Calcium plays a central role in bone health and in the prevention of osteoporosis. Vitamin D promotes the absorption of calcium in the metabolism. Especially for older people, an adequate supply of vitamin D and calcium is important, as it can reduce the risk of fractures. What needs to be considered to ensure this?

Vitamin D has a special role in human nutrition: it can be formed endogenously via the skin if there is sufficient exposure to sunlight, and it can also be supplied exogenously via food and supplements. Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin found in plant foods as vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) and in animal foods as vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol). Together with dietary fats, these calciferols are transported from the intestine in the chylomicrons via the lymph to the liver.

In human skin, vitamin D3 can be formed by UVB radiation of wavelength 290-315 nm. However, endogenous vitamin D3 formation is insufficient in Switzerland during the winter months, so that about 60% of the Swiss are undersupplied during this period. The missing amount must then be supplied through food.

Vitamin D, together with calcium, plays a crucial role in calcium and phosphate metabolism. Vitamin D is also involved in the prevention of various chronic diseases, as its active form participates in over 6000 gene expressions. In older age, both the absorption of vitamin D via the intestine and the formation in the skin decrease. This results in more frequent cases of osteoporosis.

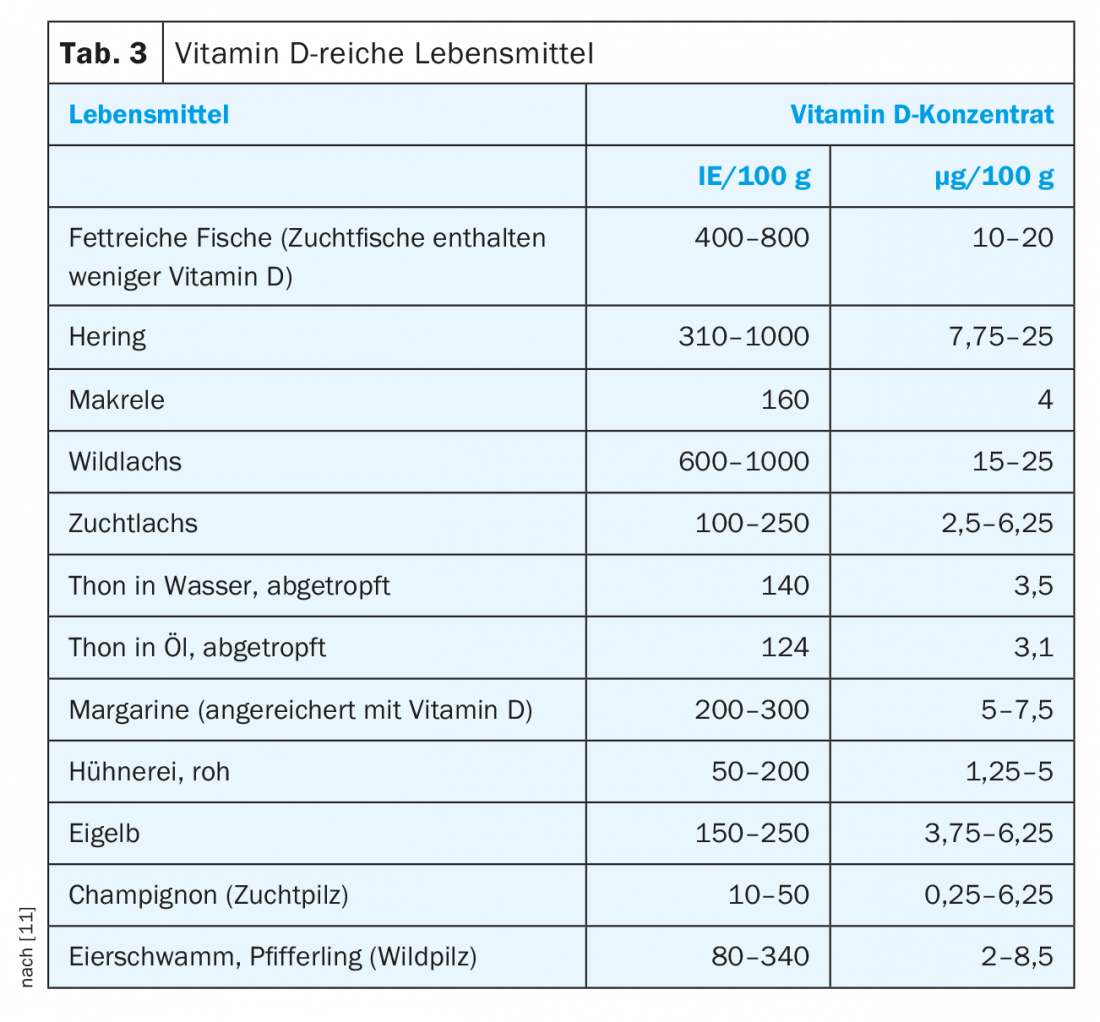

Foods contain relatively little vitamin D. Foods rich in vitamin D, on the other hand, are fatty fish, fatty hard cheeses, some mushrooms and egg yolks. According to the D-A-CH reference values, older people (≥65 years) should take 20 μg (800 IU) of vitamin D daily. The reduced synthesis capacity of the skin in older age is taken into account. A level of 50 nmol/l of the active form of vitamin D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, in blood plasma is considered the cutoff for insufficiency [11]. However, different methods may produce different results. To minimize the risk of falls, individuals 60 years of age and older should have 25(OH)D concentrations of ≥75 nmol/l.

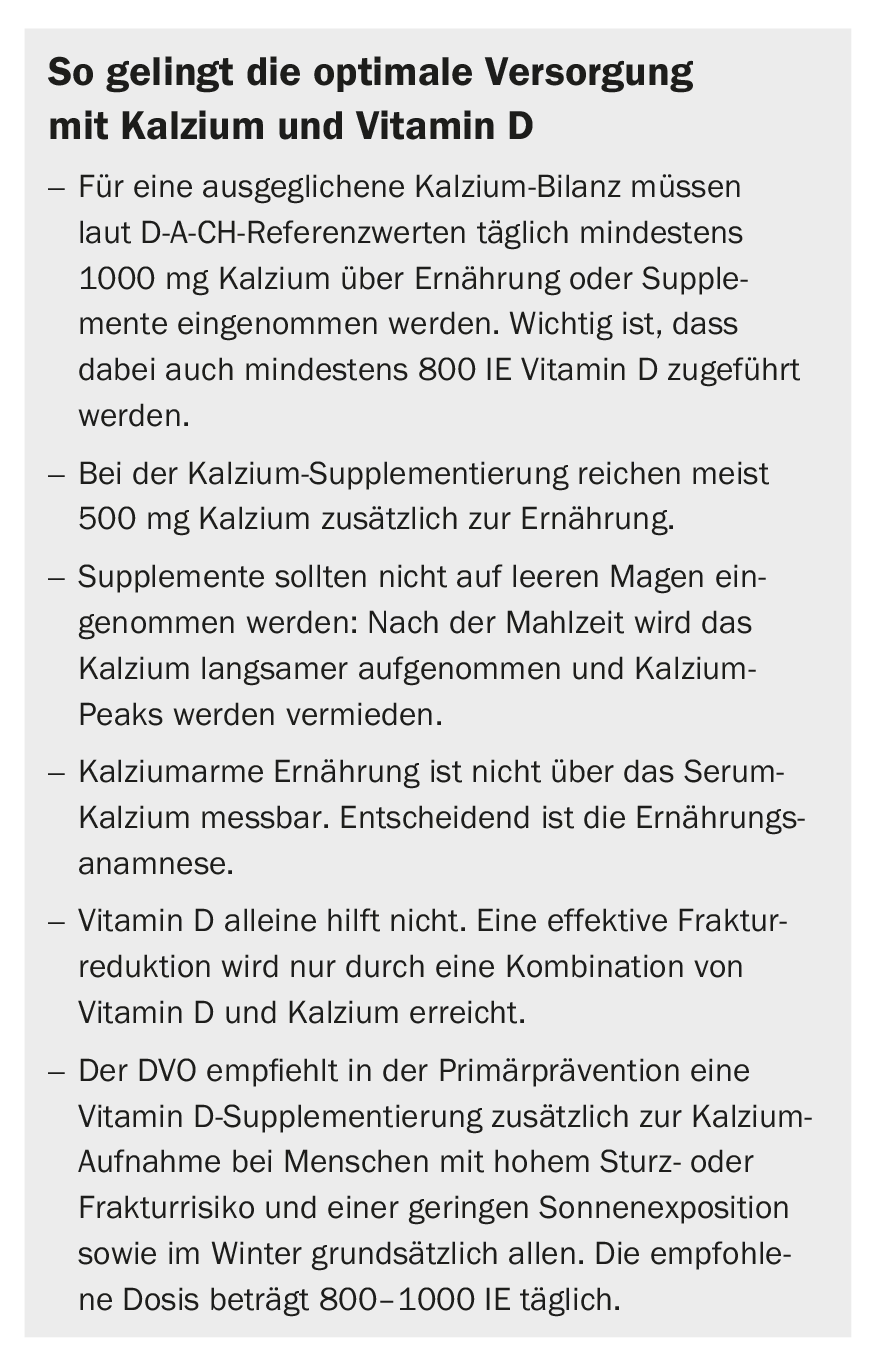

Calcium plays a crucial role in bone health in particular. Almost 100% of the body’s calcium supply is incorporated in the bones and teeth. The calcium requirement of 1000 mg/day in people ≥65 years of age can be met with an average diet. However, calcium can only be absorbed with the help of vitamin D and incorporated into the bones. Therefore, supplements in the form of a combination of calcium and vitamin D are useful. The currently ongoing DO-HEALTH study, one of the largest European aging studies, which is being conducted at the University Hospital Zurich, is currently investigating how we can grow older healthily and actively [2,3]. This study, led by Prof. Heike Bischoff-Ferrari, investigates three strategies: the effect of vitamin D3, the effect of omega-3 fatty acids (seaweed), and a home exercise program. Final results are expected in mid-2019.

Risks of disease in older age

From birth to adulthood, the human organism stores 30 to 35 times as much calcium in the skeleton, the largest reservoir of calcium. However, vitamin D is essential for bone formation [4]. At the age of about 30, humans reach maximum bone density, after which bone mass and density decrease. Bone resorption is slow, steady and painless. The greater the calcium stock (high bone density) laid down at a young age, the later osteoporosis occurs. The degradation process of the bone cannot be stopped, but it can be delayed [5]. Here, exercise, spending time in the air (sun) and sufficient supply of vitamin D, calcium, phosphorus and proteins via the diet are crucial [6].

Myopathy is considered a classic symptom of high-grade vitamin D deficiency in older age. Muscle pain, muscle weakness, and gait disturbances are the consequences that are reversible with vitamin D supplementation [4].

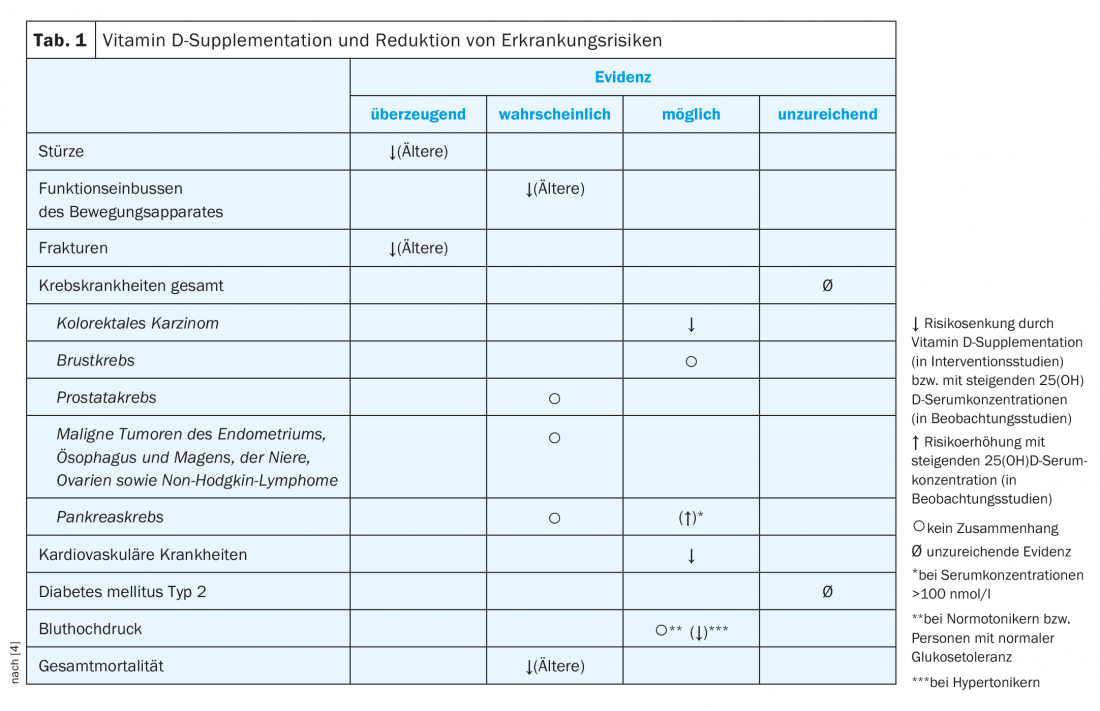

In old age, muscle mass and bone density decrease, and at the same time the risk of falls increases; around 90% of all fractures occurring in old age are caused by falls. Several meta-analyses and controlled trials have demonstrated associations between fall risk reduction and vitamin D and calcium supplementation [7,8], as well as positive influences on the functional musculoskeletal system [4]. However, possible links between increased risk of cancer, diabetes or hypertension and vitamin D supply are currently unclear. In contrast, an association between cardiovascular events and vitamin D supply is considered likely [4]. Several studies suggest that there is a correlation between a reduction in all-cause mortality and vitamin D supplementation [4] (Table 1).

Vitamin D and calcium: how and how much?

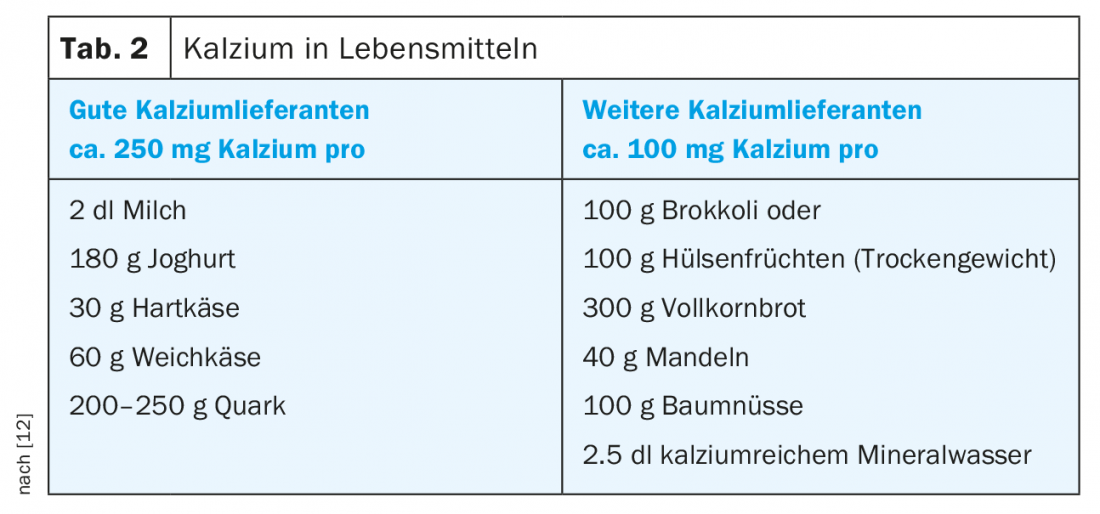

Calcium is the most important mineral in the body in terms of quantity. Almost 100% are stored in bones and teeth. The current recommended intake of calcium is 1000 mg/day. However, calcium can be absorbed from the intestine only with the help of vitamin D. The recommended amount can be well achieved through a balanced diet [9]. Milk and dairy products, broccoli, kale and arugula in particular, as well as mineral water, are important sources of calcium [10–12] (Tab. 2).

The guidelines of the umbrella organization Osteology recommend daily intake of 1000 mg calcium for postmenopausal women and men over 60 years of age for general osteoporosis and fracture prophylaxis, and an additional 800-1000 IU vitamin D/day for persons at high risk of falls and fractures and with low sun exposure [13]. The D-A-CH reference values for nutrient intake provide similar recommendations [1].

For calcium to be optimally stored in the bones, exercise, preferably outdoors with exposure to sunlight, is essential. Exercise should require muscle strength to create a stimulus to build bone mass. The WHO recommends walking at least 10,000 steps a day, which is equivalent to one hour of daily physical activity. Risk factors such as being underweight, smoking or excessive alcohol consumption should be avoided.

What to look for in terms of nutrition ?

There are foods that should be reduced in intake because they can affect the body’s phosphate-calcium balance and thus negatively impact bone health. Foods and stimulants whose consumption levels should be reduced if osteoporosis is present include:

- Phosphates from sweet drinks

- Salt (mainly in meat and sausage products and ready meals)

- Alcohol

- Coffee (maximum 3-4 cups/day)

- Tobacco

An overview of beneficial foods is provided in table 3. The tips in the box show what needs to be taken into account to ensure an adequate calcium and vitamin D supply.

Literature:

- German Society for Nutrition, Austrian Society for Nutrition, Swiss Society for Nutrition, eds: Reference Values for Nutrient Intakes, 2nd edition, 3rd updated edition. Bonn 2017.

- Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al: Monthly High-Dose Vitamin D Treatment for the Prevention of Functional Decline: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176(2): 175-183.

- Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al: Effect of high-dosage cholecalciferol and extended physiotherapy on complications after hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170(9): 813-120.

- German Society for Nutrition, ed.: Statement. Vitamin D and prevention of selected chronic diseases. 2011. www.dge.de/fileadmin/public/doc/ws/stellungnahme/DGE-Stellungnahme-VitD-111220.pdf, last accessed January 29, 2019.

- BAG: Vitamin D and solar radiation. March 10, 2017. Bern: Federal Office of Public Health 2017.

- Rizzoli R, et al: Nutrition and bone health in women after menopause. Womens Health 2014; 10(6): 599-608.

- Boonen S, et al: Need for Additional Calcium to Reduce the Risk of Hip Fracture with Vitamin D Supplementation: Evidence from a Comparative Metaanalysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92(4): 1415-1423.

- Tang BM, et al: Use of calcium or calcium in combination with vitamin D supplementation to prevent fractures and bone loss in people aged 50 years and older: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2007; 370(9588): 657-666.

- Knurick JR, et al: Comparison of correlates of bone mineral density in individuals adhering to lacto-ovo, vegan, or omnivore diets: a cross-sectional investigation. Nutrients 2015; 7(5): 3416-3426.

- Bohlmann F: Vitamin D. The deficiency vitamin in Switzerland. Tabula 2014; 3: 4-9.

- L’Allemand D, et al: Recommendations of the Federal Office of Public Health on vitamin D supply in Switzerland – what do they mean for the pediatrician? Paediatrica 2012; 23(4): 22-24.

- Swiss Society for Nutrition: Nutrition and Osteoporosis. 2011. www.sge-ssn.ch/media/merkblatt_ernaehrung_und_osteoporose_20111.pdf, last accessed 29 Jan. 2019.

- DVO, ed.: Prophylaxis, diagnosis and therapy of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and in men. Dachverband der Deutschprachigen Wissenschaftlichen Osteologischen Gesellschaften e.V. 2017 guideline. www.dv-osteologie.org/dvo_leitlinien/dvo-leitlinie-2017, last accessed January 29, 2019.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(2): 10-14