The duty to maintain medical devices is incumbent on the person who uses them on third parties. Violations of the maintenance obligation are sanctioned as misdemeanors by Swissmedic. Physician advertising must be objective, meet a public need, and not be misleading or intrusive. Information that primarily serves an end in itself is inadmissible.

The following questions at the interface of medicine and law are devoted to three common aspects: The maintenance obligation and defects of medical devices, questions regarding the permissibility of advertising for physicians and drugs or treatments, and questions regarding the assumption of drug and treatment costs by health insurance companies.

Who is responsible for maintenance?

According to Art. 4 para. 1 lit. b HMG, medical devices are “…products, including instruments, apparatus, in vitro diagnostics, software and other articles or substances intended or advertised for medical use, the principal effect of which is not achieved by a medicinal product”.

The duty to maintain medical devices is incumbent on the person who uses the medical device on third parties [1]. Maintenance must be carried out in accordance with the instructions of the initial distributor. It is advisable to record the medical devices in a register that records the clear identification of the devices, the type and frequency of maintenance, and the persons and bodies responsible for maintenance. In addition to this list, it is helpful to keep a so-called equipment journal in which the planned maintenance measures, the defects or malfunctions, measures taken and the result of the maintenance are listed [2].

This is the only way to provide complete proof at a later date that the maintenance obligation has been fulfilled in accordance with the law. Violations of the maintenance obligation are sanctioned as misdemeanors by Swissmedic [3].

Does a practice need a laser safety officer?

If treatments with class 3B or 4 lasers are performed in a practice, a laser safety officer must be appointed by the management. The laser officer must draw up a safety concept and inform all persons working with lasers of the corresponding classes about the dangers as well as the correct handling of the devices [4]. For evidence purposes, it is advisable to draw up specifications for the laser safety officer and to document the safety concept [5].

How to proceed in case of a defective medical device?

The Buyer has the obligation to inspect the product upon acceptance and to immediately complain to the Contracting Party about any defects that may exist. A notice of defects must contain the following: a description of the defect as substantiated as possible and the submission that the item is recognized as not conforming to the contract as a result of the defect and that the other party is liable for it [6]. It is recommended to send a notice of defects to the Contracting Party by registered mail for evidence purposes and to keep a copy of the letter as well as the proof of delivery from the Post Office. Shipment tracking can only be accessed on the Swiss Post website for a certain period of time. After that the data will be deleted. It therefore makes sense to also archive the electronic shipment tracking in printed form or electronically as a PDF after delivery. The burden of proof for the timeliness and the existence of the defects at the time of the conclusion of the contract lies with the buyer. Defects that can only be detected at a later point in time (so-called hidden defects) must also be objected to immediately after discovery with a notice of defect. In any case, the notification of defects must be made immediately. According to case law, this usually means a complaint within two to three days or, depending on the defect, within seven days after inspection of the item or discovery of the defect [7]. Without an immediate notice of defect, all rights of the purchaser with respect to defects shall be forfeited [8].

What is unlawful advertising and what are the consequences?

The MedBG requires advertising physicians to be objective, in line with a public need, and neither misleading nor intrusive [9].

If a medical advertisement does not meet these criteria, it is a violation of professional duties, which is sanctioned with a reprimand, a warning or a fine of up to CHF 20,000 or even a ban from practicing medicine by the cantonal supervisory authority [10]. The Code of Professional Conduct may be consulted for the interpretation of professional duties [11]. However, a violation of the FMH Code of Professional Conduct does not necessarily also lead to disciplinary consequences under the Medical Profession Act. This is because the code of conduct represents association law, which means that it can only apply to association members – in contrast to the professional duties, which represent public law and must be complied with by all professionals. The Code of Professional Conduct provides for sanctions such as a reprimand, a fine of up to CHF 50,000, suspension of membership for a certain period of time, expulsion from the society/FMH, publication in the publication organs of the cantonal medical societies, the VSAO, the VLSS or FMH, notification of the competent health directorate or appropriate health insurance bodies, and the appointment of a supervisor. The individual sanctions may also be linked or combined [12].

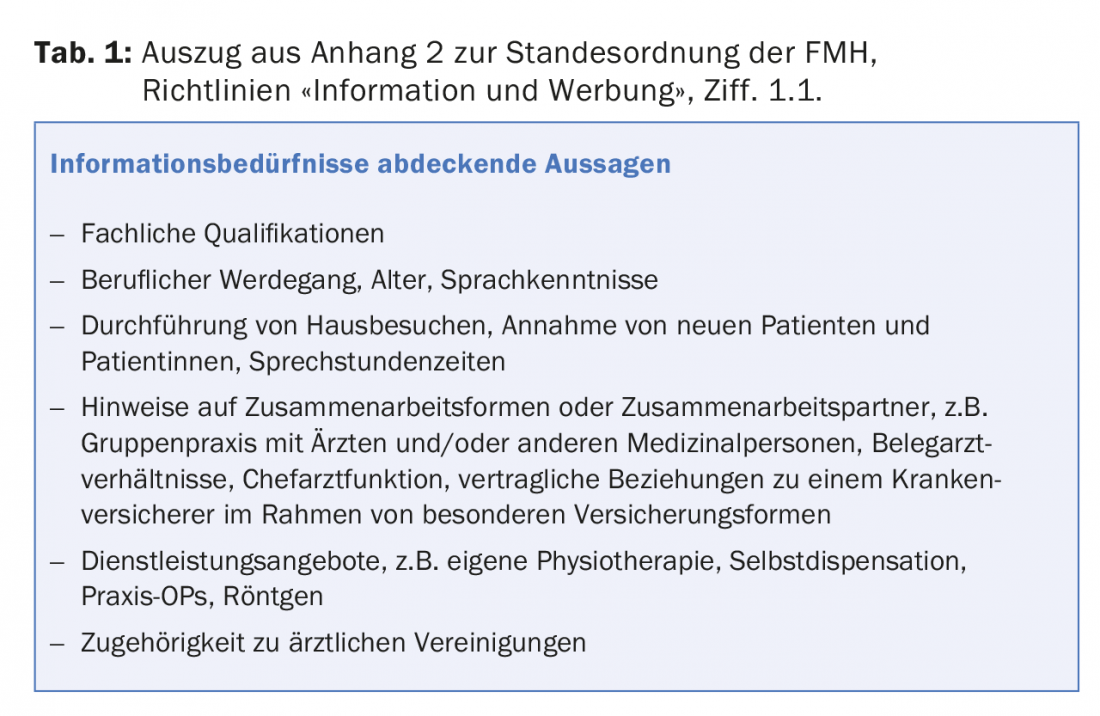

The Professional Code of Conduct of the FMH defines permissible information as follows: Female physicians may “[…] disclose their professional qualifications as well as all other information necessary for patient and patient or colleague in a restrained and unobtrusive manner”. [13] and shall refrain ” […] in their medical activities from any advertising that is unobjective, based on untrue allegations, or detrimental to the reputation of the medical profession […] “. [14] and to work to ensure “[…] that a third party does not engage in unlawful advertising for their direct or indirect benefit”. [15].

Information is considered necessary if its knowledge makes it easier for the patient to choose a suitable physician [16]. The “Information and Advertising” guidelines (Tab. 1) explicitly mention various pieces of information that are considered necessary.

Information that, for example, serves the physician’s self-promotion and primarily an advertising purpose is inadmissible [17]. Announcement of information in the form of mass mailings such as postal mailings or electronic media to the population is not permitted [18]. From the point of view of professional ethics, it would probably be problematic if a doctor were to make general information about her practice known to the general public via a public Twitter account [19]. Under the Rules of Professional Conduct, it would also not be permissible to offer treatment on digital shopping platforms, if applicable.

Furthermore, under the Therapeutic Products Act, advertising to the public for prescription drugs is not permitted [20]. Already reports which advertise about a disease and the indication of a medicinal product – without mentioning its name – can be qualified as inadmissible advertising to the public if the clinical picture is inseparably connected with the remedy so that one term inevitably leads to the conclusion of the other [21]. The decisive criterion is the overall impression of how the audience is objectively addressed [22]. Unauthorized advertising of medicinal products is sanctioned by Swissmedic as an infringement [23].

What is permissible advertising of treatments with botulinum toxin?

The advertising regulations under therapeutic product law are strict in the case of botulinum toxin. For example, a website that advertised the possible uses and effects of botulinum toxin and linked to press and advertising texts was qualified as inadmissible advertising to the public. The website operator was accused of promoting botulinum toxin as a fascinating active ingredient and off-label use as a “modern and particularly effective” method, and that the side effects did not correspond to the corresponding drug information, thus playing down the active ingredient in order to persuade customers to undergo wrinkle treatment with products containing the active ingredient botulinum toxin [24]. Swissmedic declares “only information of a general nature about health or diseases” [25] as permissible. It is important that the information does not refer directly or indirectly to a specific drug. The active ingredient designation “botulinum toxin” can be used as the heading of a section or in the explanation of the term “Botox treatment” within a continuous text [25]. Under no circumstances, however, are special advertising campaigns for treatments with botulinum toxin permitted, which affect the price of the treatments [26].

Which drugs are covered by the health insurance?

Which drugs are covered by basic insurance is explicitly regulated by law. The Federal Office of Public Health compiles the list of specialties, in which the products including their costs are listed that are covered by the basic insurance as a maximum. It is an exhaustive list, i.e. if a product is not on the list, the basic insurance will refuse to cover the costs. However, the assumption of costs by a concluded supplementary insurance is not excluded. Cost coverage depends on the respective supplementary insurance.

The current specialty list can be found online at www.spezialitätenliste.ch. The search function includes preparation names, marketing authorization holders or active ingredients.

Which treatments are covered by health insurance?

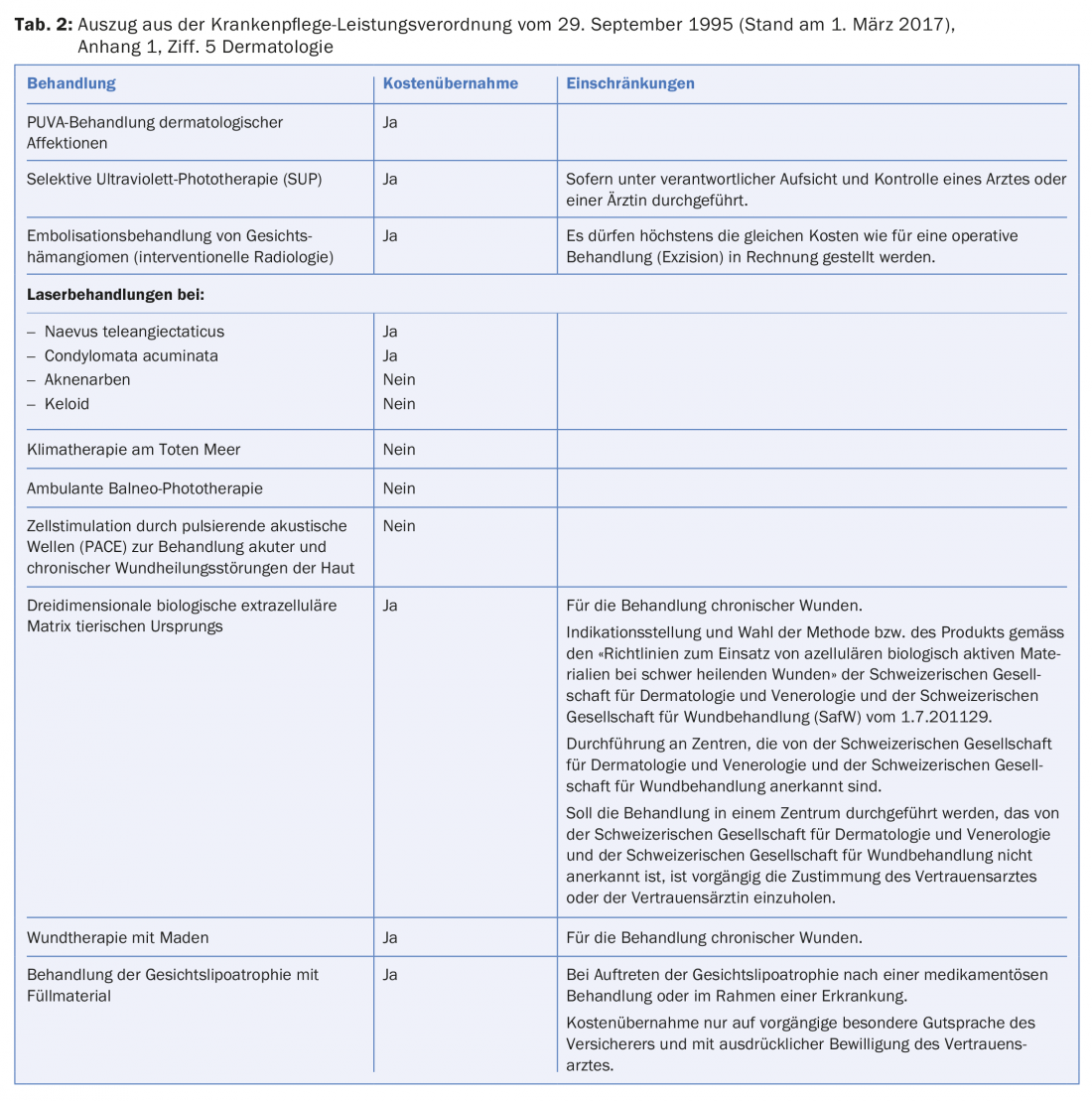

There is no exhaustive list for medical services. However, the health insurance fund must generally cover a dermatological service because it is presumed to meet the criteria of effectiveness, expediency and economic efficiency. These criteria are required for cost coverage by the basic insurance [27]. The health insurance company may refuse to pay the benefit by showing that these criteria are not met. However, Appendix 1 of the Health Care Benefits Ordinance contains a list of treatments, which is a non-exhaustive binding list of mandatory or non-medical services. For example, PUVA treatment of dermatological affections is covered by health insurance and outpatient balneo-phototherapy is not (Tab. 2) [28].

Take-Home Messages

- The duty to maintain medical devices is incumbent on the person who uses them on third parties.

- Violations of the maintenance obligation are sanctioned as misdemeanors by Swissmedic.

- Practices that perform Class 3B or Class 4 laser treatments must designate a laser safety officer.

- Physician advertising must be objective, meet a public need, and not be misleading or intrusive. Information that primarily serves an end in itself is inadmissible.

- Caution should be exercised in providing information and advertising botulinum toxin treatment.

- The Health Care Benefits Ordinance contains clear regulation on the reimbursement of selected dermatological treatments.

Sources:

- Art. 49 par. 1 HMG; Art. 20 MepV; Information sheet of the Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products, Medical Devices: Maintenance, Reprocessing, Modification by Specialists, as of June 2005, p. 1.

- Cf. for the whole information sheet of the Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products, Medical Devices: Maintenance, Reprocessing, Modification by Specialists, June 2005, p. 2 ff.

- Cf. art. 86 par. 1 lit. f HMG.

- EKAS Guideline No. 6508, ASA Guideline of December 14, 2006 (as of January 1, 217), para. 2 in conjunction with. Appendix 1; SUVA, Achtung, Laserstrahl!, p. 12; cf. also laser safety standard EN 60825-1.

- Cf. SUVA, Attention, laser beam!, p. 12.

- Cf. 101 II 84 f. E. 3; 107 II 175 E. a.

- Cf. e.g. judgment of the BGer 4C.82/2004; judgment of the BGer 4D_25/2010.

- Cf. on the whole Art. 197 ff.

- Art. 40 lit. d MedBG.

- Art. 43 par. 1 MedBG.

- Message on the Federal Law on the Medical Professions at Universities (MedBG) of December 3, 2004, p. 228.

- Art. 43 StaO FMH.

- Art. 20 par. 1 StaO FMH.

- Art. 20 par. 2 StaO FMH.

- Art. 20 par. 3 StaO FMH.

- Digit. 1.1. Appendix 2 to the FMH Code of Professional Conduct (“StaO FMH”) contains the guidelines “Information and Advertising”.

- Digit. 2.3. Annex 2 to the StaO FMH.

- Digit. 3.2. Annex 2 to the StaO FMH.

- Keller Claudia, Chapter 4: Advertising Law, in: Social Media und Recht für Unternehmen, para. 4.26.

- Art. 32 par. 2 lit. a HMG.

- Ruling of the BVerwG C-546/2010; BGE 129 V 32.

- Ruling of the BVerwG C-546/2010; ruling of the BGer 2A.63/2006.

- Art. 87 par. 1 lit. b HMG.

- Cf. judgment of the BVerwG C-546/2010.

- Swissmedic, AW Fact Sheet, Botulinum toxin – Guidelines, Botox: information versus advertising, p. 1.

- Cf. Swissmedic, AW Fact Sheet, Botulinum toxin – Guidelines, Botox: information versus advertising, p. 3.

- BGE 129 V 167, E. 3.2; BGE 125 V 28 E. 5b.

- Cf. para. 5 Dermatology, Annex 1 of the KLV.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2017; 27(3): 25-28