vigorous exercise have a neuroprotective effect in Parkinson disease? Neurology 2011; 77: 288-294.

- Grazina R, Massano J: Physical exercise and Parkinson’s disease: influence on symptoms, disease course and prevention. Rev Neurosci 2013; 24(2): 139-152.

- Xu Q, et al: Physical activities and future risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology 2010; 75: 341-348.

- Kuroda K, et al: Effect of physical exercise on mortality in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand 1992; 86: 55-59.

- Tomlinson CL, et al: Physiotherapy versus placebo or no intervention in Parkinson’s disease (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013. issue 9. art. No. CD 002817.

- Li F, et al: Tai chi and postural stability in patients with Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med 2012; 366(6): 511-519.

- Duncan RP, et al: Randomized controlled trial of community-based dancing to modify disease progression in Parkinson disease. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2012; 26(2): 132-143.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2015; 13(1): 11-14.