Demographic change also brings new challenges to medicine. Polymorbid patients require an individual and at the same time holistic approach. What treatment is appropriate in these cases and when should maximal therapy be considered?

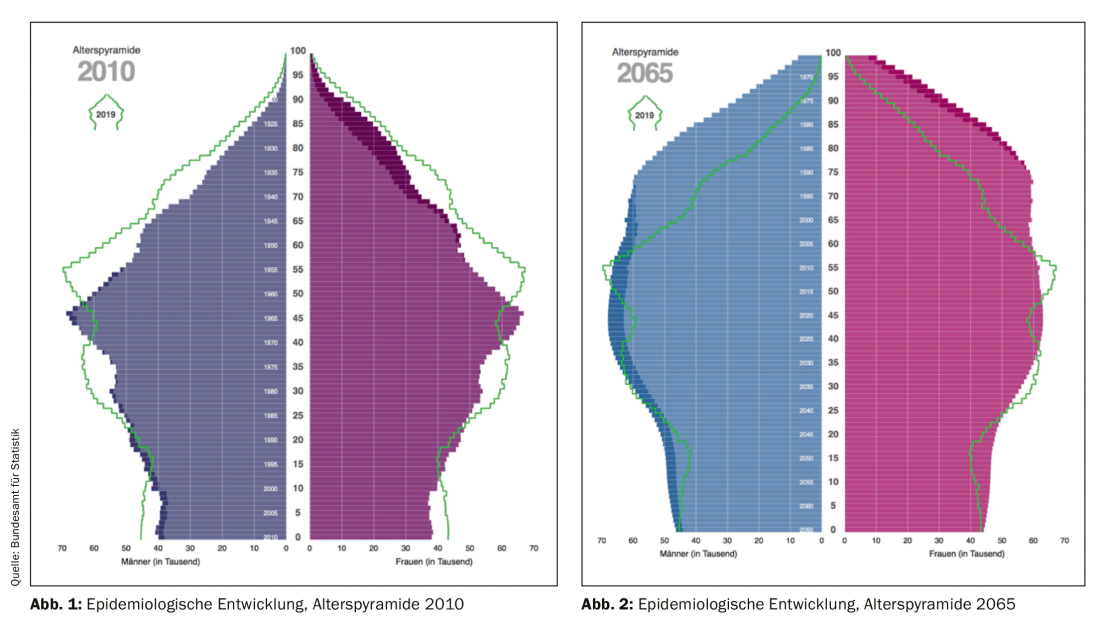

The patient population of the “elderly patient” requires a more precise definition and this represents the first hurdle of a structured treatment of the topic. In the literature one can find different definitions for age. Exemplarily, old age is described as the period of life between middle adulthood and death [2]. The demographic change in society represents a major challenge. In the last 10 years, Swiss society has been characterized by growth and an aging population. At the end of 2018, approximately 1.6 million people were at least 65 years old, representing just under 20% of the population (Fig. 1) [20]. Life expectancy in Switzerland continues to rise. Since 1990, mean life expectancy has increased by 7.5 years for men and 4.5 years for women. It is currently 83 years [19]. The Swiss Federal Statistical Office develops scenarios for Swiss population development. According to these scenarios, by 2065 the population share of people over 65 could be about 30% (Fig. 2) [6,11,19]. Medical advances are mainly responsible for these developments. Although the proportion of deaths from cardiovascular disease was reduced by 20% between 1995 and 2014 in Switzerland, one third of society continues to die from cardiovascular disease [11]. In the future, there will be more spry/healthy elderly patients on the one hand, but more sick/polymorbid patients on the other. An increasing demand for healthcare services may be assumed.

What is maximum therapy? Maximum therapy can include all technical and medical options. However, does this make sense? It seems to make more sense to aim for a maximum therapy individually related to the underlying disease, comorbidities and the will of the patient. A purely cardiologic focus is not appropriate in this context.

The needs and priorities of people older than 75 years differ from patient populations studied in most cardiology trials and guidelines (40-75 years). The wishes of the elderly are not the same as those of family members, caregivers, or the physicians providing care. Maintaining independence, everyday functions and living arrangements are central. For example, remaining in familiar surroundings and avoiding pain and worry is a priority.

This holistic view of needs, in the context of medical options and implications, is becoming increasingly important. Here, more importance is given to the assessment of biological age [12]. The chronological age increasingly diverges from the calendrical age. New investigations with more holistic assessments are gaining importance to objectify biological age and meaningful therapy. In this regard, in addition to geriatrics, there are also efforts in cardiology, especially to better assess biological age. The next section provides examples of some key cardiology areas related to the current guidelines with a focus on the elderly patient.

Arterial hypertension

Data from the 2012 Swiss Health Interview Survey powerfully illustrated the importance of arterial hypertension as we age. Among those aged 65 to 74 years, 47% of men and 38% of women receive antihypertensive treatment, and among those aged 75 years and older, more than half receive antihypertensive treatment [11]. In 2018, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) published new guidelines regarding the management of arterial hypertension. In patients over 65 years of age, a target systolic blood pressure of 130-139 mmHg now applies. These blood pressure targets apply regardless of comorbidities. However, the determination of blood pressure target values should take into account the tolerability of the therapy. It makes sense to follow the elderly patient more closely to detect potential adverse effects early (examples: Symptomatic hypotension, orthostatic complaints, deterioration of renal function, electrolyte disturbances) [8,9,13].

Coronary heart disease

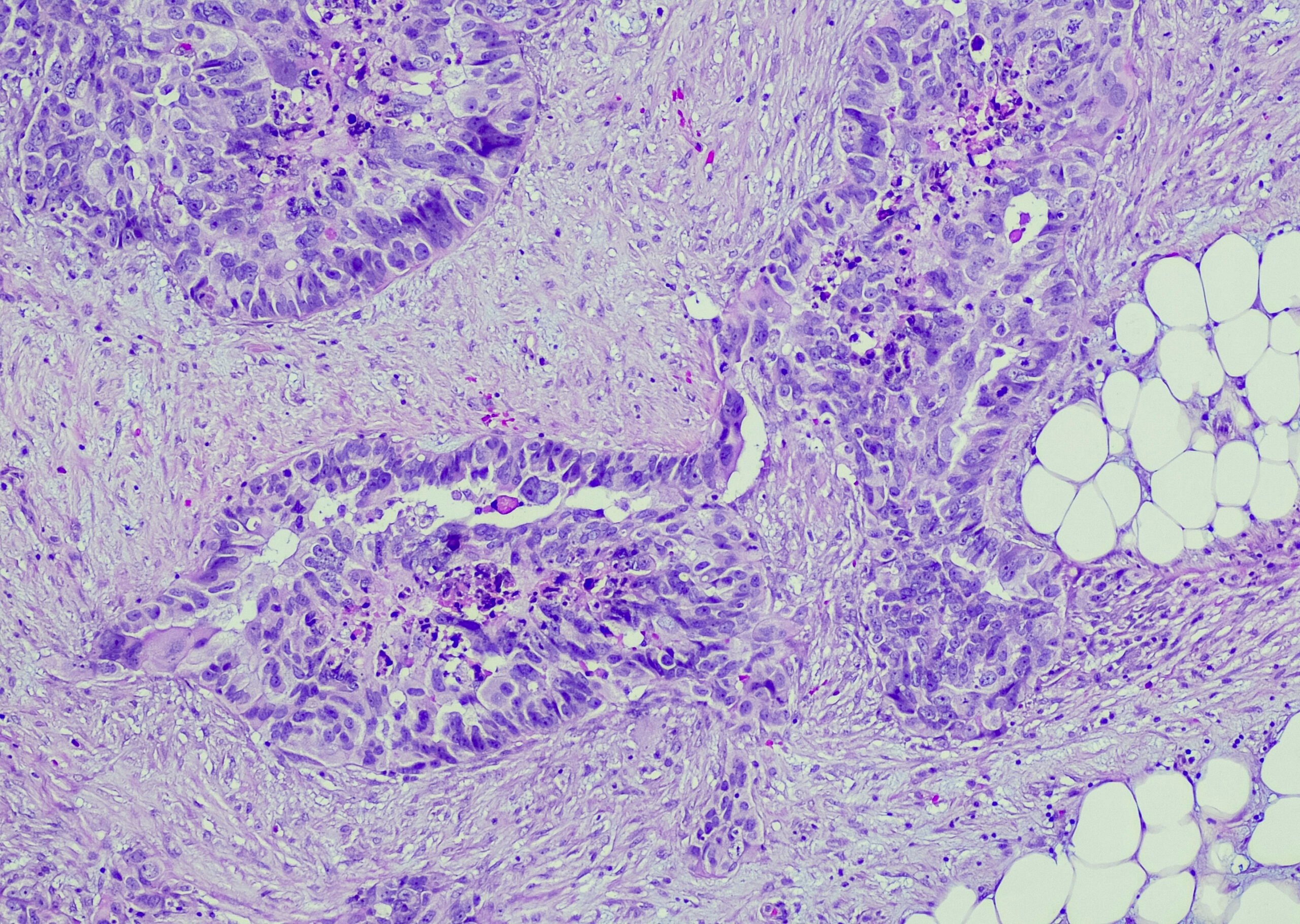

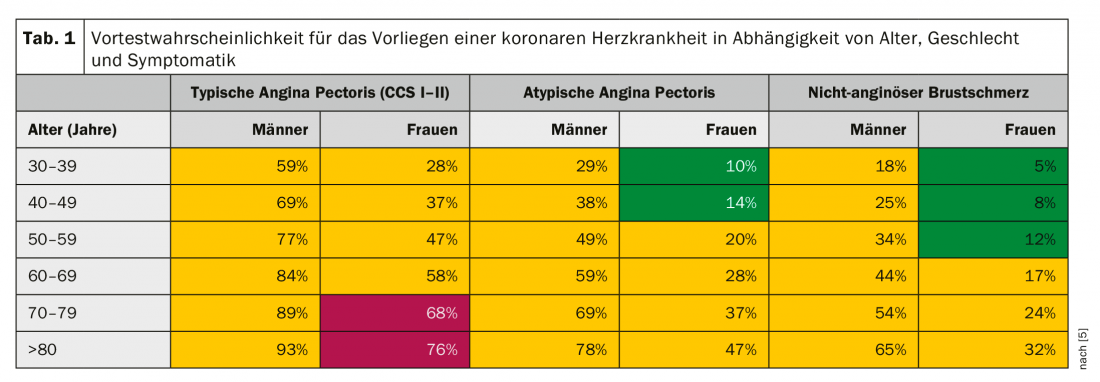

Age has a critical impact on coronary artery disease (CAD), related to clinical presentation, pretest probability of relevant coronary stenosis, and diagnostic as well as therapeutic recommendations. The clinical presentation of elderly patients is often equivocal and requires broad differential diagnostic considerations. The ESC guidelines (2018) call for the appropriate choice of ischemia diagnostics (invasive versus noninvasive diagnostics) to determine the pretest probability for estimating relevant coronary stenosis. Age, sex, clinical presentation, and Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) staging of stable angina are considered (Table 1).

If the pretest probability is intermediate (15% to 85%, Table 1: yellow), noninvasive ischemia diagnostics should be performed primarily. If the pretest probability is high (>85%, Tab. 1: red) or if the typical pectanginal symptoms are very intense (CCS > III), an invasive workup by coronary angiography is recommended. The estimation of the pretest probability helps to avoid unnecessary invasive investigations, to justify necessary invasive investigations and to use resources more optimally, in addition to the appropriate choice of ischemia diagnostics.

The indication for coronary angiography should not be made lightly. However, withholding this can also lead to overlooking potentially treatable and life-threatening findings. Whether to ultimately seek revascularization should be based on prognostic and/or symptomatic factors. Invasive methods are constantly improving. Peri-interventional risk can be reduced and interventional options are steadily increasing. Consecutively, this leads to an increase in diagnostic and therapeutic coronary angiography. If the indication for coronary revascularization is not given, not wanted, or technically not possible, the aim is to achieve an optimal medical, anti-ischemic therapy. With this in mind, the elderly patient’s wish to have no more procedures can be accommodated and anti-ischemic therapy can alleviate symptoms. However, there are also many older patients who would rather undergo an intervention than have to take more medication. Ultimately, individual therapy is needed in close consultation with the patient [1,16].

What is the situation in the acute situation? In fact, elderly patients often present to the emergency department with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) or unstable angina and more rarely with ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Many of these patients are often treated rather reluctantly optimally with medication or invasively. Studies show that 80-year-old patients continue to benefit more from invasive interventions than from a drug-only strategy. In patients over 90 years of age, no difference was found between an invasive versus a medicinal procedure [21].

Valvular heart disease

The prevalence of valvular heart disease increases sharply with age. In our article, we will focus on aortic valve stenosis (AS) and mitral valve regurgitation (MI). Valvulopathies require a structured workup. In addition to a patient’s symptoms, the etiology, severity, and mechanism of a valvular condition must be understood and recorded. The pathophysiological effects, such as ventricular sizes, ejection fraction, or pulmonary arterial pressure, must be considered. The leading modality of examination is echocardiography. Extracardiac factors, concomitant diseases, general condition, and the patient’s will are central to the management of valvular heart disease and should be considered when establishing indications for the evaluation and treatment of valvular disease. If the indication for valve replacement is made, patients should be discussed preinterventionally by the cardiac team [3–5].

It is also important to note that the elderly cardiac patient is a peri- and postoperative specialty. Reduced mobility (objectified by 6-minute walk test) or oxygen dependence are considered major factors for increased postoperative mortality. Furthermore, there is a correlation between severity of renal insufficiency and mortality after valve interventions. Comorbidities such as coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, or peripheral arterial disease are negative predictors of survival. All these factors need to be analyzed by the treatment team [3–5].

Aortic valve stenosis

Conservative therapies, such as taking statins, cannot affect the progression of AS that is already moderately severe. Accordingly, asymptomatic patients with severe AS, or patients who do not yet qualify for valve replacement, should be monitored closely clinically and echocardiographically. For patients with severe asymptomatic AS, a six-month examination interval is recommended.

Surgical (aortic valve replacement, ACE) or catheter-based procedures (transcatheter aortic valve implantation, TAVI) are used as valve interventions. The choice of intervention method (AKE vs. TAVI) is in a state of great upheaval and requires interdisciplinary discussion within the Heart team. The 2017 guidelines are helpful in choosing the intervention method but are already out of date with the latest science. Aortic valve interventions should be performed only at centers with cardiology and cardiac surgery departments. The choice of intervention must be based on a careful and individualized evaluation.

Surgical aortic valve replacement is recommended in patients with a low surgical risk. In elderly patients, biological valve prostheses are implanted almost exclusively. The main advantages of this procedure are years of expertise and good long-term results.

TAVI is recommended in patients at increased surgical risk or in patients not suitable for surgical intervention. The main advantage for the patient is less invasiveness, but also rapid mobilization after the procedure. Studies have shown good results in low, intermediate, and high risk patients. Studies demonstrating long-term durability are lacking, although results up to 5 years look very promising. A lot is being invested in developments of new materials and techniques, and surgery is becoming safer and safer. The TAVI patient population will expand. In the future, it is likely that increasingly older/polymorbid patients and younger patients with low surgical risk will be able to benefit from TAVI [3–5,18].

Mitral valve regurgitation

Mitral valve regurgitation (MI) is the second most common indication for valve surgery. A primary and secondary MI are completely different, especially in terms of treatment (surgical vs catheter-based) [3–5].

Primary mitral regurgitation: In primary MI, one or more components of the mitral valve apparatus are directly affected. The most common causes are degenerative changes (prolapse, tendon filament rupture), followed by endocarditis. Valve surgery is the causal therapy for primary MI. Valve reconstruction should be preferred to valve replacement when possible. Age has no influence on the indication for surgery. Prescription of an ACE inhibitor and adequate heart failure therapy should be given to patients who do not yet qualify or do not qualify for surgery. The same applies in the case of persistent complaints, despite surgery having been performed. The management of severe chronic primary MI is outlined in the 2017 ESC guidelines [3–5].

Secondary mitral regurgitation: Secondary MI results from an imbalance between closing and holding forces on the mitral valve, as a consequence of a left ventricular geometry disorder. The most common etiology represents dilated and ischemic cardiopathy. Atrial fibrillation can also lead to dilatation of the left atrium and consecutive dilatation of the mitral valve annulus. Many of the elderly cardiac patients are affected by secondary MI.

Drug therapy is essential in secondary MI and is always the first step in treatment. This is based on the recommendations for optimal heart failure therapy. If symptoms persist despite optimal medical therapy, valve intervention should be evaluated. Structured assessment by the Heart Team is also desirable before mitral valve intervention. Ischemic cardiopathy represents a common reason for secondary MI. The blood flow situation resp. myocardial vitality is of central importance. If there is a revascularization option and the myocardium is considered vital, then mitral valve surgery should be discussed. If revascularization therapy is not necessary, the patient is receiving optimal medication, and the left ventricular ejection fraction >is 30%, surgery may be considered.

In addition to valve surgery, percutaneous procedures are increasingly used. For the so-called “edge-to-edge” procedure, also known as MitraClip, patients are suitable who do not require revascularization and the surgical risk is increased. In these cases, persistent symptoms are also a prerequisite despite optimal drug therapy and echocardiographically appropriate valve morphologies [3–5].

Atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is by far the most common cardiac arrhythmia. It is estimated that 25% of all current 40 year olds will develop AF during their lifetime. There is a direct correlation of AF prevalence with age. AF is associated with increased mortality and is responsible for 20-30% of all strokes. The prevalence of AF in patients over 65 years of age is approximately 5%; with 1.4% being undiagnosed [15]. The 2016 ESC guidelines recommend “opportunistic” screening in patients older than 65 years. Treatment should take into account different domains, which are exemplified by the elderly cardiology patient.

Predisposing factors: Cardiovascular disease increases the risk of AF, recurrent AF, or AF-associated complications. Hypertension, valvular heart disease, diabetes mellitus, obesity, pulmonary disease, and chronic kidney disease are often associated with AF [15]. Factors such as age, smoking, and excessive alcohol consumption are considered other predisposing factors. Lifestyle modification can reduce the frequency and length of AF episodes. be reduced [17].

Stroke prevention: to evaluate anticoagulation, the risk of stroke is determined by the CHA2DS2-VASc score. Age has a decisive influence here. Men with ≥2 points and women with ≥3 points benefit from anticoagulation. Individual bleeding risk and patient preference should be considered in deciding anticoagulation. Especially in old age, the risk of stroke should always be contrasted with the risk of bleeding. Various scores help to assess the risk of bleeding (including HAS- BLED score). The risk factors of stroke and bleeding overlap. Because of their more favorable side-effect profile and simpler administration options, DOAKs are usually preferred. If there is a clear contraindication to anticoagulation, especially in elderly polymorbid patients, left atrial appendage closure may be considered.

Regulation of heart rate: A distinction is made between frequency and rhythm control. In elderly patients, frequency control alone may well result in symptom freedom. Catheter ablation (pulmonary vein isolation) is an elegant method of symptom relief, especially when the patient is still very active. In an elderly patient who is no longer very active, frequency control is more likely to be used. If this fails with medication, AV node ablation and pacemaker implantation may also help [7].

Prevention of cardiovascular diseases

Increasingly, we are confronted with exciting discussions of primary and secondary prevention in older patients. Common risk assessments, such as the AGLA (Working Group on Lipids and Atherosclerosis) score for primary prevention of cardiovascular events, do not consider patients older than 75 years. Because of the paucity of data in elderly patients, there are only a few recommendations for primary prophylaxis in patients older than 75 years. A recently published study showed a potential cardiovascular risk reduction in 75-year-old patients who continued primary prophylactic statin therapy [10]. Statin termination in this age group resulted in more frequent hospitalizations for cardiovascular events. As a secondary prophylaxis, statin therapy is also indicated in the elderly [10]. Taking aspirin as primary prophylaxis, in healthy patients over 70 years of age, showed no advantage for disease-free survival over placebo. More deaths, mainly tumor-associated deaths, were registered in the aspirin group [14]. The importance of lifestyle modifications (balanced diet, physical activity) and co-treatment of comorbidities are central and independent of age.

Summary

In summary, there is no general answer to the question of whether maximal therapy is appropriate in an elderly patient. Basically, symptomatic therapy will be given at an older age. The prognostic aspects are less in the foreground. Criteria such as quality of life, open communication or social network are gaining importance in older patients. You can’t just focus on the “heart” organ. Holistic medicine and an interdisciplinary approach should be practiced. The individual consideration of the elderly patient becomes more and more important in order to provide him with the optimal, not always maximum therapy. Communication with the patient and the relatives plays a decisive role in this.

What are the needs and circumstances? Is the elderly cardiology patient still an active mountain walker, is his maximum radius the village store or even just the nursing home? In an active mountain walker, for example, pulmonary vein isolation will be evaluated even at an age over 75 years, whereas in a nursing home patient, atrial fibrillation will be treated primarily by frequency control. The situation is more difficult in cardiac emergencies. Should we hospitalize and revascularize a nursing home patient with an acute myocardial infarction? Here it is very important that these patients have already thought about and formulated their ideas together with their family doctor and their relatives. This is where a living will can help. This also applies to aortic valve stenosis, the indication for which is rarely sudden and surprising. If the patient and the primary care physician work out a possible treatment plan together at an early stage, the patient’s wishes can be addressed at the time of the valve replacement indication and the appropriate specialists (cardiology and cardiac surgery) can be consulted. Foresight can help provide optimal rather than maximum therapy.

Literature:

- Achenbach S, Naber C, Levenson B, et al: Indications for invasive coronary diagnostics and revascularization. The Cardiologist 2017; 11(4): 272-284.

- Balducci L, Bennett J. Anemia in the Elderly. Springer. 2007

- Baumgartner H, Cremer J, Eggebrecht H, et al: Commentary on the ESC/EACTS guidelines (2017) on the management of valvular heart disease. The Cardiologist, 2018; 12(3): 184-193.

- Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, et al: 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the Management of Valvular Heart Disease. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2017; 71(2): 110.

- Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, et al: (2017b). Pocket guideline: management of valvular heart disease (2017 version). European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and German Society of Cardiology (DGK).

- Despotovic D, Schmied CH: Increasing importance of cardiac biomarkers. info@heart+vessel, 2019; 2.

- Eckardt L, Deneke T, Diener HC, et al: Commentary on the 2016 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. The Cardiologist 2017; 11(3): 193-204.

- Emrich IE, Bohm M, Mahfoud F (2018): Pocket guideline: management of arterial hypertension (2018 version). European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and German Society of Cardiology (DGK).

- Emrich IE, Bohm M, Mahfoud F. The 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: A German point of view. Eur Heart J 2019; 40(23): 1830-1831.

- Giral P, Neumann A, Weill A, Coste J: Cardiovascular effect of discontinuing statins for primary prevention at the age of 75 years: a nationwide population-based cohort study in France. Eur Heart J 2019; 40(43): 3516-3525.

- Heart Foundation S. Figures and data on cardiovascular diseases in Switzerland. 2016 Edition. Swiss Heart Foundation.

- Jia L, Zhang W, Chen X: Common methods of biological age estimation. Clin Interv Aging 2017; 12: 759-772.

- Mahfoud F, Böhm M, Bongarth CM, et al: Commentary on the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Society of Hypertension (ESH) guidelines (2018) for the management of arterial hypertension. The Cardiologist 2019; 13(1): 17-23.

- McNeil JJ, Nelson MR, Woods RL, et al: Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med 2018; 379(16): 1519-1528.

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al: Heart disease and stroke statistics–2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015; 131(4): e29-322.

- Neumann FJ, Byrne RA, Sibbing D, et al: Commentary on the ESC and EACTS guidelines (2018) on myocardial revascularization. The Cardiologist 2019; 13(4): 181-192.

- Pathak RK, Middeldorp ME, Lau DH, et al: Aggressive risk factor reduction study for atrial fibrillation and implications for the outcome of ablation: the ARREST-AF cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64(21): 2222-2231.

- Siontis GC, Praz F, Pilgrim T, et al: Transcatheter aortic valve implantation vs. surgical aortic valve replacement for treatment of severe aortic stenosis: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur Heart J 2016; 37(47): 3503-3512.

- Statistics, B. f. (2017). Health Care Section, Population Health. Pocket statistics 2017.

- Statistics, B. f. (2018). Permanent resident population by citizenship category, age and canton, 3rd quarter 2018.

- Tegn N, Abdelnoor M, Aaberge L, et al: Invasive versus conservative strategy in patients aged 80 years or older with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction or unstable angina pectoris (After Eighty study): an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 387(10023): 1057-1065.

CARDIOVASC 2019; 18(6): 26-29