Atrial fibrillation is the most common cardiac arrhythmia and is associated with an increased risk of embolic events. Routine screening facilitates timely detection and treatment. Oral anticoagulants are recommended as therapy in most cases, and the risk of bleeding and stroke can be assessed by specific scores. The NOAK/DOAK substance class is nowadays considered more important than vitamin K antagonists.

It is estimated that at least a quarter of current 40-year-olds will develop atrial fibrillation during their lifetime. This is associated with an increased risk of stroke and mortality. Nowadays, a broad arsenal of active substances is available for drug treatment. “The indication for oral anticoagulation must always be reviewed,” emphasizes Prof. Christian Sticherling, MD, dept. Chief Physician at the University Hospital Basel [1]. The HAS-BLED score can be used to estimate the risk of bleeding [2]. The diagnostic finding in atrial fibrillation is an ECG with irregular RR intervals without clearly delineated P waves. Long-term ECG monitoring improves the probability of detection. Many affected individuals have both symptomatic and asymptomatic episodes of atrial fibrillation. In patients >65 years of age, current ESC guidelines recommend screening by occasional pulse measurement or ECG recording [3]. In patients who have suffered a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or an ischemic stroke, ECG including long-term measurement should be performed. Regular screening for asymptomatic high-frequency episodes (AHRE) is indicated in pacemaker patients. If AHRE is detected, further ECG monitoring and stroke risk assessment should be performed before initiating therapy. Systematic ECG screening to detect atrial fibrillation may be considered in patients over 75 years of age or in patients in other age groups at high risk for stroke.

Increased risk of cerebrovascular events

Approximately 30% of all strokes are associated with atrial fibrillation and hospitalization rates of atrial fibrillation patients in general are 10-40% annually [3]. In particular, ESUS (Embolic Stroke of undetermined source), which account for about 25% of all ischemic stroke events, often occur due to atrial fibrillation, the speaker explained [1,4]. The Swiss-AF Cohort Study (Swiss Atrial Fibrillation Cohort Study) investigates the long-term course of cognitive functions in atrial fibrillation in relation to structural changes in the brain. Partial results published in JACC show that clinical and subclinical brain lesions are common in patients with AF and may be associated with decreased cognitive performance [5]. In patients who had suffered an idiopathic stroke, continuous monitoring with the implantable Reveal cardiac monitor is superior to standard monitoring for the detection of AF, as the results of the CRYSTAL-AF trial make clear [6].

One of the aims of the Apple Heart Study was to detect silent AF in patients with elevated CHA2DS2 VASc score [7]. The large-scale study using the Apple Watch is based on the knowledge that atrial fibrillation is often asymptomatic and is only noticed with the occurrence of embolic events. Based on pulse measurement with the aid of optical sensors, it is possible to draw conclusions about atrial fibrillation in the case of irregular pulse waves by means of algorithms. In 2161 of 419,297 healthy volunteers, the Apple Watch registered an irregular pulse. Atrial fibrillation or flutter was detected in slightly more than one-third of the 450 patients who subsequently underwent measurement with the ECG patch. The proportion of subjects in whom an irregular pulse was detected was therefore relatively low and the compliance of the study participants concerned with regard to a subsequent ECG patch measurement was not very high. From a technological point of view, however, it is an interesting approach and it is an uncomplicated measurement method that is compatible with everyday life. It is expected that similar studies will be conducted in the future to evaluate the clinical benefits and privacy risks of using these digital devices.

NOAKs are favored over vitamin K antagonists

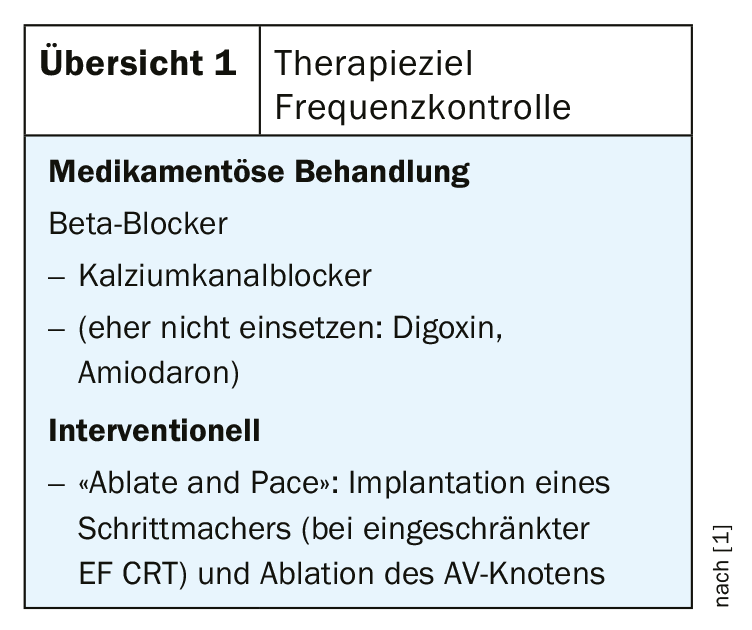

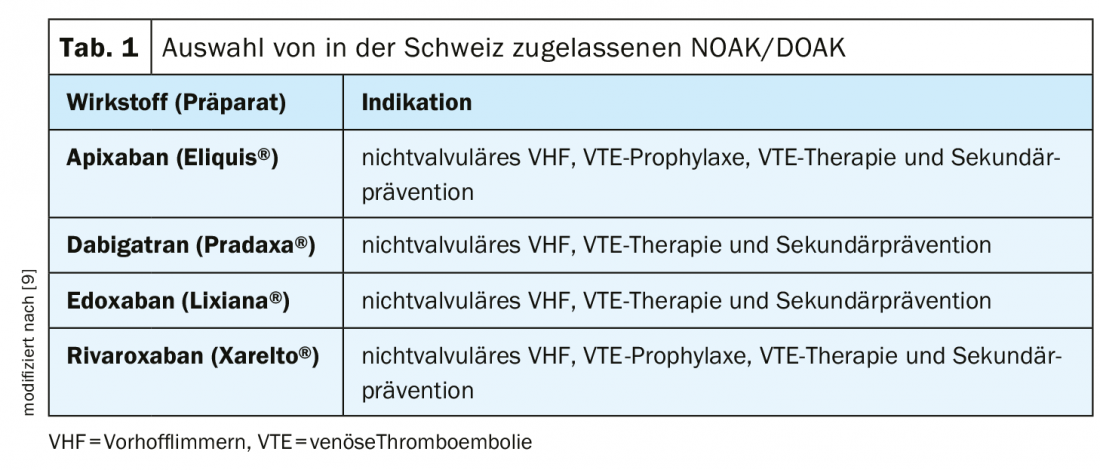

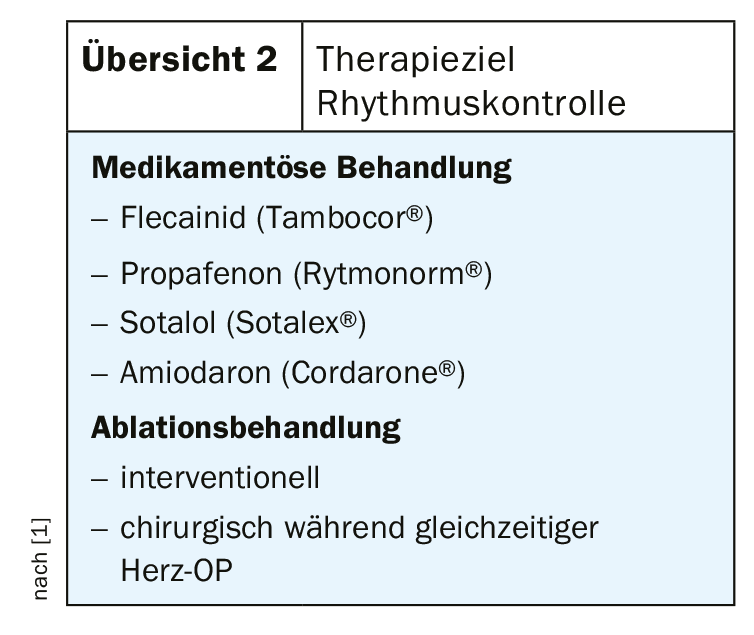

According to current knowledge, oral anticoagulation should be recommended for most atrial fibrillation patients [3]. For a differentiated risk stratification of stroke and bleeding risk, the following scores exist [2]: HAS-BLED score (bleeding risk), CHA2DS2-VASc score (stroke risk) [3]. With a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1 (men) resp. 2 (women), anticoagulation should be considered after weighing the individual bleeding risk [8]. A HAS-BLED score of ≥3 is considered an increased risk of bleeding, although this does not necessarily mean discontinuation of oral anticoagulation, but it is recommended to identify treatable bleeding risk factors [8]. There are many factors to consider when choosing an anticoagulant. In the current ESC guidelines [3], NOAKs (new oral anticoagulants), also called DOAKs (direct oral anticoagulants), have a stronger recommendation than vitamin K antagonists. A selection of NOAK/DOAK representatives approved in Switzerland is shown in Table 1. Except in patients with valvular atrial fibrillation or artificial heart valve, in whom vitamin K antagonists are still indicated, NOAK/DOAK are favored today. Meta-analyses indicate that NOAKs/DOAKs confer significantly better protection against cardioembolic events compared with vitamin K antagonists, mainly due to a lower rate of intracranial hemorrhage [8]. In addition, NOAK/DOAK offer the advantage that a fixed dosage can be selected and the need for regular coagulation monitoring is eliminated. In addition to established drugs (beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers), pacemaker implantation and AV node ablation are also available for the therapeutic goal of frequency control, especially in older patients (overview 1) . If the treatment goal is rhythm control, class Ic antiarrhythmics should be used primarily, according to Prof. Sticherling (overview 2) [1]. Lifestyle may also have an impact, on incidence and disease progression. Modifiable lifestyle factors that reduce the risk of atrial fibrillation recurrence include weight reduction, physical activity, and alcohol abstinence. This has been empirically demonstrated, such as in the Cardio-Fit study (n=308) [10] or the Alcohol-AF study (n=140) published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2020.

Source: FOMF Basel 2020

Literature:

- Sticherling Ch: Atrial fibrillation: Diagnosis and therapy. Prof. Christian Sticherling, MD, FOMF Basel, Jan. 31, 2020.

- Pisters R, et al: A Novel User-Friendly Score (HAS-BLED) To Assess 1-Year Risk of Major Bleeding in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Chest 2010; 138(5): 1093-1100.

- Kirchhof P, et al: 2016 ESC Guidelines on atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 2893.

- Gladstone. Atrial Fibrillation in Patients With Cryptogenic Stroke. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 2467.

- Conen D, et al: Relationships of Overt and Silent Brain Lesions with Cognitive Function in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. JACC 2019; 73(9): 989-999. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc. 2018.12.039.

- Sanna T, et al: Cryptogenic stroke and underlying atrial fibrillation (CRYSTAL AF). N Engl J Med 2014; 370(26): 2478-2486.

- Perez MV, et al: Large-Scale Assessment of a Smartwatch to Identify Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 1909-1917.

- Altiok E, Marx N: Oral anticoagulation. Update on anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists and non-vitamin K-dependent oral anticoagulants. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2018; 115: 776-783.

- Rosemann A: New/Direct Oral Anticoagulants, 7/2018, www.medix.ch

- Pathak RK, et al: Impact of CARDIOrespiratory FITness on Arrhythmia Recurrence in Obese Individuals With Atrial Fibrillation: The CARDIO-FIT Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 66(9): 985-996.

- Voskoboinik A, et al: Alcohol Abstinence in Drinkers with Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 20-28.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2020; 15(9): 37-38 (published 9/17/20, ahead of print).