The eighth spring cycle took place at Lucerne Cantonal Hospital in March. Among the topics discussed were the cardiovascular effects of regular physical activity. How important is physical activity for cardiac prevention and what is the risk of sudden cardiac death? Are patients with heart problems also allowed to exercise? Furthermore, the focus was on hormonal diseases. Hypothyroidism, a common endocrinologic condition, is particularly challenging in the subclinical setting.

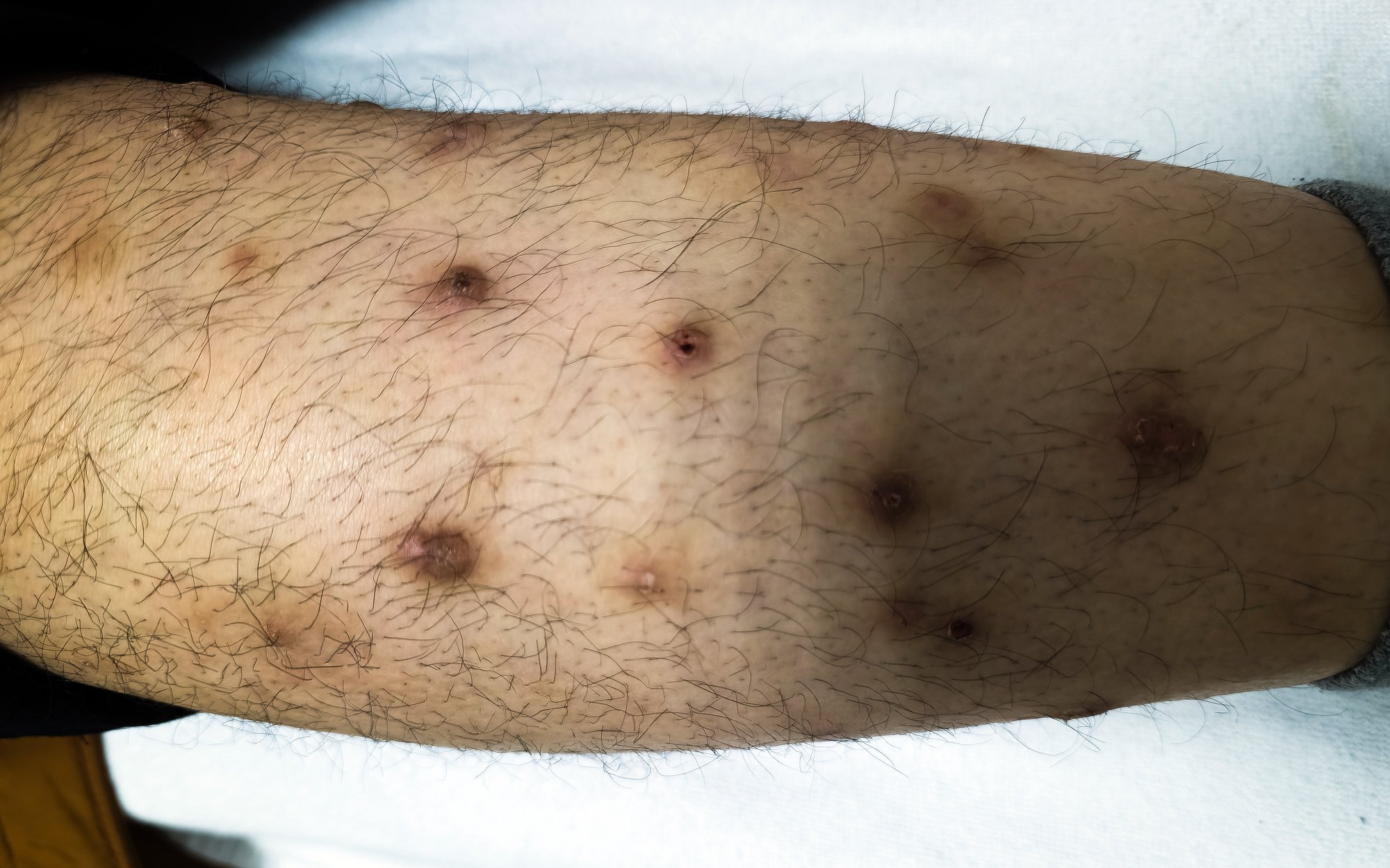

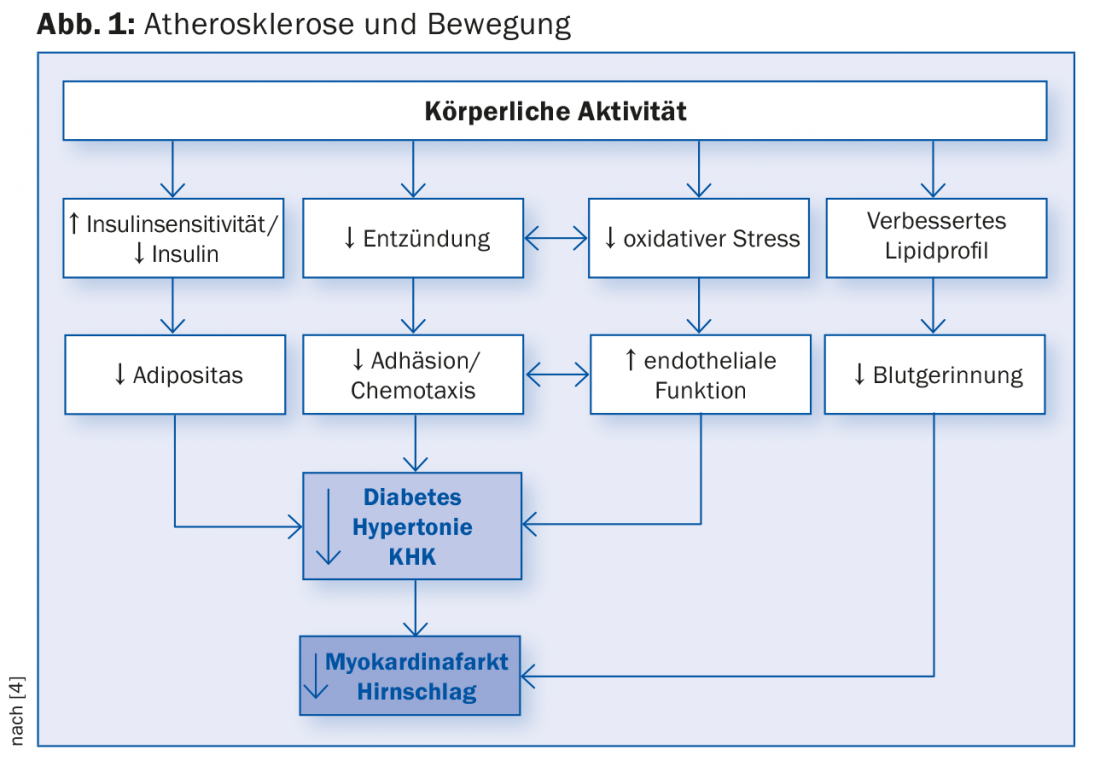

In Switzerland, people have been doing more sports, especially since the mid-1990s: The number of people who are active in sports several times a week is increasing significantly, which puts our country in second place in a European comparison (right behind Sweden). According to Urs Jeker, M.D., chief physician of cardiology at the Lucerne Cantonal Hospital, the preventive effect of exercise is also increasingly recognized by the population, and even the over-65s are staying physically active. “Prevention of cardiovascular disease is partly responsible for the huge increase in life expectancy over the past 20 years,” Dr. Jeker said. “The development of atherosclerosis, for example, can go back to childhood and thus can also be positively influenced at that time” (Fig. 1).

The consistent and comprehensive treatment of coronary artery disease (CAD) is based on three pillars: revascularization, drug therapy and lifestyle adaptation. Several studies have shown that cardiac rehabilitation has a positive impact on coronary sclerosis. It reduces all-cause and cardiac mortality [1] and subsequent coronary events and hospitalizations. Higher exercise capacity or resilience in patients with CHD results in a significant survival benefit of 45% [2].

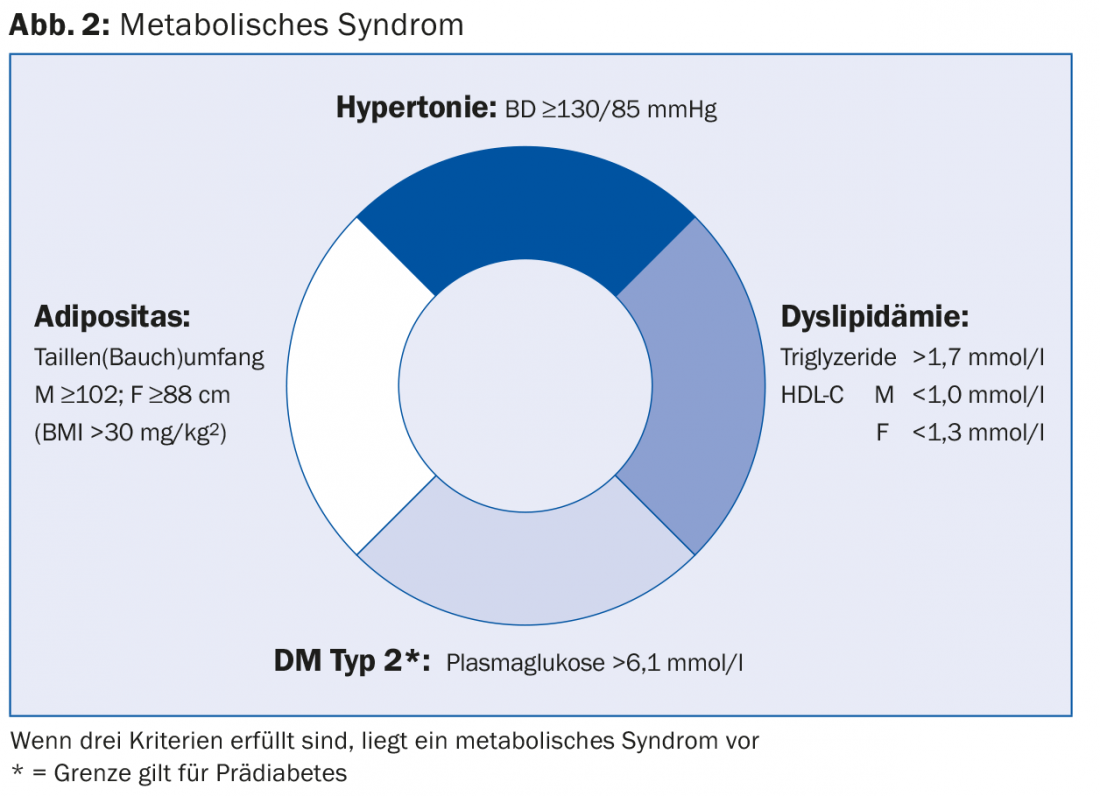

“Instead of just talking about sports and exercise, we should therefore use the term fitness,” Dr. Jeker recommended. Fitness describes the physical and mental well-being as well as the performance and resilience in everyday life. The risk of “civilization diseases” (coronary, peripheral arterial, cerebrovascular) decreases. “Cardiorespiratory fitness is critical for primary prevention and the best anti-aging tool we have. It prolongs our lives and makes cardiovascular events less likely [3],” the speaker said. Such a lifestyle does not succeed by chance: “Basically, we live in an unhealthy age: In our professional and private everyday life, movement hardly plays a role anymore. The deadly quartet of a metabolic syndrome (Fig. 2) must be actively prevented.” For example, a study by Tuomilehto and colleagues [5] showed that exercise training and weight loss increased the probability of not developing type 2 diabetes mellitus by 20% in 522 overweight people with impaired glucose tolerance (high-risk population).

Cardiac prevention

The motto regarding heart-friendly sports is: “It matters less what you do, as long as you do it.” At low baseline activity, the training effect or health gain is the greatest. A training session is therefore already much more effective than no training session, which is crucial information, according to Dr. Jeker. It is quite common for people to be put off by exercise recommendations and to be under the misapprehension that if they don’t do the recommended 30 minutes of exercise a day, they might as well not do it.

For cardiac patients, however, watch for the following warning signs as part of controlled exercise training:

Angina pectoris (new or increased)

- Rhythm disturbances under stress

- Dizziness under load

- Infection (additional circulatory load)

- Heart failure or severely impaired pump function

- accompanying vegetative symptoms (pallor, cold sweatiness)

- incomplete revascularization.

“Threatening situations arise from malignant arrhythmias, ischemia, or excessive sympathicotonia,” the speaker said. The sports fitness of cardiac patients can be assessed in the field of recreational sports by history, clinic, and exercise testing. Competitive sports, on the other hand, may only take place under defined conditions after echo and ergometry. Apart from a few exceptions (which have been clarified by a specialist), top-level sports should be avoided.

Risk stratification

And what about the relationship between exercise and cardiac risk? One feared consequence of physical activity is sudden cardiac death, which can occur even in (supposedly) healthy individuals. According to PD Dr. med. Richard Kobza, head of cardiology at Lucerne Cantonal Hospital, this is by definition a natural death that occurs within one hour of the onset of symptoms. The professional footballers Marc-Vivien Foe and Miklós Fehér, who collapsed and died during a match in 2003 and 2004 respectively, became sadly famous in this respect. In fact, the relative risk of such death is increased 2.8-fold in athletes compared with non-athletes [6]. But what is often forgotten: Intensive exercise is not itself a causal cause of cardiac mortality, but a trigger for previously undiagnosed underlying cardiac diseases. In 95% of cases, sudden cardiac death is due to structural heart disease. In about 15%, the first symptom of heart disease is sudden cardiac arrest. Athletes have an increased risk, especially at a young age (which also has to do with the career that usually takes place during this period), while the rate in the general population increases significantly from around 40 years of age. In professional athletes under 35 years of age, cardiomyopathies, coronary anomalies, myocarditis, WPW syndrome, and ion channel disease are primarily responsible for sudden cardiac death – in those over 35, it is atherosclerotic coronary artery disease. This also accounts for by far the largest proportion of underlying cardiovascular abnormalities in the general population [7].

Screening consisting of medical history, physical examination and ECG can reduce the rate of sudden cardiac deaths in athletes: In Italy, where such screening has been mandatory since 1982, a reduction of 89% in sudden deaths has been achieved in athletes.

“Also dangerous is only sporadic and then very intense sporting activity. The risk of infarction as a result of Effort stress is three to five times higher in people over 40,” warned Dr. Jeker. “Such over-exercise carries more risks than benefits. Profit comes only from restorative regular physical activity.”

Hormone diseases in practice – Hypothyroidism

About 0.1-2% of the population have manifest hypothyroidism, thyrotropin (thyroid-stimulating hormone, TSH) is elevated and free thyroxine (fT4) is decreased. However, a good 4-10% have a subclinical form in which fT4 is in the normal range and only TSH is elevated (in 80% <10 mU/l). “Here, the symptoms, if there are any at all, are mostly non-specific and not related to thyroid function [8]. It is also unclear whether such patients should already be treated,” says Stefan Fischli, MD, Head Physician of Endocrinology and Diabetology at Lucerne Cantonal Hospital. One thing is certain: With a TSH value below 10 mU/I there is no general indication for therapy. Rather, an individualized approach is recommended.

Primary hypothyroidism is almost always caused by Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (other causes are much rarer). Central/secondary hypothyroidism, in turn, occurs about a thousand times less frequently than the primary form. Risk factors for hypothyroidism include goiter, autoimmune diseases (personal/family history) such as type 1 diabetes, Down/Turner syndrome, radiation therapy/surgery, time after childbirth, medications such as amiodarone, lithium, or tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

If primary hypothyroidism is suspected, the first diagnostic step should be a TSH determination. If the value is normal, there is no such disease – if it is elevated, the fT4 determination shows whether it is a subclinical (normal fT4 value) or manifest hypothyroidism (lowered fT4 value). Possibly, a sonography of the thyroid gland can be performed in addition – according to Dr. Fischli, however, not routinely (reasonable indications are clinically determined goiter/node and an antibody-negative hypothyroidism).

Ultrasound examination is also an option in the subclinical form ; in addition, anti-TPO antibodies can confirm the (differential) diagnosis here. Huber and colleagues [9] have shown that both measurement of TSH and detection of antibodies have prognostic relevance: After ten years, 0% (TSH 4-6 mU/l), 42.8% (TSH >6-12 mU/l) and 76.9% (TSH >12 mU/l) of the 82 women studied developed manifest hypothyroidism (p<0.0001). Patients with positive antibodies had an incidence rate of 58.5% – compared to 23.2% with negative antibody detection (p=0.03).

“If secondary or central hypothyroidism is suspected, one should always determine TSH and fT4 levels,” the expert explained. “Otherwise, the diagnosis will be missed.”

Differential diagnosis and treatment

The presence of concomitant diseases and the use of medications are critical factors in the interpretation of thyroid function. During the convalescence phase after severe illness, there is almost always a passive increase in TSH (non-thyroidal illness syndrome, NTIS), so thyroid function should not be assessed until after the illness has healed.

The standard of care is levothyroxine monotherapy. The starting dose should be chosen individually and sometimes depends on the etiology and severity of the hypofunction (it is usually about 1.6 µg/kg bw per day). Potential interactions with other medications or even foods must be considered: Calcium, iron salts, multivitamin preparations, oral bisphosphonates, phosphate and bile acid binders reduce levothyroxine absorption – as do coffee and breakfast cereals, as Benvenga and colleagues showed in 2008 [10]. Taking it on an empty stomach at least 30 minutes before breakfast is therefore mandatory.

In subclinical hypothyroidism, levothyroxine administration reliably prevents progression to the manifest form – however, with regard to other parameters (symptoms, cardiac health), the benefit is not well established scientifically and there is little evidence [8]. “If TSH elevation is >10 mU/l, treatment is recommended in any case. For values below that, which is much more common, individual risk stratification has to be done,” Dr. Fischli explained. Hormone replacement therapy is useful in the following cases (patients <70 years):

- Highly positive anti-TPO antibodies

- Pregnancy/childbearing

- Struma

- Symptoms/dyslipidemia

- CV risk profile/disease.

If no such parameters are available, follow-up after 6-12 months is recommended. Slightly elevated values often return to the normal range in a follow-up check.

Source: 8th Spring Cycle, March 11-13, 2015, Lucerne

Literature:

- Taylor RS, et al: Am J Med 2004 May 15; 116(10): 682-692.

- Myers J, et al: N Engl J Med 2002 Mar 14; 346(11): 793-801.

- Kodama S, et al: JAMA 2009 May 20; 301(19): 2024-2035.

- Roberts CK, Barnard RJ: J Appl Physiol (1985). 2005 Jan; 98(1): 3-30.

- Tuomilehto J, et al: N Engl J Med 2001 May 3; 344(18): 1343-1350.

- Corrado D, et al: J Am Coll Cardiol 2003 Dec 3; 42(11): 1959-1963.

- Marijon E, et al: Circulation 2011 Aug 9; 124(6): 672-681.

- Surks MI, et al: JAMA 2004 Jan 14; 291(2): 228-238.

- Huber G, et al: J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002 Jul; 87(7): 3221-3226.

- Benvenga S, et al: Thyroid 2008 Mar; 18(3): 293-301.

GP PRACTICE 2015; 10(4): 36-39