Patients with biologic valve replacements have a higher likelihood of reoperation but a smaller likelihood of major bleeding compared with patients with mechanical aortic valve prostheses. Current studies show no survival benefit at 15 years in patients with mechanical resp. biological aortic valve prostheses. The choice for a biological or mechanical valve prosthesis should be based on other considerations apart from the patient’s age, such as patient compliance, contraindication to lifelong anticoagulation, and risks of morbidity. TAVI should currently be considered only in patients with high operative risk and clear contraindications to open cardiac surgery. The decision to perform TAVI or open surgery in borderline patients should be made by an interdisciplinary cardiac team that includes cardiologists and cardiac surgeons and should be performed exclusively at centers that have an integrated cardiac surgery department.

“What mankind can dream, research and technology can achieve.” This quote from Walton E. Lillehei, a pioneer of modern heart surgery, from the 1950s was more than just words – it became the philosophy for a number of young scientists. After more than 50 years of experience with surgical heart valve implants, no single valve type, mechanical or biological, has been established as suitable for all indications requiring surgical replacement of the aortic valve [1]. Today, the surgeon must choose from a plethora of different heart valves (mechanical, stented, “stentless” and “sutureless”, homografts), and this choice has been steadily expanding over the past decade, especially in the area of biological, catheter-based heart valves.

Frequent intervention with different approaches

With more than 19 000 interventions in 2013, operations on the aortic valve are among the most common procedures performed at cardiac surgery centers in Germany, as in most other Western countries. More than 9000 interventions were performed as catheter-assisted aortic valve implantation (TAVI), according to the latest performance data from the German Society for Thoracic, Cardiovascular and Vascular Surgery (DGTHG). A surgical mechanical heart valve (MHV) is mainly considered in patients <60 years of age, as there is no degeneration of the valve material. In contrast, the surgical biological heart valves, made from porcine, equine, or bovine pericardium, do not require permanent oral anticoagulation, but degeneration of the biological valve prosthesis is evident after 10-20 years, depending on the age of the patient at the time of implantation [2].

A European survey showed that a substantial number of patients do not receive cardiac surgery for a wide variety of reasons [3]. These figures have also been confirmed for American conditions: Svensson reported that %–60% of patients with high-grade aortic valve stenosis cannot be considered for surgical valve replacement without risk because of advanced age and severe concomitant diseases [4]. Treatment of multimorbid patients (EuroSCORE >20%; STS score >10%) whose concomitant diseases such as high-grade renal failure or heart failure (NYHA IV) are too high a risk for conventional surgical valve replacement can be treated with less invasive procedures under certain conditions [4–9] However, there are also certain new risks and clear indication guidelines [10].

The first percutaneous implantation of a foldable aortic valve stent in a patient was performed in 2002 by Alain Cribier [11]. The technique is based on the procedure of balloon valvuloplasty of highly stenosed aortic valves with subsequent implantation of a valve-bearing stent. Today, there are numerous access routes for this procedure: transaortic, transapical, transfemoral, transaxillary, and via the carotid artery.

Operation indication

According to the current guidelines of the European Associations for Cardiac Surgery (EACTS) and Cardiology (ESC), open surgical aortic valve replacement with sternotomy and with heart-lung machine is still the gold standard for the treatment of high-grade aortic valve stenosis [10,12].

The indication for surgical therapy is given when the valve orifice area is less than 1 cm2, when the pressure gradient is ≥50 mmHg, and when the flow velocity across the aortic valve measured by echocardiography is >4 m/s [13]. The diagnosis of low-flow, low-gradient aortic valve stenosis with normal left ventricular contractility requires very special attention because the data on pathogenesis as well as survival after surgery are very limited. In these patients, surgery should be performed only when appropriate clinical symptoms are present, diagnostic testing confirms significant valvular stenosis, and a normal left ventricular ejection fraction is present (>55%) [10].

Catheter-assisted aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is indicated in patients with severe symptomatic aortic valve stenosis who, after consultation with the heart team, are not suitable for surgical aortic valve replacement, in whom improvement in quality of life is likely in view of comorbidities, and in whom a life expectancy of more than one year can be predicted [10].

Risk stratification in surgical valve replacement.

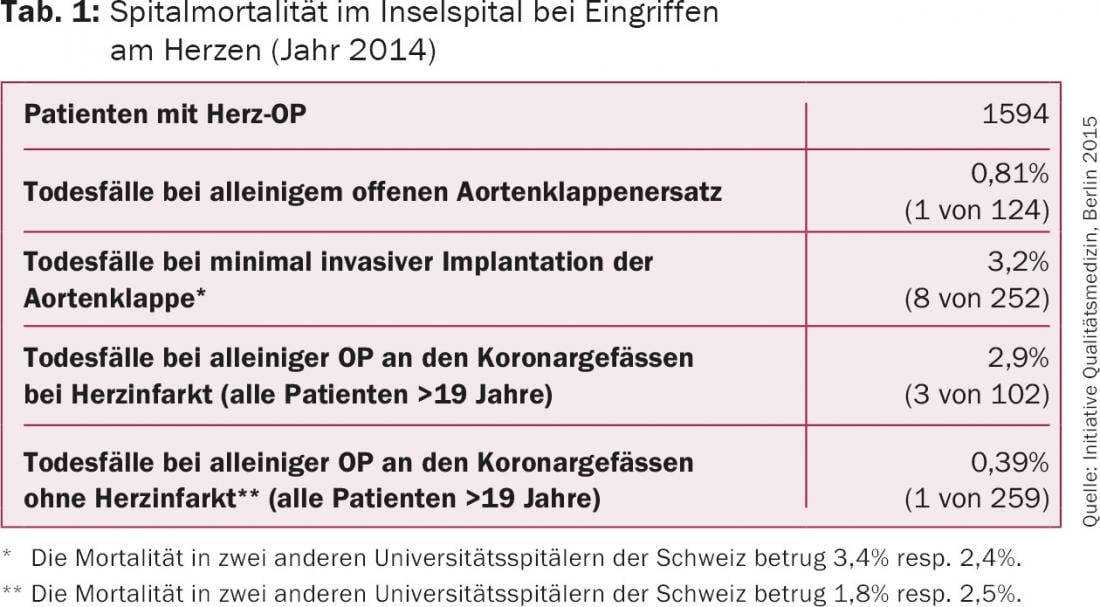

According to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database, the 30-day mortality for isolated surgical aortic valve replacement is 2.6-3%–3,3% [14]. Patients younger than 70 years show a mortality of%–3%, in older patient collectives %–8%. In our hospital, the 30-day mortality rate has been significantly <1.5% in recent years and was less than one percent in 2014 (Table 1).

Mechanical vs. biological heart valves

In a retrospective study by Chiang of more than 11000 patients, 34.5% of patients received a biological aortic valve and 65.5% received a mechanical aortic valve [15]. A standardized method was used to create 1000 comparable pairs (propensity matching), thus age and baseline comorbidities collected were evenly distributed between the two groups. Patients with a biological valve were older on average and more likely to have diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular disease, coagulation disorders, liver disease, or cancer than those patients implanted with a mechanical prosthesis [15]. There was no difference in long-term survival between the groups: 15-year survival was 60.6% after implantation of a bioprosthesis and 62.1% after implantation of a mechanical prosthesis. No difference was also found in the rate of cerebrovascular events (cumulative 15-year incidence in the patient group with bioprosthesis 7.7%, with mechanical valve 8.6%).

Biological prostheses were associated with a significantly higher reoperation rate: The cumulative incidence of reoperation 15 years after implantation of a biological valve was 12.1% vs. 6.9% after implantation of a mechanical valve.

Mechanical prostheses were associated with a significantly higher rate of major bleeding because of the need for oral anticoagulation: The 15-year cumulative incidence of major bleeding was 6.6% in the biological valve group and 13% in the mechanical valve group.

Transcatheter heart valve replacement (TAVI)

In recent years, for example, in Germany, there has been a surge in TAVI (144 in 2007, 9147 in 2013), whereas the number of cardiac surgery procedures has remained relatively stable over the same period (8622 in 2007, 7048 in 2013) [16]. Unfortunately, several clinical studies showed a similar, if not higher, complication rate for cerebrovascular events, cardiac arrhythmias, and paravalvular leakage after application of this technology. The rate of cerebrovascular complications after TAVI is 1-5% according to recent studies. The need for pacemaker implantation depends on the valve type and is 7% for balloon-expandable prosthetic valves; up to 40% for self-expandable prosthetic valves [16,17]. Paravalvular leakage is a common problem when using this technology [9]. The rate of moderate to severe paravalvular leakage ranges from 6% to 21%, depending on the type of valve selected [18].

The results of the PARTNER trial (The Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valve) demonstrated that even moderate paravalvular leakage leads to a significant increase in mortality [19]. The recognized problem of paravalvular leakage with the use of transcatheter valves may become the “Achilles’ heel” of this technology because of increased mortality over the long-term [18].

In a study by Reinöhl, a total of 88 573 aortic valves were replaced over a six-year study period (TAVI: 32 581, surgical aortic valves: 55 992). Patients in the TAVI group were older on average compared with the surgical group (81 ± 6.1 vs. 70.2 ± 10 years). According to the logistic EuroSCOREs (European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation), the operative risk was 22.4% for patients in the TAVI group and 6.3% for the surgical group [15]. The 30-day mortality in the two groups showed a decrease over the study period (2007-2013) from 13.2% to 5.4% for the TAVI group and from 3.8% to 2.2% for the surgical aortic valve replacement group [16]. Due to life-threatening complications such as annulus rupture, coronary artery obstruction, aortic dissection, left ventricular injury, or valve dislocation, up to 4% of TAVI patients require emergency cardiac surgery [9,11]. In such situations, which are associated with very high mortality, patients usually have a chance of survival only in centers with an incorporated cardiac surgery department. Therefore, these interventions should only be performed in hospitals that meet the best quality standards for both cardiology and cardiac surgery.

Literature:

- DeWall RA, Qasim N, Carr L: Evolution of mechanical heart valves. Ann Thorac Surg 2000; 69: 1612-1621.

- Kouchoukos NT, et al: Kirklin/Barratt-Boyes Cardiac Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2012.

- Iung B, et al: A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: The Euro Heart Survey on valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2003; 24(13): 1231-1243.

- Svensson LG, et al: United States feasibility study of transcatheter insertion of a stented aortic valve by the left ventricular apex. Ann Thorac Surg 2008; 86: 46-54, discussion 54-55.

- Contaldi C, et al: Percutaneous treatment of patients with heart diseases: selection, guidance and follow-up. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2012; 10: 16.

- Sehatzadeh S, et al: Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) for treatment of aortic valve stenosis: an evidence-based analysis (part B). Ont Health Technol Assess Ser 2012; 12: 1-62.

- Sinning JM, et al: Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the evidence. Heart 2012; 98 Suppl 4: iv65-72.

- Panico C, et al: Predictors of mortality in patients undergoing percutaneous aortic valve implantation. Minerva Cardioangiol 2012; 60: 561-571.

- Popma JJ, et al: Transcatheter aortic valve replacement using a self-expanding bioprosthesis in patients with severe aortic stenosis at extreme risk for surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63: 1972-1981.

- Vahanian A, et al: Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012): The Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 2451-2496.

- Cribier A, et al: Percutaneous transcatheter implantation of an aortic valve prosthesis for calcific aortic stenosis: first human case description. Circulation 2002; 106: 3006-3008.

- Beckmann A, et al: The German Aortic Valve Registry (GARY): a nationwide registry for patients undergoing invasive therapy for severe aortic valve stenosis. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012; 60: 319-325.

- Schmid C: Guide to adult cardiac surgery. Springer, 2006.

- D’Agostino RS, et al: The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database: 2016 Update on Outcomes and Quality. Ann Thorac Surg 2016; 101: 24-32.

- Chiang YP, et al: Survival and long-term outcomes following bioprosthetic vs mechanical aortic valve replacement in patients aged 50 to 69 years. JAMA 2014; 312: 1323-1329.

- Reinöhl J, et al: Effect of Availability of Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement on Clinical Practice. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 2438-2447.

- Leon MB, et al: Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 1597-1607.

- Généreux P, et al: Paravalvular leak after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: the new Achilles’ heel? A comprehensive review of the literature. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61: 1125-1136.

- Kodali SK, et al: Two-year outcomes after transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1686-1695.

CARDIOVASC 2016; 15(1): 16-21